Executive Summary

Over the past several years, the rise of the Federal estate tax exemption has dramatically reduced the scope of “traditional” estate planning, which is less about estate tax planning now and more about simply ensuring that the right legal documents are in place to specify how various assets should be disposed of, and who is responsible for doing so.

Yet at the same time, the rise of the digital world has created a new wrinkle for estate planning: how to transition “digital” assets. Which is important not only for those digital assets that can carry a monetary value (such as cryptocurrencies, domains, websites, etc.), or login credentials to such sites (e.g., usernames and passwords to bank and investment accounts), but also social media profiles and actual media files (e.g., digital photos). As once the account owner passes away (or is merely incapacitated), the heirs may have difficulty finding and accessing those digital assets after the fact.

While it might seem simple enough to solve the problem by just keeping a list of account credentials “in a safe place” for someone to use “just in case”, the fact that they might have the information to access to the accounts doesn’t necessarily mean that they have the legal authority to do so, especially when a website’s Terms of Service do not permit a transfer of ownership. In fact, heirs could potentially be found guilty of “hacking” by trying to access a loved one’s online accounts after he/she is gone… even if it was the individual’s dying (but not legally binding) wish!

To address the situation, various legal measures have been proposed in recent years, including the Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act (UFADAA), and the Privacy Expectation Afterlife and Choices (PEAC) Act. But after various implementation struggles, the Uniform Law Commission ultimately created the Revised Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act (RUFADAA) in 2015, which received widespread support and in just a few years has been adopted by more than 40 states.

RUFADAA gives a clear hierarchy of instructions for how a person’s digital assets are to be treated should a fiduciary seek access, which may include not only executors after death, but trustees, court-appointed guardians, and attorneys-in-fact. The starting point is that online service providers can create an “online tool” that functions as a form of “digital power of attorney” to specify who has control and access for that specific site. In addition, RUFADAA provides a clear legal framework for digital asset rights to be specified in traditional legal documents (e.g., Wills and powers of attorney). And clarifies that it’s only in the absence of an online tool, or any legal documents, that finally the service provider’s own Terms of Service will control.

Ultimately, the importance of estate planning has always been about ensuring that assets are distributed in the desired manner after death, and identifying the individual(s) responsible for doing so. But the complications of digital estate planning are unique, not only because of the complexities of bequeathing “digital” assets, but also because most individuals accumulate so many online accounts it may be difficult to even know where all the digital assets are! Fortunately, though, that means there’s a valuable role for the financial advisor to play in helping clients to ensure their digital estate plan is in order. Starting with helping clients at the next meeting understand the value of using a secure password manager, not only for the benefits of cybersecurity, but because it can form the core of the digital asset inventory they’ll want to begin the digital estate planning process!

What Is Digital Estate Planning?

When you say the words “estate planning”, the image that comes to mind for many is of the ultra-wealthy planning to avoid federal estate tax on the transfer of their assets. To others, it’s simply a matter of transferring whatever they have in financial assets and personal property to the next generation as efficiently as possible. Others may incorporate end of life planning, such as living wills and health care proxies into the mix. The reality though, is that estate planning in the modern age entails much more than all of these.

Traditionally, estate planning has addressed tangible personal property, real property, and intangible property with financial value, such as a bank or brokerage account. People today, however, often have purely digital assets as well, and those assets don’t necessarily fit the traditional categories, necessitating a form of “digital estate planning” to address such situations.

In fact, it can sometimes be challenging to figure out where traditional estate planning ends, and where digital estate planning begins.

Suppose, for instance, that you take a picture with one of those old Polaroid cameras that spit out the picture after it was taken! After 30-60 seconds of shaking and waiting for the chemical reaction to do its thing, voila! A printed picture!

Here, both the camera, and the picture itself, are tangible personal property… the type of stuff generally covered by traditional estate planning. If you had a Will that left all of your tangible personal property to your child, both the camera and the print of the picture would belong to your child.

But what if you took the picture with a digital camera, or a phone, and stored the image on a hard drive? If you bequeath your tangible personal property – which would include the hard drive – does your bequest also include all the files (e.g., the digital picture) on the hard drive stored in zeros and ones?

How about if the photo is stored online in the cloud, or to a social media site? Now you don’t even own the hard drive. But you may still own the rights to the digital picture stored there?

As you can see, sometimes the line between digital asset and non-digital asset can be a bit blurry. A useful analogy here is a file cabinet stuffed with files. You might choose to leave the file cabinet to your child, but the files within the cabinet to your business partner. Simply put, the contents and the container are not the same. And the same can be true of computers and the digital files stored on them – whether your own, or in the cloud.

Continuing with our analogy, digital estate planning is concerned with how the files within the cabinet are transferred, without regard for the cabinet itself. More generally, it is the process of cataloging, organizing and planning for the disposition of one’s digital assets after death.

Of course, all of this still begs the question of what, exactly, are “digital assets”, and where do you draw the line in the first place?

What Are Digital Assets?

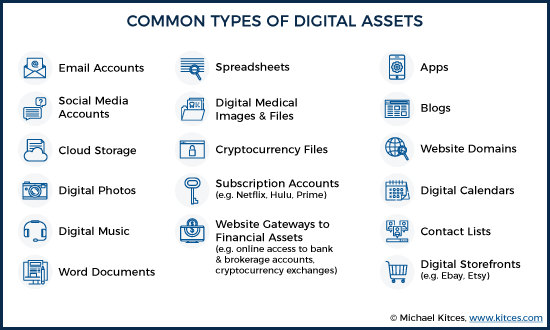

When in doubt, try to think of digital assets as anything that’s stored in electronic form (but separate from the physical hardware on which that electronic data lives). Digital assets can be just about anything and everything that is created, communicated, sent, received, or stored by electronic means.

In practice, though, digital assets are more than just “files” stored on a computer. Some digital assets have intrinsic financial value (such as cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin, Dash, Ripple, XRP, EOS, Stellar, and Monero), as well as popular digital storefronts (e.g., a popular and highly rated eBay Seller’s page), and valuable domain names.

In other cases, digital assets may have no such financial value in and of themselves, but are gateways to accessing assets with financial value, such as the credentials to log into online banking or brokerage accounts. Increasingly digital assets also include massive amounts of nonfinancial information as well. Such assets include email accounts, contact lists, social media accounts, pictures (as described above), videos, purchased digital music and movies, and other information that has been stored in a digital format.

Digital Asset Rights And Legal Challenges In Transferring Control

From the beginning of the “information age”, and up until only a few years ago, access to digital assets by anyone other than the owner of those digital assets – typically the user of some online service or website – was governed almost exclusively by the service/website’s Terms-of-Service (ToS) agreement, rather than by property law.

This created a number of issues upon the death of the owner of those assets, or in the event the owner was otherwise incapacitated and unable to effectively manage their own affairs. Because suddenly, heirs may have no way to log into the now-incapacitated-or-deceased owner’s account to access those photos, emails, or other digital assets. And the account providers (e.g., various cloud storage or social media sites) are under no legal obligation to let others access a deceased or incapacitated individual’s accounts.

In practice, many people simply dealt with this by saying “Well, I’ll just write down a list of all my usernames and passwords, and give them to a trusted confident.”

However, this is not an effective and legal way to handle the situation. In fact, when a third-party user accesses someone else’s account without being an authorized user – even because that original owner handed them the login credentials – it is technically an act of “hacking”. The word “hacking” may sound nefarious and conjure up images of faceless men and women in hoodies hovering over keyboards, but the reality is that anyone who knowingly accesses a computer or account without proper authorization is hacking. And hacking is potentially punishable by law under a variety of statutes, including the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, and the Electronic Communications Privacy Act.

In other words, simply giving someone access to a username and password is not nearly sufficient to grant them the legal authority to access that information when a Terms-of-Service agreement does not allow for such transfers of rights (and most don’t). Simply put, the website does not have to allow or honor that person’s access to the account, and remains well within their rights to simply say “This account was created specifically for the owner, and the owner died, so this account is being terminated, and its contents will now be deleted.” The heirs don’t have any legal right to preserve the account and its digital assets just because they have the login credentials.

In reality, this problem is not all that dissimilar from situations in the “real world”. Suppose, for instance, that you’re going to be out of town on an extended vacation, and are worried about paying bills while you’re away. So you reach out to a trusted friend, give them your checkbook, and ask them to pay any bills that come in while you’re away. Without proper legal authority, if that friend signs your name to one of those checks, it could land them in substantial trouble with the law. They are not legally your attorney-in-fact, which makes writing checks in your name an act of fraud. The same concept applies to accessing digital assets without the appropriate legal authority.

Yet with more and more of our lives going digital, the situation needed to be addressed – across a rapidly growing range of different websites and online services that might constitute or hold someone’s digital assets. Absent getting every service associated with a digital asset to change its Terms-of-Service agreement to allow for executors and other fiduciaries to access a user’s digital assets – a Herculean task at best – the only potential solution was legislative action to create a uniform legal standard to handle such situations.

Standardizing Digital Asset Rights With UFADAA And The PEAC Act

The first significant attempt to create a framework that would more thoroughly deal with the legal rights for digital assets (especially in the estate planning context) was the Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act, or UFADAA (typically pronounced yoo fä’ dä - like someone from Brooklyn, NY talking about someone else’s dad – “Hey I know yoo fä dä!”) for short.

UFADAA, which was approved by the Uniform Law Commission on July 16, 2014, sought to give various rights with respect to digital assets, such as access and control, to potential fiduciaries who might need those rights to execute their duties, such as executors, guardians, trustees, and powers of attorney. In essence, the primary purpose of UFADAA was to put these fiduciaries’ powers in the digital world on par with their powers in the physical one.

Notably, though, the Uniform Law Commission is a state-supported organization that seeks to “provide states with non-partisan, well-conceived and well-drafted legislation that brings clarity and stability to critical areas of state statutory law.” In short, the Commission takes up matters of importance, and drafts model laws that states can then choose to adopt… or not.

A key point to understand is that while the Commission does draft model legislation, it has no power to enact the legislation. Thus, while the Commission has helped to draft model legislation that has been almost universally adopted by states (i.e. the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), the Uniform Probate code, and the Uniform Transfers to Minors Act (UTMA)), it cannot force any individual state, or group of states, to adopt the model law as actual law. Rather, each state, under its Constitutionally afforded powers, is given the authority to choose what legislation to adopt, and whether to make any changes to Commission’s model law; meaning that even “uniform” laws are not necessarily identical (though they’re generally pretty close) from state to state).

Fortunately, soon after the UFADAA was approved, Delaware become the first state to enact a version of the law, and by the end of 2015, roughly half of all state legislators had at least introduced a version of the act. It seemed that widespread adoption was inevitable.

Except it wasn’t... so much so, in fact, that Delaware was not only the first state to adopt UFADAA, but also the last (i.e., the only) state to do so!

What happened? Why the sudden reversal of course? Two words: “Big business”. Companies like Google and Facebook were none too pleased with UFADAA.

They argued, amongst other things, that the powers given to fiduciaries under the law were far too broad (executors, for instance, were granted default access to a decedent’s digital assets, and only if the owner had affirmatively opted out of such treatment while they were alive were those rights restricted). This worried companies, like Facebook and Google, who were worried that determining who should, and should not, be granted access to a decedent’s account would be an undue burden on them, creating substantial business complications and potential legal liability (if they ended out giving access to the “wrong” person). They also argued that UFADAA was at odds with certain existing legislation, such as the Stored Communications Act.

In the end, state legislatures buckled under massive pressure from lobbyists, and UFADAA was stopped cold in its tracks.

The big tech companies didn’t just stop talking about the issue once UFADAA was put on hold. It was still clear that some sort of legal framework was needed to address the growing concerns surrounding fiduciaries’ access to digital assets. So in an effort to steer the conversation in a different way, big tech companies drove the creation of their own legal framework, the Privacy Expectation Afterlife and Choices (PEAC) Act.

Unlike UFADAA, though, the PEAC Act only addressed an executor’s rights (but not attorneys-in-fact, guardians, and others who might potentially need or be granted access). Furthermore, as you might expect, it took an extremely narrow view of when an executor could legally access a decedent’s digital assets (which the companies did to protect themselves and reduce potential responsibilities). A court order was always required, and even then, the executor would often be limited to only specific records (e.g., one year’s worth of records), and in some situations, the tech companies could actually override the court order and still refuse to share certain information. Clearly, this wasn’t going to be a workable framework either, and not surprisingly, few state legislatures even moved to introduce the law.

RUFADAA As A Compromise For Digital Assets Rights

In response to the concerns raised by the big tech companies, and the non-starter that was the PEAC Act, the Uniform Law Commission went back to the drawing board and, on July 15, 2015 – almost a year to the day after approving the UFADAA – it approved the Revised Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act, or RUFADAA.

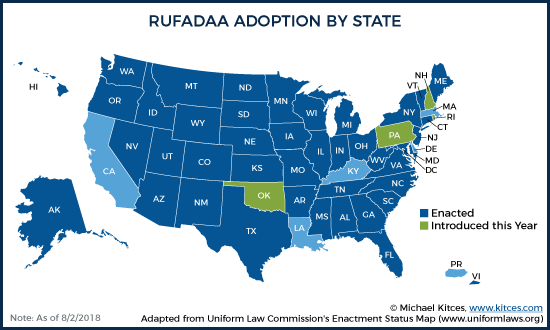

Unlike the first version of the legislation, this iteration received widespread support, picking up key endorsements from consumer advocate groups such as AARP and the National Academy of Elder Law Attorneys, as well as from big tech companies (e.g., Facebook and Google) which had so feverishly opposed the original version of the Act.

With such broad support, and a desperate need to address a growing problem, it should come as no surprise that states have been quick to adopt RUFADAA. Since the Uniform Law Commission’s formal approval of the Act in July of 2015, nearly 40 states have adopted the RUFADAA, and another five jurisdictions have introduced the bill into their state legislatures this year. Thus, fiduciary access to most clients’ digital assets is already, or will soon be, controlled by RUFADAA.

THE RUFADAA’s Basic Legal Framework For Digital Assets

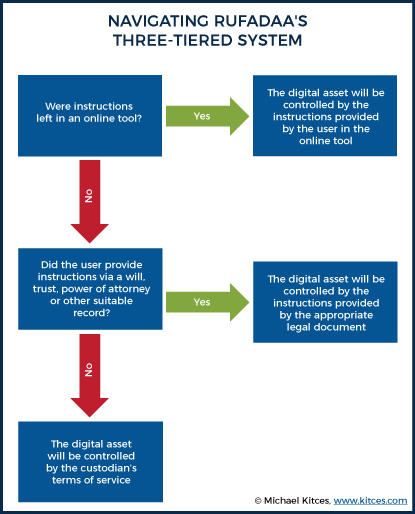

One of the key advantages of RUFADAA over the PEAC Act is that it provides a framework for not just executors, but also for most other common fiduciaries, such as trustees, agents appointed under powers of attorney, court-appointed guardians, and conservators of protected persons’ estates. The Act also creates a clear hierarchy of instructions – a so-called “three-tiered system of priorities” – that provides a clear path as to how a person’s digital assets should be treated in the event a fiduciary seeks access from a service provider (referred to in the act as “custodians”).

RUFADAA Tier One – “Online Tools”

Under RUFADAA, any instructions provided by a user in a custodian’s “online tool” for how the account should be handled after death or incapacitation – for instance, via Google’s “Inactive Account Manager” or Facebook’s “Legacy Contact” – will have priority over any and all other instructions, including Terms of Service (as long as that online tool can still be modified or deleted at any time). In this context, RUFADAA defines an online tool broadly as “an electronic service provided by a custodian that allows the user, in an agreement distinct from the terms-of-service agreement between the custodian and user, to provide directions for disclosure or nondisclosure of digital assets to a third person.”

In essence, RUFADAA granted these online tools a power roughly akin to a digital power-of-attorney, applicable to the specific service provider/custodian offering the tool.

Accordingly, Google’s Inactive Account Manager allows Google users to notify a “trusted contact”, and if desired, to share information with that contact, once an account has been inactive for a certain amount of time. Users can also instruct Google to delete certain information.

Similarly, Facebook’s Legacy Contact allows users to name someone to “look after” their account after they’ve passed away (alternatively, users can request that their accounts be permanently deleted). While Legacy Contacts are not given full access to a user’s account, and are prohibited from activities such as reading messages and removing or changing past posts, they are able to do things, such as writing a pinned post for a profile, updating profile pictures and cover photos, and requesting the removal of a user’s account.

It’s important to note that under RUFADAA, though, when an individual opts to use a custodian’s online tool, they are rendering all other instructions irrelevant. Which means it overrides not only the provider’s default Terms of Service, but also the client’s own Will, trust, power of attorney, or other legal document that might name a person to oversee their digital asset(s). Thus, even if the client has named an executor or attorney-in-fact, if that person is different from the person they instructed the custodian to share information with, via an online tool, the individual named in the online tool will be granted access, and the individual named in the legal document will not be granted access.

Thus far, these online tools to denote post-death control and similar arrangements are still in their infancy, but it is reasonable to think that many more custodians of digital assets will incorporate such tools into their platforms in the coming years. As people continue to create, transmit, and store more information online, it will become increasingly important for them to ensure a smooth transition of those digital assets to others at the relevant time. Thus, custodians are likely to increase adopt such tools as a way of enhancing the user experience.

An even greater incentive for custodians to create and use online tools, however, is that it is a much more efficient way for them to deal with the transfer of, and/or access to, users’ information upon their deaths or other life events. If a custodian can get its user to engage its online tool as a way of telling the custodian to whom access to digital assets should be granted, to which assets they should be granted access, and which rights they should be granted for those assets, those custodians can streamline the process, increasing efficiency and better managing their costs if/when/as accounts need to be transition. Otherwise, custodians would be weighed down in the time and cost of slogging through their users’ legal documents to figure out who to grant access to… which brings us to tier two of RUFADAA.

RUFADAA Tier Two – Legal Documents

In the event that a custodian does not offer an online tool, or if a user does not opt to use an available tool, then RUFADAA will look to the users’ legal documents, such as a will, trust, or power of attorney. Such documents can be used to explicitly grant a fiduciary access to any/all digital access, or to restrict such access. Which is important, because prior to the development of RUFADAA – and still often the case in states where RUFADAA has not yet been adopted – these documents were largely ignored by custodians (who feared that they might be held liable if it turned out the documents weren’t up to date and they acted on outdated instructions).

RUFADAA also addresses certain rights an executor may have to a decedent’s digital assets, even if the decedent’s legal documents do not specifically address such matters. For instance, RUFADAA specifies that as long as a decedent does not leave any instructions to the contrary, via either an online tool or a legal document, a custodian must provide an executor with a “catalogue” of a user’s communications, if such information is requested.

Catalogues include to/from whom a message has been sent/received, the time and date of the communication, and the corresponding electronic address. A catalogue does not, however, include the actual content of any communications (for which a user would still have to affirmatively grant access via an online tool or a legal document). Therefore, if individuals wish to keep private even the more limited information available via a catalogue, they should be sure to leave explicit instructions in a Will or other legal document indicating such a desire to limit access, as it’s not enough for the documents to merely be silent on matters regarding digital assets to limit access.

Tier Three – Terms-of-Service Agreements

In the event that a user provides no instructions via an online tool nor via legal documents, then the custodian’s default Terms of Service will dictate a fiduciary’s access to a user’s digital assets.

In the event that a user provides no instructions via an online tool nor via legal documents, then the custodian’s default Terms of Service will dictate a fiduciary’s access to a user’s digital assets.

While this isn’t necessarily problematic, the reality is that most users don’t read much, if any, of the (commonly dense legalese) Terms before scrolling through to find the “Accept” button. Which means that, over the years, users may have agreed to just about anything without even knowing or realizing what they were agreeing to at the time!

Indeed, the long-running animated show, South Park, famously addressed this matter in back in 2011, in its now-infamous HumancentiPad episode. The episode imagined a scenario where agreeing to Apple’s iTunes Terms-of-Service agreement would allow the company to sew… well, let’s just say it gave Apple a little too much power. (If you want to know the details, you’ll have to Google it or watch the episode for yourself, but be forewarned, it’s not for those with a weak stomach.)

While most Terms-of-Service agreements are fortunately more benign than the HumancentiPad example, the challenge is still that many custodians’ Terms of Service are written in manner that minimizes their responsibility after the primary user dies, sometimes to the frustration of heirs. For instance, Oath’s Terms of Service (Oath is the name of the Yahoo!-AOL combination owned by Verizon) dictate that most accounts terminate upon the user’s death.

“With the exception of AOL accounts, all Oath accounts are non-transferable, and any rights to them terminate upon the account holder’s death.”

The premature termination of a user’s account can result in a number of complications, both financial and non-financial. On the financial side of things, many people receive a host of bills online, via email. Knowing what a decedent’s outstanding bills are is a critical piece of information for an executor, who is, in part, charged with satisfying a decedent’s outstanding debts. And in today’s modern society, it’s entirely conceivable that there is no record of these accounts/expenses in the physical world! Thus, the deletion of a user’s account could lead to an increase in the likelihood of bills not being paid in a timely manner after death, leading to potential penalties or other unwanted results.

Non-financial issues can be just as problematic, if not more so, when an account is terminated “promptly” at the users death. A lifetime’s worth of pictures, for instance, may be stored in a cloud service, or similar provider, and suddenly be permanently lost when the account is deleted. Contact lists of friends, family and coworkers – the people whom you would want notify of the decedent’s passing – may be lost and unable to be replicated elsewhere.

The list of potential problems goes on and on, which is why taking the time to properly plan one’s estate, both in the physical world and the digital world, is so important.

The Financial Advisor’s Role In Digital Estate Planning

When it comes to planning for digital assets, financial advisors are likely in one the best positions – if not the best position – to help clients get their digital estate planning in order. Of course, as with traditional estate planning, a lawyer is still needed to provide formal legal advice and/or the complete the drafting of legal documents. Nonetheless, as with traditional estate planning, there is still an important role for financial advisors to play, to ensure that the client’s house (or digital house) is in good order and that the estate planning documents will actually play out as intended!

Help Clients Create A (Digital) Inventory Of (Digital) Assets

One of the most important roles a financial advisor can play in the digital estate planning process is to help clients to develop an accurate inventory of digital assets. Because a key challenge in digital estate planning – even more so than with planning for traditional assets – is that clients themselves may not to be aware of all their digital assets… or at least to be unable to sufficiently recall them all to compile a complete inventory. Think about how many online websites there are to which you currently have access… could you recall them all immediately? Chances are the answer is no. In fact, a recently released report from password management tool LastPass indicated that the average employee using its tool was managing 191 passwords. That number probably isn’t going to be going down anytime soon either. According to DashLane, another password management tool, the number of online accounts we use is rising at a rate of roughly 14% per year!

To try and counter this problem, advisors should not only work with clients to create an inventory of accounts, but consider encouraging clients to use a password management tool, such as Dashlane, Sticky Password, LastPass, Keeper, or Password Boss as well.

Note: While it’s good to help clients create their digital inventory, advisors must be careful to avoid actually taking possession of clients’ usernames and passwords to bank, brokerage, and other financial websites, in order to avoid inadvertent custody of client assets.

For clients resistant to the use of such tools, alternative measures, such as compiling a physical (i.e., handwritten) list of digital assets over time – to be stored in a safe location like a fireproof safe or a safety deposit box – can work. If clients choose to create an electronic inventory – e.g., a Word document that lists out all their usernames and passwords – advisors should encourage clients to make sure all usernames and passwords stored in digital format are encrypted (and when possible, use additional security measures such as multi-factor authentication).

It’s also important to remember that digital assets aren’t just accounts with logins and passwords. Be certain to include digital assets that don’t have a username and/or password on the inventory list as well, such pictures stored on a portable hard drives.

Updating The Estate Plan To Consider Digital Assets

Once the inventory of digital assets has been compiled, advisors should inquire about what a client would like to happen with the various digital assets after the client has passed, whom they would like to be responsible for seeing their wishes fulfilled, and what steps (if any) the client has already taken with respect to their digital estate plan. Of particular importance would be understanding if they have already made use of any online tools, since any instructions provided via one of those tools would override any other planning actions taken.

Once a client’s wishes (and current plans) with respect to their digital assets are known, it’s time to identify what gaps may exist in the current (digital) estate plan that need to be addressed with an estate planning attorney.

In analyzing the situation, it’s important to understand the rules surrounding digital assets for the state in which the client lives. Advisors comfortable doing so may wish to check whether the state has adopted RUFADAA (you can find an up-to-date list of states which have adopted the framework here), and if so, whether there have been any major departures from the model framework created by the Uniform Law Commission (such as a material change in the three-tiered structure).

Obviously, each client’s situation is unique and needs to be evaluated based on the specific set of facts and circumstances. Nevertheless, there are some recommendations that will likely apply to a broad section of clients. These include:

- Recommending the client consult with a qualified attorney, who can update legal documents to not only include instructions related to digital assets, but identify the relevant individuals authorized to act. Some clients may wish to use their legal document(s) to explicitly appoint a special “digital fiduciary”, separate and apart from the executor/fiduciary in charge of other financial or estate matters. Similarly, clients may choose to name multiple digital fiduciaries within a single legal document, each entrusted with the authority for different legal assets. This may be useful in a variety of situations, such as when:

- Fiduciaries themselves may have different levels of expertise/comfort with different digital assets. For instance, an individual may feel that one fiduciary is sufficiently capable of handling online bank and brokerage accounts, but feels another fiduciary would be better to manage their social media accounts. Or perhaps a special fiduciary is needed to handle uniquely complex digital assets, such as liquidating, or transferring to heirs, cryptocurrency held in cold storage.

- An individual may wish to keep certain matters private from their “regular” fiduciary. For instance, spouses, children, or close family members/friends are typically named as an executor, power of attorney, or other fiduciary, but there may be certain digital assets the individual wishes to be kept private from those individuals. Parents, for example, may not want children to have access to every text, email or other message sent between their parents. Indeed, in some instances, spouses themselves may not want one another to have access to all their digital content.

- Suggesting the use of a password manager, such as Dashlane, Sticky Password, LastPass, Keeper, or Password Boss. Given the amount of sensitive information stored by such a service, it is always best to make use of all available security features, including multi-factor authentication.

- Using specialized services designed to assist in the digital estate planning process. In recent years, several companies have sought to fill some of the gaps in the digital estate planning space. Such companies include Estate Map and My Wonderful Life, which was featured on ABC’s Shark Tank several years ago (they didn’t get a deal). Advisors wishing to help clients with such matters more directly may wish to consider one of the many industry-specific tools that have begun to emerge, such as Everplans, Yourefolio, or Legacy Shield.

Make Digital Estate Planning Part Of The (Next) Client Review Meeting

Clearly, building the digital asset inventory and implementing a sound digital estate plan is not something that’s going to happen overnight for most people. To that end, unless there are health issues or other factors that would make accelerating the digital estate planning process more important, advisors may wish to implement this process over several regularly scheduled update/review meetings with clients.

For instance, during your next review meeting with each client, bring up the idea of digital estate planning, and introduce the concept of a password manager. Over the next three to four months – or whatever your normal meeting cadence is – let the client use the password manager to build up their list of digital assets.

Then, at the next meeting, begin to discuss what the client would like to see happen with each of those various assets, whether there are any special websites/accounts involved (e.g., where all their photos and memories are stored, or a particularly valuable business), and perhaps, begin to discuss potential issues and strategies, such as updating the legal documents to ensure those digital assets are handled by the right person and are bequeathed to the right people.

Of course, once recommendations are made, and a client has decided to move forward, it’s incumbent upon the advisor to follow-up to ensure the plan is actually put into action. Too often, without an external nudge, the digital estate plan (like many traditional estate plans) will “die on the vine.”

And just as a financial plans should be updated and reviewed on a regular basis, so too should digital estate plans. Technology continues to progress at lightning speed, and a client’s digital asset inventory may change substantially over the course of even just a few years. Fortunately, the use of a password manager tends to keep an ongoing inventory up to date, but special accounts, digital assets, and website domains should still be reviewed and discussed, and digital estate plan updates are especially important for those who may not keep a timely updated inventory. Plus, there are “regular” planning considerations that may necessitate revisions of the plan, such as the death of a previously named executor, or a change in law.

Final Thoughts

In recent years, many advisors have sought to expand their services in an effort to retain clients and justify their fees, in an era where investment management has become increasingly commoditized. While digital estate planning may not currently be among many advisors’ strongest skills, its growing importance in today’s high-tech, increasingly-digital world, makes it an excellent way to add the additional value to the client experience so many advisors seek.

Awesome article. DIdn’t realize sharing accounts/passwords could be against the law.

http://www.clocr.com is a new entrant in the digital asset management space.

The blog is very useful. The information provide in the blog is important for all. Thank you for sharing this informative blog.

Ethiopian Embassy Consular