Executive Summary

Traditionally, a registered investment adviser is in the business of providing investment advice to others, while a registered investment company – such as a mutual fund – exists primarily to invest in securities, often by pooling together the collective dollars of multiple investors.

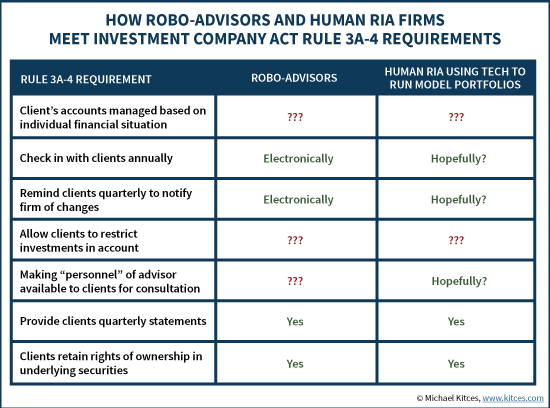

Yet as technology makes it increasingly feasible for investment advisers to operate “efficiently” by formulating standardized model portfolios and implementing them uniformly for all clients, the question arises of where to draw the line between where investment advice ends and an (unregistered) investment company begins.

Rule 3a-4 of the Investment Company Act attempts to draw the line by stipulating that an investment adviser is “safe” from being deemed an investment company, as long as its portfolios are customized to individual clients, and the firm provides access to “personnel” of the advisory firm who are knowledgeable about the client’s account and how it is being managed.

Yet given the standardized investment portfolios of today’s robo-advisors, and the fact that most proudly state that they do not layer in the cost of a human advisor, the question arises of whether many of today’s robo-advisors even qualify for the Rule 3a-4 exception, or whether they really are operating as unregistered investment companies!

Notably, though, the issue is actually not unique to robo-advisors. The growing frequency of human (investment) advisers utilizing model portfolios and technology to implement them means some human-based RIAs may be running afoul of Rule 3a-4 as well. And if they’re not, ironically the shift of human advisors beginning to offer “robo” solutions to their clients could actually exacerbate the problem, if firms actually do so by eliminating direct human interaction with their clients!

What’s The Difference Between An Investment Company And A (Registered) Investment Adviser?

The SEC differentiates between an investment company and an investment adviser by noting that advisers are in the business of providing investment advice to others, while an investment company is primarily engaged in the business of investing in securities themselves.

Of course, in practice many registered investment advisers also invest in securities (i.e., stocks and bonds) as a part of providing discretionary investment management services to clients. However, in this context an investment adviser is separated from an investment company because investment companies typically pool their investor dollars together and manage on a collective basis, while investment advisers manage each client’s account separately and in a manner that is personalized to the individual client.

For much of the history of investment advisers and investment companies (which date back to the Investment Adviser Act of 1940 and the Investment Company Act of 1940), these differences were sufficient to distinguish between the two. Investment advisers provided personalized investment advice and invested each client’s account uniquely in accordance with his/her investment needs, while investment companies pooled investor dollars together (e.g., in an open-ended mutual fund, a closed-end fund, or a unit investment trust) and managed standardized portfolios that by definition were the same for every investor who held a pro-rata share.

The Rise Of Discretionary Managed Accounts With Model Portfolios

The separation of investment companies from registered investment advisers was relatively clear for the first several decades, but the SEC became concerned when in the late 1960s, investment advisers began to offer standardized managed accounts (e.g., using model portfolios), where all clients that chose a particular model would be invested in an identical manner.

In the SEC’s view, when all clients have assets managed in a similar manner, and not necessarily customized to the individual needs of each client, the adviser is no longer “just” an investment adviser but is operating a de facto investment company, and should register as such. The matter was particularly concerning for the SEC in the case of investment advisers who managed a large volume of small accounts in an identically-modeled managed account, where it was unclear whether or how the investment adviser could possibly really be providing individualized and personalized investment advice on a systematic basis.

To address the issue, the SEC proposed a new Investment Company Act Rule 3a-4 in 1980 (Investment Company Act Release No. 11391), which would have clarified that investment advisers are not an investment company as long as they provide continuous personalized investment advice, and that clients maintain individual ownership of their all their investment holdings in their own accounts (unlike with a mutual fund, where the mutual fund has most of the substantive rights of investment ownership, from receiving information about the investments to voting shareholder proxies).

The original 1980 proposed rule was controversial and the SEC did not move forward, but it was re-proposed in 1995 after an SEC enforcement action against Clarke Lanzen Skalla resurfaced the issue (Skalla had a mutual fund asset allocation program where the standardized asset allocation models themselves were deemed to be an unregistered investment company). Based on additional experiences the SEC had during the intervening years (including several investment advisers who requested “no-action” letters to affirm that their planned activities would not run afoul of the investment company rules), and after gathering additional feedback from commentators, the SEC ultimately enacted Investment Company Act Rule 3a-4 in 1997.

Rule 3a-4 Of The Investment Company Act – When Investment Advisers Are NOT An Investment Company

The final version of Rule 3a-4 (which remains in force today as enforced by the SEC) stipulates that an investment adviser with discretionary management and using model portfolios has a “safe harbor” from being treated as an (unregistered) investment company as long as:

1) Each client’s account is managed on the basis of the client’s individual financial situation and investment objectives, which should be gathered upon opening the account

2) At least annually, the investment adviser contacts the client to proactively try to determine if there have been any changes to the financial situation or investment objectives

3) At least quarterly, the investment adviser notifies the client in writing reminding the client to contact the firm if there are any changes to the financial situation or investment objectives

4) Clients have the ability to impose reasonable restrictions on how the account is managed, including specifying particular securities or types of securities that should not be purchased

5) Some personnel of the investment adviser, who are knowledgeable about the account and its management, are reasonably available to the client for consultation

6) Clients receive at least quarterly a statement of all activity in the account (including transactions made, contributions and withdrawals pertaining to the account, fees and expenses charged to the account, and beginning and ending values)

7) Clients retain all rights of ownership in the underlying securities, including the right to engage in shareholder votes for securities in the account, to sue a security issuer (without being required to proceed jointly with other shareholders), to receive notification of trade confirmations and related documentation, and withdraw funds at any time.

In this context, the first five requirements are primarily meant to ensure that investors continued to receive individualized investment advice and guidance (even if held in a ‘standardized’ model portfolio in a discretionary managed account) on an ongoing and continuous basis. The 6th and 7th requirements are meant to distinguish a managed account from a pooled investment company, where investors in an investment company generally do not have access to the details of underlying securities transactions and may cede their other rights in the securities they own (e.g., allowing the mutual fund to vote securities by proxy).

Are Robo-Advisors A Registered Investment Adviser, Or An Unregistered Investment Company?

The reason this distinction between an investment adviser and an investment company using model portfolios for a large volume of small accounts is important in today’s environment, is that it’s not entirely clear whether robo-advisors should properly be classified as investment advisers or an (unregistered) investment company.

The issue was first raised last year by Melanie Fein, an attorney who wrote a white paper detailing how robo-advisors may not actually satisfy the requirements to be registered investment advisers. And while the research was commissioned by asset manager (and potential robo-advisor competitor) Federated Investors, it nonetheless raises valid questions about whether robo-advisors truly meet the safe harbor requirements to avoid being investment companies.

For instance, Rule 3a-4 requires that clients be able to impose restrictions on the account to exclude certain securities or types of securities. Yet it’s not clear that many (or any?) robo-advisor platforms are configured to allow an investor to exclude a particular security that is otherwise used in its models. For instance, what if an investor requested to not use Vanguard funds for their particular ETF choices (or Schwab’s ETFs, or some other provider)? What if an investor asked for high-yield bonds, or international equities, or some other asset class to be excluded? Notably, a robo-advisor hypothetically could create an option for investors to request the exclusion of certain securities, but until the platforms actually do, they may be in violation of the safe harbor and operating as “unregistered investment companies”.

Another issue with the ability of robo-advisors to satisfy Rule 3a-4 is regarding the requirement to gather information about the investor’s financial situation and investment objectives. For instance, while most robo-advisors do at least make some basic inquiries about an investor’s time horizon for the portfolio, Fein notes that the terms of agreement for at least some robo-advisors explicitly provide that clients will simply be invested according to the robo-advisor’s “plan” or models, and not necessarily in accordance with the investor’s financial situation per se. In fact, Fein’s paper notes that at least one robo-advisor’s disclaimers specifically state that it is the client who is “responsible for determining that investments are in the best interests of Client’s financial needs” and not the robo-“advisor”.

Similarly, it’s not entirely clear whether robo-advisors sufficiently take into account an investor’s overall financial situation in the first place. Fein notes that in the context of the Uniform Prudent Investor Act (UPIA), which describes how fiduciaries should manage investments (primarily in the context of trusts), trustees are expected to evaluate everything from general economic conditions, the possible impact of inflation or deflation, other resources of the trust beneficiaries, needs for liquidity and preservation of capital, and more generally that “investment and management decisions respecting individual assets must be evaluated not in isolation but in the context of the trust portfolio as a whole...” On the other hand, many robo-advisors ask little more than cursory questions about goals and time horizons, and do not necessarily delve into everything from the investor’s cash flow constraints to their tax situation.

Perhaps the most challenging issue for robo-advisors in meeting the Investment Company Act safe harbor is the Rule 3a-4(a)(1)(iv) requirement that “some personnel” of the manager (or investment sponsor) be available to the client, who are knowledgeable about the account and its management. Given robo-advisors have long advertised themselves as being unique precisely because they do not rely on human advisors to interact with clients, it is not entirely clear whether the firms are even sufficiently staffed to meet the requirement. In practice, robo-advisors do still have at least some “customer service representatives”, but in many (or most?) cases they primarily “just” operations staff, and are not legally investment adviser representatives registered to provide advice. In fact, at least one robo-advisor has specifically noted that its “efficiency” by having just 1 client-facing staff member per 10,000 customers, which raises serious questions of whether all clients could possibly have access to the requisite personnel as required by Rule 3a-4.

And notably, the question of whether robo-advisors are sufficiently meeting the requirements to operate as investment advisers is not purely academic. Last year, the SEC and FINRA issued a joint Investor Alert on “Automated Investment Tools”, raising concerns about everything from whether the tools of automated investment services (i.e., “robo-advisors”) are only “programmed to consider limited options”, that the questionnaires used may be “over-generalized, ambiguous, misleading, or designed to fit [the investor] into the tool’s predetermined options”, and that “an automated tool’s output may not be right for [an investor’s] financial needs or goals” (not to mention also raising concerns about whether some robo-advisors may have conflicts of interest due to how they are compensated for certain investments).

Are Some Human RIAs Failing Rule 3a-4 And Operating As An Unregistered Investment Company, Too?

While the dynamics of Rule 3a-4 of the Investment Company Act raise some troubling questions about whether certain robo-advisors are closer to being an investment company than a registered investment adviser providing individualized investment advice, it’s notable that the issue is not unique to robo-advisors.

After all, with the rapid rise of advisors offering an ever-growing array of model portfolios to invest in, either implemented externally through third-party asset managers or internally utilizing one of the leading rebalancing software platforms, arguably many human advisors are offering an investment management service not so dissimilar from robo-advisors! Some commentators – including yours truly – have even advocated for leveraging such technology specifically in order to operate the advisory firm more like a robo-advisor (with similar potential for operational efficiencies).

Yet if robo-advisors are little more than managed accounts implemented with rebalancing software and offered directly to the public, then investment advisers who implement portfolios the same way – and aren’t otherwise mindful of the Rule 3a-4 requirements – may be subject to the same regulatory risk!

In fact, anecdotally I’ve heard from several RIAs recently who offer model portfolios to clients that during recent SEC audits, the examiners have been scrutinizing how customized the client portfolios really are (or not) for each client, and to what extent the firm is at least attempting to have regular annual meeting with clients – ostensibly to meet the Rule 3a-4 requirement that the advisor contacts the client periodically to affirm that the portfolio is still consistent with the investor’s financial situation and investment objectives.

Similarly, the SEC might well scrutinize whether firms that are heavily focused on model portfolios are really capable and prepared to have “exception” clients who do not want to follow the company’s models – as being able to carve out investments that a client doesn’t want is also a specific requirement to meet Rule 3a-4 and avoid having an RIA be treated as an (unregistered) investment company instead. (Notably, firms don’t have to allow clients to modify models by adding securities, but must be prepared to allow clients to modify by excluding certain investments.)

And while many financial advisors have raised the question of whether sending clients quarterly performance statements is “too frequent” and just reminds them of market volatility and makes them anxious, it’s actually a Rule 3a-4 requirement that clients receive detailed statements at least quarterly (though giving clients continuous access to a client portal where they can view investment details at any time would ostensibly be a reasonable alternative). And as noted earlier, periodic quarterly communication to clients is also necessary as a second step to ensure that clients have the opportunity to notify the advisor of a change in financial situation and investment circumstances.

Beyond all of this, there’s still also the fundamental requirement that an investment adviser must fulfill its “know your client” obligations to understand the financial situation and investment objectives in the first place. Of course, as many investment advisory firms are increasingly offer financial planning services and “private wealth management” to differentiate themselves from the competition, there should be little difficulty in meeting the criteria of thoroughly evaluating a client’s financial circumstances, and monitoring it on an ongoing basis (which is part of the financial planning process anyway).

Nonetheless, the point remains that firms focusing solely on investment management, implementing client portfolios using standardized models, and having little advisor interaction with clients (upfront or on an ongoing basis) may actually be operating in a manner so similar to robo-advisors, that the firms could raise similar scrutiny from regulators about whether they are really fulfilling their duties as a registered investment adviser, or are really closer to operating like an unregistered investment company! Similarly – as FINRA recently warned – advisors who are eager to jump onto the “robo-advisor” trend should be cautious that they don’t do so in a manner that causes them to eliminate human interaction and thereby run afoul of the SEC's Rule 3a-4 enforcement!

Is It Better To “Know Your Client” Through Human Advisors Or Technology?

One significant implication of Rule 3a-4 is that human interaction may be a “necessary” factor to evaluate an investor’s upfront and ongoing financial situation and investment objectives. The rule not only expressly stipulates that some “personnel” of the advisory firm (or investment sponsor) should be available to the client for assistance, but the SEC and FINRA joint Investor Alert took pains to articulate the potential flaws and biases of the purely electronic self-directed intake questionnaires of various robo-advisors.

Yet arguably, the reality is that human advisors can certainly be biased in their own process of gathering information about a client, analyzing their situation, and making a recommendation – especially in scenarios where the advisory firm only has one particular type of portfolio models, such that the firm’s advisors can’t get investors unless their clients’ goals are ‘conformed’ to the advisory firm’s standard portfolios.

Certainly, many advisors (hopefully, most!?) will do a thorough job of asking questions and evaluating a client’s financial situation, but there is actually remarkably little regulation clarifying just how deep and thorough an advisor is expected to go in the context of an individual client. (While Fein’s criticism of robo-advisors looks to parallels to the information-gathering expectations in the context of the Uniform Prudent Investor Act, the UPIA is applied primarily in the context of trusts and the fiduciary duty of trustee investment managers, not registered investment advisers working with individual clients.)

In fact, one could make the case that eventually technology may be better suited to the process of consistently information gathering and making consistent recommendations for clients based on their circumstances. After all, humans have well documented biases, that are especially difficult to monitor and manage across an entire firm, and while an algorithm-driven technology solution must be crafted by (biased) humans to begin with, a transparent technology process can be carefully constructed, analyzed, and monitored for appropriate outcomes.

Ironically, then, it’s also possible that robo-advisors facing greater scrutiny of their information-gathering process now precisely because it happens to be consistently applied in a more transparent manner (at least compared to the typical advisor who has a verbal conversation commemorated with a handful of written notes)! Which means if that process really can be continuously refined and improved, perhaps we’ll find in the long run that it’s human advisors who would benefit from a more consistent information-gathering and evaluation process, a la how robo-advisors typically do so!

Ultimately, then, the question of whether robo-advisors are in violation of Rule 3a-4 really highlights a broader question of whether any investment adviser that heavily leverages technology to standardize their investment process is coming too dangerously close to mimicking an investment company. While registered investment advisers working with individuals generally do not manage client accounts on a pooled basis, it may be a distinction without a difference in a world where technology makes it feasible to implement model portfolios that make every client’s account just as identical as it would have been if the investments were in fact pooled. And to the extent that the key differentiator to avoiding being treated as an (unregistered) investment company is the ability to gather (and monitor) an investor’s individual financial situation and investment objectives, in the end is that a task that humans are truly doing better, or is our scrutiny of today’s robo-advisors not because their process is really inferior but simply because they are easier to scrutinize because of the transparency of their process?

So what do you think? Is a robo-advisor more akin to personalized investment advice, or running a disaggregated mutual fund? Are there any human RIAs that might be so "low touch" with technology automation that they may run afoul of the rules, too? Are you thinking about adopting robo tools but concerned about the risks of Rule 3a-4?

Michael, so is the correct step for the robos to also register as investment companies? Therefore they would be on the correct side of both regulations? Shane @ Stockflare

Shane,

Not likely. The scope of this goes far beyond “just” registration. Registered Investment Companies have significant compliance rules and obligations of their own, which are substantively different than RIAs.

This is an either-or scenario, not about dual-registration.

– Michael

If these classifications are mutually exclusive, isn’t there a third possibility? Registering as a broker/dealer. Or does the fact that robos have discretion (albeit circumscribed by a model) preclude that?

As usual, regulation serves to protect old business models… not consumers. Just ask Uber.

Couldn’t have said it better. I’m sure that the SEC / FINRA will regulate on the side that is more profitable for them.

Perhaps the most relevant unresolved question with the emergence of Robos.

SCW

Thanks! Very interesting, and that rundown in the table is helpful.

Some robos are RIAs. For example: “Betterment LLC, an SEC Registered Investment Advisor…. Brokerage services provided to clients of Betterment LLC by Betterment Securities, an SEC registered broker-dealer and member FINRA/SIPC.”

Victor,

Right. The whole legal issue here is whether their decision to register themselves as an investment adviser was improper, because they may not meet the Rule 3a-4 exception to allow it.

– Michael

Lets say robo-advisors were considered an unregistered investment company, could they just register as one and continuing business operations? After briefly looking at one of the robo-adivsor’s website it looks like they provide the financial planning software for do-it-yourselfer’s to address their investment related goals and not other important aspects like debt, insurance, tax and estate. If all the areas of personal finance are not properly addressed your investment portfolio could be negatively impacted and your financial goals derailed. Which leads to a bigger issue, could robo-advior’s be providing a false sense of financial confidence to their clients? In my eyes I believe they are an investment company like a Vanguard, Schwab, Fidelity except they have even less qualified reps to help folks. You get what you pay for and the cost of not speaking to a professional could cost exponentially more the perceive savings.

No, registering the roboadvisor as an investment company wouldn’t work. They are mutually exclusive. An investment co is a separate entity from the sponsor with an independent board who are fiduciaries to the investors. Among other things, the board must ensure every investor is equally treated. Robotically customized portfolios would be impossible.