Executive Summary

One of the fundamental differences between corporations and partnership business entities is that the former faces “two tiers” of taxation – once at the corporation level, and again when profits are distributed as dividends to the shareholder – while the latter are only taxed once to their owners as “pass-through” entities. Of course, the reality is that there are a lot of factors that go into determining the right kind of business entity, beyond just the pass-through taxation treatment or not, though in practice it is often a material factor.

A hybrid mid-point between the two is an S corporation, which is recognized as a corporation for legal purposes – including for liability protection, and transferability of stock shares – but still taxed as a pass-through business, similar to a partnership.

However, in practice the pass-through tax treatment of an S corporation isn’t exactly identical to a partnership, because with a partnership all pass-through income is subject to self-employment FICA taxes (as high as 15.3%), while an S corporation only pays FICA taxes on salary compensation to its owners, and not the remaining profits paid out as nontaxable dividend distributions.

To prevent everyone from just converting partnerships into S corporations that all pay their owners $0 in salary – to completely avoid FICA taxes – the IRS still requires that S corporation owner-employees be paid “reasonable compensation” for the services they render to the business.

Nonetheless, the reality is that for highly profitable businesses, especially with multiple owners and/or multiple employees, there is clearly a portion of profits, over and above just reasonable salary compensation, that can be distributed as a dividend to the S corporation owners, saving FICA self-employment taxes in the process. For profitable businesses, the tax savings can be thousands or even a few tens of thousands of dollars in savings.

Ultimately, not all small businesses can take advantage of these rules. Some don’t meet the ownership requirements of an S corporation, and others are so small and dependent on their owners that realistically, “reasonable” compensation would be 100% of the business profits anyway. Nonetheless, there are many high-income partnerships (or LLCs taxed as such) that might benefit by switching to an S corporation (or making an election for the LLC to be taxed as an S corporation), specifically to split the business profits into FICA-taxable wages and FICA-exempt S corporation dividend distributions. At least, until or unless Congress shuts down this perceived “loophole” and reunifies the taxation of S corporation dividend distributions with the pass-through income of partnerships!

Pass-Through Tax Treatment Of S Corporations

The traditional tax structure of a corporation entails two tiers of taxation. The business itself is a standalone entity that files a tax return and pays taxes on its income. And any of the corporation’s accumulated income that is subsequently distributed as a dividend to shareholders is taxed again (albeit at favorable “qualified dividend” tax rates).

However, the reality is that many small businesses don’t even have a separate entity; instead, they’re simply a sole proprietorship, where the business owner is taxed directly on his/her income. Similarly, many partnerships are really just a combination of individual sole proprietors, and applying this kind of two-tier corporate entity tax structure would be unduly complex, and not representative of the reality (which is simply two individuals coming together in a joint venture).

To accommodate this reality, the tax code recognizes that partnerships can be taxed as a “pass-through entity”, where even though there is legally a separate business entity, the income is not taxed to the partnership entity, and instead is simply passed through in relative shares to partners’ own individual tax returns. In the process, the two-tier double-taxation of corporate income is avoided.

The challenge for some businesses, though, is that they don’t want to structure the business as a partnership (or an LLC taxed as a partnership). In some cases, it’s because of the liability exposure that can still attach to at least the general partners of a partnership. In other cases it’s because there’s a desire to make the business more easily transferrable, especially in small pieces (e.g., for succession planning), and it’s much easier to transfer shares in a corporation than partial interests of a partnership or LLC.

Accordingly, the tax code allows for corporations to make an “S election”. By electing to be treated as an S corporation, the business is nominally a traditional corporation for legal purposes (with all the usual requirements to establish and maintain a corporation), but is taxed as a pass-through entity (similar to a partnership). This allows businesses to enjoy many of the transferability, limited liability, and other benefits of a corporation, but still get the pass-through treatment that avoids two tiers of taxation. (Under the "Check The Box" rules, an LLC can choose to be taxed as a partnership, or taxed as a corporation which subsequently can make an S election.)

However, to prevent potential abuse, the tax code limits the exact kinds of corporations that can make an S election, restricting both the number of shareholders (no more than 100), the types of shareholders (most types of trusts cannot own S corporations), and the classes of stock (S corps can only have one class of stock, albeit with voting and non-voting shares).

Notwithstanding the restrictions, though, for the typical small business owner who wants some of the structural benefits of a corporation, but the pass-through treatment similar to a partnership, the S corporation is an appealing midpoint.

S Corporation Dividends And FICA Self-Employment Taxes

Notably, while S corporations are taxed as a pass-through entity similar to a partnership, the rules are not exactly the same.

When it comes to owners in particular, a key distinction is that with a partnership, any/all income allocable to an active partner in the business is automatically and fully treated as self-employment income, subject to FICA self-employment taxes (Social Security and Medicare employment taxes).

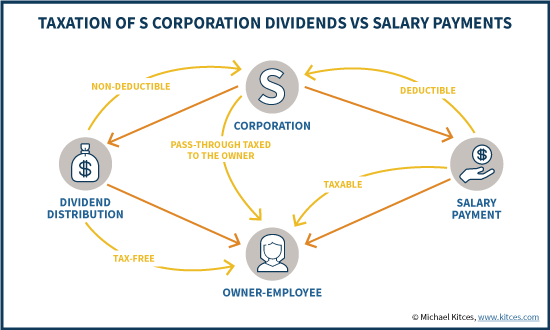

However, with an S corporation, the corporate roots – where payments to owners can occur either as salary compensation for employment, or as a dividend to ownership – is at least partially maintained.

Of course, it doesn’t make sense to pay a traditional “taxable” dividend from an S corporation, because the whole point is that it’s a pass-through entity, where the income of the S corporation is automatically and already taxed to the owners when the business earns it. As a result, taking money out of an S corporation is simply classified as a “distribution” – functionally it’s a dividend, but a nontaxable one because the taxes were already paid when the income was earned by the business to begin with. This ensures that an S corporation is only subject to a single tier of taxation.

Similarly, when an owner-employee of an S corporation receives a salary payment (i.e., for services rendered to the business), the payment is deductible to the business, and taxable to the owner-employee. The net result is substantively the same as an S corporation dividend – the income is only taxed once, to the owner-employee.

An important distinction, however, is that while both the pass-through income of an S corporation, and a salary payment from an S corporation, are ultimately taxable to the owner-employee, at ordinary income rates, their treatment is not identical. Because as “corporate” income, an S corporation’s pass-through income by default is not subject to employment taxes under Revenue Ruling 59-221, since it was not directly earned (even though it’s otherwise treated as ordinary income). By contrast, a salary payment is fully subject to FICA taxes.

In other words, S corporation owners actually have control over whether they will receive their business income as salary, or as a dividend distribution (of previously-taxed pass-through income), where only one is subject to FICA taxes but not the other!

Potential Self-Employment Tax Savings From S Corporations And Reasonable Compensation Requirements

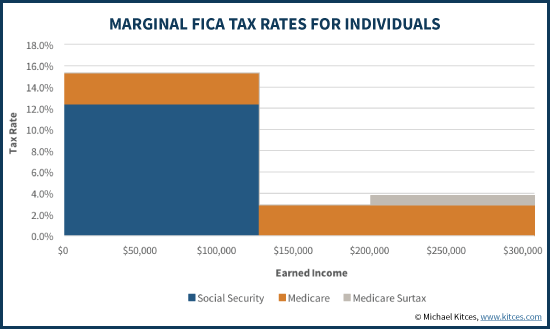

The fact that wages from an S corporation are subject to FICA taxes, but dividend distributions are not, can be a non-trivial impact. FICA taxes include a 12.4% Social Security tax up to the Social Security wage base (which will be $127,200 in 2017), plus another 2.9% of Medicare taxes (for an unlimited amount of income). In addition, there’s another 0.9% Medicare surtax on earned income above $200,000 for individuals (or $250,000 for married couples). In total, this leads to FICA tax rates of 15.3% initially, dropping to 2.9% beyond the Social Security wage base, and rising to 3.8% at higher levels of earned income.

In the logical extreme, then, an S corporation owner should want to pay nothing out as salary, and everything out as a dividend distribution. Since any/every dollar would save a minimum of 2.9%, and as much as 15.3%!

Recognizing this, though, the IRS still prevents a shareholder-employee from completely avoiding employment taxes, by requiring S corporation owners to be paid at least “reasonable compensation” for their actual services rendered to the business. In fact, for more than 40 years now – since Revenue Ruling 74-44 – the IRS has been imputing implied wages to owner-employees who fail to pay themselves reasonable compensation (i.e., recharacterizing their dividend distributions as wages, and applying FICA taxes accordingly).

In other words, if the S corporation earns $400,000 of profits, but the owner-employee did work that would have cost $100,000 for another employee to be hired to do it instead, then the owner-employee must report at least the $100,000 of “reasonable” compensation that would have been paid for that position (and only take the remaining $300,000 as a dividend distribution).

Notably, the exact determination of what constitutes a “reasonable” compensation is ultimately based on the facts and circumstances of the individual owner-employee. IRS Fact Sheet FS-2008-25 notes that relevant factors include the person’s training and experience, duties and responsibilities, time and effort devoted to the business, compensation to other (non-shareholder) employees, what comparable businesses pay for similar services, and more. Or stated more simply, as the name implies, the owner-employee doesn’t have to be paid the ‘maximum’ possible, nor any minimum specified amount; instead, the compensation must simply be “reasonable” for the services rendered. But clearly $0 of salary (and 100% of S corporation dividend distributions) is not reasonable compensation for an active owner-employee involved in the business!

Splitting S Corporation Profits Into Dividend Distributions And “Reasonable Compensation” Wages

Notwithstanding the fact that the tax code requires an S corporation to pay “reasonable compensation” to an owner-employee, in many (or even “most”) cases, an S corporation would still not have to pay all of its profits out as wages subject to employment taxes.

Classifying 100% of S corporation profits as salary might be necessary for a sole owner S corporation with few or no employees, since in that context virtually every dollar of profits really is attributable to the active employment efforts of that owner/employee. But in “larger” businesses with multiple owners and/or employees who all contribute to the value of the business, at some point of the profits of the business are not just a function of the owner/employee, but also of the value of the business itself. That could be value created from the services of non-shareholder employees, or from the capital/equipment of the business – both of which the IRS recognizes as being part of the profits of the business, and separate from reasonable compensation of the owner-employee themselves. Or viewed another way, the whole point of differentiating dividend distributions from salary or other wages is that the latter is a reward for working in the business (and subject to FICA taxes), while the former is the financial reward for creating a profitable business in the first place (and not subject to employment taxes).

In practice, this means that owner/employees will often “split” their total share of the profits between taxable salary wages (subject to FICA taxes), and S corporation dividends that are exempt from FICA taxes.

Ideally, though, the split should not be done based on a percentage of the profits of the business, but instead by starting with what a “reasonable” compensation would be to the owner/employee, with the remaining excess (whatever that is) paid out as profits.

Example 1. Charlie owns a local tutoring business, organizing as an S corporation, that has $700,000 of revenue and 5 employees providing services to customers. In total, his business is on track to generate $200,000 in profits. If Charlie takes all $200,000 as salary, he will pay ordinary income plus FICA taxes on $200,000. If he takes all of the income as an S corporation dividend, he will pay ordinary income on all $200,000, and avoid FICA taxes entirely, but violate reasonable compensation rules in the process. As a compromise, Charlie pays himself a $110,000 salary, commensurate with what it would cost his business to hire another person to manage his 5 employees. The end result is that the last $90,000 of profits avoid FICA taxes, of which $17,200 avoids the 15.3% FICA tax rate, and the last $72,800 avoids the 2.9% Medicare employment tax rate, for a total tax savings of $4,743.

In this example, Charlie cannot eliminate the FICA taxes on all of his income, but he can eliminate a material portion of it, including a slice of income below the Social Security wage base that would have otherwise been subject to a 15.3% FICA tax rate. Of course, this presumes that $110,000 really is a reasonable compensation for the job duties he performs in the business.

For larger businesses, often the reality is that it’s not feasible to push an owner-employee’s salary income below the Social Security wage base, because the business is so large, and the owner’s responsibilities are so substantial, that it wouldn’t be “reasonable” to pay him/her less than a $127,200 compensation package. On the other hand, for very high-income businesses, it can still be appealing to organize as an S corporation, as even “just” the Medicare tax portion of FICA taxes can still produce material tax savings on a large dollar amount.

Example 2. Sheila is the owner of a very successful architectural design firm, organized as an S corporation. Last year, the business generated a total of $2.2M of gross revenue, and produced a net profit of $600,000. If Sheila were to receive all of this income as a salary (or the pass-through from a partnership), it would all be subject to self-employment taxes, with 15.3% on the first $127,200, 2.9% on the next $82,800, and 3.8% on the remaining $400,000, for a total FICA tax liability of $36,773. To reduce her tax exposure, Sheila declares that she will pay herself a salary of $200,000 as the firm’s CEO, a reasonable compensation for the CEO of a service firm in her industry. As a result, she will still pay 15.3% on the first $127,200 of income, and 2.9% on the next $82,800 (up to her $200,000 of wages), but avoids the 3.8% of Medicare taxes on the last $400,000 of income. The net result is a tax savings of 3.8% x $400,000 = $15,200, by splitting her S corporation profits between salary and dividend distributions.

In this example, even though Sheila is unable to avoid the highest FICA tax rates up to the Social Security wage base, her sheer amount of business income still allows for substantial tax savings, by properly classifying a portion of it as a non-FICA-taxable S corporation dividend distribution.

Example 3. Jeremy is a solo financial advisor, organized as an S corporation that is a registered investment adviser. This year, he will gross $350,000 in revenue, and expects to net $250,000 after paying his administrative assistant and his other business expenses. While Jeremy would like to save on FICA taxes, unfortunately the IRS would likely scrutinize taking any of his business income as an S corporation dividend. After all, the reality is that the business revenue is virtually entirely attributable to his services – given that he has no other advisory staff – and there is no capital or equipment producing profits either. As a result, Jeremy will still face FICA taxes on all $250,000 of his S corporation profits, unless he can make a valid case as to why some portion of the revenue and profits really were not attributable to his own work and efforts.

Ultimately, as example 3 illustrates, generating FICA tax savings is still difficult for very small businesses, especially service businesses that rely primarily on the services delivered by a single owner-employee. To substantiate a reasonable compensation that is less than 100% of the profits of the business, the owner-employee must have some way to substantiate that a portion of the profits are not attributable to his/her efforts in the business, such that it really would be a “reasonable compensation” to be paid something less than all the profits of the firm.

Downsides Of Converting To An S Corp (And Paying Yourself Less)

Ultimately, for most small businesses, the potential of converting to an S corporation structure (or adopting one as an LLC), in order to split profits into S corporation dividend distributions and salary compensation, is on the order of thousands (or perhaps a few tens of thousands) of dollars in FICA taxes. The opportunity is especially appealing for high-income partnerships (or LLCs currently taxed as a partnership), that have multiple owners and employees, with substantial profits where there is a reasonably clear delineation between reasonable compensation for the owner/employee jobs, and their profit dividend distributions.

Nonetheless, it’s also worth noting that there are several potential downsides to consider as well.

First and foremost is the cost of making the change itself. There will be filing fees for the new entity itself, but more substantively accounting and legal fees to create the new entity, complete all the requirements to actually form a bona fide corporation (creating and filing Articles of Incorporation, creating a formal leadership team that holds shareholder and director meetings with recorded minutes, etc.), and the time the owners must take to complete the process. Which means it’s probably not a great strategy to engage in for only a single year’s worth of tax savings; at a minimum, the switch should only be done if it’s anticipated to be sustainable and valuable for multiple years, which means the business itself should be longer term and sustainably profitable. In addition, it's worth noting there may be some additional ongoing costs to support the S corporation as well, from a separate business tax return (at least if the business was formerly a sole proprietorship), to setting up or expanding the payroll system and paying unemployment taxes (which may not have already been in place for a solo practitioner style business, or a partnership/LLC where the owners weren't on the payroll system), and some states assess an additional tax on S corporations as well (e.g., California at 1.5%).

The sustainability of the FICA tax savings is also an issue because there’s a non-trivial risk that Congress itself will close this “loophole”. In fact, there have been several proposals in Congress in recent years that would treat S corporation dividends as self-employment income (rendering it fully subject to FICA taxes, such as partnership and LLC pass-through income is). And last year President Obama’s budget proposals included a suggested rule that would subject S corporation dividends to the 3.8% Medicare surtax on net investment income – which means high-income S corporation owners would either find their dividend distributions taxed at 2.9% Medicare plus 0.9% Medicare surtax = 3.8% as earned income, or be subject to the same 3.8% Medicare surtax as unearned investment income, ensuring the government gets its share either way. While the prior legislative proposals have not gained momentum yet, and obviously with a change in President, Obama’s budget proposal will not likely gain traction in its original form, the idea that avoiding self-employment taxes on S corporation dividends is a “loophole” means there’s ongoing risk that the rules could be altered, potentially quite suddenly.

In addition, it’s important to recognize the limitations of the S corporation itself, and affirm they’re not a problem. This includes the limitations on the breadth of owners (no more than 100, though that’s rarely an issue for small businesses), the types of owners (as most types of trusts aren’t allowed as S corporation owners, nor can S corporations be owned by many other entities), etc. For many/most small business partnerships and LLCs, this may not be an issue, because they may have already qualified as such in many small business contexts. But it’s important to be certain that a transition to an S corporation won’t otherwise throw a wrench in the works of future business plans.

It’s also worth noting that paying less in salary to the owner-employee does have at least some potential downside, too. For instance, many/most retirement account contribution limits are based on earned income, so if the owner dials down his/her salary, it dials down the maximum retirement account contribution potential as well (as S corporation dividends aren’t included in determining contribution limits). In addition, workers only get Social Security benefits based on wages subject to Social Security taxes, which means owner-employees who pay themselves less than the Social Security wage base (which produces the biggest 12.4% tax savings) also reduces future benefits. Whether or not that is material to future Social Security benefits depends on the current 35-year average of the owner-employee’s historical wages, and whether/how new years of continuing to work for wages would impact the average wages on which Social Security benefits are based. On the other hand, turning wages into dividends above the Social Security wage base is just pure tax savings with no ‘downside’, beyond the costs and limitations of creating the S corp, and saving at the 2.9% or 3.8% tax rates.

Ultimately, the reality is that converting to an S corporation to minimize self-employment or FICA taxes probably won’t provide breakthrough tax savings for most, especially since the largest portion will come at the 2.9% or 3.8% tax rates. Nonetheless, the tax savings is real… at least, for those who really have profitable businesses – with enough profit to reasonably carve out between dividend distributions and owner-employee salary – and as long as Congress allows business owners to keep making that separation!

So what do you think? How did you decide what tax structure would be best for your own business? Does it make sense to treat S corporation dividends different than salary payments? Will Congress shut down this perceived "loophole"? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!