Executive Summary

The conventional method for evaluating safe withdrawal rates assumes that retirees maintain a stable standard of living through retirement in real (inflation-adjusted) dollars. While there’s nothing unsound about this assumption – at least so long as it reflects a particular retiree’s goals – it is worth considering how accurate this assumption is relative to actually observed retirement spending behavior of the “typical” retiree.

Because, as it turns out from a growing base of research, constant real spending is not particularly realistic for most retirees. Instead, various studies are finding that real spending actually declines throughout retirement, by as much as 1% to 2% per year. And compounded throughout retirement, this discrepancy between standard industry assumptions and actual retiree behavior may be underestimating the safe withdrawal rate.

In this guest post, Derek Tharp – our new Research Associate at Kitces.com, and a Ph.D. candidate in the financial planning program at Kansas State University – analyzes safe withdrawal rates assuming decreasing spending in retirement, finding that the discrepancy between standard industry assumptions and actual retiree behavior may be underestimating the safe withdrawal rate by 0.32% to 0.75% – turning the so-called “4% rule” into something closer to a “4.5% rule” (with subsequently reduced real spending) instead.

While some may argue that “overstating” spending assumptions is good for the sake of being conservative in making retirement projections (certainly it is worse to run out of money that it is to have some extra!), assuming constant real spending is not the only (nor necessarily the best!) way to incorporate a margin of safety. Further, an appropriate safety margin will vary by retiree, depending on their risk tolerance and spending flexibility. If advisors truly wish to give advice that is customized to an individual’s goals and values (as most say they do!), then the safety margins utilized should reflect an individual retiree’s situation, too.

Obviously, the best way to capture an individual’s unique circumstances is simply to create a customized financial plan — which isn’t a radical idea for most advisors — but it is still important to understand what is actually customizable within a plan and what remaining assumptions may be biasing the results. And for advisors who prefer to apply and adapt the safe withdrawal rate to individual retiree circumstances, it’s still crucial to build on the right baseline assumptions – recognizing that the 4% rule may be predicated on retirement spending that simply doesn’t reflect reality!

Assumptions Of Conventional Safe Withdrawal Rate Research

The conventional approach to safe withdrawal rate research, starting all the way back with Bill Bengen’s original 1994 “4% rule” study in the Journal of Financial Planning, assumes that retirees maintain a stable standard of living throughout retirement – which means receiving a consistent stream of cash flow that increases annually with inflation to maintain purchasing power. And the results of that spending pattern are then tested against various historical sequences of returns to determine what initial spending rate is a "safe" starting point.

The logic behind this approach is fairly straightforward. Earlier approaches to securing retirement income tended to focus simply on generating a consistent nominal stream of cash flow throughout retirement, but given the risks of inflation (especially as life expectancies and the retirement time horizon increased), the need for nominally increasing cash flow throughout retirement became more apparent. And exploring both the consequences of inflation and the sequence of inflation (when paired with the sequence of returns), was a key insight of the original Bengen study (along with the impact of sequence of returns).

Of course, retirement researchers need to pick something that can serve as a reasonable baseline for conducting and comparing various withdrawal rate analyses. Assuming constant inflation-adjusted spending (constant real spending) was a logical choice and has continued to function as the baseline retirement spending assumption for nearly every safe withdrawal rate study since.

Observed Spending Behavior Of Retirees

In the decades since Bill Bengen’s original “4% rule” research set a stable-standard-of-living baseline, we’ve gained further insight into the actual spending behavior of individuals in retirement.

And what researchers have found is that both the composition of spending and the level of spending vary throughout retirement – with both tending to change in some predictable ways. As it turns out, on average, most retirees actually experience decreasing rates of real spending throughout retirement.

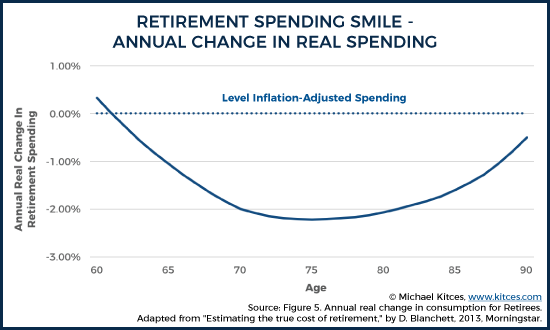

Utilizing consumption data from the Consumer Expenditure Survey, one study from the Center for Retirement Research (CRR) at Boston College found that real retirement spending decreases by about 1% per year throughout retirement. A follow-up study from David Blanchett at Morningstar utilized data from the Rand Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to find that real spending actually increased slightly in the first few years of retirement, but then began decreasing at an increasing rate through the remainder of the first half of retirement (bottoming out at an annual change of about -2.0%), before beginning to decrease at a decreasing rate for the remainder of retirement (ending at an annual change in real spending of roughly -0.5%). This U-shaped real spending pattern found by Blanchett was dubbed the “retirement spending smile”.

Although the CRR and Blanchett studies both found decreases in real (inflation-adjusted) spending, the decreases were small enough that nominal spending would likely at least be stable, or even slightly increasing, throughout the retirement years. In other words, retirees appear to maintain a stable nominal standard of living, or increase it slightly over time… but the increases are small enough that, on average, they don’t even keep pace with inflation, causing a decrease in purchasing power (and thus real-dollar spending) over time.

Nonetheless, the fundamental point is that an assumption of constant real spending – where the retiree increases their spending for the full amount of inflation each year – would project materially higher lifetime spending than what is borne out in the available real-world data.

Safe Withdrawal Rates Under More Realistic Spending Assumptions

So what would safe withdrawal rates look like utilizing more realistic spending assumptions?

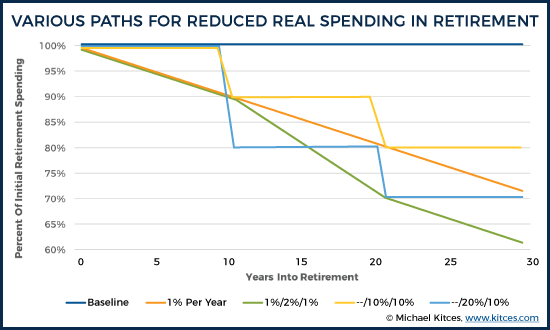

To analyze this question, we can compare a baseline assumption of constant real spending throughout a 30-year retirement time horizon (i.e., the conventional safe withdrawal rate model), to alternative spending patterns in retirement that properly recognize how real spending tends to decrease over time. In this case, we look at four potential decreasing spending patterns: (1) a 1% annual real reduction for 30-years, (2) a 1% annual real reduction for the first and third decades and a 2% annual real reduction for the second, (3) a 10% real reduction after each decade of retirement, and (4) a 20% real reduction in the second decade of retirement and a 10% real reduction in the third.

Notably, these analyses do not delve into how the composition of retirement spending might be changing throughout retirement (e.g., whether discretionary spending might decline at a faster rate, while health care might inflate at a higher rate), and instead, just look at total spending. With these assumptions, scenarios (1) and (3) are consistent with CRR’s findings of straight-line decreases in total retirement spending over time, while (2) and (4) are consistent with Blanchett’s “retirement spending smile”.

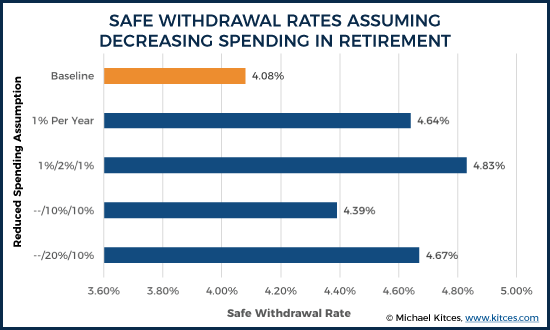

Not surprisingly, lower cumulative spending in retirement results in an increase in the safe withdrawal rate, and the greater the assumed (cumulative) spending cuts, the larger the initial withdrawal rate can be.

(Note: These analyses assume a 60/40 portfolio that is annually rebalanced – where the equities are large-cap U.S. stocks and the fixed-income allocation is Treasury Bills – given the limited benefits of longer-term bonds with interest rate risk from a safe withdrawal rate perspective.)

Overall, the results reveal that reduced spending scenarios result in a safe withdrawal rate increase of at least 0.32%, and as much as 0.75%.

Notably, on a relative basis, this is an initial spending increase of only 8% to 18% (from initial spending of $4,008 per $100,000 of retirement assets up to $4,390-$4,830 per $100,000 of assets) despite the fact that retirement spending is ultimately cut by as much as 30% to 40% in later years. The reason the safe withdrawal rate increase is so modest relative to the total spending decrease over 30 years is in part because spending cuts are assumed to occur gradually over time. And because sequence of return risk is concentrated at the beginning of retirement, it still materially constrains spending. After all, it doesn’t matter if spending is assumed to decrease later in retirement if a combination of bad market returns and high spending in early retirement has already fatally depleted the portfolio by the time the spending slows down.

Nonetheless, in real spending terms, an initial retirement spending increase of 8% to 18% is not trivial, particularly in a world where many retirees have a strong preference for spending more in the “Go-Go” years of early retirement!

Spending Assumptions For Future Safe Withdrawal Rate Research

While the research on safe withdrawal rates to date has certainly provided important insights into retirement planning, it is worth considering what default assumptions are best going forward. The simplicity of the current default assumption certainly has some appeal to it, but in light of growing evidence that it provides an inaccurate depiction of typical retiree consumption behavior, it is worth considering what should be used as the “default” going forward.

Unfortunately, as noted earlier, researchers analyzing retirement spending patterns still aren't in agreement about exactly what the “typical” path of decreasing spending is. Additionally, there’s still debate in the financial planning community about whether or how the spending patterns for the typical mass affluent or high-net-worth retiree might be different than the “average American”.

Nonetheless, it appears likely that at least some kind of reduced-spending-over-time assumption is more accurate than the existing baseline of constant real-dollar spending. Most financial planning software – not to mention more robust Monte Carlo models built by researchers – could easily substitute “inflation-adjusted” spending with “inflation-adjusted minus 1% per year”.

Of course, that’s not to say that research should be confined to the default – if anything, increasing diversity of spending patterns analyzed will help us better understand the varying implications of different withdrawal patterns – but given the non-trivial differences in withdrawal rates under more "typical" retiree spending behavior, some reduced-spending assumption seems prudent as a future baseline for evaluating retirement strategies (e.g., various shapes of equity glidepaths).

More fundamentally, it’s important to recognize that with a baseline assumption of at least some spending reduction over time in retirement, the 4% rule may realistically be closer to a 4.5% rule.

Constant Real Spending As Precautionary Planning?

Some may argue that analyses based on constant real spending are preferable, given that they are inherently more conservative. After all, if retirees actually do decrease their spending throughout retirement, then they will just have an extra cushion with more assets later!

While there may be some comfort in building in a precautionary margin of safety when analyzing a retiree’s situation, similar to utilizing conservative life expectancy assumptions, there is still such thing as being “too” conservative and potentially constraining a retiree’s lifestyle unnecessarily. Further, when utilizing more sophisticated software that can account for various levels of taxation, variable income streams, future inflows and outflows of assets, and other time-based planning considerations, building in a margin of safety by assuming an inaccurate retirement spending "path" could lead to making suboptimal decisions (e.g., an unnecessarily high “path” of retirement spending could unwittingly distort the optimal tax-efficient spend-down strategy across multiple types of retirement accounts).

In addition, it’s important to recognize that there are other ways of handling the uncertainty of retirement projections, short of just making arbitrary (and potentially unrealistically conservative) retirement spending assumptions. For instance, a sensitivity analysis can help to identify which particular risks could be most impactful in order to better monitor them. Additionally, the process of monitoring a financial plan on an ongoing basis provides the opportunity to make mid-course adjustments long before any “severe” adverse scenario occurs. More generally, “safety margins” can be applied with many assumptions beyond just spending, including life expectancy, legacy capital, and return/inflation assumptions.

Furthermore, it’s not necessarily the case that some arbitrary margin of safety is equally appropriate for different retirees. Depending on a retiree’s tolerance or capacity for risk, they may be willing to accept different safety margins for planning purposes. Particularly for retirees who are especially flexible with their retirement spending in the first place, and therefore may be more willing to make mid-course adjustments, if needed.

Ultimately, the best way for any planner to accurately account for a retiree’s unique circumstances and preferences is to simply to create a customized financial plan for that retiree! In fact, even “rule-of-thumb” based approaches like the safe withdrawal rate have significant room to adapt to individual retiree circumstances. Nonetheless, to the extent that the safe withdrawal rate approach will be used, it’s still crucial to consider whether it is appropriate given the baseline assumptions and recognize that given the emerging data on real-world retirement spending, the 4% rule might be better viewed as a 4.5% rule (with declining real spending) instead.

So what do you think? Is it more realistic to assume declining spending throughout retirement? Is it time for a new “default” assumption in SWR research? Should we be concerned about being too conservative in estimating SWRs? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Outstanding analysis! Ultimately this just goes to show that the 4 Percent Rule is still a very creditable tool we can use when it comes to creating a retirement plan that will give us confidence for at least 30 years. I can also identify with your point on being too conservative. Often I think a point of frustration for the average saver is that they are basing their plans on assumptions that are too extreme, and then cutting themselves short trying to reach some nest egg goal that is unrealistic. As you pointed out, there are many other ways we can build more reasonable safety margins into our plans. For those savers who have perhaps gotten a late start or hit a few bumps in the road, evidence to support a SWR in the range of 4.5% is going to seem like a breath of fresh air.

Regarding the fluctuations in retiree spending, I wonder about how much of those changes are driven by the consumer vs. driven by the portfolio. In other words, are the consumers in the survey reducing spending in retirement because they aren’t wanting to spend any more, or are they doing it b/c they don’t have enough money saved to maintain their spending?

For some, it may be a combination of both, but it would be interesting to see a study separate out the spending changes because “I have to” vs. “I want to”. That way we could help clients better target the option to only reduce because they want to.

You bring up a good point. While the studies referenced here look at behavior, understanding the circumstances and motivation behind behavior is important as well. I’m hopeful we’ll continue to gain further insight on these topics with time.

You should consider accounting for discretionary versus mandatory spending. For example does the data show that as the individual ages the discretionary spending decreases and with continued aging the mandatory spending (medical) increases, which might explain the “retirement smile.” Or, is there another explanation? Guidance should take into account these two basic types of spend.

temporary comment: your text and graph don’t match up for the –/20%/10%. You say

“(4) a 20% real reduction in the second decade of retirement and a 10% real reduction in the third” but graph –/10%/20%.

As always, love the article. Thanks!

Hi Jody, Thank you for bringing this to our attention! We are getting the graphic fixed now.

Your analysis uses historical returns. What happens if past performance isn’t indicative of future results, and future rates of return are lower because the starting yields are lower today? Lower returns might more than offset the benefits of declining spending. Of course, only in hindsight will we know what the safe withdrawal rate would have been for any client. Perhaps it’s better to think about a dynamic withdrawal rate that adjusts depending on the sequence of returns?

The analysis is based on the worst historical performance we’ve seen in US history.

Granted, you’re right that it’s not a guarantee the future can’t be worse. But are you really predicting that future returns will be WORSE than the great depression, when the Dow dropped nearly 90% from top to bottom? Because even THAT survived with the withdrawal rates illustrated here (in a diversified 60/40 portfolio).

Not to say that there isn’t a place for dynamic adjustments – we’ve also written about them on this site – but if your baseline recommendation to clients assumes that we’ll have a crash WORSE than the Great Depression, at what point is that so extreme of an assumption that in any “merely bad” market environment retirees still egregiously underspend their wealth?

Remember, the safe withdrawal rate has NO relationship to “average” historical market returns. It ASSUMES bad returns. See https://www.kitces.com/blog/what-returns-are-safe-withdrawal-rates-really-based-upon/ for further detail.

– Michael

Do your safe withdrawal rate calculations take into account investment fees and taxes? If not, then the resulting after-fee, after-tax safe withdrawal rate will be materially lower! In your historical analysis, make sure you use the investment costs at the time of the Great Depression – not today’s lower costs.

Also, the elephant in the room is human behavior, including advisor behavior. How many clients and their advisors have the courage to rebalance their portfolios back to their asset allocation targets during the big drawdown periods? This is a critical element. I’ve been in this industry for 23 years and I’ve seen plenty of clients and advisors fail to do this. It’s always justified at the time, out of an abundance of caution (and fear).

Cern,

You can view a full standalone analysis on the impact of fees and expenses on the safe withdrawal rate at https://www.kitces.com/blog/the-impact-of-investment-costs-on-safe-withdrawal-rates/

– Michael

While Cern’s point seems valid enough, the counter to that is that broader diversification may (perhaps even likely would) prop up the geometric returns (as the prevailing SWR still uses only the two asset classes) enough to effectively counter-balance the fees, thereby allowing us to still use the standard SWR.

Loved this write-up and would greatly appreciate further analysis on this – perhaps even incorporating a more diversified hypothetical portfolio (I’d do it myself but I just quite frankly don’t have the skillset).

” If advisors truly wish to give advice that is customized to an individual’s goals and values (as most say they do!)” – Let’s be honest, most advisors give advice that is minimally (if at all) customized. I am quite sure that many of them just run a robo-advisor (or similar) program and and print out a “customized” plan.

Another way to approach the decreased spending is let it occur “naturally”. People, generally, don’t increase their spending at the rate of inflation. So why not start at a fixed nominal rate, locking in a dollar amount, then come back to review the amount when the NEED arises. This should be years down the road. A review earlier would be needed if a depression type event happens (severe market correction combined with deflation)… This just seems to be a simpler solution.

Excellent blog post, with great links too. As an early retiree, I am curious about spending trends as one ages. We all have ‘life events’ that cause a blip in the spending such as moving to a new home or a medical problem, but the overall trends are important too. Thanks, Derek Tharp, for the insightful post. Hope to read more!

I think I’ll support Wade Pfau and David Blanchet’s (et. al.) point of view that at the 4% of 1994 is now more prudently the 3% Rule of 2015 (or even the 2.4% Rule of 2017!) given today’s market conditions: low 10-year Treasury bond interest rates (2.4%) and high stock PE-10 valuation (29.34) [90% confidence, 20% equities]. Then one can apply the findings of this article If one feels it is reasonable to do so. But a “Safe” withdrawal rate should really be safe, for it is truly better to be safe than sorry w.r.t. this subject matter!

At a 3.5-4.5% distribution rate in a balanced portfolio, you will likely be spending down some portion of capital – more if you factor in fees and inflation. This may be fine if you have sufficient capital and/or have some certainty of expected lifespan, but too many people have insufficient assets saved for retirement and may be forced to spend down assets based on a required dollar amount, rather than a percentage formula. For those fortunate enough to have sufficient assets, the major uncertainties are: how long will I live and what end of life expenses will I need to provide for. Additional uncertainties include: expected long term returns and inflation. I agree that the spending curve in retirement looks like a smile, which suggests to me the wisdom of a much more conservative spending plan in the early years of retirement, say 2.0% or less (not including SS or pension income) in order to better ensure asset sufficiency in the latter stages of life. Most people underestimate how long they will live and have little idea how substantial end of life expenses can be. As a result, the better solution may be to try and match the withdrawal rate to the expected retirement spending curve, rather than adopt a straight line withdrawal approach.

The studies done on actual retirement spending must be studying people who have reached age 80-90+. These people are children of parents who experienced the full force of The Great Depression. They embraced saving and were hard wired to be frugal. New retirees today have different spending habits. They have enjoyed and become accustomed to a higher lifestyle. They are also healthier and are expected not only to live longer but also to be more active longer. We could go back and forth about the pros and cons of increasing your wd rate to optimize your retirement but I subscribe to a more conservative philosophy. I plan for low returns, high inflation and a long life. That way you will either be prepared or over-prepared. If we build up a lead in the early years we can make upward adjustments quite easily but going the other way would be very challenging.