Executive Summary

When an investor is seeking to work with a financial professional, there's a substantial difference in expectations about the nature of the relationship when the professional being consulted is an advisor versus when they're a salesperson. In hiring an advisor, the investor is presumably seeking to put their trust and confidence in someone with their best interests in mind who can advise them on a course of action. Whereas in a sales transaction, the investor is most likely aware that a salesperson's job is simply to sell a product, which puts the onus on the investor (rather than the professional) to evaluate the salesperson's pitch and decide whether or not to act on it.

The difference between an advice and sales relationship isn't necessarily problematic on its own, since some people truly do just want to buy a product from a salesperson, rather than go through the time and cost it takes to be thoroughly advised on the best strategy. However, if an investor is unable to recognize whether they're engaged with an advisor (where they would expect the advice is truly in their best interest) and when they're engaged with a salesperson (specifically intended to sell products), they may be persuaded to take actions that are not truly in their best interests.

As a result of this dynamic, there is a long regulatory history of separating sales and advice, going all the way back to the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, which strictly limited the use of the then-popular "investment counsel" title to be used only by those who were actually in the business of giving investment advice, and forbidding its use by those primarily providing brokerage services. However, by the 1970s, the "investment counsel" term had largely fallen out of use in favor of the more generic (and less regulated) "financial advisor", which grew in popularity as insurance and mutual fund salespeople began to co-opt the title and position themselves as "advisors" while still being both compensated and regulated as salespeople. To this day, slews of professionals from the investment, brokerage, and insurance industries still use the "financial advisor" title without being registered as being in the business of giving investment advice – leaving many investors who hire them confused about how their "advisor" might not actually be an advisor expected to give them advice in their best interests.

Against this backdrop, the U.S. Department of Labor (DoL) has released a new proposed Retirement Security Rule that aims to apply new fiduciary standards to professionals who give investment advice to retirement investors when a relationship of trust and confidence exists between the advisor and the client, which would encompass both registered investment advisers, and insurance agents and brokerage representatives offering advice recommendations as well. But while DoL's proposed rule applies to professionals based on the functions they engage in (e.g., the level of personalization/customization of the advice recommendations), it has also expressed interest (via a Request for Comment on its proposed rule) in how a retirement advice provider's title may or may not create an expectation of trust and confidence. For example, if a professional holds themselves out as a "financial advisor", a prospective retiree who hires them may presume that the professional will provide advice – recommendations that are in their best interest – even if that professional isn't actually obligated to do so.

Arguably, though, the DoL still misses the true significance of the role that advisor titles play. As ultimately, there may be no actual functional difference between the type of questions and the specificity of recommendations made by advisors versus salespeople; instead, the difference between sales and advice is driven by the consumer's expectation of whether they're working with someone in an advice or sales capacity in the first place. Which is first and foremost defined by the way the financial professional titles themselves and markets their services.

As a result, one of the most straightforward ways to re-assert a clearer line for consumers between advice and sales is simply for the DoL to permit insurance agents and brokerage representatives to continue to be salespeople… so long as the professional does not hold themselves out as being a financial advisor or market that they offer financial planning.

Such a "Salesperson's Exemption", which would allow insurance and brokerage salespeople to avoid the DoL's fiduciary obligation in the Retirement Security Rule, would apply to salespersons who (1) avoided holding themselves out as financial advisors or financial planners, (2) avoided marketing that they offer any financial advice or financial planning services, (3) and provided disclosures on all sales presentations or illustrations to the effect that the engagement does not constitute advice and that the consumer should consult an actual financial advisor about the appropriateness of the sales recommendation.

The benefit of such an approach is that it would allow insurance companies and brokerage firms to continue acting in a purely sales function, without meeting the additional regulatory burdens of being a fiduciary advisor. Which would also help the DoL defend against the court challenges it faced with its last fiduciary rule – struck down when the courts agreed that the fiduciary standard should only apply to advisors, and not to salespeople who are not in a "relationship of trust and confidence" with their clients. All of which helps to preserve the regulatory distinction between sales and advice, and also continues to allow retirement investors the opportunity to choose between sales and advice (according to their own needs).

The key point is that even though regulatory bodies have recognized the distinct nature of advice relationships of trust and confidence and applied higher standards of care for such advice relationships in the past, the line between sales and advice has blurred in more recent years. The DoL could help clarify the distinction with a more "truth-in-advertising" approach, by requiring those who market themselves as advisors acting in a position of trust and confidence to retirement investors to be accountable to the fiduciary standards that go along with it, while also providing a path for those who wish to avoid the burdens of fiduciary status to avoid it… by being clear that they really are not advisors, and are simply acting in a sales capacity, so the consumer is clear about the true scope of the relationship.

The Article below is a reproduction of the Public Comment letter submitted by XY Planning Network to the Department of Labor regarding its proposed Retirement Security Rule, and providing a historical understanding of the evolution of regulation and the fiduciary obligations of financial advisors and financial services salespeople.

XY Planning Network ("XYPN") appreciates the opportunity to submit comments to the Department of Labor ("DoL" or the "Department") in connection with the Department's Retirement Security Rule rulemaking process (the "Proposal"). XYPN strongly supports the overall effort of the Department to bring a fiduciary standard of care to all those who provide retirement advice to consumers, and believes this proposal can create long-overdue clarity regarding the role of various market participants as either non-fiduciary sales agents or fiduciary financial advisors providing necessary services to retirement investors.

As part of its role as a support network, XYPN has long advocated for a clear delineation in regulation between professional advisory services and what we also believe is an all-important and necessary complementary role that product vendors play in supporting fiduciary advisory services. And as an organization that requires adherence by its members to an all-encompassing fiduciary standard, we focus our comments on the definition of an Investment Advice Fiduciary (the "Definition") in the Proposal and the Department's invitation to provide comment on the use of advisor-like job titles and marketing practices that result in fiduciary status.

Notably, though, a key tenet of the delineation between sales and advice is that XYPN does not believe that all sales agents who provide recommendations to retirement investors should be subject to a fiduciary standard – only to those actually in the business of advice. Consistent with our view that the role and function of sales agent and fiduciary advisor are separate and distinct, we thus recommend that the Department promulgate a new Prohibited Transaction Exemption ("PTE 2024-01") for sales agents and their affiliated firms selling investment products. This "Salesperson's Exemption" would provide a pathway for sales agents to not be subject to the Department's fiduciary obligations under the Retirement Security Rule, and in exchange would be limited in holding out to the public using certain advisor titles, marketing certain advice services, and would have a proactive disclosure obligation to communicate that they are operating solely in a sales capacity.

We believe this approach and its associated conditions reaffirm the traditional role and limited scope of advice amongst salespeople as purveyors of investment products under securities and insurance laws, while allowing fiduciary advisors to "be able to compete for business on a level playing field", and in a manner consistent with the statutory and common law requirements under ERISA; similar precedents established by the Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC" or "Commission"); Congress; and previous court actions regarding the Department's prior rulemakings.

We begin by offering substantive background on the legislative history of the fiduciary standard for advice-givers in the financial services industry in the wake of the Great Depression, and how regulatory oversight in recent decades has failed to address the use of titles and other marketing practices implying a position of trust and confidence by sales agents, resulting in the widely documented confusion among retirement investors today. We then provide recommendations on how title reform, as part of the DoL's Retirement Security Rule package, can alleviate this problem consistent with the law and court interpretations of ERISA's statutory requirements.

Defining A Fiduciary Relationship Of Trust And Confidence Versus Caveat Emptor

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines advice as a "recommendation regarding a decision or course of action". In other words, advice is about providing direction to someone about what they should do.

By contrast, to "sell" is defined by Merriam-Webster as endeavoring "to deliver or give up in violation of duty, trust, or loyalty and especially for personal gain". As distinct from advice, a sales transaction is about conveying that the seller's offering is a good one worth buying; it's not about whether it's actually right for or in the best interests of the recipient. Instead, it's about the seller's effort to persuade the recipient – for the seller's benefit – and the recipient must then decide whether the seller's case has been persuasively made (or not).

This distinction – between sales and advice – has long been embodied in substantive differences in expectations about how salespeople versus advisors are engaged, the nature of the recommendations that are received, and perhaps most importantly, the standards to which they should be held accountable. As such, sales relationships have long been characterized as caveat emptor – i.e., let the buyer beware, in recognition that salespeople will try their best to sell.

In the context of Federal and state securities laws, sales activities are generally designed to ensure that the sales transaction is suitable, i.e., that salespeople are not trying to sell something that would be wholly inappropriate and unsuitable for the recipient to buy (i.e., a situation where it's not in any retirement investor's interest to be persuaded). In contrast, advice relationships have been recognized for the elevated level of "trust and confidence" that the recipients put into their advice-provider (a condition absent in a sales transaction, literally by dictionary definition)… leaving the customer ill-prepared to assess the advice-provider's recommendation (especially in relationships with asymmetrical levels of information and expertise, where the retirement investor wouldn't naturally be capable of evaluating the accuracy of that advice, thus relegating such advice relationships to a higher fiduciary standard of care).

In other words, both a salesperson and an advisor might make a "recommendation" to a retirement investor, but whether or how much stock the consumer puts into that recommendation is built in no small part on the nature of the relationship between the recipient and whoever is proffering the recommendation in the first place. For instance, a grocery store customer might get a recommendation that "this is a good steak cut to have with dinner", but how that individual interprets the recommendation will be different depending on whether the advice comes from the butcher or their nutritionist, a more easily recognized scenario in which one of the individuals is a salesperson selling meat and the other is an advisor in a relationship of trust and confidence about the consumer's dietary health.

Ultimately, there is a place for both salespeople and advisors – because sometimes the consumer wants to know what to eat to improve their long-term health, and sometimes they're really just trying to buy the right cut of meat for dinner. The fundamental premise here is that a clear distinction between salespeople and advisors is needed no matter the setting – it's crucial to know which type of relationship is in place at the time when the recommendation is made. Otherwise, there's a risk that retirement investors make a presumption they should trust and have confidence in the recommendation as advice, when in reality it's simply a sales pitch that they should have viewed in a different light. Especially since the salesperson has a natural incentive for the recipient to take their sales pitch as advice they would be more likely to act on.

As a result, most recognized professions have taken steps to separate sales from advice, including licensure and registration, standards of conduct, and other regulatory or statutory-defined terms of engagement that help to ensure that consumers only engage with someone who is qualified to be, and held to a standard of conduct appropriate for them to be, an advice-provider in the first place.

Separating Product Sales From (Investment) Advice

When it comes to investment recommendations, policymakers were cognizant of the need to separate sales and advice as evidenced in hearings prior to enactment of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (the "Advisers Act"). At the time, there were both investment counselors who provided counsel (impartial advice) for a fee regarding the investments that their clients should own (or not), and stockbrokers working for broker-dealers who sold stocks and bonds for a commission and whose primary job was to execute those transactions.

During the booming 1920s stock market and the Depression-era that followed, the distinction between sales advice and fiduciary advice had become increasingly muddled. The trouble was that when customers received a recommendation that "this stock can bring you financial success", it wasn't necessarily clear whether the individual was an investment counsel who the investor could place their trust and confidence in for impartial advice, or simply a broker touting their firm's inventory of stock holdings that needed to be sold that day. Consumers had become overly reliant upon salespeople for advice (and by misunderstanding the broker's sales tactics, failed to discern the advice as a broker's sales recommendation), leaving advice-givers to struggle in distinguishing their objective advisory services from the sea of salespeople.

The end result was that, during congressional hearings in 1940, it was the advice-providers themselves – led by the Investment Counsel Association of America (ICAA, renamed the Investment Advisers Association in 2005) – who welcomed higher standards for themselves and their advice-giving peers, in the form of title protection for the term "investment counsel" and regulation regarding the registration and standard-of-care requirements that would apply if one represented that they provided investment counsel services. As made clear, an SEC study in 1939 found that the brokerage industry had intertwined its product-sales business with investment advice, such that "the availability of such [an advice] service to investors created an additional incentive to a purchaser… to patronize particular brokers or investment bankers with the resultant increase in their brokerage or securities business", and acknowledging "the problem [for consumers] of distinguishing between bona fide investment counselors and the 'tipster' organizations [selling investment products]". An ICAA witness testified in a hearing on the Advisers Act that "some of these organizations using the descriptive title of investment counsel were in reality dealers or brokers offering to give advice free in anticipation of sales and brokerage commission on transactions executed upon such free advice…"

Consequently, when the Advisers Act was enacted into law, the House Committee report declared that the Act was established to:

…protect the public from the frauds and misrepresentations of unscrupulous tipsters and touts and to safeguard the honest investment advisers against the stigma of the activities of these individuals… [and took] especial care… in the drafting of the bill to respect this relationship between investment advisers and their clients.

The Supreme Court reaffirmed the fiduciary duty of investment advisers to clients in SEC v. Capital Gains Research Bureau, stating that "The Investment Advisers Act of 1940 thus reflects a congressional recognition 'of the delicate fiduciary nature of an investment advisory relationship,' as well as a congressional intent to eliminate, or at least to expose, all conflicts of interest which might incline an investment adviser – consciously or unconsciously – to render advice which was not disinterested."

The distinction between – and separation of – sales from advice was so foundational to the emergence of investment counsel providing advice in a relationship of trust and confidence, as a distinct profession from brokerage sales, that when the Advisers Act was under review in the House and Senate, Congress took several steps to ensure that while brokerage firms would be allowed to continue to render their important functions in the economy as sales-based organizations, sales and advisory activities were separated.

The first step was a mandate under Section 202(a)(11) of the Advisers Act that investment adviser registration (and the attendant standard of conduct for investment advisers) will be required for "Any person who, for compensation, engages in the business of advising others… as to the advisability of investing in, purchasing, or selling securities", unless a specific exemption applied.

In turn, to acknowledge that there were other industry participants who may still be involved in aspects of a client's financial matters, Section 202(a)(11)(B) created an exemption that "any lawyer, accountant, engineer, or teacher whose performance of such [advice] services is solely incidental to the practice of his profession" will not need to register as an investment adviser. Similarly, Section 202(a)(11)(C) of the Advisers Act declared that "any broker or dealer whose performance of such services is solely incidental to the conduct of his business as a broker or dealer and who receives no special compensation therefor" would also be exempted from investment adviser registration.

On the other hand, to prevent brokerage firms from marketing themselves as offering advice services as investment counsel when their recommendations were, at most, "solely incidental" to their sales activities (and to prevent them from nominally giving advice only to later claim that they weren't acting as such, in order to avoid the fiduciary accountability that would otherwise apply), Congress included Section 208 in the Advisers Act. Section 208 explicitly states that:

It shall be unlawful for any person registered [as an investment adviser] to represent that he is an investment counsel or to use the name 'investment counsel' as descriptive of his business unless: 1) his or its principal business consists of acting as investment advisers; and 2) a substantial part of his or its business consists of rendering investment supervisory services.

[Where "investment supervisory services" is subsequently defined as "the giving of continuous advice as to the investment of funds on the basis of the individual needs of each client"].

Moreover, Congress also stated in Section 208(d) that it was not permissible to try to indirectly work around such limitations on how investment counsel services are represented to the public if they would not be permitted directly in the first place.

The end result of the congressional framework in the Advisers Act was that:

- If someone held out as being in the business of financial advice for compensation, they had to register as an investment adviser and be subject to its associated (fiduciary) standard of care;

- A brokerage firm could only avoid investment adviser registration if its advice were "solely incidental", and it did not receive special compensation for any advice it did provide;

- If a firm engaged in both brokerage sales and investment advice, it still couldn't market that it provided "investment counsel" advice services unless its principal business was acting as an investment adviser (which is important because if advice was its principal business, it would be impossible for such firms to later claim that their advice was "solely incidental" at the time of implementation).

In summary, a key purpose of the Advisers Act was to create a clear separation between the "tipsters and touts" operating unregistered or as stockbrokers, and "bona fide investment counsel" of the investment adviser. And in order to do so, at its core, the Advisers Act was centered on how firms marketed and held their services out to the public in the first place, with a regulatory framework that forced securities firms to declare whether their primary or principal business was providing brokerage services where their agents would operate as salespeople, or providing investment counsel (as fiduciary advisors with no conflicted brokerage services because of the fiduciary obligation that applies to relationships of trust and confidence).

Evolution Of The Market(ing) For Financial Advice

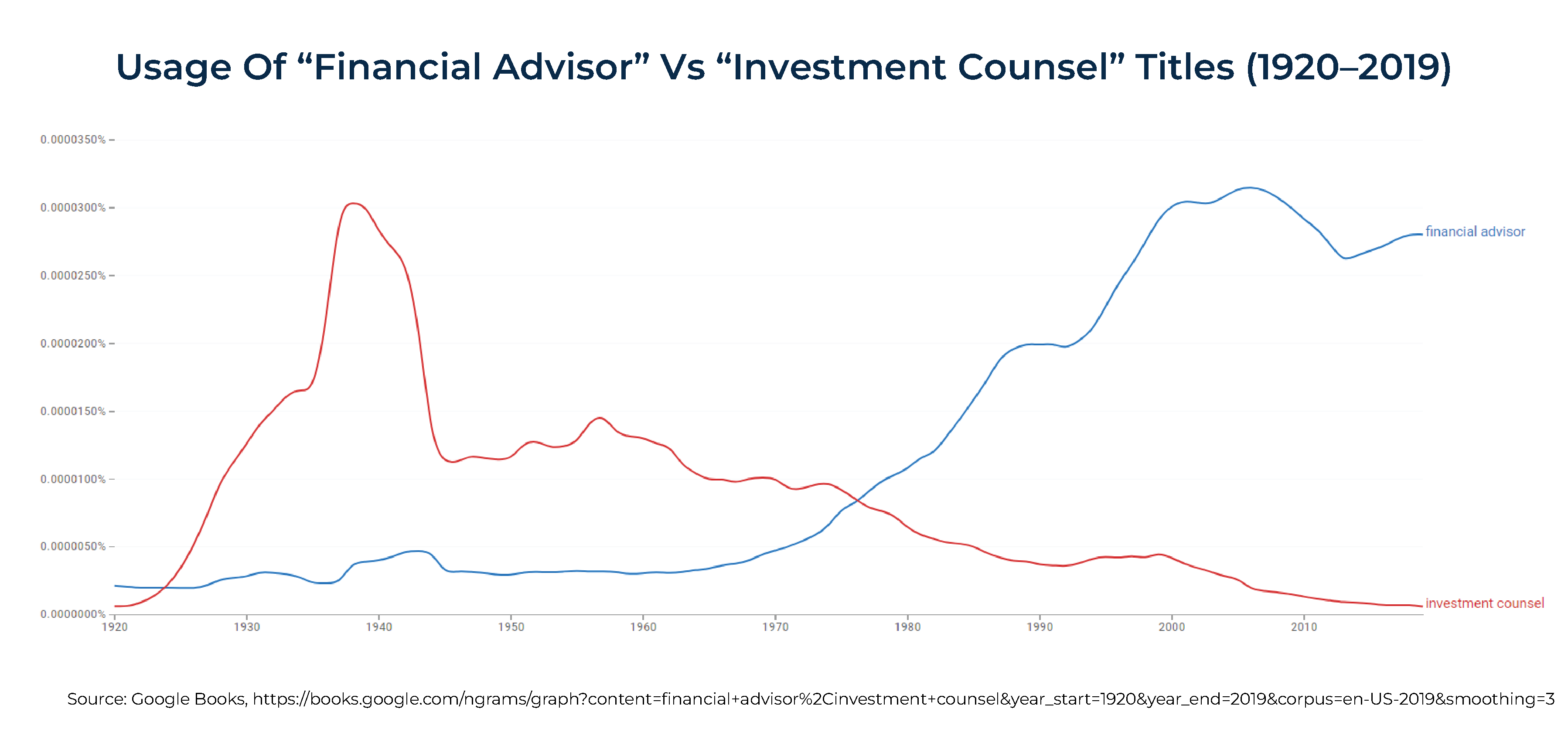

The Advisers Act was successful at reining in then-problematic and blurred lines between broker-dealers and investment counsel firms, and in particular, by prohibiting the use of what had rapidly become a popular title of "investment counsel" in the preceding 20 years to only those who were bona fide fiduciary advisors, resulting in a decline in the general use of the term.

However, after several decades of stability and clearer delineation between brokerage and investment counsel services, industry nomenclature began to shift to other advisor-like titles used by securities brokers. In 1975, the SEC deregulated fixed trading commissions in what was known as "May Day". The result in the marketplace was to allow brokerage firms to set their own rates on trades and compete with each other on price, leading to a rise of "discount" brokerage firms that aimed to use emerging new technologies (in the form of personal and mainframe computers) to disintermediate human stockbrokers and force them to reinvent themselves above and beyond 'just' selling a stock or a bond or mutual fund).

Another consequence was a dramatic increase in use of the term "financial advisor" by the securities industry as it sought to expand its value proposition beyond sales transactions alone. At the same time, use of the word "counsel" itself became less popular within the English language, co-opted by words like "advice". Such that even the organization that championed the original Advisers Act legislation to protect the business of "investment counsel" – the Investment Counsel Association of America (ICAA) – in 2005 changed the organization's name to the Investment Adviser Association (IAA), in recognition of the shift in industry language and terms away from Investment Counsel.

At the same time, a corresponding shift in the insurance industry was also underway. In the post-World-War-II era, the term "investment counselors" was still predominant in the advisory industry, catering largely to affluent, high-net-worth investors who could afford to hire a personal investment manager. For the average American, an "investment" was more commonly a whole life insurance policy with a guaranteed cash value, and notably the founding organizers of what became the financial planning movement, and the Certified Financial Planner marks were, in 1969, a mutual fund salesman named Loren Dunton, and a life insurance salesman named James Johnston, who came together to expand their sales roots into a more holistic advice proposition.

In fact, as noted in "The History of Financial Planning", as late as 1960, life insurance was the substance of financial planning… "By definition, a financial planner was an insurance man who offered the public more than money-if-you-die" with an increasing volume of add-on financial planning advice regarding the household's spending and cash flow, taxes, estate bequests, and similar domains that remain the staple of the financial planning curriculum today.

In fact, as noted in "The History of Financial Planning", as late as 1960, life insurance was the substance of financial planning… "By definition, a financial planner was an insurance man who offered the public more than money-if-you-die" with an increasing volume of add-on financial planning advice regarding the household's spending and cash flow, taxes, estate bequests, and similar domains that remain the staple of the financial planning curriculum today.

However, the rise of media publications dedicated to personal finance, amplified by the growing accessibility of the internet in the 1990s and especially the 2000s, led consumers to decrease their use of permanent insurance as an investment solution (albeit with a relative shift to the adoption of annuities as an investment vehicle), and a similar pressure to shift from a pure sales function into an ever-more "consultative selling" approach built around providing more comprehensive financial advice before implementing (i.e., selling) whatever products came out of the consultation. Such that, like the IAA, in 1999, one of the original insurance agent trade groups, the National Association of Life Underwriters, also changed its name to reflect the new titles used by its members – the National Association of Insurance and Financial Advisors ("NAIFA").

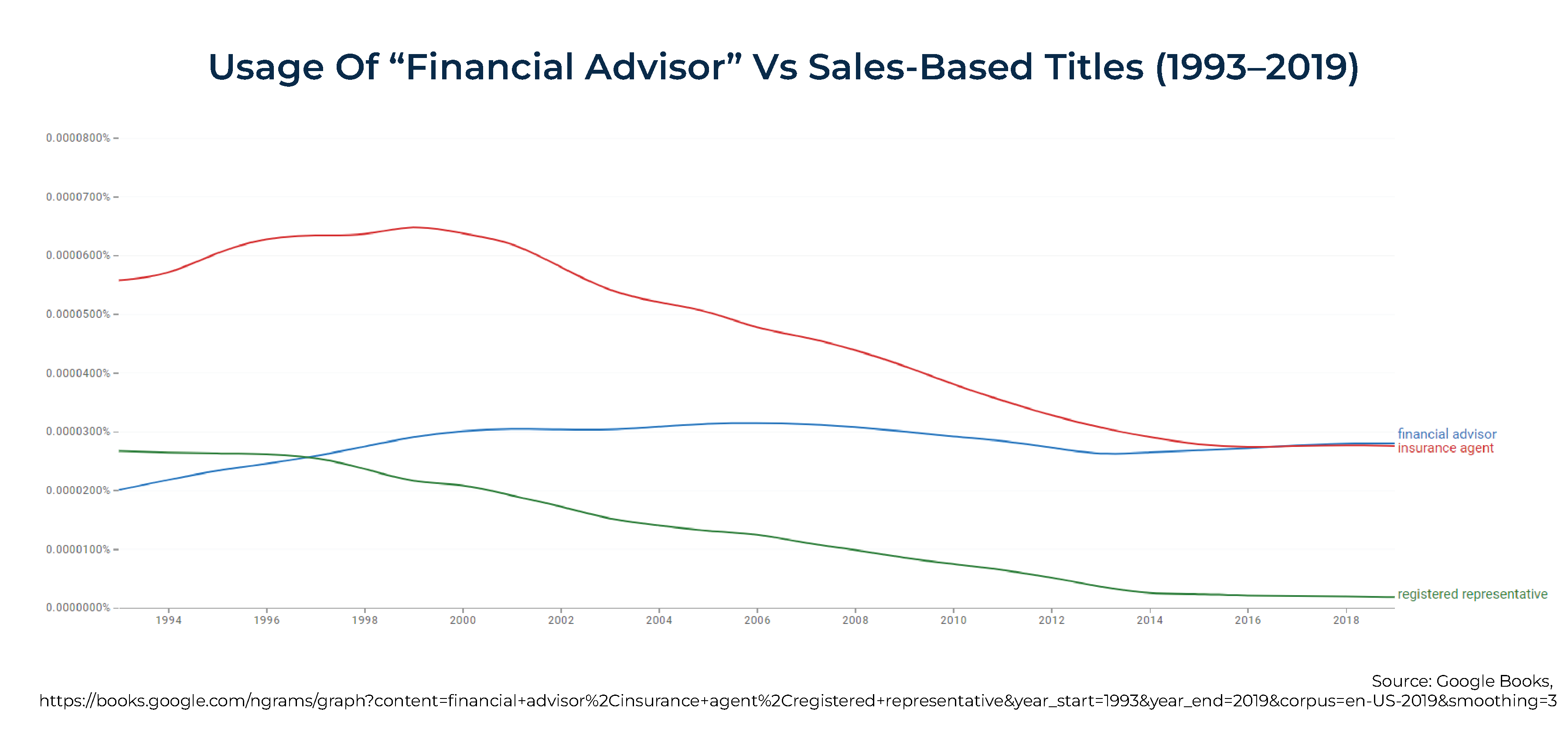

The end result is that, over the past 30 years in particular, there has been a relative collapse in the use of traditionally descriptive sales-based titles like insurance agent of an insurance company (down more than 50%) and registered representative of a broker-dealer (down more than 93%), into the more ubiquitous and advice-oriented title of "financial advisor" (up nearly 40%).

In other words, the past 30 years have seen a massive shift in how traditional sales roles like agents of insurance companies and registered representatives of broker-dealers hold themselves out to the public, by adopting advisor-like titles and marketing advisory services. Confirming this trend, in 2017, the Consumer Federation of America conducted a study and found that 25 of the largest insurance companies and broker-dealers substantively market themselves as offering advice services and using advice titles, even as they continued to rely on the regulatory standards that apply to salespersons.

How Misleading Marketing Creates Expectations Of Trust-And-Confidence Advice Relationships

With the relative decline of sales-based titles and the rise of more ubiquitous "financial advisor"-type titles by those sales organizations, regulators aptly responded by saying, "If everyone's going to call themselves a financial advisor, then we'll regulate them all as financial advisors", leading to the rise of various "uniform fiduciary standards" by the SEC and FINRA (Regulation Best Interest) and the NAIC (Annuity Suitability & Best Interest Standard), to apply what was historically the advisor's best-interests standard to commissioned salespeople when they give product recommendations.

The caveat, though, is that many of the sales agents who use the title "financial advisor" still are not legally in the business of dispensing investment advice – they are licensed as insurance agents or as registered representatives of brokerage firms, and not as investment adviser representatives of registered investment advisers. As the Department knows from experience in approving the 2016 fiduciary rule, trade groups for industry product manufacturers and distributors, who employ financial salespeople, have vigorously opposed expanding fiduciary status to sales-oriented firms in the insurance and securities industries. In comment letters and in administrative law briefs challenging the 2016 rule, those product manufacturers and distributors maintained that sales are and should be separate from advice, and that applying a fiduciary duty to sales activities would quash out an important sales function for consumers looking to access a salesperson to purchase a product.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit agreed when it vacated the Department's prior fiduciary rule. In Chamber of Commerce v. DoL, the Court reasoned that "[s]tockbrokers and insurance agents are compensated only for completed sales, not on the basis of their pitch to the client. Investment advisers, on the other hand, are paid fees because they 'render advice'." The Court also noted that the Department's 2016 rule "expressly includes one-time IRA rollover or annuity transactions where it is ordinarily inconceivable that financial salespeople or insurance agents will have an intimate relationship of trust and confidence with prospective purchasers". Which is not a statement about the nature of advice in one-time transactions as much as it was a tacit acknowledgment by the Court that financial salespeople and insurance agents are not in advice relationships of trust and confidence with retirement investors.

Except, as it turns out, while the Fifth Circuit held "financial salespeople are not fiduciaries absent [a] special relationship", consumer research suggests that when salespeople use advisor-like titles, they actually do create that very expectation.

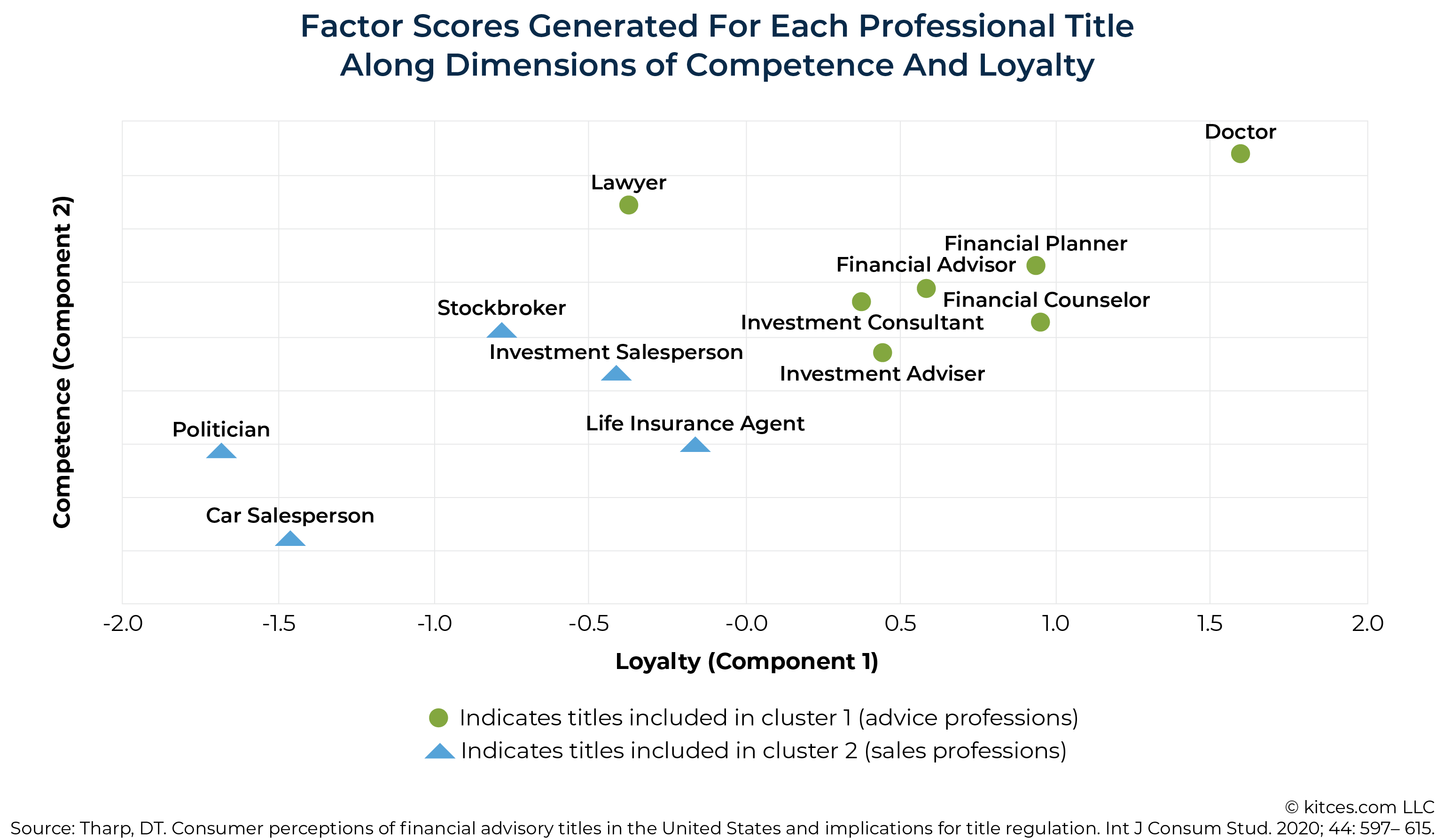

For instance, research by Dr. Derek Tharp, entitled "Consumer perceptions of financial advisory titles in the United States and implications for title regulation" in the International Journal of Consumer Studies, finds that when consumers are asked about their expectations on various dimensions of Loyalty (a measurement of their trust in the advice relationship) and Competence (a measurement of how much confidence they believe they can have in the advice relationship), there is a material difference between advice-like titles and sales-like titles.

The results showed that consumers place greater Competency confidence in titles like Financial Advisor, Financial Planner, and Investment Adviser, than they do in titles like Stockbroker, Investment Salesperson, and Life Insurance Agent. Similarly, on the basis of titles alone, consumers accurately predicted who to trust, whether the professional's loyalty rested primarily with themselves and their company (a negative score on the Loyalty scale below), or whether the professional's loyalty was tilted in the consumer's best interests (a positive score on the Loyalty scale below).

In other words, the fundamental disconnect is that when salespeople are permitted to use advice titles and represent that they're in the advice business, they create an expectation of an advice relationship of trust and confidence. Such that consumers literally don't understand subsequent industry disclosures about how some "financial advisors" may not be obligated to act in the consumer's best interest (leading to a wide range of studies showing ongoing consumer confusion between brokers and investment advisors). Because at the point that the person markets themselves as being a "financial advisor" offering advice… the advice (not sales) relationship is already established.

Separating Sales From Advice To Preserve Consumer (And Industry) Choice

The fact that aggressive marketing practices can be misleading to retirement investors is not a new development. Over the years, regulators have responded with various forms of "truth in advertising" requirements across a wide range of industries, all predicated around the idea that regulators don't necessarily need to specify what the private market does and does not sell; instead, oversight and ultimately enforcement can be applied to ensure that firms actually deliver on what they promise. And if they can't deliver it, then they aren't permitted to market that they do.

In this context, the Advisers Act was itself largely a "truth-in-advertising" approach to the regulation of investment advice, with the outright requirement under Section 208(c) that firms could not hold out as investment counselors or offering investment counsel services unless they were principally in the business of providing such services. This requirement, in turn, necessitated registration as investment advisers and subject to a fiduciary standard of care. And in the absence of a full exemption from registration, such as was (and remains) available for banks, the brokerage firm or agent could not use the term "investment counsel" as their "principal business" was executing securities transactions, not providing investment advice (unless it was 'solely incidental' to their brokerage services). Advisors and salespeople had to be clear regarding the standard of care that applied to the capacity in which the agent and firm were operating.

In 2019, the SEC addressed the issue of titles used by non-fiduciary advisors. In adopting Regulation Best Interest as an upgraded market conduct standard for securities brokers, the Commission stated that:

We believe that in most cases broker-dealers and their financial professionals cannot comply with the capacity disclosure requirement by disclosing that they are a broker-dealer while calling themselves an "adviser" or "advisor".

Accordingly, the SEC's solution limited the use of the 2 related terms:

As a result, we presume that the use of the terms "adviser" and "advisor" in a name or title by (i) a broker-dealer that is not also registered as an investment adviser or (ii) an associated person that is not also a supervised person of an investment adviser to be a violation of the capacity disclosure requirement under Regulation Best Interest.

Notably, this framework is substantively similar to the Department's approach, which deems that a person is an investment advice fiduciary if they provide investment advice or make an investment recommendation to a retirement investor, the advice or recommendation is provided "for a fee or other compensation, direct or indirect", and the person makes the recommendation in one of the following contexts under paragraph (c)(1) of the Department's "Retirement Security Rule" Proposal:

- The person either directly or indirectly (e.g., through or together with any affiliate) has discretionary authority or control, whether or not pursuant to an agreement, arrangement, or understanding, with respect to purchasing or selling securities or other investment property for the retirement investor;

- The person either directly or indirectly (e.g., through or together with any affiliate) makes investment recommendations to investors on a regular basis as part of their business and the recommendation is provided under circumstances indicating that the recommendation is based on the particular needs or individual circumstances of the retirement investor and may be relied upon by the retirement investor as a basis for investment decisions that are in the retirement investor's best interest; or

- The person making the recommendation represents or acknowledges that they are acting as a fiduciary when making investment recommendations.

However, the Department's mostly functional approach to fiduciary status differs from the combination title/functional approach adopted by Congress when the Advisers Act was signed into law, and the SEC's title restrictions in Regulation Best Interest, by not taking a more proactive stance with respect to the use of titles and how financial professionals hold themselves out to the public.

That said, the DoL has acknowledged in its Request for Comments that "an investment advice provider's use of such titles routinely involves holding themselves out as making investment recommendations that will be based on the particular needs or individual circumstances of the retirement investor and may be relied upon as a basis for investment decisions that are in the retirement investor's best interest". As such, the Department should be commended for inviting comments "on the extent to which particular titles are commonly perceived to convey that the investment professional is providing individualized recommendations… [and] whether other types of conduct, communication, representation, and terms of engagement… should merit similar treatment."

While we believe that the Department is right to be concerned with the impact of advisor titles and the impression conveyed to retirement investors, we believe that an alternative approach to regulating this reality may further enhance protection for retirement investors, as well as "level the playing field" for fiduciary advisors, as referenced in the Department's Fact Sheet.

The Salesperson's Exemption From The Retirement Security Advice Rule

When it comes to "truth-in-advertising" approaches to regulation (i.e., the use of misleading titles and marketing practices), there are 2 ways to accomplish the goal.

The first, as embodied in the approach taken by the Advisers Act and subsequent SEC guidance, is to apply consequences to brokers and others who use prohibited advisor-like terms such as "investment counsel", "financial planner", and "adviser" unless dually registered under the Advisers Act. The original Sec. 208(c) restriction on the use of " investment counsel", which remains unchanged, prohibits a person from either "represent[ing] that he is an investment counsel or to use the name 'investment counsel' as descriptive of his business", effectively restricting the use of the title of investment counsel (the common label of the era) or, alternatively, regulating the function of acting as "an investment counsel" (i.e., to provide fiduciary advice).

In other words, to the extent that a firm or its agents market that they provide such financial-advisor services to retail investors (by functional service or title), they are required to actually be in the business of providing those services, and subject to the regulatory consequences (from registration to standards of care) that apply. For which regulators can then periodically modernize those definitional triggers as needed. (For additional background on title restrictions, please see XYPN's petition for a rulemaking filed with the SEC.)

The alternative approach is to provide a prohibited transaction exemption for those who do not have to meet the additional regulatory fiduciary burdens attendant to being a financial advisor, as long as they do not use such titles or market such services. We believe this is more consistent with the Department's statutory authority (and under the common law of trusts) to both regulate advice to retirement plans, and to grant administrative exemptions under §1108 that provides the Department with the authority to grant such exemptions (as long as the exemption is administratively feasible, in the interests of the retirement investors, and protective of their rights).

In this context, XYPN proposes an exemption (either as PTE 2024-01, or modifying one or more of the existing PTEs cited in the rule package, as appropriate) for salespersons, who would not need to comply with the Department's Retirement Security Rule and its fiduciary obligations… as long as they are clear and explicit that they are operating in a sales capacity to retirement investors.

At its core, we envision that the Salesperson's PTE would have 3 core prongs:

- Proscribed Titles. Certain titles, that clearly and unequivocally convey the expectation of an advice relationship, would be proscribed from use for those who wish to avoid the scope of the Retirement Security Rule; such titles would certainly include "financial advisor" itself (conforming to the SEC's similar application in Regulation Best Interest), and could also include "financial planner" (which triggers registration with Federal or state securities regulators and is also prohibited for use by the NAIC model Unfair Trade Practices Act when only engaged in sales practices) and "wealth manager" (which similarly is commonly used by the industry to connote a more comprehensive advice offering, and implies ongoing "management" of client assets).

- Proscribed Services. The service of "advice" itself would not be permitted in the marketing and advertising materials of firms relying on the new or updated PTE to avoid the Retirement Security Rule (such that even if a salesperson sought to use an alternative title to imply that they offer advice services, they could not describe themselves as offering advice services and operating in an advice capacity while relying on the exemption). Services could not be offered directly, or indirectly through or together with any affiliate. Additionally, the PTE could cite the aforementioned NAIC's model Unfair Trade Practices Act that prohibits certain advisory activities, such as financial planning, when the insurance producer is engaged only in the sale of insurance or annuity policies.

- Capacity Disclosure. In the firm's marketing and advertising materials, and in its subsequent sales presentations or product illustrations, the firm would be required to display a prominent disclosure that states to the effect that, "This is not an advice engagement. Consumers may wish to consult a financial advisor regarding the advisability of engaging in any recommended transactions".

Relative to the Proposal, the PTE would be applied as a prospective exemption from one of the "contexts" in paragraph (c)(ii) – specifically, that the person would be deemed to not be in the business of making investment recommendations upon which the retirement investor relies upon… because investors rely upon (and place trust and confidence in) advisors who provide such recommendations, and not salespeople. The new or revised Salesperson Exemption PTEs, and their associated Capacity disclosure in particular, would also further substantiate paragraph (c)(iii), that the person is not acting as a fiduciary when making investment recommendations, because they have clearly described their capacity as a non-fiduciary salesperson.

Implications And Considerations Of A Salesperson's Exemption

As more than a decade of effort by the Department to update the ERISA definition of fiduciary helps illustrate, it's difficult to determine when, exactly, a sales relationship ends and an advice relationship begins. It's an issue further complicated by a diverse industry with multiple channels and business models, a wide range of retirement investors that are served, made even more challenging by the self-interest of product manufacturers and distributors defending a regulatory environment for arms-length transactions in which they can sell products under the guise of advice that consumers can trust and be confident in.

The benefit of a Salesperson's Exemption framework is that it's a PTE that clearly permits sales organizations to continue to operate as sales organizations, in accordance with the Fifth Circuit's views that the Department exceeds its jurisdiction when it tries to apply a fiduciary advice framework to those who are not actually in the business of advice. Such an Exemption does not curtail or limit the manufacturing and distribution business models of the firms involved; it merely requires them to be as clear with their customers in their own sales and marketing materials as their trade groups were in asserting in legal briefs that they are in fact operating in a sales capacity and not an advice relationship of trust and confidence, with a clear Capacity Disclosure, and the proscription of certain advisor titles and advisory services.

Notably, though, such titles and services are not actually limited from a First Amendment perspective. Instead, as the Supreme Court decision in Central Hudson Gas and Electric Corp v. Public Service Commission long ago determined, false or inherently misleading commercial speech is not constitutionally protected. Or stated simply, akin to yelling "fire" in a crowded theater and, based on a wide range of truth-in-advertising laws, the point is simply that if industry participants choose to use certain words, they are subject to the Department's Retirement Security Rule and must accept the (fiduciary) consequences that follow from being legally required to actually provide the services they're marketing. It's up to the firms to decide whether to commercially market themselves in a manner that necessitates a fiduciary standard… or not.

In turn, because the Salesperson's Exemption is a PTE that preserves current sales-based business models and practices, it also preserves consumer choice and access to those services, and instead of curtailing them simply reframes them more effectively as a choice between sales or advice – recognizing that there is a time and place for each, just as in some instances the shopper might want advice from her nutritionist on how to eat healthier, and at other times rely on the butcher for a recommendation on the best cut of meat to buy for dinner. And as the aforementioned Tharp research has shown, consumers actually do understand the difference in a professional relationship (and the associated difference in trust and confidence) between sales and advice.

A Salesperson's Exemption also reduces the risk of problematic "regulation by enforcement" challenges in the future, where the Department may have to determine in real time, as the Retirement Security Rule is enforced, how to parse the dividing lines between when a sales relationship ends and an advice relationship of trust and confidence begins.

Ultimately, it is clear that such a separation must exist – relative to the demands of both the marketplace and the Fifth Circuit – and so the Department will inevitably be forced to make such a delineation anyway in the end. A Salesperson's Exemption provides a clearer basis for all industry participants to understand in advance how to navigate the environment, while also arguably providing the Department more latitude to enforce the Retirement Security Rule itself more stringently in situations where firms proactively choose not to utilize the safe harbor of the Salesperson's Exemption (and ostensibly would now bear the burden of proof to show why they are still not in the business of advice and are only operating as salespeople if they're also choosing not to utilize the Salesperson's Exemption).

At the same time, the Salesperson's Exemption is also consistent with the transaction-by-transaction basis for functional regulation under ERISA. Unlike regulation of investment advisers under securities laws, ERISA service providers are not "24/7" fiduciaries but rather fiduciary status is dependent upon the facts and circumstances. The PTE framework proposed by XYPN would not automatically attach a fiduciary advice obligation to the entire relationship. Instead, each discrete transaction would be assessed by the (advisor-or-not) titles that were used leading up to that particular transaction (or the original relationship that subsequently led to that transaction), the (advice-or-not) services that were promised leading up to that particular transaction, and whether the Capacity Disclosure was provided anew for each particular transaction.

Though notably, it does also mean that if a consumer first engages a brokerage firm as a client for their advice services, that would remain the nexus point by which the consumer engaged the service-provider, effectively making it impossible for them to subsequently convert to the Salesperson's Exemption later with the same consumer. As again, the whole point is that a relationship first founded on the premise of advisor-based marketing of a relationship of trust and confidence makes subsequent transactions in that relationship founded on the same relationship of trust and confidence.

The Salesperson's Exemption also maintains regulatory consistency with the SEC, which similarly has proscribed the use of "financial advisor" for pure sales roles at broker-dealers under Regulation Best Interest, and the Investment Advisers Act that proscribes the use of "investment counselor" titles or marketing "investment counsel" services unless principally in the business of advice (with the attendant registration and fiduciary obligations). Albeit repackaged in the form of an administrative exemption that is more consistent with the Department of Labor's ERISA rulemaking framework.

It's also notable that while industry product manufacturers and distributors will likely object to being required to make such disclosures and oversee the use of such terms, it is already common practice for them to provide nearly identical disclosures and proscribe titles for their own agents and representatives as it pertains to tax advice. Major firms that manufacture and distribute products have long since established standard disclosures for their sales agents to affirm that they do not provide tax, legal, or accounting advice, as those firms recognize that they are not acting in those capacities and do not want to be subject to the standards of care that would otherwise be required when providing advice in those domains. While they might not want to, there is no apparent reason that they can't separate out "financial" advice as a service capacity they are not engaging in, similar to the tax, legal, and accounting advice capacities they are clearly able to delineate… especially given their own statements in court that they are substantively not in the business of providing advice in the first place.

The key point, though, is simply that the Salesperson's Exemption serves to maintain choice for consumers – between sales and advice – without impinging on the existing business model and practices of the industry's product manufacturers and distributors. Instead, those organizations could rely upon the Salesperson's Exemption to avoid being subject to the Retirement Security Rule, in a manner that is consistent with their own prior legal briefs that "Brokers may provide some financial advice when assisting investors with a sale… this by itself does not convert them into an adviser – much less a fiduciary", and "Relationships that lacked that special degree of 'trust and confidence' – such as everyday business interactions – were long-recognized as non-fiduciary. For this and other reasons, a person acting as a broker ordinarily is not a fiduciary" and similarly that "an agent who receives a commission on the sale of a product is not paid for 'render[ing] investment advice.' She is paid for effecting the sale".

Impact On Access To Advice

When the Department's prior fiduciary rule was finalized, the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association ("SIFMA") claimed that the new rule would "curtail small-balance retirement savers' access to financial advice", the Financial Services Institute stated that they would be scrutinizing the rule on behalf of their broker-dealer members about whether it would preserve "access to affordable, objective financial advice delivered by their chosen financial advisor", and the Chamber of Commerce issued a study entitled "The Data Is In" highlighting how broker-dealers would likely pull back from small investors, resulting in a loss of access to advice. Similarly, in its re-proposal in the form of the Retirement Security Rule, those organizations again highlighted "its potential negative impact on Main Street Americans' access to financial advice", and declared that the new rule will "needlessly cause millions of lower- and middle-income workers to lose access to the financial advice", and that the new rule "could limit access to advice and education while also limiting investor choice in advisors".

Yet, as noted earlier, the Department's prior fiduciary rule was vacated by the Fifth Circuit on the basis that it would be inappropriate for the DoL to apply a fiduciary framework to salespeople who are not actually in an advice relationship of trust and confidence with consumers. As these very same industry associations representing product manufacturers and distributors, including the Financial Services Institute (FSI), the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA), and the Insured Retirement Institute (IRI), highlighted in their joint briefs with the Chamber of Commerce, they are salespeople, not in advice relationships of trust and confidence in the first place. And the Fifth Circuit agreed, stating with respect to those industry product manufacturers and distributors that "it is ordinarily inconceivable that financial salespeople or insurance agents will have an intimate relationship of trust and confidence with prospective purchasers".

Which means, simply put, consumers can't lose access to advice from organizations that by those organization's own admissions in court were never actually providing advice in the first place.

Instead, we believe that the industry actually has an advice-provider gap – that once the representatives of sales organizations are properly recategorized as salespeople, the actual number of advice-providers is painfully small and faces a severe talent shortage. For instance, the number of CFP certificants who are trained to provide comprehensive advisory services is just shy of 100,000. Even if each CFP practitioner serves 100 to 200 client households over their career, the advice capacity adds up to a range of only 10 million to 20 million households, a small fraction of the more than 120 million households in the U.S.

So why aren't more people attracted to the advice business, given the apparent consumer demand for advice? We believe that one of the biggest drivers is the broad base of salespeople who also market themselves as advisors, creating an uneven playing field for fiduciary advisors, which drives up the costs of and effectively crowding out the ability of actual advisers to market actual advice services to consumers.

For instance, a recent Kitces Research study on "How Financial Planners Actually Market Their Services" found that the typical advice-provider incurs a client acquisition cost of $2,167 in sales and marketing expenses to attract a single new client, and the cost rises to $4,056 per client amongst experienced advisors (whose time is more costly to engage in marketing and sales efforts). For an advice-provider who charges a 'reasonable' professional fee that may start at $250 per hour, it simply isn't economically feasible to engage a small investor for an hour or 2 of meaningful advice – not because they can't be serviced cost-effectively at that price point, but because advice-providers can't out-market sales organizations selling products under the guise of advice at that price point.

For example, the typical advice provider offers a full "comprehensive financial plan" for an average fee of $3,000 or implements a minimum account size of $300,000 (which, at a 1% AUM fee, amounts to a similar dollar amount). This effectively allows the typical advisor to earn a small profit ($3,000 of revenue on a $2,167 acquisition cost) to service a client.

By contrast, a salesperson who sells a commissionable product with a 5% upfront sales charge might earn $15,000 from the same $300,000 client, generating more than 5 times the revenue of an advice-provider, for what may amount to little more than the time it takes to fill out the application (less than an hour of actual advice and service). From the salesperson's perspective, making so much money on a single 1-hour transactional meeting is 'necessary' to compensate for all the other sales and marketing efforts to sell the product that were not successful – from networking meetings with other professionals to 'approach' meetings with prospects to seminar marketing efforts or even cold-calling.

But when a salesperson can earn 5 times the fee from a consumer for an "advice" relationship (that really is not) while providing substantially fewer benefits (since the engagement does not actually require the delivery of advice or the development of a financial plan), actual advice-providers cannot afford to compete. In other words, the lucrative nature of transactional sales on a per-transaction basis bids up the cost of client acquisition to the point that actual advice-providers cannot afford the marketing efforts necessary to attract their own clients and fulfill the need by retirement investors for objective recommendations.

This phenomenon is not unique to financial services, though. In his seminal paper, "The Market For Lemons: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism", George Akerlof demonstrated that in markets where consumers may have significant information asymmetry (i.e., they lack the knowledge to be able to identify who is a quality provider or not), low-quality providers can earn outsized profits by selling high-cost low-quality goods, and use the profits to out-market high-quality competitors, eventually driving high-quality providers away and resulting in market domination by low-quality providers in a proverbial race-to-the-bottom. Akerlof's research pertained to how this phenomenon was manifest in the used car market, where low-quality providers earned outsized profits by selling "lemons" while high-quality providers selling "peaches" could not survive. 5 years after the research was published, the United States enacted "Lemon Laws" to lift standards, automobile quality for consumers improved, and Akerlof won a Nobel prize for the applicability of his work to an ever-widening range of industries.

Accordingly, recognizing that the greatest barrier to expanding access to small investors (and attracting more advisors to serve them) is bringing down the extraordinarily high costs that advice-providers face in marketing their services against salespeople operating under the guise of advice, we believe that the Salesperson's Exemption, and more generally regulatory efforts to more clearly delineate sales from advice (applying high fiduciary standards of care to advice-providers but only to advice-providers), can actually lower the cost of advice and expand access by creating better clarity in the marketplace and reducing marketing costs for actual advisors who would no longer need to overcome competing sales pitches.

In fact, it's notable that since 2014, when the XY Planning Network was founded, the organization has quickly grown to more than 1,800 financial advisors offering advice services with no asset minimums and no product sales (operating instead on a fee-for-service basis, typically either for an hourly, project, or ongoing subscription fee). In turn, every advisor at XY Planning Network must not only be a fee-only advisor registered as an investment adviser and subject to a fiduciary standard, but members must also additionally sign and publish a "fiduciary oath" to further affirm their fiduciary obligation to clients.

Within XYPN, the majority of members access their Errors & Omissions (E&O) insurance – to protect against the liabilities that come from such standards of care for their advice – through XYPN itself. And in practice, with more than 1,000 of its advisor members on the XYPN E&O policy, there has collectively been only 1 insurance claim in the organization's history. And that claim was ironically for a trading error pertaining to a client who actually was also receiving investment management (not for the advisor's actual financial advice). Which means, notwithstanding the claims of product manufacturers and distributors of the high liability costs associated with fiduciary advice, XYPN's actual experience in the marketplace has been an ultra-low rate of liability associated with financial advice, to the point that XYPN's fiduciary advisors enjoy a lower-than-average cost of liability insurance because insurance underwriters – who have to put their money where their mouth is – have found that high-quality fiduciary advice actually has so little liability exposure in practice.

Separating Sales From Advice Preserves Choice, Reduces Costs, And Expands Access To Advice

More than 80 years ago, Congress recognized the important and distinct nature of advice relationships of trust and confidence and enacted the Advisers Act into law specifically to separate bona fide "investment counselors" providing advice from the salespeople at brokerage firms. Similarly, when Congress enacted ERISA, it again recognized the special nature of advice relationships of trust and confidence, appropriately applying a higher standard of care in situations where retirement investors are relying upon their investment fiduciary's advice.

The practical challenge, however, is determining when a sales relationship ends and an advice relationship begins, driven in no small part by a longstanding history and tendency of sales organizations to co-opt advice titles and advice-like services in order to sell their products – as recognized by the Advisers Act and ERISA – that sought to create dividing lines of when a relationship is actually an advice relationship.

As the sales and advice channels of the industry have again converged in recent years, we believe it is again time to re-assert a clearer bright line distinction between sales and advice, and that by creating a better separation between sales and advice, akin to Congress' approach in the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, and the SEC's more modest approach in Regulation Best Interest, the Department is actually prescribing a more protective panoply of protection for retirement investors. Separating sales and advice preserves a consumer's choice to each, does not impinge on industry business models pertaining to each, and is consistent with the Fifth Circuit decision that similarly arrived at the same conclusion.

As such, we agree that, conceptually, regulators should not apply a fiduciary advice standard to salespersons, and that concept can be applied in practice via a relatively straightforward "truth-in-advertising" approach that simply requires those who market themselves as acting in a position of trust and confidence to retirement investors be held accountable as such, and for those who wish to avoid fiduciary accountability be equally clear that they are not acting in an advice capacity.

We believe that, within the purview of ERISA and the Department's statutory authority, the best way to address this complex and controversial issue is promulgation of a Salesperson's Exemption as a new PTE that would become a key component of the Proposal, to more clearly delineate that an updated definition of an investment advice fiduciary applies to advice providers in relationships of trust and confidence and not to salespeople.

In the process, the Department can create greater clarity for retirement investors who have been documented through numerous independent studies demonstrating a remarkable capacity to trust their 'advisor,' based solely on the use of titles and related marketing practices. The end result is that when sales are more clearly separated from advice, actual advice-providers can more effectively market their services to retirement investors, bringing down the cost of advice and expanding access to advice for small retirement investors in particular.

XYPN appreciates the opportunity to provide feedback on the issues discussed above and welcomes any questions.

Leave a Reply