Executive Summary

In the United States, Registered Investment Advisers (RIAs) are required to register in one of 2 ways: with the Federal government (namely the SEC) or with one (or more) state securities regulatory agencies. While SEC-registered RIAs are governed by the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (and its associated regulations), state-registered RIAs are subject to the individual rules of the states (which have their own securities laws and regulations) where they are registered. So RIAs not only face a different set of regulations depending on whether they are Federally or state-registered, but state-registered RIAs, in particular, can also face a widely varying set of rules depending on which state they are registered in.

In this guest post, Chris Stanley, investment management attorney and Founding Principal of Beach Street Legal, breaks down some of the key differences between the Federal and state registration application requirements, approval processes, and post-registration requirements for RIAs.

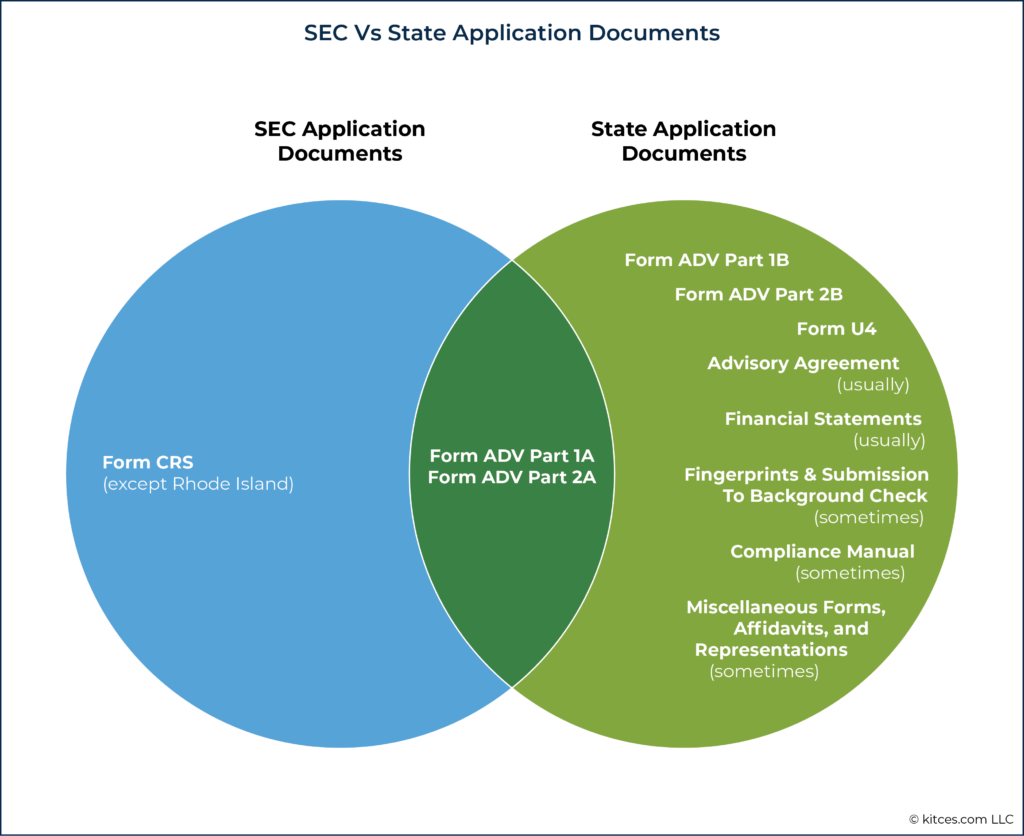

While there is some overlap between the specific documents to be submitted for those registering with the SEC as opposed to the states, the universe of documents is far from identical. To start, Form ADV is the foundational registration document that must be submitted by any advisor seeking to become registered with the SEC or the states, but submission requirements for its various sub-parts vary depending on the registration type. For instance, while firms applying for either SEC or state registration are required to submit Form ADV Part 2A (the brochure and wrap fee program brochure), Form ADV Part 2B (the brochure supplement) is required to be submitted only by state-registration applicants (though SEC applicants are still required to create, maintain and deliver a brochure supplement to clients). Notably, along with certain standardized forms (e.g., Form ADV and Form U4), state-registration applicants are almost always required to submit additional ancillary documents to the state(s) in which they are seeking registration as part of their application.

In addition to differing registration form requirements, firms applying for SEC or state registration typically will have different experiences in the approval process. For example, while the SEC is required to respond to an adviser’s application within 45 days of the initial filing date, state applicants can expect more variable and longer lead times during the registration process. Further, while the SEC’s review process usually tends to be straightforward and permissive, some states will respond with additional questions, follow-up requests, and required revisions to the contents of the documents submitted.

Once an adviser’s registration application has been approved, they can begin advice-rendering activities, but their regulatory obligations do not end there. Along with renewing their registration annually (for both SEC- and state-registered firms), firms face a variety of requirements related to their internal finances, fees, marketing activities, and advisor agreements depending on whether they are SEC- or state-registered.

Ultimately, the key point is that while both the SEC and individual states share the goal of protecting the public from financial predators, advisers typically face differing registration, approval, and ongoing supervision experiences, depending on how they are registered. But by being aware of the varying requirements and filing documents in an accurate and timely manner, new firms can navigate their way through the registration process and (finally) begin offering planning services to clients!

Navigating an adviser’s registration and notice filing decision matrix can be challenging enough given the duality of state and Federal regulatory regimes described in Part 1 of this two-part article series. But, as this Part 2 will underscore, registration and notice filing determinations are only the tip of the Federalism iceberg. From the moment an adviser embarks on the actual registration process itself, and throughout an adviser’s registration tenure, the real-world experience of an adviser will continue to diverge based on whether the adviser is registering with the SEC or with one or more states.

Federal Vs State Registration Application Differences For RIAs

In order to become registered as an investment adviser, both the SEC and the states require certain documents to be submitted through the Investment Adviser Registration Depository (IARD). While there is certainly overlap between the specific documents to be submitted to the SEC as opposed to the states, the universe of documents is far from identical.

Parts Of Form ADV For RIAs

Form ADV is the foundational registration document that must be submitted by any investment adviser seeking to become registered with the SEC or the states. The term “Form ADV” is actually an umbrella term that encompasses four sub-parts:

- Part 1 (not deemed worthy of a nickname)

- Part 2A (aka the “Brochure”) and/or Part 2A Appendix 1 (aka the “Wrap Fee Program Brochure”)

- Part 2B (aka the “Brochure Supplement”)

- Part 3 (aka “Form CRS” or the “Relationship Summary”)

Each part, in turn, is comprised of multiple sub-parts, items, schedules, Disclosure Reporting Pages (DRPs), and, with respect to the Brochure, a potential appendix. Some Form ADV parts, sub-parts, items, schedules, DRPs, and its potential appendix are required to be submitted solely by SEC-registered advisers, some are required to be submitted solely by state-registered advisers, and some are required to be submitted by both SEC and state-registered advisers. For a glossary of terms used throughout the Form ADV, refer to this Appendix C to Form ADV.

Form ADV Part 1

Both state- and Federal-registered advisers are required to submit Form ADV Part 1, which is largely comprised of boxes to check, radio buttons to select, and form fields to complete. It is effectively a statistical and demographic data gathering form that, unlike the other parts of the Form ADV, does not generally require any narrative (explanatory written) responses.

Part 1A of Form ADV Part 1 (classic government nomenclature, which is not confusing at all) applies equally to SEC and state-registration applicants. However, not all items of Form ADV Part 1A are to be completed by state-registration applicants. Item 2, for example, asks SEC-registration applicants to select the basis upon which the applicant is eligible for SEC registration (see Part 1 of this article for the list of SEC eligibility options). There is no equivalent eligibility question applicable to state-registration applicants.

Part 1B of Form ADV Part 1 is required only of state-registration applicants and asks for additional information regarding bond/capital information (if applicable), other (i.e., “outside”) business activities, financial planning services, custody, and information specific to sole proprietorships. State-registration applicants are also required to respond to additional DRPs regarding bonds, judgments/liens, arbitrations, and civil judicial actions.

When initiating the registration application process through the IARD system online, the first question the IARD system prompts an applicant to answer is whether it is seeking registration with the SEC or one or more states. Based on the response, the IARD system will generate a specific version of the Form ADV Part 1 for the applicant to complete such that inapplicable sub-parts and items generally will not be included.

The Brochure And Wrap Fee Program Brochure – Form ADV Part 2A

Like the Form ADV Part 1, both state- and SEC-registered advisers are required to submit Form ADV Part 2A, otherwise known as the Brochure. Unlike Part 1, the Brochure is entirely narrative (i.e., written out by the RIA in paragraphs to explain the key information in a readable format) and must be uploaded to the IARD system in a text-searchable PDF format. If the adviser sponsors a wrap fee program (i.e., generally, a program in which brokerage transaction charges are bundled or ‘wrapped’ with an adviser’s advisory fee into a single consolidated fee), the adviser must also submit a Wrap Fee Program Brochure. The Brochure and Wrap Fee Program Brochure are largely focused on the adviser itself, and not necessarily the individuals associated with the adviser.

Also like the Part 1, the contents of the Brochure will differ based on whether the applicant is seeking SEC or state registration. Specifically, Item 19 of the Brochure and Item 10 of the Wrap Fee Program Brochure are only required of state-registration applicants, and include additional information about the formal education and business background of principal executive officers and management persons, other business activities, performance-based fees, arbitration actions, legal proceedings, and relationships with issuers of securities.

The Brochure Supplement – Form ADV Part 2B

The Brochure Supplement is the sister disclosure document to the Brochure. Instead of focusing on the adviser itself, though, the Brochure Supplement focuses on the individual supervised persons of the adviser that 1) formulate investment advice for clients and have direct client contact, or 2) have discretionary authority over client assets, even if they have no direct client contact.

Importantly, both SEC-registered and state-registered investment advisers must create, maintain, and deliver a Brochure Supplement to clients; however, the Brochure Supplement need only be submitted through the IARD system for state-registration applicants and not for SEC-registration applicants.

Like the Brochure (Part 2A), the Brochure Supplement (Part 2B) has one additional section (Item 7) that is solely applicable to state-registration applicants. This section imposes additional disclosure requirements with respect to arbitration actions, legal proceedings, and bankruptcy petitions.

The Client Relationship Summary (CRS) – Form ADV Part 3

The Client Relationship Summary (also known as “Form CRS”) is only applicable to SEC-registration applicants that serve retail investors (with the odd exception of advisers seeking state registration in Rhode Island) and is also a wholly-narrative document to be uploaded to the IARD system in a text-searchable PDF format. The Relationship Summary does not contemplate any differences applicable to SEC versus state applicants, and was implemented as part of Regulation Best Interest in 2020.

Form U4

Form U4 (aka the Uniform Application for Securities Industry Registration or Transfer) is used to establish an individual’s registration with applicable states as an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) of a registered investment adviser (i.e., the IAR individuals who work for the RIA firm), and applies regardless of whether the IAR works for an SEC- or state-registered investment adviser. Notably, this same form is also used in connection with the registration of registered representatives of broker-dealers, which means that certain sections of Form U4 are inapplicable to those individuals that are registered solely as IARs and not also as registered representatives. However, as between IARs of state-registered advisers and SEC-registered advisers, the Form U4 requires effectively the same questions to be answered.

As further explained in Part 1 of this article, neither the Advisers Act (i.e., Investment Advisers Act of 1940, which applies to SEC-registered advisers) nor the rules promulgated thereunder impose any registration obligations upon individual representatives of advisers, regardless of what activities and functions they perform. The Federal registration regime does not bifurcate or distinguish between investment advisers and their representatives. Thus, all else being equal, the SEC will approve the registration application of an investment adviser without requiring the adviser to file a Form U4 for at least one IAR.

This is not to say that an SEC-registered adviser need not register any of its IARs at the state level (again, see Part 1 of this article), but simply that the Form U4 and IAR registration of an adviser of the firm is not a prerequisite for SEC registration approval.

An adviser’s registration approval in a state, however, is generally contingent upon the filing of a Form U4 for at least one IAR. In other words, even if a state-registration applicant has fully satisfied all application requirements via the Form ADV and the other ancillary documents described in the section below, a state will generally not approve an adviser’s registration unless one IAR is also registered in such state to be the individual adviser for/representing that RIA firm to clients (typically the adviser founder/owner).

Other Documents & Requirements For RIA Registration

State-registration applicants are almost always required to submit additional ancillary documents to the state(s) in which they are seeking registration as part of their application. Applicants typically email or mail such documents directly to the state securities authority; they are not submitted through the IARD system.

The specific ancillary documents to be submitted to a particular state can vary widely, as each state ultimately sets its own rules for RIAs registering in their state. Most states will want to see a copy of the adviser’s advisory agreement(s) and financial statements (typically at least a balance sheet and potentially an income statement as well), but beyond that your mileage will vary. Examples of additional ancillary documents that at least some states may require include:

- Attestation with respect to pre-registration activity of the adviser and its individual representatives.

- Background-check results directly submitted by a third-party fingerprinting or background-investigation vendor.

- Compliance policies and procedures manual.

- Financial-records-disclosure authorization form.

- Net capital worksheet.

- Surety bond.

- Verification of US citizenship.

- Statement regarding an individual representative’s obligations with respect to child support.

The above list is far from exhaustive, and it’s not uncommon for states to impose rather nitpicky formatting requirements, accompanying language in the form of sworn oaths, or even notarization requirements. State-registration applicants are encouraged to visit the website(s) of the applicable state(s) for further information (though brace yourself for a potentially infuriating experience… I’m pretty sure some state websites are still based on Geocities!).

The Registration Approval Experience For New RIAs

Section 203(c)(2) of the Advisers Act statutorily requires the SEC to either approve or institute proceedings to deny an adviser’s application for registration within 45 days of the initial filing date of the application. Compared to the state registration approval process, the SEC’s process is usually predictable, straightforward, and permissive. To quote Section 203(c)(2) of the Advisers Act:

The Commission shall grant such registration if the Commission finds that the requirements of this section are satisfied and that the applicant is not prohibited from registering as an investment adviser under section 203A. The Commission shall deny such registration if it does not make such a finding or if it finds that if the applicant were so registered, its registration would be subject to suspension or revocation under subsection (e) of this section.

Thus, within 45 days of submitting the Form ADV Part 1 and Brochure (and, if serving retail investors, the Relationship Summary), the SEC will generally approve the application for registration (or “deem the registration effective,” to use the SEC’s parlance) unless there is a fundamental deficiency related to the materials submitted, the adviser is not in fact eligible to register with the SEC, or the applicant would otherwise be subject to censure, activity limitations, suspension, or revocation.

During the registration application process, the SEC staff generally does not critique or wordsmith the ADV Part 1, the Brochure, or, if applicable, the Relationship Summary; the deep dive review is effectively deferred until the adviser’s first SEC audit (which may come as early as a few months after the initial registration date, or as late as several years after the initial registration date) during which examiners review the RIA’s business and compliance practices.

The registration approval process at the state level, however, is another story entirely, and can vary dramatically by state. Some states can take weeks, if not months, to pore over each document submitted and respond in the form of an initial deficiency letter with a litany of additional questions, follow-up requests, and required revisions to the contents of the documents submitted. The ball is then in the applicant’s court to either make the revisions noted and re-submit for review, or to push back and argue against deficiencies believed to be erroneous or unreasonable.

From there, it can sometimes seem like a veritable game of ping pong as the applicant and the state go back and forth until the state is satisfied that the application materials are to its liking. Applicants to states that require fingerprints to be submitted should be prepared to jump through a few additional hoops as well.

During this process, some states are responsive, helpful, and genuinely trying to facilitate new, duly qualified advisers to do business in their state. Others… less so. I’ve personally been involved with state registration applications that have been approved within 24 hours of submission, and others that have dragged on for six months. State turnaround times can ebb and flow based on the volume of applications received, the staff available to review such applications, and other seasonal variations.

Unlike the SEC’s statutory time limit of 45 days to approve or institute proceedings to deny an application, some states are not statutorily time bound and will respond to application submissions and re-submissions when they’re good and ready. I know of at least one state that is statutorily required to respond to applications within a certain timeframe, but essentially requires adviser applicants to sign a waiver to indefinitely extend the time afforded to the state to respond.

To be fair, state governments are rarely well funded, and can be understaffed relative to their investment adviser population. The job of state application review staff is to protect their constituents from financial predators and scam artists, and to serve an important gatekeeping function that should not be undervalued.

Furthermore, the burden imposed on state application review staff is heavier by design, since states will almost always respond to an adviser’s application with a letter that identifies deficiencies to be remedied, follow-up questions to be answered, and additional information to supply (while the SEC staff tasked with registration application reviews typically defers that work to the Division of Examinations that engages at a later date).

The takeaway is that state-registration applicants should expect more variable and longer lead times during the registration application process than SEC-registration applicants, who can typically expect their registration to be deemed effective within 45 days of application submission.

Federal Vs State Post-Registration Differences

Once an adviser’s registration application has been approved, the adviser and its duly licensed personnel are permitted to engage in the client solicitation and advice-rendering activities that were previously off-limits during the pre-registration phase. SEC-registered advisers are thereafter subject to the Advisers Act and the rules promulgated thereunder, and state-registered advisers are thereafter subject to the securities act(s) and rules respectively promulgated thereunder of the state(s) in which it is registered.

The registrations of both SEC- and state-registered advisers expire at the end of each calendar year unless renewed as part of the annual registration renewal process, which generally kicks-off in October or November of each year. As long as the adviser continues to timely renew its registration before the end of each calendar year (and assuming the SEC or a state does not earlier terminate the adviser’s registration due to a failure to remain eligible for registration or as a result of a disciplinary action), the adviser’s registration will remain in effect until voluntarily withdrawn by the adviser.

The regulatory obligations to which an adviser will be subject during this period of registration will vary based on whether the adviser is registered with the SEC or registered with one or more states. Below are a few examples.

RIA Financial Requirements

The SEC doesn’t have a prescriptive statutory requirement that obligates an adviser to maintain a certain minimum net worth, post a surety bond, or submit annual financial statements. Though Section 203(c)(1)(D) of the Advisers Act contemplates the possible adoption of a rule that requires the submission of a balance sheet certified by an independent public accountant and “other financial statements,” the SEC has to-date not adopted such a rule.

SEC-registered advisers are still required to maintain certain financial records for inspection by SEC staff during the course of an examination (such as a cash receipts and disbursements journal; general and auxiliary ledgers reflecting asset, liability, reserve, capital, income, and expense accounts; checkbooks; bank statements; canceled checks and cash reconciliations; bills or statements – paid or unpaid – relating to the business; trial balances; and internal audit working papers), but they generally need not submit any financial statements either in connection with the initial registration application or on a recurring basis thereafter.

There are two exceptions to this general rule as described in Item 18 of the Brochure: an adviser that requires or solicits prepayment of more than $1,200 in fees per client, 6 months or more in advance, is required to include an audited balance sheet prepared in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) as part of Item 18 of its Brochure. This is why most advisers do not collect more than $1,200 in fees per client, 6 months or more in advance, so as to avoid the requirement to prepare and publicly report their balance sheet.

In addition, an adviser that has discretionary authority or custody of client funds or securities, or that requires or solicits prepayment of more than $1,200 in fees per client, 6 months or more in advance, must disclose any financial condition that is reasonably likely to impair its ability to meet contractual commitments to clients.

Thus, if an adviser with custody, discretionary authority, or that imposes certain client pre-payment obligations is in such dire financial straits that it may not have the ability to fulfill the services it has agreed to deliver to clients in its advisory agreement, it is required to disclose this fact in Item 18 of its Brochure.

State-registered advisers can generally replace “$1,200” in the exceptions above with “$500”, as the balance sheet and financial disclosure obligation dollar threshold is lower for state-registered advisers (with at least the exception of Nebraska, which follows the $1,200 threshold instead).

Additionally, state-registered advisers are often subject to some combination of requirements that impose an ongoing minimum net worth, surety bond, and/or financial reporting requirement. Specifics will vary from state to state as expected, but most states impose more stringent requirements if the adviser has discretion and/or custody of client funds or securities.

NASAA Model Rule 202(d)-1, for example, generally pegs the minimum net worth threshold at $35,000 for advisers with custody, $10,000 for advisers with discretion over client funds or securities, and $0 (i.e., not negative) for advisers that accept prepayment of more than $500 per client, 6 or more months in advance. These tiers are commonly found in actual state securities rules (as many, albeit not all, states have implemented the aforementioned Model Rule).

Practically speaking, this means that most state-registered advisers – especially those with discretion and/or custody of client funds or securities – must be prepared to demonstrate compliance with such requirements both at the time of initial application and for so long as they are state-registered. Falling below a state’s minimum net worth threshold will likely trigger an immediate reporting obligation to the state securities authority, and failure to do so will likely have consequences if discovered during the course of an examination.

It is for these reasons that all advisers – but especially those that are state-registered – stay on top of the financial health of their businesses and ensure that their balance sheets remain current. It should also be noted that, at least for state-registered advisers, financial statements must typically be prepared in accordance with GAAP. This means that financial statements must be maintained on an accrual basis and not on a cash basis, and that advisory fees paid in advance should not be recorded as fully earned income at the beginning of the billing period (it should instead initially be recorded as unearned income, and then transferred to earned income at the end of the billing period).

Bottom line: check with your tax professional or CPA with respect to the maintenance and presentation of your financial records, especially if required to maintain/present such records in accordance with GAAP.

RIA Fee Itemization And Surprise Custody Audits

Both SEC and state-registered advisers with custody over client funds or securities are generally required to undergo an independent verification of client assets on an annual basis as performed on a surprise basis by an independent certified public accountant (colloquially referred to as the “annual surprise exam”). However, if an adviser is deemed to have custody of client funds or securities solely as a consequence of its authority to make withdrawals from client accounts to pay its advisory fee (i.e., fee deduction authority), it can avoid the annual surprise exam.

For SEC-registered advisers, the analysis effectively stops there, as there are no conditions imposed on the annual surprise exam carve-out if custody is only triggered by fee deduction authority (so long as the adviser is otherwise in compliance with the custody rule).

However, for state-registered advisers, the ability to avoid the annual surprise exam is usually conditioned on the adviser jumping through three additional hoops as described in NASAA Model Rule 102(e)(1)-1:

- The adviser must have written authorization from the client to deduct advisory fees from the account held with the qualified custodian;

- Each time a fee is directly deducted from a client account, the adviser concurrently:

- Sends the qualified custodian an invoice or statement of the fee to be deducted from the client’s account; and

- Sends the client an invoice or statement itemizing the fee. Itemization includes the formula used to calculate the fee, the amount of assets under management the fee is based on, and the time period covered by the fee.

- The adviser discloses its compliance with these conditions in its Brochure.

The first and the third condition described above are fairly non-controversial, but the fee itemization condition can sometimes be tricky to accomplish without third-party advisory fee billing software.

There is no equivalent fee itemization requirement in the SEC’s custody rule, which means that SEC-registered advisers are not subject to the additional conditions described above.

RIA Marketing Activities (Including Testimonials)

Yours truly has already written – at excruciating length – about the SEC’s (new) Marketing Rule and the fact that it now permits the use of client testimonials in SEC-registered adviser advertisements.

The states, on the other hand, fall into one of three categories:

- Those that still explicitly prohibit client testimonials in advertisements;

- Those that defer to the SEC’s Marketing Rule (and therefore permit client testimonials in advertisements); and

- Those that have rules that do not specifically prohibit testimonials and do not specifically defer to the SEC’s Marketing Rule.

The first two categories of states are the most common, as they track the two alternative provisions contained in NASAA Model Rule 102(a)(4)-1 (which enumerates unethical business practices of investment advisers and their representatives).

For a state-registered adviser registered in multiple states – some of which prohibit testimonials and some of which do not – this has the practical effect of imposing the lowest common denominator of regulation (i.e., the most restrictive state’s rules) on such an adviser and therefore making the utilization of client testimonials de facto prohibited.

Unless the adviser can segment its advertising on a state-by-state basis (such that advertisements containing client testimonials only appear within states that permit the use of testimonials), or solely operates in state(s) that permit testimonials, the testimonial permissibility in some states is of no use.

RIA Advisory Agreements

Yours truly has also already written at excruciating length about client advisory agreement requirements and best practices (see Part 1 and Part 2 of that recent article series), but a few state nuances are worth summarizing below:

- Many states prohibit advisers from accomplishing an assignment or modification of the advisory agreement via negative/passive consent, and instead require clients to affirmatively consent in writing to any assignment or modification of the advisory agreement in advance.

- Many states impose various restrictions with respect to dispute resolution clauses and may require that the choice of law be based on the client’s state of residence and the venue be a location most convenient for the client. Some even outright ban mandatory arbitration.

- Some states take a rather ‘creative’ position with respect to what constitutes an ‘unreasonable’ fee and may either explicitly or implicitly prohibit certain types of fee arrangements, especially with respect to flat or hourly fees for financial planning. At least two states have even been known to cap the hourly rate an adviser may charge.

- Some states (e.g., Washington and Maryland) require the re-submission of advisory agreements if they have been materially amended after the adviser is first registered.

- Some states construe any attempt by an adviser to limit its liability as an unethical business practice and ban such contractual attempts outright.

The SEC has also recently started to more heavily scrutinize liability limitation or ‘hedge’ clauses in advisory agreements, as evidenced by a recent settlement involving an investment adviser in January 2022, 2 recent SEC Risk Alerts (the January 2022 Private Fund Risk Alert and the November 2021 Electronic Investment Advice Risk Alert), and the 2019 SEC Interpretation Regarding Standard of Conduct for Investment Advisers.

However, on balance, the SEC is generally more permissible with respect to the content of advisory agreements, and – with the exception of the hedge clause skepticism referenced above – has not been known to prohibit the other above-referenced practices that some states have.

Other Notable Issues For Ongoing RIA Compliance (State Vs SEC)

In addition to the more material differences described in the preceding sections, there are a few other miscellaneous SEC versus state nuances that are worth mentioning, at least in brief:

- A few states (e.g., Illinois) require advisers with multiple places of business within the state to file a form and pay a fee for each such additional “branch office”. The concept of filing separate forms or paying separate fees for branch offices does not exist at the Federal level (though the SEC did recently publish a risk alert regarding the supervision expectations imposed on “advisers operating from numerous branch offices and with operations geographically dispersed from the adviser’s principal or main office”).

- The current SEC thresholds for determining whether a client is a “qualified client” (a key prerequisite for an adviser that charges performance fees) is currently $1.1 million under the management of the adviser or $2.2 million in net worth (excluding the value of the client’s principal residence). The dollar thresholds triggering qualified client status may differ in certain states, as the automatic inflationary adjustments made by the SEC do not automatically apply to the states. In other words, state securities rules may include a different definition of what constitutes a qualified client, and/or still be using ‘prior’ thresholds not in line with more recent SEC adjustments. This poses a potentially awkward scenario in that a particular client may be charged a performance fee while an adviser is state registered, but not if the adviser later transitions to SEC registration.

- Rule 204A-1 under the Advisers Act (the Federal act) requires SEC-registered advisers to establish, maintain, and enforce a written code of ethics that contains very specific and technical contents – including requirements related to the reporting and review of personal securities accounts of access persons. Not all state rules technically require a code of ethics or the reporting and review of personal securities accounts.

- A few states break from the norm in their interpretations of how certain questions to Form ADV should be answered. I’ve seen this borne out as described in the following sections (which reflect a non-exhaustive list of examples):

- Form ADV Part 1, Item 9(A), which addresses custody of client assets: SEC-registered advisers and most state-registered advisers can answer this question “no” if the sole reason they are deemed to have custody is due to client fee deduction authority. A handful of states require this question to be answered in the affirmative, even if the adviser is deemed to have custody solely due to their client fee deduction authority.

- Form ADV Part 1, Item 6 is intended to cover the other business activities (besides rendering investment advice) of the adviser, and Form ADV Part 1, Item 7 is intended to cover the adviser’s financial industry affiliations and activities (i.e., if a related person of the adviser engages in one of the enumerated activities). I’ve experienced a small number of states that seem to believe Item 7 covers other business activities of the firm as well (not just those of the adviser’s related persons).

- The states can differ dramatically in how broadly they construe the term “soft dollars” as referenced in Form ADV Part 1, Item 8(G), and Form ADV Part 2A, Item 12. Certain states take a very liberal interpretation of what constitutes soft dollars, and construe standard, off-the-shelf services provided by a custodian to all investment advisers to be soft dollars (e.g., a web-based advisor portal, educational webinars and whitepapers, etc.). Others more closely track the SEC’s more literal interpretation as found in the SEC’s 1998 Inspection Report on the Soft Dollar Practices of Broker-Dealers, Investment Advisers and Mutual Funds: “arrangements under which products or services other than execution of securities transactions are obtained by an adviser from or through a broker-dealer in exchange for the direction by the adviser of client brokerage transactions to the broker-dealer”.

While the voluminous pre- and post-registration requirements may seem intimidating at first, the good news is that the paths through state registration and SEC registration are well worn. Tens of thousands of investment advisers have successfully registered and thereafter maintained their registrations. If all of this is simply too much to digest alone, there are a host of compliance consulting firms, law firms, adviser membership organizations, and other vendors that stand ready to chart the path and lead the way through. State-registration applicants also have the opportunity – depending on their state – to directly engage with the person or person(s) responsible for reviewing and approving investment adviser applications to learn directly from the registration gatekeeper. Don’t be afraid to reach out.

With the right team and the right resources (which hopefully includes this article), investment advisers can confidently register, remain compliant, and focus on serving their clients.

Leave a Reply