Executive Summary

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) included the most substantial changes to the tax code that we have seen in over 30 years. The change which has garnered the most attention amongst financial advisors, though, is the new 20% deduction for Qualified Business Income (QBI). What's unique about the QBI deduction (also known as the IRC Section 199A deduction, or the pass-through deduction) is not just the size of the deduction (as a deduction of up to 20% of certain business income is certainly appealing!) but the fact that many financial advisors themselves will be eligible for a QBI deduction, albeit subject to some "high-income" limitations that some financial advisors will need to plan for in order to avoid having their QBI deduction phased-out entirely.

In this guest post, Jeffrey Levine of BluePrint Wealth Alliance, and our Director of Advisor Education for Kitces.com, examines how financial advisors (and other Specified Service Businesses) can maximize their QBI deduction through business entity selection, including why employee advisors may want to convert to being independent contractors, why S corps may want to convert to partnerships, LLCs, or a C corp (or not!), and why sole proprietors may not need to make any changes at all.

A key to understanding the new QBI deduction is how the "high-income" phaseout works. For QBI purposes, any Specified Service Business owner (including a financial advisor) who files a joint tax return with more than $315,000 of taxable income, or an individual who files under any other status with taxable income of more than $157,500, will be considered "high-income". And being "high-income" triggers a partial phaseout of the QBI deduction, and culminates in a total phaseout once taxable income exceeds $415,000 (joint) or $207,500 (other tax filers). Notably, since these thresholds are based on taxable income, it includes income from any sources (investment, spouse, etc.), even though the QBI deduction itself is calculated based on the business' income.

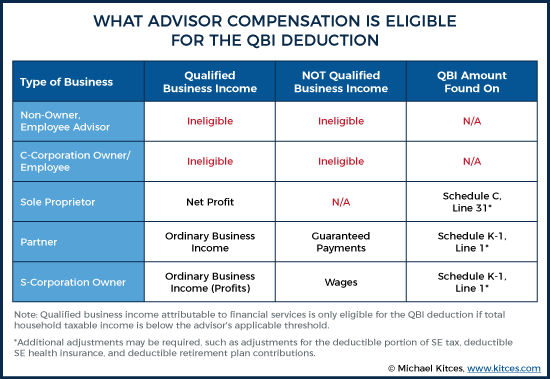

The reason business entity selection influences an advisor's QBI deduction is that not all compensation to an advisor (or other small business owner) is considered qualified business income eligible for the deduction in the first place. For instance, financial advisors who receive W-2 wages as an employee advisor are not eligible for a QBI deduction for those wages... which is why employee advisors may want to consider converting to become independent contractors (if their employer will allow it), as their sole proprietor income would be considered QBI. Income from partnerships or LLCs taxed as partnerships will generally be considered QBI, with the exception of guaranteed payments made to partners (which may mean advisors utilizing operating agreements with substantial guaranteed payments may want to reconsider this structure in light of QBI considerations). The good news for S corps is that so long as advisors can reasonably claim a lower salary, profit distributions (though not the wages portion) will avoid self-employment taxes and be considered QBI (although this extra incentive to push the boundary of what may be considered reasonable salary will also likely mean extra IRS scrutiny of S corp income). For C corp owners, wages again are not considered QBI, although such owners may still benefit from the newly reduced corporate tax rate of only 21%.

Ultimately, the key point is to acknowledge that business entity selection plays a key role in maximizing a QBI deduction as a specified service business owner (which includes financial advisors). And although many financial advisors (and other specified service business owners) may totally phase out the QBI deduction due to their high income, choosing the right business entity structure can help advisors preserve as much QBI deduction as possible!

How the QBI Deduction Impacts Financial Advisors (And Other Specified Service Businesses)

When the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was passed in late 2017, it made substantial changes to the tax code, the likes of which had not been seen for more than three decades. In the months since, advisors have been scrambling to understand those changes, assess their impacts, and implement and revise strategies to try and minimize the impact of taxes for their clients. Perhaps no single change or provision of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act though, has drawn more interest and created more buzz among planners than the new 20% deduction for qualified business income (QBI)… and for good reason.

The new QBI deduction, also known as the IRC Section 199A deduction, or the pass-through deduction, allows some business owners – a common target market within the advisor community – to take a deduction for up to 20% of certain business income on their personal returns. A deduction that large, alone, would draw many advisors’ interests, but what has really energized some is the veritable treasure trove of planning strategies that can be used to add value to clients by helping them maximize the deduction.

And the starting point is to make a good decision about what business entity to use in the first place. As while any type of “pass-through” business that is not a C corporation is eligible for the QBI deduction – including sole proprietorships that don’t even have a separate business entity – not all business entities are treated exactly the same. Which is actually relevant not only for the small business owner clients of advisors, but also of financial advisors themselves!

There is, of course, no single correct response to the ideal business entity to maximize the QBI deduction, and the correct answer will vary based upon an individual advisor’s unique set of circumstances, such as:

- Whether the advisor is an owner, or part owner, of their practice

- The entity type (i.e., S corporation, partnership, sole proprietorship) of the advisor’s practice

- The amount of the advisor’s compensation

- The type of compensation received by the advisor (i.e., salary, net profits, guaranteed payments)

- How compensation is being divided across advisors in multi-advisor (or more generally, multi-owner) practices

- The advisor’s own household filing status

- The advisor’s other household income (including, if applicable, their spouse’s income) and deductions

In other words, the financial advisor as a small business owner is actually a case-in-point example of proactive planning strategies for the IRC Section 199A QBI deduction in the first place, where choice of business entity can have a significant impact!

Financial Advisors Are Eligible for a QBI Deduction, But…

When determining the potential impact of the QBI deduction, the first step an advisor (or any small business owner) must take is to determine whether or not they are a “high-income advisor” In the first place. Because financial services is one of a group of businesses that is considered a “Specified Service Business” under the QBI rules, which means the QBI deduction is phased out at higher income levels.

Of course, that begs the question, “What defines a ‘high-income’ advisor?” for the purpose of the QBI deduction. Though the answer to the question of “what’s high income?” may vary depending upon who you ask, for QBI deduction purposes, a “high-income advisor” is any advisor who files a joint tax return and has more than $315,000 of taxable income, or an advisor who files using any other filing status and has taxable income of more than $157,500.

Note that because the above amounts are based on taxable income, they include not only the compensation received by an advisor from their advisory practice itself, but also income from any/all other sources, such as investment income, and a spouse’s income, and are reduced by all available deductions. Thus, for the purpose of analyzing eligibility for the QBI deduction, an advisor with $1 million of net profit from their sole proprietorship advisory practice, and an advisor with $10,000 of net profit from their sole proprietor advisory practice, but whose spouse earns $1 million, would both be “high-income advisors.” Thus, even though the QBI deduction itself is calculated based on the business’ income, the determination of “high-income” status is based on the individual’s (or household’s) personal tax return, including all income, and after all deductions.

While in general, many are, or aspire to be, a “high-income advisor,” when it comes to the QBI deduction, those advisors who don’t meet the definition are actually at an advantage… at least for income tax purposes. That’s because, again, those who exceed the taxable income thresholds will be partially or fully phased out of their QBI deduction, while advisors with taxable income below $315,000/$157,500 are eligible for a “full” QBI deduction. The “full” QBI deduction is calculated by multiplying 20% times the lesser of an advisor’s qualified business income, or the advisor’s total taxable income from all sources and after all deductions (less capital gains and qualified dividends, and prior to the application of the QBI deduction itself).

Yes, that’s right, despite what you may have heard, or even read, many financial advisors will still benefit from a full QBI deduction, despite being a Specified Service Business!

Example #1: Benny is a sole proprietor financial advisor and has net profits from his advisory practice of $125,000. Benny’s wife, Judy, is a W-2 employee and earns a salary of $75,000. Assuming Benny and Judy’s only deductions are the standard deduction ($24,000 in 2018) and the deduction for one-half of Benny’s self-employment taxes, their taxable income, prior to the application of the QBI deduction, would be $167,169. Since this amount ($167,169) is more than Benny’s net profits from self-employment ($125,000), the QBI deduction will be calculated by multiplying 20% times Benny’s net profit of $125,000. The result is a QBI deduction of $25,000, reducing the couple’s final taxable income to $142,169, and saving them just over $5,500 in Federal income tax at their 22% tax bracket.

Example #2: Alison is a sole proprietor financial advisor and has net profits from her advisory practice of $125,000. Alison’s husband, Frank, is a stay-at-home dad and Alison’s business income is their only income. Assuming Alison and Frank’s only deductions are the standard deduction and the deduction for one-half of Alison’s self-employment taxes, their taxable income, prior to the application of the QBI deduction, would be $92,169. Since this amount ($92,169) is less than Alison’s net profits from self-employment ($125,000), the QBI deduction will be limited to 20% of the couple’s taxable income of $92,169 (prior to the application of the QBI deduction itself), and not 20% of Alison’s total business income. This results in a QBI deduction of $18,434, reducing the couple’s final taxable income to $73,735, and still saving them over $4,000 in Federal income taxes.

Business Entities And Types Of (Advisor) Compensation Eligible As Qualified Business Income?

As the name of the deduction itself implies, the QBI deduction isn’t applicable to all income, only “qualified business income”.

Not all compensation to an advisor that is “income” from the business, however, is considered qualified business income in the first place. To determine whether or not an advisor’s income is QBI, it is necessary to consider the type of income received, and the type of entity from which it originated.

Non-Owner Employee (W-2) Financial Advisors

Non-owner employee financial advisors compensated with W-2 wages are not eligible for the QBI deduction at all (at least for their work and income as a financial advisor). Wages are not considered qualified business income, regardless of the type of entity from which those wages are paid.

However, some non-owner employee advisors employed by smaller planning firms may benefit from having a conversation with their employer and discussing the possibility of switching from W-2 employee advisor to independent contractor advisor who files as a sole proprietor (as there’s no actual requirement to have a “pass-through” business entity to receive the QBI deduction).

In some cases, such a change may benefit both parties, as the business owner avoids payroll tax obligations, while the employee-now-contractor advisor gains access to the QBI deduction. The tax benefits of any such change, however, must be carefully balanced with the loss of any employee benefits the advisor may have also been receiving, such as health insurance and retirement plan benefits, and compensation itself may have to be adjusted to account for the changes.

Example #3: Ryan is a single non-owner employee financial advisor. He earns a $100,000 W-2, has $20,000 in interest, and claims the standard deduction. Given these facts, Ryan would owe Federal income tax of $20,210 for 2018. In addition he’d also owe employment taxes on his salary of $7,650. As a result, Ryan would have total taxes of $27,860 on his total after-tax income of $92,140.

At the same time, Ryan’s employer would have its own costs associated with his employment. There’s the obvious cost associated with Ryan’s salary ($100,000), and then there’s the employment taxes on that amount of $7,650. Thus, the total cost to Ryan’s employer for his services comes to $107,650.

Suppose now, however, that Ryan and his employer come together to try and lower their mutual costs. After some quick calculations – Ryan is a financial advisor afterall! – Ryan and his employer come to an agreement that he will become an independent contractor, but will have his compensation increased to $104,000. As a result, Ryan’s total Federal income tax bill for 2018, including self-employment tax, would be $29,109, leaving him with $94,891 of after-tax income. That’s more than $2,500 in after-tax income than Ryan had as an employee!

But what about Ryan’s “employer?” Well, this truly is one of those win-win scenarios. As a result of transitioning Ryan from a W-2 employee to an independent contractor, the only cost is now the $104,000 of non-employee compensation paid. That’s more than a $3,500 savings for Ryan’s “employer” on top of the $2,500+ savings to Ryan, himself!

And there’s the potential for even more savings that can be shared when other factors are considered. This includes accounting for expenses that would be deductible by an independent contractor, but not an employee, for expenses that contractor/employee is already incurring, such as auto expenses, home office expenses, and the like.

Example #4: Karen is a single non-owner employee financial advisor. Like Ryan in the previous example, she earns a $100,000 W-2, has $20,000 in interest, and claims the standard deduction. Thus, she has the same total tax bill of $27,860 and after-tax income of $92,140. Similarly, the cost to Karen’s employer attributable to her services comes to $107,065 (the same as Ryan).

Imagine, though, that after reviewing their respective situations, Karen and her employer agree to transition Karen to an independent contractor, while simultaneously lowering her (non-employee) compensation to $95,000. Evaluated in a vacuum, you might be tempted to think “But why would Karen ever agree to that?” Planning, however, cannot – or at least should not – occur in a vacuum. So now suppose that Karen is able to reduce her net income from self-employment by $20,000 for certain items that she was previously unable to deduct as an employee, including certain auto expenses, meals with clients, and a home office.

The result for Karen is a Federal income tax bill for 2018, including self-employment tax of $20,331, leaving her with $74,669 in after-tax income (($75,000 net income from self-employment + $20,000 interest) - $20,331 = $74,669). That’s dramatically less than the $92,140 Karen had as an employee, which on the surface may not seem all that great. But remember, in this scenario, Karen actually was paid $95,000 in non-employee compensation. Her net income of $75,000 discounts the fact that the $20,000 difference between that amount and the gross amount received is due to expenses that Karen would have incurred anyway! Thus, compared to her initial employment engagement Karen still comes out ahead. Initially, she has $92,140 of after-tax dollars remaining to fund X (whatever “X” happens to be) amount of expenses, whereas now, Karen has $74,669 to cover X - $20,000 worth of expenses. Thus, Karen has a net benefit from her change in employment status of $2,529 (($74,669 + $20,000) - $92,140 = $2,529. Conversely, Karen’s former employer saves a whopping $12,065 due to not only the reduction in compensation paid to Karen, but the savings of employment taxes as well.

Perhaps, given the relatively lopsided outcome of this arrangement, Karen could negotiate a higher amount of non-employee compensation. If, however, she was unable to convince her “employer” to budge on the numbers, then even though she goes from paying only half of the employment taxes to all of the self-employment tax, and even though she’s actually paid less as an independent contractor than she was as an employee, by accepting this deal she would still end up with more spendable dollars. On the other hand, though, Karen would have to weigh this against any other employee benefits she might lose access to (e.g., employer-paid health insurance or retirement plan matching contributions).

Notably, although non-owner employee advisors working for large planning firms may benefit from the same potential change, it is far less likely that a large employer will create an exception or adjust its business model for a small number of employees. Thus, such advisors are likely to remain W-2 employees.

And of course, it’s important to bear in mind again that financial advisors whose household income exceeds the income thresholds for the Specified Service Business test will lose the QBI deduction anyway. Thus, even to the extent the employee advisor can switch to independent contractor status, with respect to the QBI deduction, it will have no net benefit for joint filers with household taxable income above $415,000, or any other advisors with income above $207,500, who are completely phased out of the QBI deduction (and may be partially phased out for those who are above $315,000 and $157,500, respectively).

Sole Proprietor Advisors

While some employee advisors may want to switch from being a W-2 wage employee to an independent contractor that files as a sole proprietor, most solo financial advisors are already sole proprietors, which means their net profits are QBI and eligible for the deduction (which they can claim as long as their household income remains below the income thresholds for the Specified Service Business test).

It is important to note that while many registered investment advisers and insurance professionals choose to operate as sole proprietors largely due to the simplicity it provides, brokers affiliated with broker/dealers are often organized as often operate as sole proprietors because they have little or no choice. Under FINRA rules, in general, commissions may only be paid to a licensed person of a broker-dealer, or a(nother) broker-dealer entity. Thus, while a licensed individual (i.e., someone with a Series 7, or Series 6 license) may be paid commissions directly for from a broker/dealer for investments sold, in order to have those commissions paid to an entity instead, that licensed individual would actually have to set up their own, properly licensed broker/dealer entity! Due to the capital requirements and other costs of running a broker-dealer, though, plus rising regulatory burdens, few brokers make this choice.

Which simply means that small RIAs and independent insurance agents often operate as sole proprietors, and brokers typically must operate as sole proprietors, making their net income from the sole proprietorship Qualified Business Income eligible for the QBI deduction.

Financial Advisor Partnership Income (or LLCs Taxed As A Partnership)

Small ensemble practices of advisors are often organized as partnerships, or as LLCs taxed as partnerships. Such entities are easily established, generally have fewer requirements than corporations, and perhaps most importantly for emerging practices, allow for operating agreements that can allocate and distribute profits disproportionately to the ownership of the entity (provided such arrangements have been agreed to via an operating agreement), whereas owners of corporations must receive profits (dividend distributions) of the corporation in proportion to their ownership of the entity.

The good news is that for QBI purposes, income received as a partner in advisory practice is generally considered QBI. However, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act included a specific carve-out from the QBI rules for guaranteed payments made to partners. Such amounts are not considered QBI, and thus, are not eligible to be included in the QBI deduction calculation.

Advisors engaged in partnerships that utilize operating agreements which require substantial amounts of guaranteed payments may wish to revisit their operating agreements and determine whether such guaranteed payments are still necessary and/or beneficial. As while guaranteed payments may be necessary to re-allocate certain profits of the business based on the respective owners’ contributions, they are explicitly less favorable from a QBI perspective.

Financial Advisor Employee/Owner Of S Corporations

A significant number of advisory practices are organized as S corporations. In particular, the structure is popular among solo-advisors operating insurance-based businesses, or as a Registered Investment Adviser, because the advisor can control the amount of salary they pay themselves. For single owner/employee S corporations, any net income, before owner compensation, that is not paid out as salary, is distributed (or is deemed distributed) to the owner in the form of profits. While both salary and profits from S corporations are taxable at ordinary income tax rates, only salary paid is subject to employment taxes.

Though IRS rules require that S Corporation owners, acting as employees, pay themselves a “reasonable” salary, the disparity between the tax treatments of salary vs. profit has long created the incentive S corporation owner/employees to make that “reasonable” salary as small possible. And now, that incentive is further exacerbated by the QBI deduction rules, because not only are the profits from S corporations able to avoid self-employment taxes, they are considered QBI (while wages are not).

Thus, the benefits of structuring an advisory firm as an S corporation are now even more substantial than before, to the extent that the advisor can reasonably pay themselves less than the full profits of the S corporation as salary in the first place and save on both self-employment taxes and gain the QBI deduction. At least as long as their total household income is below the income threshold to avoid having the QBI deduction disqualified under the Specified Service Business test.

On the other hand, while the tax incentive certainly exists to push the boundaries of reasonable compensation when it comes to S corporation owner/employees (even more so now for advisors who can claim the QBI deduction and are below the income threshold), advisors should be particularly sensitive to making sure they pay themselves truly reasonable wages. Although chances of an IRS examination are fairly low today, and when they do occur, such examinations are generally kept private, they can be time-consuming, expensive, and distract an advisor for more important matters. And the IRS will have more incentive than ever to investigate such matters, given that the additional QBI deduction benefit to the firm owner is now an additional tax collection opportunity for the IRS when catching business owners who aren’t paying themselves “reasonable compensation” salary!

Additionally, should an IRS examiner deem an S corporation owner/advisor’s salary to be unreasonable and the advisor seeks to challenge the IRS’s determination in court, it would become a public matter, potentially damaging the advisor’s reputation. At the very least, they might end up becoming a future case study. Just ask this financial advisor…

Financial Advisors Structured As C Corporation Owners

Some financial advisors, particularly owners of larger advisory businesses, are organized as C corporations. The QBI deduction does not apply to owners or employees of these businesses, because it does not apply to dividends received by C Corporation owners and, as noted above, wages are never considered QBI, regardless of the type of entity from which they are paid…

On the other hand, the whole point of the QBI deduction for pass-through businesses was, in large part to keep parity with the new, dramatically lower corporate tax rates. Which means that while financial advisors who are structured as C corporations won’t benefit from the QBI deduction, they may already be benefitting from the new reduced corporate tax rate of only 21%.

Business Entity Restructuring Decisions for Financial Advisors (And Other Specified Service Business Owners)

Determining the “best” entity structure for an advisor is often quite complex and requires consideration of far more than just the QBI deduction. Nevertheless, the significant impact that a change in entity type can have on the QBI deduction means that some advisors should revisit this decision now. When doing so, advisors should be sure to keep the following key issues in mind:

- A change from one entity type to another can be quite onerous. Furthermore, certain changes may be more difficult to “reverse” if the QBI deduction is eliminated or sunsets (as it is currently scheduled to do after 2025)

- A change in entity structure will only benefit advisors with taxable income below the upper-limit of their applicable QBI-deduction phaseout range. Higher income advisors will be phased out of the QBI deduction, regardless of entity type.

The following is a brief synopsis of the impact to the QBI deduction (and only the QBI deduction) for qualifying advisors (advisors with taxable income low enough to enjoy at least a partial QBI deduction) as a result of various changes in entity structure.

From Employee to Independent Contractor

As non-owners, employee advisors are not eligible for the QBI deduction (at least not for their work as an employee advisor). Since, however, financial services is a specified service business, there is no QBI-deduction-related incentive for owners to keep “employees” as true W-2 employees, as opposed to utilizing independent contractors (whereas with non-specified service businesses, the payment of W-2 wages can be an important factor of maximizing the QBI deduction). Thus, some employee advisors may benefit from discussions with their employer about switching to independent contractor status, in order to potentially receive a QBI deduction.

This change is most likely to occur with smaller businesses, where the switch from employee advisor to independent contractor would have a minimal impact on the underlying business model itself, as well as in situations where the employer can be enticed with potential shared savings, too (in particular, reduced payroll/FICA tax burdens, and reduced employee benefits obligations).

From Sole Proprietorship to Another Business Entity

Interestingly, while the sole proprietor business structure is the simplest form of business ownership, when it comes to the QBI deduction, it’s also generally the most efficient structure for owners of specified service businesses. Sole proprietor advisors are eligible for a QBI deduction on the full amount of the net income (the profit) generated by the business (though the QBI deduction can be limited if taxable income is less than the business profits).

By contrast, advisors in partnerships (or LLCs taxed as partnerships) may see some of their business income rendered ineligible for the QBI deduction because it’s received in the form of guaranteed payments. Similarly, advisors who are owner/employees of an S corporation can only receive a QBI deduction for the profits of the business, and not for the salary portion of their income.

As a result, most advisors who can and do already operate efficiently as sole proprietorships will likely want to stay that way (at least for the purpose of the QBI deduction).

From an S corporation to a Partnership (or LLC Taxed as a Partnership)

Of all the potential changes of entity structure an advisory practice may consider in light of the new QBI deduction, the switch from S corporation to partnership tax treatment may have the greatest appeal. While such a change may result in an increase of self-employment taxes, this increase in cost may be more than offset by the tax savings of turning QBI-deduction-ineligible W-2 wages into QBI-deduction-eligible partnership distributions.

Notably, it’s important to remember that for a partnership to exist, there must be more than one owner of the business. This isn't necessarily a problem for a multi-advisor business, but can present added complications to the desire to do the necessary work to make the change. The reason is that when it comes to the QBI deduction, not all owners may be eligible for (and therefore care about) the QBI deduction in the first place. In other words, when owners’ taxable incomes may vary dramatically, making some owners eligible for the QBI deduction but not others, some owners will have a financial incentive for a potential change in entity structure... but others will not.

Additionally, it should be noted that some S corporations use salaries to ensure total compensation to owner/employees is “fair”. In a partnership (or LLC taxed as a partnership), this can still be accomplished with guaranteed payments. However, the use of guaranteed payments in a partnership would diminish the value of the entity change at least for those partners receiving guaranteed payments – as such guaranteed payments are not considered qualified business income and are thus not eligible for the QBI deduction anyway. Which means a switch from S corporation to partnership or LLC will only be desirable if it's economically feasible to allow most of the profits of the business to flow out as actual profits of the business (and not as guaranteed payments to various owners).

From a (solo) S corporation to a Sole Proprietorship

Historically, some financial advisors have chosen the S corporation structure, even without having any other partners, simply as an effort to reduce FICA taxes by taking a portion of their income as wages and a portion of (non-FICA-taxed) "profits" instead.

While this strategy for FICA tax reduction remains available, though, it is somewhat less appealing in a world where splitting income into wages and profits eliminates FICA taxes on the "profits" portion, but eliminates the QBI deduction on the wages portion compared to just taking home all the income as sole proprietorship self-employment (QBI-eligible) income.

Ultimately, the relative value of this trade-off will depend on how much of the total business income is being taxed below the Social Security wage base (where the FICA tax savings on profits is a substantial 15.3% in taxes while the QBI rules are "only" a 20% deduction), versus how much wage income is being paid above the wage below (where the FICA tax savings is only 2.9%, and the full 20% QBI deduction looks more appealing).

For some solo advisor S corporations, the new QBI rules may also be a good excuse to shift away from an "improper" S corporation under a broker-dealer, since the now-infamous Flesicher case of 2017 ruled that brokers should not be shifting individually-paid commissions to an S corporation for FICA tax savings anyway.

From a Partnership or LLC into an S Corporation

This is one of the few potential entity structure changes you can pretty much write off for QBI deduction purposes.

A partner’s share of business profits is eligible for the QBI deduction in its entirety, whereas only the S corporation profits (and not salaries paid to owners) are eligible for the same treatment. Thus, for financial advisors and owners of other specified service businesses, there can be no increase in QBI deduction attributable to such a change, only a decrease (unless for some reason the partners receiving guaranteed payments from the partnership were willing to take less as an S corporation salary).

Notably, though, a change from partnership or LLC to S corporation could still be beneficial for other, non-QBI-deduction-related reasons. For example, a partnership making use of substantial guaranteed payments may benefit from a switch to an S corporation to reduce employment taxes, but 1) that is again unrelated to the QBI deduction (unless the salary is smaller than the guaranteed payments were), and 2) such a change may have been equally beneficial under the “old” law (where it was already appealing to use S corporations to reduce FICA taxes).

From an S corporation, or Partnership, to a C corporation

In limited circumstances, advisory firms may benefit from a change to a C corporation.

Although there is no QBI deduction available to owners of such entities, high-income owners of advisory firms may not see any such benefit anyway (due to their phaseout of the QBI deduction at high income levels).

On the other hand, despite the double-taxation associated with C corporations, the new 21% C corporation tax rate makes them far more appealing than in years past. For advisory firms experiencing rapid growth, where the limited tax deferral of a C corporation can be beneficial, or for those firms eyeing an IPO or similar liquidity event, the C corporation may deserve a second look.

A Final Note

While it’s never too early to get a jump start on figuring out how to maximize the QBI deduction, it’s probably best to avoid any major decisions, such as a change in entity structure, for the time being.

The reason is that while an exact release date is not known, there is widespread speculation that the initial proposed regulations for the QBI deduction will be made public soon - potentially in just the next few weeks, and possibly even before the end of this month.

These regulations will, no doubt, offer additional clarity, and could materially impact a number of important decisions. With initial guidance likely so close on the horizon, it may be best to plan now, but implement once the regulations are released and we have a greater sense of the IRS’s position on key matters.

So what do you think? Do you plan to restructure your business due to QBI deduction considerations? How are you advising clients who may have similar Specified Service Businesses? Do you think the IRS' initial guidance will change any QBI strategies? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!