Executive Summary

Following the long run-up in the US equity markets since the bottom of the 2008–2009 financial crisis, many investors with taxable investment accounts have likely found themselves with high embedded gains in their portfolios. While the gains signal portfolio growth, they also create challenges for ongoing management. Because when it comes time to rebalance the portfolio to its asset allocation targets – or to reallocate the portfolio to a new strategy – any trades made to implement those changes can generate capital gains, resulting in tax consequences for the investor.

Once a portfolio becomes 'locked up', i.e., unable to be managed without triggering capital gains, investors' options become limited. Charitably inclined investors can donate appreciated securities and avoid gains on the sale. If they don't plan to use the portfolio funds in their lifetime, they could simply hold the assets for heirs to preserve the stepped-up basis. Otherwise, the investor would traditionally have had to accept that taxes would impose a drag on their portfolio performance going forward.

One relatively new strategy, the Section 351 exchange, allows some investors to reallocate assets without triggering capital gains tax. Section 351 allows for tax deferral when assets are transferred to a corporation in exchange for that corporation's stock, provided the transferor owns at least 80% of the corporation following the exchange. Although the concept of Section 351 exchanges has existed for over a century, it has only recently been applied to individual investment portfolios.

The strategy works by pooling the portfolios of multiple investors in a newly created ETF, with the investors receiving ETF shares in return for the assets that they contributed. If the exchange meets the requirements of Section 351, it is tax-deferred for investors. And once inside the ETF 'wrapper', assets can be reallocated with no tax impact for the investors via the tax-efficient ETF structure, which makes use of in-kind creation and redemption of shares. In effect, investors can effectively trade a locked up for an ETF that can be managed with little or no tax impact at all!

However, to meet the requirements for tax-deferred treatment under Section 351, each investor's portfolio must meet a diversification test, where no single asset can exceed 25% of the portfolio's value and the top five holdings cannot exceed 50% of the overall value. Additionally, certain assets, like mutual funds, alternative assets, and REITs, may not be eligible for exchange, although other ETFs generally are.

For financial advisors, Section 351 exchanges present a potential solution for clients with high embedded gains, such as those who through the use of tax-loss harvesting have lowered their portfolios' basis to the point where it's no longer possible to harvest any losses to offset the gains realized in reallocating the portfolio. Recently, several ETF sponsors have launched ETFs seeded in-kind by individual investors, creating a new channel for advisors who want to take advantage of Section 351 exchanges for clients. Some providers even offer services to help advisors launch their own ETFs seeded by their clients' funds.

While the options for Section 351 exchanges remain limited – and some advisors may not yet be comfortable recommending them due to their short track record – the strategy is still worth watching. If it gains traction, it could be a helpful tool for advisors to implement more tax-efficient investment strategies – while overcoming the inconvenient tax friction of implementing the strategy to begin with!

If an investor has stayed in the equity markets over the last 15 years, there's a good chance they have substantial unrealized capital gains in their portfolio. During that time, the S&P 500 has risen over 600%, while more diversified 60/40 portfolios have grown by over 300%. This means that someone who bought and held onto their investments in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis could now easily have holdings worth three to six times what they originally paid for them.

While it's obviously a good sign to have embedded gains in a portfolio – since it means the investments have performed well – the downside for assets held in a taxable account is that high unrealized gains can make the account difficult to manage without incurring taxable income. Rebalancing a portfolio to its target asset allocation often requires selling over-allocated (i.e., more appreciated) assets in order to buy under-allocated (less appreciated) assets, triggering taxable gains whenever trades are made to keep the portfolio aligned with the investor's risk/return goals. And if the investor needs to shift the portfolio to an entirely new asset allocation, it can be difficult to do so without generating significant taxable income when the old appreciated assets are sold to make way for the new allocation.

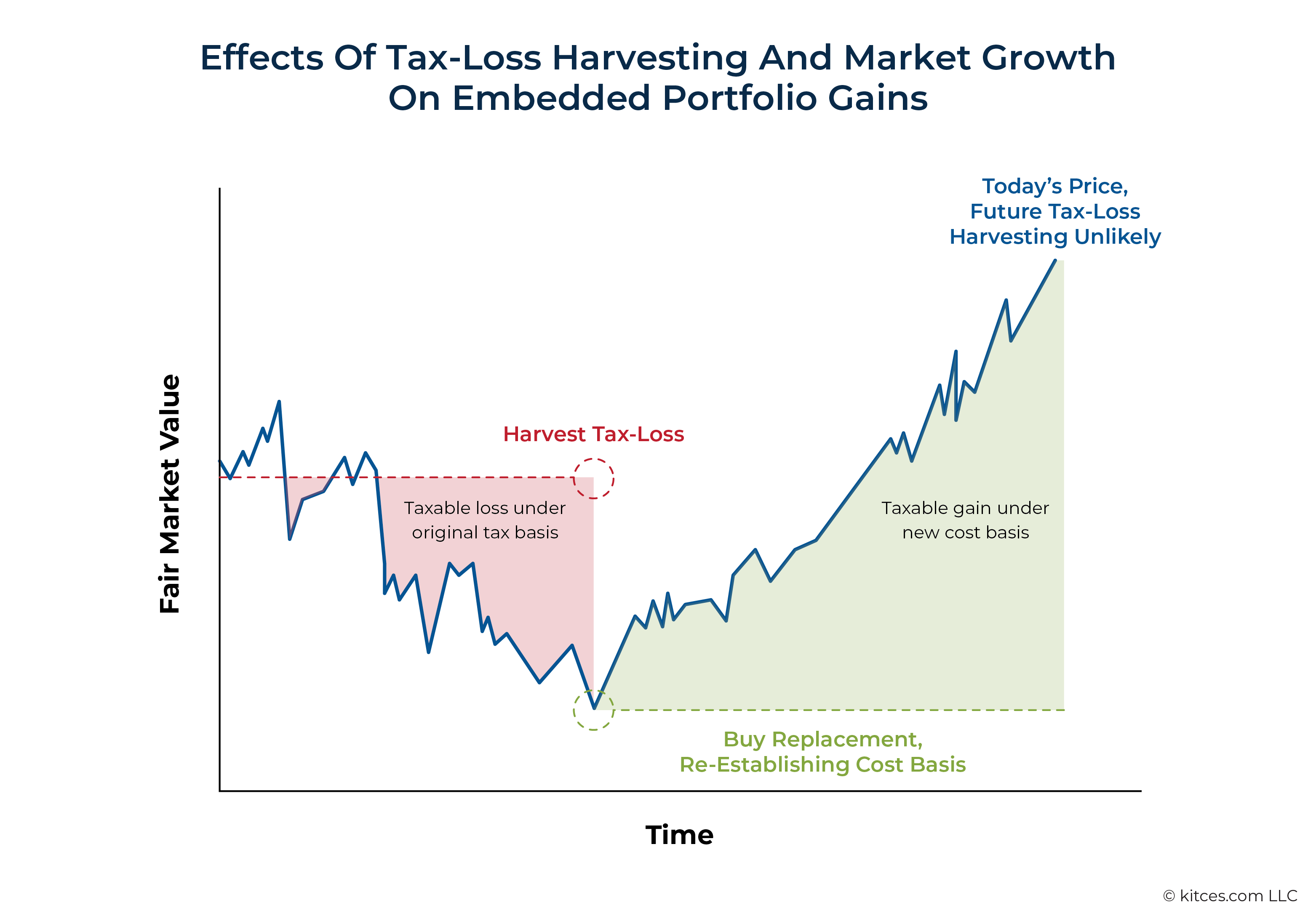

Advisors often offset the tax impact of trading through tax-loss harvesting, i.e., selling assets at a loss to counterbalance gains and minimize the investor's tax burden over time. In recent years, direct indexing technology has supercharged tax-loss-harvesting strategies by allowing investors to hold individual securities that track an index like the S&P 500. This makes it possible to take advantage of frequent short-term price movements to continually harvest losses throughout the year. The investor can then buy a similar (though not identical) security to avoid a wash sale that defers the loss, or simply wait out the 30-day wash sale period before repurchasing the original security.

But there's a tradeoff: Each time a security is sold at a loss and replaced with another, it lowers the cost basis of the portfolio. And although individual holdings may fluctuate on a day-to-day basis, markets tend to move upward over time. As a result, the account's basis moves downward while the overall portfolio value moves upward, making it harder to find capital losses to harvest. Eventually, there's little ability to make any moves in the portfolio without incurring taxable gains, and the portfolio has become "locked up".

Once a portfolio becomes locked up, the options for avoiding additional tax on trading are limited. If the owner doesn't plan to use the funds in the portfolio during their lifetime, they can avoid capital gain taxes entirely by contributing the portfolio to a charitable organization, either directly or via a charitable remainder trust or donor-advised fund. Or they can simply hold the assets as is, without any further trading, until death to pass to their heirs with a stepped-up basis.

But if the portfolio's owner does plan to use the funds during their lifetime, it becomes harder to avoid the tax consequences of rebalancing once the portfolio becomes locked up. This can result in a drag on the portfolio's pre-tax performance if funds have to be withdrawn to pay for the tax burden – and has led some investors and advisors to look for new solutions to minimize the tax impact of trading and rebalancing in taxable portfolios.

How Section 351 Exchanges Work

The problem of what to do with portfolio assets that are 'locked up' due to high embedded gains has sparked interest in a relatively modern twist on an existing tax strategy: the Section 351 exchange.

IRC Section 351(a) states:

No gain or loss shall be recognized if property is transferred to a corporation by one or more persons solely in exchange for stock in such corporation and immediately after the exchange such person or persons are in control (as defined in Section 368(c)) of the corporation.

In practice, what that means is that appreciated property transferred to a corporation in exchange for its stock can qualify for tax-deferred treatment of any gain or loss on the property, provided the transferor owns at least 80% of the corporation immediately afterward.

Section 351 has existed since 1954 (with similar provisions dating back to 1921) to encourage business formation by preventing property contributions to start a business from triggering taxable events.

For example, Company X decides to form a subsidiary, Company Y, to manufacture widgets. Company X transfers a factory worth $2 million (with a cost basis of $1 million) to Company Y in exchange for 100% of Company Y's stock.

If this were a taxable transaction, Company X would owe capital gains tax on the $1 million gain on the factory, even though it hasn't liquidated or given up control of the property through its ownership of Company Y. However, under Section 351, the transfer is tax deferred and there is no tax due on the transaction. Company X's tax basis in the factory simply carries over to its new shares in Company Y.

The modern twist on this strategy is that instead of transferring physical assets (e.g., factories) to a newly formed corporation, one or more individuals or businesses can instead transfer financial assets (e.g., stocks or bonds) into a newly formed Exchange-Traded Fund (ETF) structured as a corporation.

In exchange, the investors receive ETF shares (at the tax lot level) without recognizing taxable income, as long as they collectively own at least 80% of the new ETF's shares immediately after the exchange.

The '25/50 Diversification Test' For Section 351 Exchanges Into An Investment Company

At least in theory, Section 351 lays the groundwork for investors to convert a portfolio of individually owned assets into a more tax-friendly corporate structure without recognizing any capital gains on the trade.

The caveat, though, is that Section 351(e) explicitly prohibits tax-deferred treatment from applying to any transfers of property to an "investment company". Treasury Regulations 1.351-1(c) clarifies that an "investment company" consists of any one of the following:

- A Regulated Investment Company (RIC);

- A Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT); or

- Any corporation where at least 80% of its assets (excluding cash and debt receivable) consist of readily marketable stocks or securities, RICs, or REITs.

Since ETFs are a type of RIC, they generally fall under the Section 351(e) restriction, meaning tax-free transfers to ETFs are not allowed.

However, the IRS regulations add that the Section 351(e) restriction only applies when two conditions are met:

- The transferee is an investment company; and

- The transfer results in the "diversification" of the transferor's interests.

Treasury Regulations 1.351-1(c)(6) further specify that if a transferor's assets are already diversified prior to the exchange, the transfer does not count as diversification. This means that ETFs (or any other type of investment company) can be used in a Section 351 exchange, as long as the assets transferred in the exchange are already diversified.

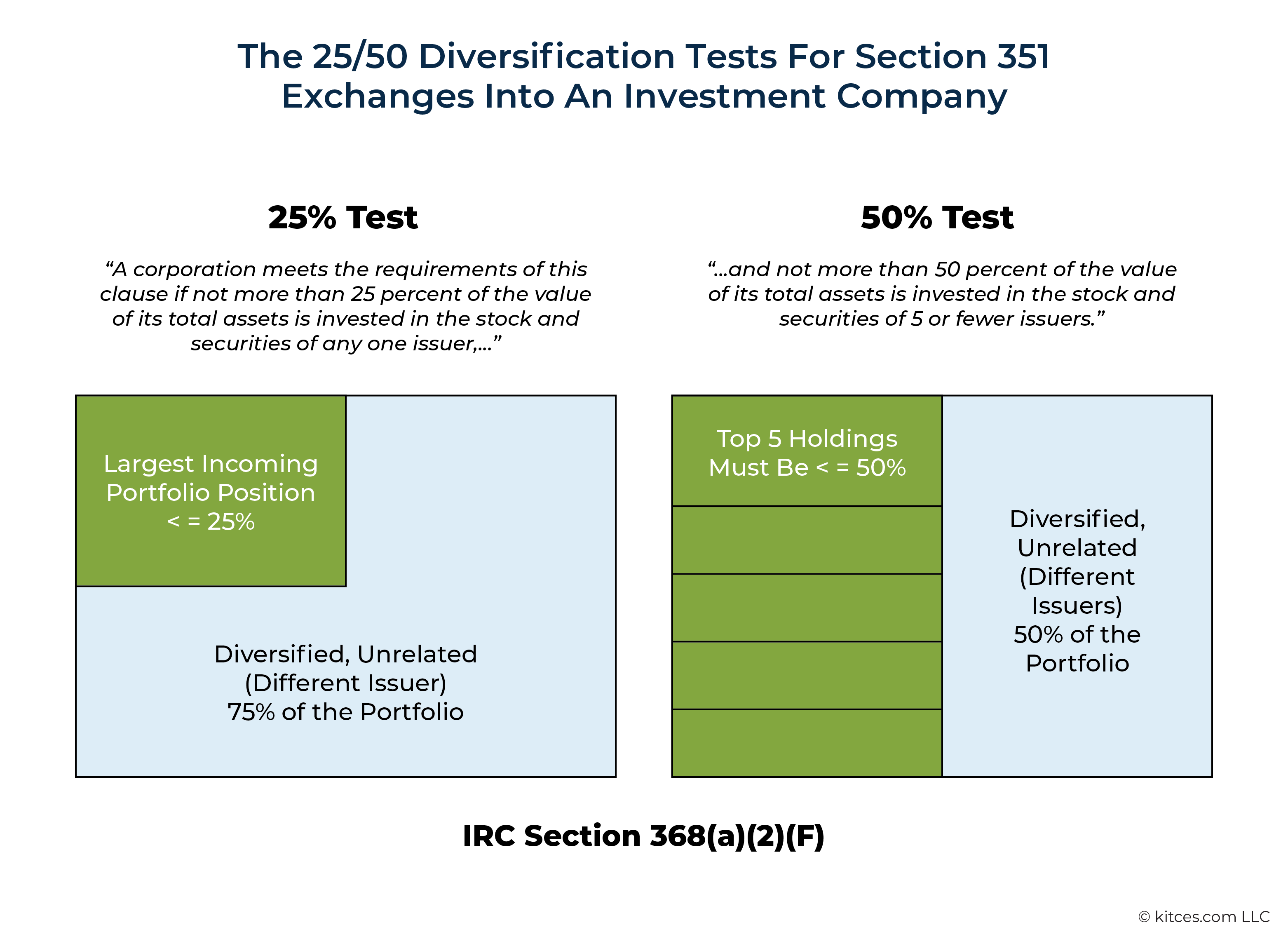

To determine whether a portfolio is considered diversified, the IRS applies the Section 368(a)(2)(F) 25/50 test, which states that the portfolio is considered diversified if:

- No more than 25% of the portfolio's assets are made up of the stock or securities of a single company; and

- No more than 50% of the portfolio's assets are made up of the stock or securities of any five or fewer companies.

Significantly, Section 368(a)(2)(F)(ii) specifies that, for purposes of the 25/50 diversification tests, shares of a Regulated Investment Company that are transferred into the new company are treated as if they were a "proportionate share of the of the assets held by such company or trust".

In other words, if a fund such as an ETF is transferred into another ETF via a Section 351 exchange, the IRS will view the transferred ETF on a 'look-through' basis, and examine its underlying assets to determine whether it meets the diversification requirements for tax-deferred treatment under IRC Section 351. So, for example, shares of an S&P 500 index ETF would be treated not as a single asset but as an agglomeration of each of its 500 individual portfolio companies. This makes it much easier for ETF-based portfolios to pass the 25/50 diversification tests for a Section 351 exchange, since a portfolio consisting of 'only' one or two ETFs can still meet the requirements as long as the ETFs are themselves diversified.

To sum it up, then, to make a Section 351 exchange into an investment company like an ETF, the transaction must meet both the general requirements of Section 351(a) and the requirements of Section 351(e) and the related Treasury regulations that apply specifically to transfers to investment companies. This means that the exchange needs to have three broad characteristics:

- Each investor contributes an already-diversified portfolio that passes the 25/50 diversification test (i.e., no single holding exceeds 25% of the portfolio's value, and the top five holdings don't exceed 50%, with regulated investment companies like ETFs treated on a look-through basis);

- The transferor(s) receive stock in the new company (e.g., ETF shares) in exchange for the transfer; and

- The transferor(s) retain at least 80% ownership of the transferee immediately following the exchange.

Nerd Note:

If multiple investors contribute assets to an investment company via a Section 351 exchange and one or more fail the 25/50 diversification test, the exchange remains tax-free for those who passed the test. Only the investor(s) whose assets failed the diversification test will have their transfer treated as a taxable event.

Seeding ETFs Via Section 351 Exchange

While a Section 351 exchange can theoretically be used to transfer assets into any investment vehicle structured as a corporation, it is most commonly applied to Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs). This is because ETFs have an inherently tax-friendly structure that is conducive to investing in a taxable account.

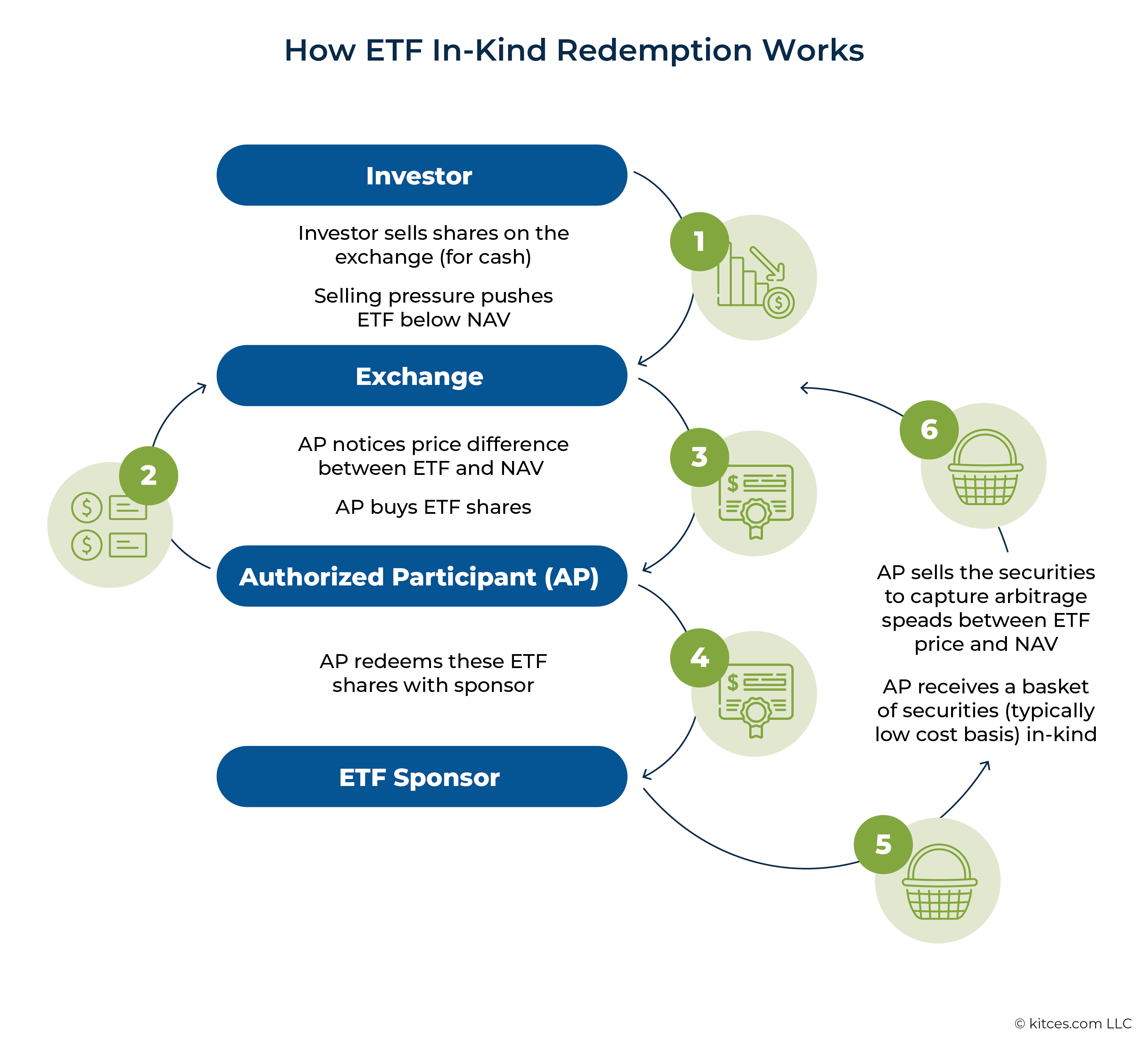

Unlike mutual funds, which must buy and sell their holdings for cash (potentially resulting in capital gains or losses that are passed on to shareholders as taxable income each year), ETFs deliver and receive assets in-kind from third party financial institutions called Authorized Participants (APs) – typically institutional broker-dealers. These APs facilitate the delivery and receipt of securities in exchange for shares of the ETF, a process that qualifies for tax-free treatment under IRC Section 852(b)(6). As a result, these redemptions are nontaxable to the ETF and, by extension, its shareholders.

As shown below, APs play an important role in balancing ETF supply and demand by capturing arbitrage opportunities:

- When the ETF's share price rises above its Net Asset Value (NAV), APs contribute securities to the ETF in exchange for newly created ETF shares.

- When the ETF's share price declines below its NAV, APs redeem ETF shares in exchange for securities.

This continuous arbitrage process relies on movements in the fund that offer opportunities to reallocate the ETF's holdings, without recognizing taxable gains, toward the investment objectives stated in the ETF's prospectus.

As a result, ETFs generally don't incur taxable gains for their investors when funding share redemptions in-kind. Similarly, they can also use in-kind redemptions for ongoing portfolio rebalancing with minimal tax consequences. Other than dividend distributions from the fund's underlying portfolio companies or instances where ETFs sell holdings for cash to cover costs, ETFs typically produce very little ongoing taxable income for investors. This makes them especially useful for taxable brokerage accounts, where lower taxable income reduces the drag of taxes on the portfolio's performance.

And so, when using a Section 351 exchange to transfer assets tax-deferred into a new investment vehicle, it makes sense to use an ETF as the vehicle: Not only can the assets be moved into the ETF 'wrapper' via the Section 351 exchange to defer the realization of any gains, but once inside the ETF, they can be reallocated to the ETF's target investment mix without incurring taxable income through the ETF's in-kind share creation and redemption process.

How ETF Seeding Works

The key limitation to transferring assets tax-deferred into an ETF is that, under Section 351(a), individual(s) transferring assets need to own at least 80% of the transferee corporation to defer taxes on the exchange. As a result, Section 351 transfers can only be used to contribute assets to a newly created ETF, not an existing one where it wouldn't be realistically possible to meet the post-transfer ownership requirements.

Here it's helpful to give a brief overview of the mechanics of how ETFs come into existence. ETFs are formed by a process called "seeding", where the fund's initial investors provide the capital used to buy the ETF's initial underlying holdings. Traditionally, ETF seeding is done by banks or financial institutions, which contribute cash or securities that become the ETF's initial holdings in return for shares of the ETF.

Historically, the ETF seeding process has usually been carried out by financial institutions that seek to sell their ETF shares as soon as they can trade them, rather than by investors who plan to keep their shares long-term. But there's no rule preventing individual investors from seeding an ETF – it's just easier for a single large institution to raise the capital needed to launch the ETF than it is for hundreds or thousands of individual investors to coordinate their own contributions.

Still, some advisory firms have successfully launched their own ETFs seeded by client assets. In response, white-label ETF firms like ETF Architect, Tidal, and ETC have emerged to help facilitate the ETF creation process. But launching a proprietary ETF comes with its own set of financial and operational hurdles: ETFs, in general, are expensive to launch and run, with the startup costs of a new ETF running from $40,000–$150,000 and the ongoing annual cost of running the fund reaching $200,000 or more.

In order to simply break even while charging a reasonable expense ratio (say, 0.5%), an advisor would need to seed the ETF with a minimum of $200,000 ÷ 0.5% = $40,000,000 of client assets (and even more if they plan to charge a lower expense ratio).

The First Wave Of Publicly Seeded ETFs

Recently, several retail ETF issuers have announced plans to launch ETFs seeded in-kind by individual investors via Section 351 exchange. Three funds have already been launched: Stance's Sustainable Beta ETF (November 11, 2024), Cambria's Tax Aware ETF (December 18, 2024), and Longview's Advantage ETF (February 25, 2025). Cambria is also in the process of launching a second fund, Cambria Endowment Style ETF, expected to launch on April 9, 2025.

The rapid succession of these ETFs seeded in-kind via Section 351 exchange is notable for advisors; for the first time, it suggests that a Section 351 exchange into an ETF could be a viable strategy for clients without requiring the advisor to create their own ETFs (and take on the associated costs and operational challenges). If publicly seeded ETF launches become more common in the future, advisors could help their clients choose from an array of ETFs open to seeding, then work with the chosen ETF sponsor to facilitate the paperwork and asset movements needed to complete the exchange. Which, at least in theory, could make it much easier to move a client's 'locked-up' portfolio into a more tax-efficient vehicle – without the significant up-front tax cost of selling the entire portfolio.

However, with only a handful of ETFs having been seeded in-kind so far, that future is still a long way off. Still, the recent wave of in-kind seeded ETFs has sparked some important questions on how seeding an ETF via a Section 351 exchange would work in practice and whether the potential tax benefits of doing so would even make it a worthwhile strategy.

The Tax Benefits Of Section 351 Exchanges

At a base level, the value of a Section 351 exchange lies in its ability to defer the tax impact of shifting from one investment strategy to another. An investor who would have otherwise needed to carry out a complex multi-year liquidation strategy to minimize the tax hit from reallocating their portfolio can, theoretically, use a Section 351 exchange to reduce the tax 'friction' of the reallocation to zero.

Although the tax on any embedded gains is only deferred, not eliminated – the tax will still be owed if and when the ETF is sold, unless it's either donated to a charity (potentially avoiding capital gains taxes altogether) or held until death to receive a step-up in basis. Still, deferring capital gains taxes allows for the continued growth of the dollars that would have otherwise gone toward paying capital gains tax when the portfolio was reallocated.

So for a given investor, the value of a Section 351 exchange comes down to two key factors: 1) How much the portfolio would benefit from shifting to a different strategy, and 2) How big the tax impact would be if the investor didn't use a Section 351 exchange to reallocate their portfolio.

When A Portfolio Can Be Reallocated With A Section 351 Exchange

From a portfolio perspective, there are many reasons why an investor might want to shift investment strategies – whether it's to better match the risk/return profile of the current portfolio with the investor's own needs, reduce high fees that drag on the portfolio's performance, or minimize taxable income through dividends or capital gains distributions that likewise bring down the portfolio's after-tax return.

Transferring portfolio assets into an ETF with a Section 351 exchange can potentially solve some of these problems, but not all of them.

Because the Section 351 rules require assets transferred into an investment company to already be diversified, Section 351 exchanges can't be used to diversify a portfolio with highly concentrated holdings. This is a key distinction from exchange funds, a different type of investment vehicle governed by IRC Section 721 that's commonly used by investors with concentrated stock holdings (e.g., startup employees with employer stock compensation) to pool together their holdings with other investors with their own concentrated holdings in order to create a more diversified total portfolio. While media coverage, and in some cases ETF sponsors themselves, have compared seeding an ETF via Section 351 exchange to an exchange fund, the two are not the same. Section 351 exchanges require that the seeding investors' portfolios are already diversified before they're transferred to the ETF, which means they can't be used to diversify out of a concentrated position.

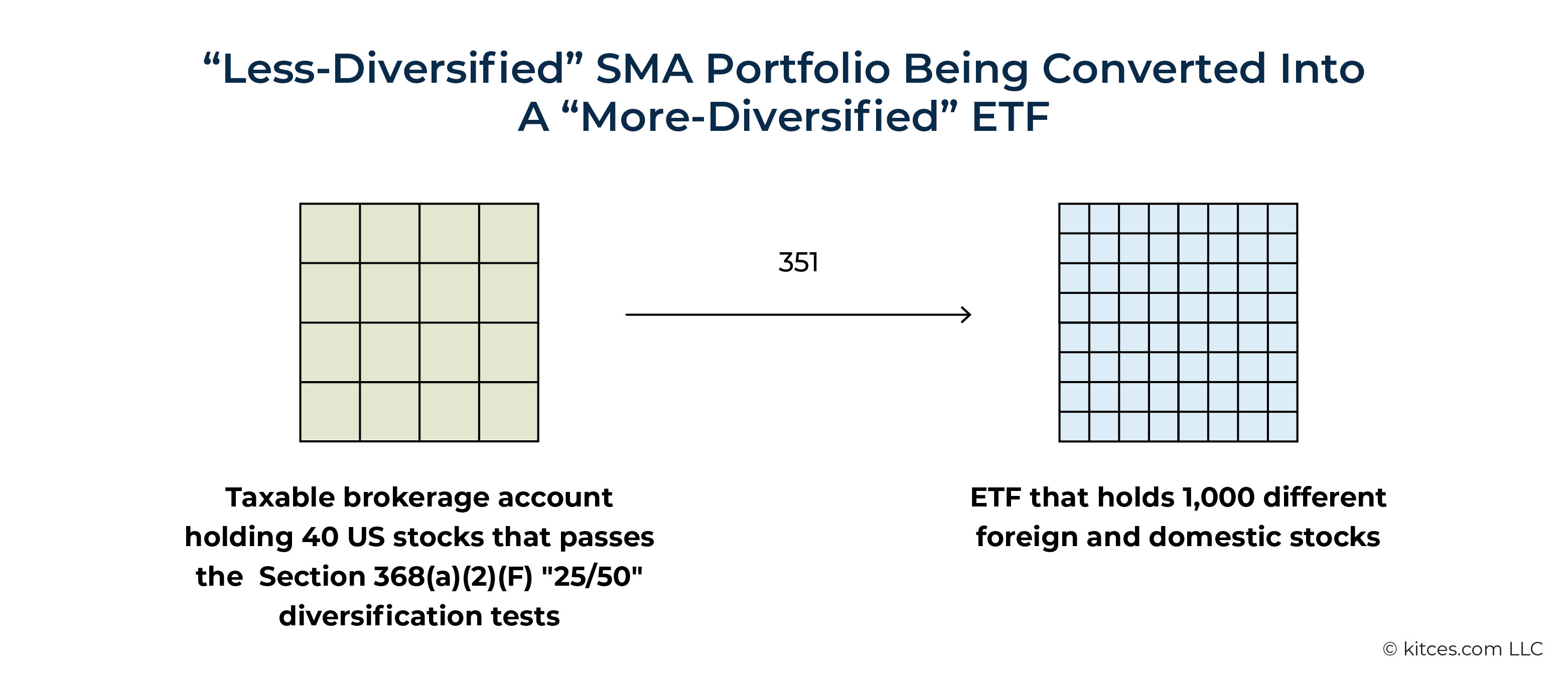

At the same time, however, Section 351 exchanges can still be used to increase the diversification of a relatively undiversified portfolio as long as it meets the 25/50 diversification test of Section 368(a)(2)(F).

For example, a portfolio of 15 technology stocks might not be well-diversified from an investment risk standpoint. However, if no single stock makes up more than 25% of the portfolio and the top five holdings don't exceed 50% of the portfolio, the portfolio could still be "diversified" enough to qualify for a Section 351 exchange. From there, the ETF can reallocate using in-kind exchanges to significantly increase the diversification of the original portfolio by adding additional companies and/or expanding into other sectors or industries – even though the original portfolio was already diversified according to the rules of Section 351.

While IRC Section 351 doesn't explicitly restrict the types of assets that can be transferred, the mechanics of ETF in-kind redemptions limit what ETFs will actually accept. In practice, ETFs generally won't accept mutual fund shares, alternative assets like private equity or hedge fund positions, commodities, or cryptocurrency assets. So, if the reason for changing portfolio strategies is to exit any of those investment vehicles or asset classes, it won't work to do so via a Section 351 exchange into an ETF.

For instance, if an investor has a portfolio of high-fee mutual funds with large capital gains distributions that they want to convert into more tax-efficient ETFs, they would not be able to use a Section 351 exchange to transfer those shares into an ETF. Instead, they would first need to sell the mutual funds, recognize any embedded capital gains, and then reinvest the proceeds into an ETF. (ETFs do accept shares of other ETFs, as noted earlier, so it's possible to take a current portfolio of ETFs and convert it into a single new ETF via Section 351 exchange.)

Nerd Note:

SEC rules require that an incoming portfolio must be aligned with the ETF's prospectus. For example, if an ETF's prospectus states that it only invests in non-US stocks, then it wouldn't be able to receive a portfolio of US stocks as a seeding contribution. In practice, though, publicly seeded ETFs tend to have relatively broad investment mandates that give the funds leeway in what types of assets they can receive. The ETF sponsor may still reject any contributions that create conflicts with the fund's stated investment strategy.

Additionally, ETF sponsors might not allow an incoming portfolio to have exactly 25% of a single position – they may cap the amount at 20% in order to ensure that market movements don't inadvertently cause a violation of the diversification rules.

And so at the bottom line, two types of portfolios are a strong fit for conversion into an ETF via a Section 351 exchange.

The first is a portfolio of individual stocks that needs to be "de-risked" in some way, because it's too concentrated in a small number of companies, individual countries, sectors, or asset classes, with the caveat that the portfolio needs to meet the 25/50 diversification rules described earlier to receive tax-deferred treatment in the Section 351 exchange. For these portfolios, the Section 351 exchange into an ETF could allow for more diversification while continuing to defer taxes on any unrecognized gains.

The second is a portfolio experiencing a significant drag on its returns from a combination of high management fees and/or taxable income generated by the portfolio. The caveat here is that many of the portfolios with this issue are made up of mutual funds, which are generally ineligible for seeding an ETF.

Nerd Note:

Although individual mutual fund shares generally can't be used to seed an ETF via a Section 351 exchange, an entire mutual fund can convert into an ETF by transferring its holdings into a newly created ETF, as Dimensional Fund Advisors did when it converted several of its long-standing mutual funds into ETFs in 2021.

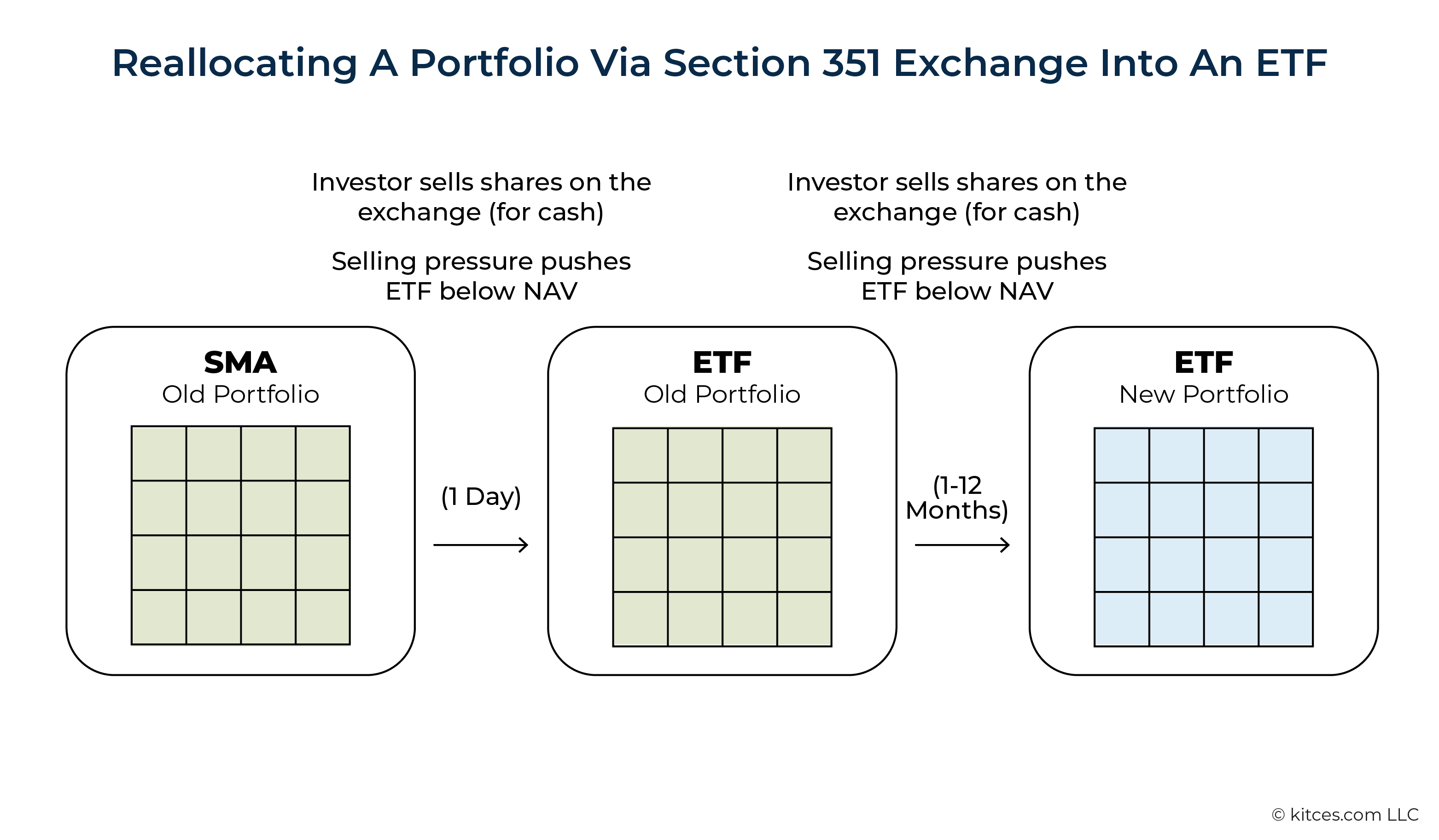

Notably, some Separately Managed Account (SMA) and Direct Indexing (DI) portfolios might also experience high return drag, particularly if the portfolio has high embedded gains and there are few opportunities to harvest losses, resulting in taxable gains any time the portfolio is rebalanced.

In these cases, transferring the portfolio into an ETF via Section 351 exchange could help minimize the tax drag of ongoing portfolio rebalancing once there are no more opportunities for tax-loss harvesting. Additionally, if the ETF's expense ratio is lower than the management fee of the SMA or DI platform, there might also be an opportunity to reduce fees with the ETF.

The Tax Deferral Impact Of A Section 351 Exchange

One of the biggest challenges of reallocating an investment portfolio – whether to adjust risk and return or to reduce fees or tax drag – is the tax impact of selling the existing holdings. When there are large embedded gains in the old portfolio, selling everything at once can generate a significant tax bill (especially if doing so bumps the investor from the 15% up to the 20% or 23.8% capital gains tax brackets). Which in turn takes money out of the portfolio that would otherwise be able to grow and compound over time.

A Section 351 exchange, like other tax deferral strategies, helps eliminate this tax friction by allowing the assets to be transferred without an immediate tax event. This makes it similar to Section 1031 exchanges of real estate assets, Section 1035 exchanges of life insurance or annuity policies, and Section 721 exchange funds for concentrated positions mentioned earlier, as a class of transaction that allows for the deferral of gains provided that certain conditions are met.

The benefits of deferring taxes on an exchange are greatest when the tax consequences of the exchange would have had the biggest impact. The magnitude of the impact is a function of two factors: 1) The amount of taxable income that would be realized by making the change, and 2) the tax rate of the portfolio's owner. The more capital gains income that would be realized from selling the current portfolio and the higher the tax rate that the portfolio's owner pays on that income, the bigger the tax impact from making the change – and the greater the potential benefit from tax deferral.

Evaluating When It Makes Sense To Use A Section 351 Exchange

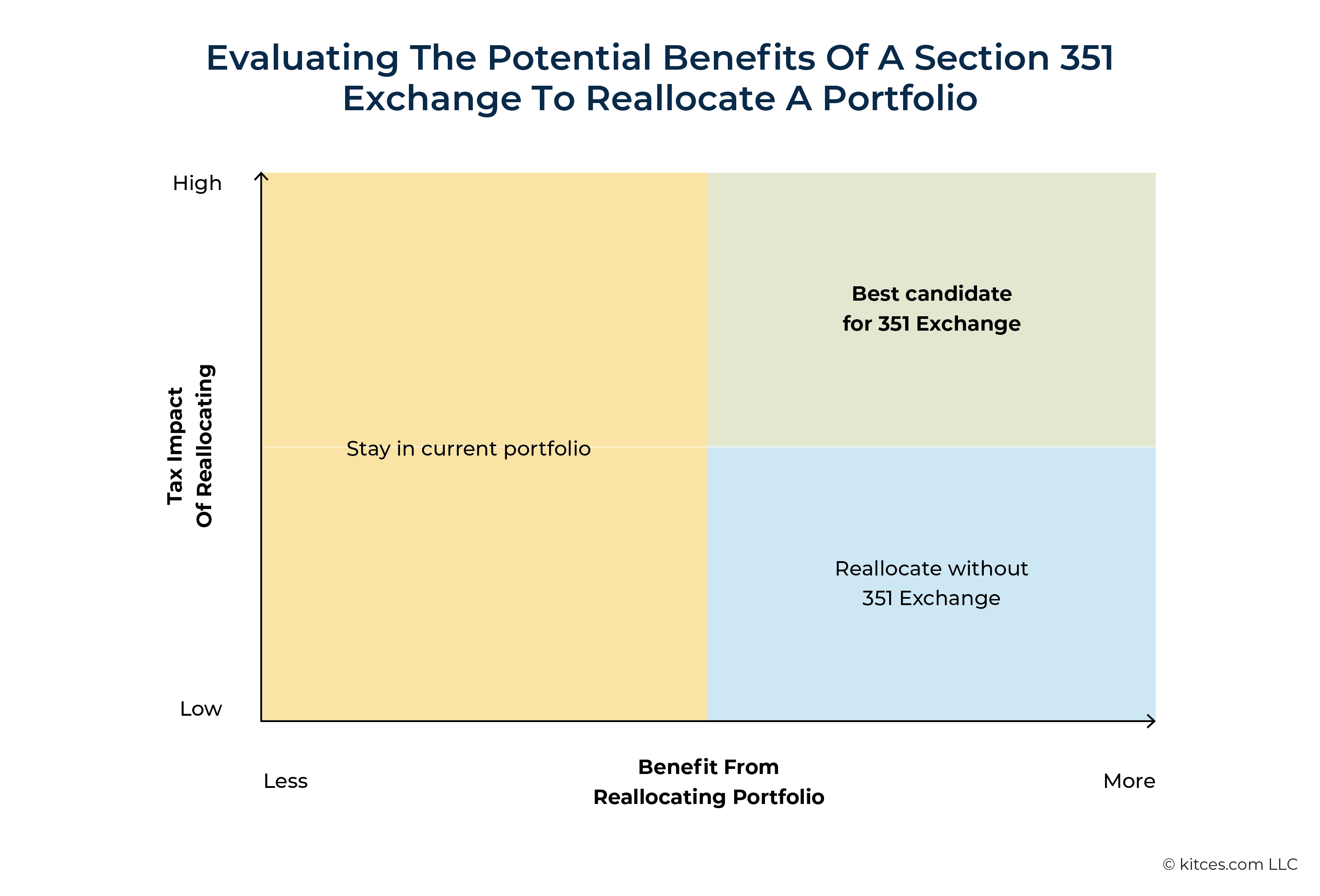

Ultimately, the potential benefits of seeding an ETF via a Section 351 exchange move along two dimensions: 1) Whether reallocating the current portfolio into an ETF makes sense, and 2) whether doing so would have a significant tax impact.

If there's no urgent need to reallocate the portfolio, there's little reason to use the Section 351 exchange. If the portfolio is already adequately diversified, appropriate for the client's risk and return needs, tax-efficient, and has reasonable fees, it won't necessarily be improved any further by converting it into an ETF.

Likewise, if the portfolio would benefit from being reallocated, but there would be little or no tax impact from simply selling the current portfolio and buying the ETF, then a Section 351 exchange wouldn't provide much value, since there would be no tax to defer to begin with.

For example, if there are enough unrealized losses in the portfolio that can be harvested to offset the capital gains from selling, then the portfolio could be reallocated without any tax impact without using a Section 351 exchange. And if the investor is in the 0% capital gains tax bracket, it could be better not to use a Section 351 exchange, since realizing gains in the 0% capital gains bracket resets the investor's cost basis at a higher level without incurring any additional (Federal) income tax.

But if there's a good reason to shift the portfolio into a different strategy, and the potential for a high tax impact from selling, then using a Section 351 exchange to transfer the portfolio into an ETF could be worth considering – assuming the portfolio meets the diversification requirements needed to receive tax-deferred treatment, and that it's comprised of assets that ETF sponsors will accept for the exchange.

Risks And Downsides Of Section 351 Exchanges

Failure To Receive Tax-Deferred Treatment

As noted earlier, there are specific rules about the assets that can be transferred into an ETF while receiving tax-deferred treatment in a Section 351 exchange. For the exchange to be tax-free, the portfolio needs to meet the 25/50 diversification test prior to the exchange, and it must consist of eligible assets – typically stocks, bonds, and/or ETFs (mutual funds and most alternative asset classes are not accepted for seeding new ETFs).

It's possible that a Section 351 exchange could fail if the incoming portfolio fails to meet the 25/50 diversification requirements prior to the exchange, or the 80% ownership requirement immediately following the exchange. This could occur if the investor or ETF sponsor fails to properly analyze the portfolio's holdings, or if sudden market movements unexpectedly shift asset values over the required thresholds. In either case, if the IRS deems the transfer to be a taxable transaction, the investor would recognize any embedded capital gains – which could also result in the ETF sponsor incorrectly reporting the holding period and cost basis of that investor's shares in the fund.

There's an additional risk that the Section 351 exchange may be misreported by the investor's custodian. If the custodian incorrectly classifies the Section 351 as a taxable sale instead of a tax-free exchange, they may issue a Form 1099 to the investor (and the IRS). While not necessarily negating the Section 351 exchange for the investor (assuming it's performed correctly), this may trigger an audit from the IRS when the custodian's records mismatch what is reported by the investor.

High Fees And Tracking Error

Outside of the risk of the Section 351 exchange failing to qualify for tax-deferred treatment, the biggest obstacle to using this strategy to seed ETFs is simply the limited number of available options for doing so at the moment. The few publicly seeded ETFs launched so far have come from comparatively smaller ETF sponsors with active investment strategies, which is concerning from a due diligence perspective as the ETFs (or any predecessor mutual funds) have little or no track record by which to evaluate the fund's manager or investment strategy.

Additionally, publicly seeded ETFs tend to have a higher ongoing expense ratio than traditional index-tracking ETFs. This is because the ETF sponsor pays not only the cost of setting up and running the ETF but also (in the case of publicly seeded ETFs) the cost of legal counsel, an opinion letter, and operations support to ensure that the in-kind seeding of the funds is done properly according to Section 351.

For example, the average index-tracking equity ETF has around a 0.15% expense ratio, while the Stance Sustainable Beta ETF and Cambria Tax Aware ETF both have a 0.49% expense ratio.

If the practice of offering publicly seeded ETFs proves successful for the first few sponsors, it's possible that some of the larger ETF sponsors like Vanguard and BlackRock will follow suit. This could have the dual effect of giving more potential options for investors to choose from (since now they are mostly confined to waiting until the 'right' strategy for them becomes available as a new publicly seeded ETF) as well as driving down the cost with the bigger sponsors' size and scale.

But for now, other than for advisory firms that are willing to shoulder the cost of launching and managing their own ETFs to be seeded by their existing clients, it would take a lot of luck to deal with the conundrum of what to do with a client's "locked-up" portfolio at the exact time that an ETF that's just right for that client happens to be receiving in-kind seeding transfers.

Finally, it's worth noting that ETFs seeded in-kind via Section 351 exchanges can take time to actually reallocate their initial 'seed' holdings (which can comprise holdings contributed by many different investors) to their final target allocations. For example, as of February 12, 2025, nearly two months after its launch, Cambria's Tax Aware ETF still comprised many of the funds contributed during its seeding process, with Vanguard's Total Stock Market ETF making up over 12% of its portfolio, and Nvidia accounting for more than 5%.

The cost to investors is that it could take up to 12 months for the ETF to fully align with its intended investment strategy. It takes time to completely reallocate an ETF in a way that doesn't disproportionately affect the values of its underlying holdings (or create scrutiny from the IRS that the Section 351 exchange lacked economic substance other than to avoid taxes, which could nullify the tax-deferred treatment of the exchange). In other words, while a Section 351 exchange into an ETF can be tax-efficient, it isn't necessarily instantaneous. Investors should be aware of potential short-term tracking error as the ETF fully implements its intended investment strategy.

Evaluating Section 351 Exchanges Compared To Other Strategies

There are some interesting potential tax benefits to seeding an ETF via a Section 351 exchange. Given the emergence of and attention surrounding the first generation of publicly seeded ETFs, advisors may soon find clients asking whether this strategy would make sense for them.

In these scenarios, it's important to evaluate a Section 351 exchange not in a vacuum but in comparison to other available options – including both doing nothing (i.e., sticking with their current portfolio as is) and reallocating to a new portfolio without using a Section 351 exchange.

As discussed earlier, the impact of a Section 351 exchange will vary depending on the investor's individual situation. For some, it might really be worth pursuing, while for others, there may be better options available.

Scenario 1: 'Rescuing' A Portfolio With High Embedded Gains

The most obvious use case where a Section 351 exchange might be worth considering is when an investor has a 'locked-up' portfolio – such as a Separately Managed Account (SMA) or direct indexing account – with high embedded gains and no losses available for tax harvesting.

Example 1: Libby is a 45-year-old attorney. 15 years ago, she inherited a taxable brokerage account from her grandmother worth $300,000. Her financial advisor managed the account as an SMA and was very efficient in harvesting losses to offset gains in the portfolio. Today, the portfolio is worth $1 million, but as a result of all the tax-loss harvesting its cost basis is only $200,000.

At this point, there are few opportunities left to harvest losses, and Libby, who is in the top capital gains tax bracket of 23.8%, faces significant taxable income from both capital gains from rebalancing and dividends from the underlying holdings.

Libby's SMA portfolio has earned an average return of 8% per year, with 6% coming from price appreciation and 2% from dividends. The portfolio has a 10% annual turnover rate (meaning that 10% of the holdings are sold each year for rebalancing or reallocation) and has a 0.25% annual management fee.

Libby's advisor projects that, after 20 years, the portfolio will be worth $3,385,837 (after accounting for management fees and taxes on portfolio income). At that point, though, the portfolio's cost basis will have risen to $2,408,683, leaving unrealized gains of $3,385,837 − $2,408,683 = $977,154. And after accounting for the embedded capital gains, the after-tax portfolio value would be $3,385,837 – (23.8% × $977,154) = $3,153,274, equating to a 7.0% after-tax, after-fee return.

Libby's advisor decides to explore how to reallocate the SMA portfolio to a more tax-efficient investment strategy.

Option 1: Move The SMA Into A Portfolio Of ETFs

The first option Libby's advisor considers is a portfolio of ETFs that roughly matches the 8% annual gross return of the SMA (including the 2% dividend yield). The portfolio won't generate taxable income from turnover (since the ETFs can rebalance in-kind) and has a lower average expense ratio of just 0.15%.

However, to move into the new portfolio, Libby would need to liquidate her existing SMA, triggering $1,000,000 − $200,000 = $800,000 in capital gains. With a 23.8% tax rate, this would result in a 23.8% × $800,000 = $190,400 tax bill, leaving her with only $1,000,000 – $190,400 = $809,600 to invest into the new portfolio.

After 20 years, the new portfolio would be worth $3,407,726 on a pre-tax basis, with a cost basis of $1,527,930, leaving unrealized gains of $1,879,796. After taxes on those embedded gains, her portfolio's after-tax value would be $3,407,726 – (23.8% × $1,879,796) = $2,960,335, equating to a 6.7% after-tax, after-fee return.

In other words, reallocating into the new "tax-efficient" portfolio resulted in a worse outcome, after accounting for the tax paid to reallocate into the portfolio in the first place!

Option 2: Use A Section 351 Exchange To Transfer Into A New ETF

Instead of reallocating into a portfolio of existing ETFs, Libby's advisor considers a new ETF that could be seeded with in-kind transfers via Section 351 exchange. Again, the portfolio's expected return before taxes and fees is 8%, which includes a 2% dividend yield, but the management fee of the publicly seeded ETF is 0.5%, higher than Libby's original portfolio management fee of 0.25%.

By using a Section 351 exchange to transfer her assets into the new ETF, Libby won't pay any capital gains tax when reallocating her portfolio – the gains would stay deferred until she needs to sell the ETF.

After 20 years, Libby's advisor projects the portfolio would be worth $3,997,030 on a pre-tax basis, with a cost basis of $1,060,667, resulting in unrealized gains of $2,936,363. After accounting for the embedded gains, her portfolio's after-tax value is $3,997,030 – (23.8% × $2,936,363) = $3,298,176, equating to an after-tax after-fee return of 7.3%.

In other words, using the Section 351 exchange is expected to have the highest after-tax return (7.3%), while simply doing nothing would have the second-highest (7.0%) and reallocating to the ETF portfolio without the Section 351 exchange would have the lowest return in this scenario (6.7%).

As the example above shows, a Section 351 exchange can add after-tax value over other alternatives in some scenarios. However, the relative benefit depends on the investor's tax situation. The lower the potential tax impact of reallocating into a new portfolio through selling outright, the less of a relative advantage of using a Section 351 exchange. If the embedded gains in the example above hadn't been so high, or if Libby had been in the 15% capital gains tax bracket instead of the 23.8% bracket, the relative advantage of the Section 351 exchange would have been much smaller.

Additionally, if Libby has charitable goals, she might benefit more from donating her most highly appreciated securities to charity, a donor-advised fund, or a charitable remainder trust. These strategies could give her a tax deduction for the charitable contribution, along with avoiding the recognition of gains on the portfolio.

Scenario 2: "De-Risking" A Concentrated Portfolio

As mentioned earlier, a portfolio isn't eligible for tax-deferred treatment in a Section 351 exchange if any single holding constitutes more than 25% of the portfolio, or if the top five holdings make up more than 50%. This means that, for example, a single large stock holding can't be moved to an ETF and diversified without recognizing any gain on the sale.

However, investors may still be able to partially diversify a concentrated position, if they have other assets to contribute to the ETF that meet the 25/50 diversification rule.

Example 2: Yuni bought $15,000 of Apple stock in 2008 for $3.50 per share. Today her Apple shares are worth $1 million, with the same cost basis of $15,000. In addition to the Apple stock, Yuni owns $1 million in an S&P 500 index ETF, meaning her portfolio currently consists of 50% Apple stock and 50% of the S&P 500 ETF.

Yuni cannot transfer her Apple stock into an ETF via a Section 351 exchange, nor can she transfer her entire combined portfolio (including the S&P 500 ETF), since that would violate the 25/50 diversification rule.

However, she could transfer a portion of her Apple stock, along with enough of the S&P 500 ETF to meet the diversification requirements (since, as noted earlier, ETFs are viewed on a "look-through" basis for Section 351 exchanges, meaning that their underlying holdings are used to determine whether they meet the 25/50 diversification tests).

To satisfy the 25/50 diversification test, Yuni transferred 33% ($333,333) of her Apple stock, plus all $1 million of her S&P 500 ETF into a new ETF. This way, her Apple stock makes up $333,333 ÷ $1,333,333 = 25% of the new portfolio (ignoring for this example the likelihood that the S&P 500 ETF would also contain Apple stock, which would lower the amount of individual Apple shares she could contribute).

After the exchange, Yuni still holds $666,667 of Apple stock outside the newly created ETF, which consists of $333,333 (25%) in Apple stock and $1 million (75%) in a diversified mix of stocks from the S&P 500 ETF.

If the new ETF that was seeded via the Section 351 exchange became an S&P 500 ETF itself, then Yuni's overall portfolio would consist of $666,667 (33%) of directly held Apple stock outside the ETF, and $1,333,333 (67%) of S&P 500 stocks inside the newly seeded ETF.

Though she hasn't fully diversified her Apple concentration, she has taken a bite out of it (no pun intended).

But the key thing to note here is that a Section 351 exchange can go some way toward diversifying out of a concentrated position, even if it can't diversify the entire thing.

Section 351 exchanges present a new opportunity for advisors to help clients reallocate or de-risk their portfolios in a tax-efficient way, particularly when those portfolios are 'locked up' due to high embedded gains and little or no losses to harvest.

That said, the tax benefits of Section 351 exchanges can only be realized if they're done correctly. This means that the transferred portfolio must meet the 25/50 diversification rules; the portfolio assets can generally only include stocks, bonds, and other ETFs; and the exchange can only be made to a newly created ETF that will accept in-kind 'seeding' contributions.

Additionally, since Section 351 exchanges primarily serve to reduce the tax friction when reallocating to a more suitable portfolio, it's crucial to evaluate whether the ETF being used for the exchange is actually a good investment. Key questions advisors can consider:

- Who will be managing the ETF?

- What is the ETF's investment objective?

- If the ETF is actively managed, what is the investment thesis?

- Does the ETF sponsor have any history of seeding funds via Section 351 exchange?

- What are the fund's costs and expense ratio?

All of these are questions advisors can ask to help ensure the potential benefits of a Sectio n351 exchange (tax-deferred reallocation and ongoing tax efficiency of the ETF structure) outweigh the risks and costs (higher expenses, tracking error while reallocating the ETF to its investment objective, and the possibility of taxable income and/or IRS examination if the ETF sponsor doesn't manage the Section 351 exchange properly).

Finally, it's important to consider other strategies that might be available, including charitable donations, donor-advised funds, or charitable remainder trusts for individuals who plan to donate some or all of the portfolio to charity.

But for those who plan to use funds from their portfolio (or simply want to maximize what they leave to their heirs), a Section 351 exchange can be a powerful tool – particularly for investors who are in need of reallocating their portfolio and who would otherwise pay significant taxes when transitioning their portfolio. At which point advisors can help their clients explore the options for ETFs that are (or will soon be) open to in-kind seeding, or consider launching their own ETFs to give clients their own customized option for 'rescuing' their locked-up portfolios!

Leave a Reply