Executive Summary

Passed in December of 2019, the SECURE Act brought several changes to the rules governing retirement accounts, the most significant of which (at least for financial advisors and their clients) was the elimination of the ‘stretch’ provision applicable to most non-spouse Designated Beneficiaries of inherited retirement accounts. Instead of letting such beneficiaries stretch distributions out based on their own lifetimes, inherited retirement accounts under the SECURE Act must now be emptied by the end of the 10th year after the year of death. Which is challenging when planning for retirement account beneficiaries… but is especially impactful for so-called “Conduit” Trust beneficiaries.

A Conduit Trust is a particular type of “See-Through” Trust that can serve as the (stretch) beneficiary of a retirement account. In order to be a Conduit Trust, all distributions from an inherited retirement account received by the trust must be passed out (i.e., “conduited”) to the trust beneficiaries each year. The appeal of a Conduit Trust is that beneficiaries named as a sole Income Beneficiary are essentially treated as if they were named directly on the account beneficiary form (i.e., allowing the trust to still take advantage of the ‘stretch’ provision if that conduit beneficiary is an Eligible Designated Beneficiary). However, Conduit Trusts whose conduit beneficiaries don’t meet the new “Eligible" Designated Beneficiary requirements – or have multiple Income Beneficiaries where at least one Income Beneficiary is not considered an Eligible Designated Beneficiary – can face significant new complications under the SECURE Act.

For Conduit Trusts with at least one Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary, the ‘stretch’ provision is automatically eliminated and all funds from inherited retirement accounts must be distributed by the end of the 10th year after death! Accordingly, these circumstances with Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, in particular, beg the question as to whether Conduit Trusts subject to the 10-Year Rule are even a viable solution for clients, especially in cases when the trust language limits distributions to “only” the Required Minimum Distribution. In such scenarios, no distributions can be made until the 10th year after death, when the entire account must be emptied all at once, since that is the only point during the 10-Year Rule when a distribution is actually required (resulting in a potentially huge tax liability in the process).

To help clients address the SECURE Act’s impacts on Conduit Trusts, advisors can start by taking a comprehensive inventory of all clients with trusts as retirement account beneficiaries and identifying those that are Conduit Trusts (which may require some legwork in attaining trust documents to review the trust language regarding distributions). The next step involves identifying all Income Beneficiaries of Conduit Trusts to assess whether the trust can still ‘stretch’ distributions (e.g., is the Income Beneficiary an Eligible Designation Beneficiary? If there is there more than one, are any Income Beneficiaries Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries?). Advisors should then proactively review with clients the implications of the 10-Year Rule on their estate planning strategies.

If an alternative to a Conduit Trust is deemed beneficial, the most straightforward alternative may be creating a new Discretionary Trust to replace the Conduit Trust as the retirement account’s Designated Beneficiary. While this route maintains post-death control over retirement assets, it comes at a potentially high cost, though, as Trust tax rates reach the 37% rate at just $12,950 (in 2020), versus $518,400 (Single) or $622,050 (Married Joint) for Individual taxpayers. Alternatively, Conduit Trusts can simply be replaced by the individual Income Beneficiaries themselves as the named beneficiaries of the retirement accounts.

Ultimately, the key point is that Conduit Trusts can be significantly impacted under the SECURE Act, especially when those Trusts have multiple beneficiaries, and even more so when at least one of those beneficiaries is a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary. Because with the 10-Year Rule in place, these trusts will potentially be required to distribute all retirement account assets on a 10-year schedule, after which they would no longer protect the retirement assets that they were designed to protect in the first place. Which makes it absolutely crucial to review, update, or potentially replace Conduit Trust beneficiaries of inherited retirement accounts… before the retirement account owner passes away, and the (potentially unfavorable) Conduit Trust rules are permanently locked in!

Just as 2019 was coming to a close, Congress brought the SECURE Act, which had previously been placed in a legislative ‘suspended animation’ of sorts by the Senate, back to life by attaching it to a year-end appropriations bill that ‘had’ to be passed in order to avoid another Federal government shutdown.

The new law introduced the largest set of direct changes to the rules governing retirement accounts since the Pension Protection Act of 2006. But for many advisors and their clients, the single most impactful provision of the SECURE Act was its elimination of the ‘stretch’ provision as an option for most non-spouse Designated Beneficiaries of inherited retirement accounts.

Replacing the ‘stretch’ IRA (or stretch 401(k)), in many instances, is a new 10-Year Rule, which requires that an inherited retirement account be emptied by the end of the 10th year after the year of death. And while this change is sure to impact many beneficiaries – regardless of age, the size of their inherited IRA (or other retirement account), or their income tax bracket – there is, perhaps, no single group of beneficiaries that will be impacted to a greater degree than Conduit See-Through Trusts.

As a result of the SECURE Act’s changes, many existing trusts will create tax bombshells or will no longer be able to protect assets after the end of the 10th year after the year of the retirement account owner’s death… or worse – both!

Post-Death Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) Rules After The SECURE Act

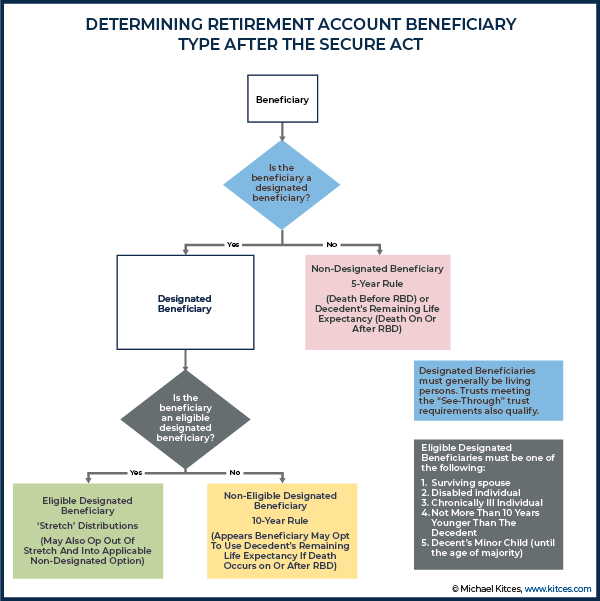

Prior to the SECURE Act, beneficiaries of IRAs and other retirement accounts fit into one of two broad categories: Non-Designated Beneficiaries, and Designated Beneficiaries.

Non-Designated Beneficiaries, such as charities, estates, and trusts which failed to qualify as See-Though Trusts (discussed further below), were ‘forced’ to distribute the proceeds of an inherited IRA or other retirement account by the end of the fifth year after the owner’s death if death occurred prior to the decedent’s Required Beginning Date (RBD). Conversely, if death occurred on or after the decedent’s RBD, the same funds had to be distributed over the deceased owner’s remaining Single Life Expectancy. Which effectively meant the trust would either be obligated to distribute the retirement account out after 5 years, or over the life expectancy of a decedent that might not have been much longer than 5 years (as by definition, a decedent past his/her Required Beginning Date would be in their 70s, 80s, 90s, or even older!).

Notably, the SECURE Act made no direct changes to these rules. (Though such beneficiaries may be indirectly impacted, however, by the SECURE Act’s ‘pushing back’ of the ‘regular’ RBD date from April 1st of the year following the year the retirement account owner’s 70 ½ ‘birthday’ to April 1st of the year after the owner’s 72nd birthday. Which ironically prolongs the period before the account owner’s RBD, and consequently creates even more of a chance that the five-year distribution schedule would be triggered when the owner dies before their RBD).

But while the rules for Non-Designated Beneficiaries have essentially remained unchanged, the SECURE Act dramatically changed the rules for Designated Beneficiaries. Such beneficiaries, generally defined as living persons (although certain See-Through Trusts, as discussed further below, also qualify), were previously able to ‘stretch’ distributions over their life Single Life Expectancy. The SECURE Act, however, bifurcated the old group of Designated Beneficiaries into two separate groups of its own: Eligible Designated Beneficiaries and Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries.

The good news for fans of the ‘stretch’ is that Eligible Designated Beneficiaries can still take advantage of that benefit. The bad news is that the list of Eligible Designated Beneficiaries is extremely limited as, in order to be an Eligible Designated Beneficiary, the beneficiary must be one of the following:

- Surviving spouse;

- Disabled person;

- Chronically ill person;

- Individuals within 10 years of the deceased retirement account owner’s age; or

- A minor child of the decedent.

It’s hardly an extensive list. Not to mention that beneficiaries in the last group – minor children of the decedent – are only considered Eligible Designated Beneficiaries until they reach the age of majority!

And what about those otherwise “Designated” Beneficiaries who don’t fall into one of the categories listed above? Under the SECURE Act, they become what are now commonly being referred to as Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (though technically, there is no such term, and they are just “Designated Beneficiaries” who are not “Eligible Designated Beneficiaries”), and face the brunt of the SECURE Act’s changes to the rules on post-death Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs).

More precisely, such beneficiaries are subject to the SECURE Act’s new 10-Year Rule, which requires that the entire proceeds of the inherited retirement account be distributed by the end of the 10th year after the year of death. So, for instance, a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary who inherits an IRA in 2020 will have to distribute the entire proceeds of the account by the end of 2030.

Notably, there are no RMDs within the period of time covered by the 10-Year Rule for a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary, other than in the final year (the 10th year after the year of death), when the RMD ‘calculation’ is simply “whatever is still left in the account.”

Conduit See-Through Trusts As Beneficiaries of IRA, 401(k), And Other Retirement Accounts

See-Through Trusts that can qualify as Designated Beneficiaries come in two ‘flavors’: Conduit Trusts and Discretionary Trusts.

A Conduit Trust is a See-Through Trust which requires that any distributions from an inherited retirement account to the trust that are made each year be passed right out from the trust to the trust beneficiaries.

Note that this would not include a trust in which the trustee merely has the option (i.e., the “discretion”) to make such distributions and chooses to do so. Rather, a conduit trust is one in which the trustee is given no choice but to distribute from the trust to the trust beneficiaries any distributions the trust received from an inherited retirement account. Any trust which does not meet this rigid requirement is considered a Discretionary Trust (also referred to as an Accumulation Trust), and is subject to other rules.

As noted earlier, while the implementation of the new 10-Year Rule for Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries will have broad impact, some Conduit See-Through Trusts that have been named as the beneficiary of an IRA, 401(k), or other defined contribution retirement account are likely to be hit the hardest. To understand why, though, it is first necessary to have a basic understanding of how See-Through Trusts, and Conduit See-Through Trusts in particular, work.

IRC Section 401(a)(9)(E) defines a Designated Beneficiary as “any individual designated by the employee” (emphasis added). Thus, a plain reading of the Internal Revenue Code requires that a Designated Beneficiary be an actual person (i.e., an individual).

Nevertheless, when Congress wrote the regulations covering this area, they realized that there would have to be some sort of mechanism allowing those needing a trust to be able to receive the more preferable post-death tax treatment afforded to Designated Beneficiaries. And to accommodate that group, the IRS created what are commonly referred to as See-Through Trusts.

Notably, despite not actually being living people, such trusts are eligible for treatment as Designated Beneficiaries (i.e., the trust can ‘see through’ to the underlying trust beneficiaries and use their life expectancies to stretch out required minimum distributions), provided the trust meets four requirements outlined by Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-4, Q&A-5. They are:

- The trust must be valid under state law;

- The trust must be irrevocable upon the account owner’s death;

- All applicable (more on this below) trust beneficiaries must be identifiable; and

- A copy of the trust, or a certified list of trust beneficiaries, must be provided to the IRA custodian, or plan administrator, by October 31st of the year following the account owner’s death.

In addition to the four requirements listed above, there is an unwritten requirement that all applicable trust beneficiaries must be Designated Beneficiaries (individuals). Because if not, the trust will “look through” to a beneficiary with no life expectancy and be in the same situation as if the trust did not meet the See-Through Trust rules to begin with.

If, however, a trust meets each of the above requirements, and all of the applicable trust beneficiaries are Designated Beneficiaries, then the trust, itself, is eligible to be treated as a single Designated Beneficiary. Thus, prior to the SECURE Act, such trusts were able to ‘stretch’ distributions using the (oldest) applicable trust beneficiary’s life expectancy.

After the SECURE Act, though, some Conduit Trusts whose beneficiaries are, themselves, Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, will be able to continue to ‘stretch’ distributions while other Conduit Trusts will be stuck with the 10-Year Rule.

Key Rules Of Conduit Trusts

One of the key benefits of a Conduit Trust is that for the purpose of identifying beneficiaries (rule #3 for a trust to be a See-Through Trust) to determine the beneficiary with the shortest distribution schedule, only the Income Beneficiaries of the Conduit Trust must be evaluated.

The Income Beneficiaries of the Conduit Trust are the first group of trust beneficiaries who are entitled to receive the distributions from the Conduit Trust until they die. Future beneficiaries entitled to receive any remaining trust assets after the passing of the income beneficiaries can be disregarded for purposes of determining the inherited retirement account distribution schedule, as they are considered ‘mere successor beneficiaries’ of the original Income Beneficiary.

Example 1: Jerry named a Conduit Trust as his IRA beneficiary prior to his death. The terms of the Conduit Trust provide that distributions from the trust shall be distributed to Jerry’s brother, who is 5 years younger. It further provides that upon Jerry’s death, any remaining trust assets shall be held in trust for Jerry’s nieces, who are both adults.

Given these facts, Jerry’s conduit trust will be able to ‘stretch’ distributions using Jerry’s brother’s Single Life Expectancy (because he is less than 10 years younger than Jerry, and is an Eligible Designated Beneficiary). Notably, despite the fact that Jerry’s nieces (the Remainder Beneficiaries) are adults, and are not Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, they will not impact the stretch distribution schedule of the Conduit Trust (because as a Conduit Trust, only the income Beneficiary’s (Jerry’s brother’s) age is considered).

Example 2: Harris named a Conduit Trust as his IRA beneficiary prior to his death. The terms of the Conduit Trust provide that at least all required minimum distributions from the trust shall be distributed to Harris’s two healthy adult children as received each year. It further provides that each of Harris’s children may appoint, via their Will, who shall receive any remaining portion of their share of trust assets upon their passing.

Despite the fact that Harris’s children, in their Will, could name anybody, or anything (e.g., a charity), as the successor to their portion of trust assets remaining at their death (which means those successor beneficiaries are decidedly not identifiable and thus wouldn’t qualify to stretch), they will not impact the stretch distribution schedule of the Conduit Trust.

The income beneficiaries of Harris’s Conduit Trust - the only beneficiaries whose life expectancies matter for purposes of determining the post-death distribution rules) are his healthy adult children (who are themselves Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries because they’re not minor children but are more-than-10-years-younger than Harris). And as a result, Harris’s Conduit Trust will not be a Non-Designated Beneficiary (subject to the 5-year rule), but will only be able to utilize the 10-Year Rule for Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (and not a full life expectancy stretch).

Since Conduit Trusts require all distributions received from an inherited retirement account to be passed right out to trust beneficiaries, they also eliminate the potential for those distributions (from inherited retirement accounts) to get stuck inside a trust, which would cause them to be taxable at trust income tax rates. This year (2020), trusts reach the highest Federal income tax bracket at $12,950 of taxable income, whereas Joint Filers don’t reach the same 37% until they have $622,050 of taxable income ($518,400 for Single Filers).

Conduit Trusts force the almost-always-favorable taxation at a trust beneficiary’s own personal income tax rate, but at the expense of a loss of control (since amounts distributed from the trust are no longer protected by it).

Discretionary trusts, on the other hand, often result in assets being held within the trust, and subject to trust income tax rates, either because the trust requires such action, or because the trustee has chosen to do so in order to preserve the protection afforded by the trust.

SECURE Act’s Impact On Conduit Trusts

Prior to the SECURE Act’s passing, Conduit Trusts were eligible to ‘stretch’ distributions over the (oldest) income beneficiaries’ life expectancy (as long as all the beneficiaries were themselves Designated Beneficiaries). After the SECURE Act, though, treatment for Conduit Trusts will vary, depending upon the treatment of the underlying income beneficiary (or beneficiaries). There are a variety of possibilities, some of which have clear outcomes given the SECURE Act’s changes, and some of which are a bit greyer and open for debate.

Conduit Trust With A Single Income Beneficiary

The simplest and most straightforward possible beneficiary configuration for a Conduit Trust is one with just a single income beneficiary. In such situations, the Conduit Trust will be able to ‘look through’ the trust to the Income Beneficiary.

However, qualifying for See-Through treatment as a Conduit trust for a Designated Beneficiary will no longer ensure a stretch. If the Income Beneficiary is a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary (i.e., not one of the five specified groups of individual beneficiaries treated as such), then the trust will be subject to the 10-Year Rule. (Which is better than the 5-year rule for a Non-Designated Beneficiary, but still not a full life expectancy ‘stretch’.)

By contrast, if the Income Beneficiary of the Conduit Trust is an Eligible Designated Beneficiary, then the trust will be able to ‘stretch’ distributions over the Eligible Designated Beneficiary’s life expectancy.

In each instance, the single Conduit Trust Income Beneficiary is treated the same as if they had been named directly on the account beneficiary form (which is the whole point of using a Conduit Trust in the first place).

Example 3: Nina is the sole Income Beneficiary of a Conduit Trust. Nina is the 60-year-old girlfriend of Cliff, who was 64 years old when he died in February 2020. Since Nina was within 10 years of Cliff’s age, she is an Eligible Designated Beneficiary.

Since Nina is the sole beneficiary of a Conduit Trust, the trust will be able to ‘stretch’ distributions over her lifetime until her passing (upon which ‘stretch’ distributions would terminate, and the 10-Year Rule would be triggered for subsequent distributions from the IRA to the trust).

For Conduit Trusts with a single Eligible Designated Beneficiary named as the Income Beneficiary (such as the one established for the benefit of Nina in Example 3, above), it’s pretty much ‘business as usual’ for planning purposes after the SECURE Act.

The problem, however, is that a substantial number of Conduit Trusts will not fit this fact pattern, which will likely result in the application of the 10-Year Rule.

Conduit Trust With Multiple Income Beneficiaries Who Are All Eligible Designated Beneficiaries

Another possible scenario is a Conduit Trust with multiple Income Beneficiaries, all of whom are Eligible Designated Beneficiaries. In these cases, the post-death RMD rules in such situations are not clear.

Some practitioners have suggested that if the trust splits into sub-trusts immediately after death, that each sub-trust would be able to use the sub-trust beneficiary’s age to determine life expectancy.

Others have suggested that such trusts cannot qualify for treatment as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary, period and, thus, would not be able to ‘stretch’ distributions. Because ironically, the rules interpreted literally only permit an Eligible Designated Beneficiary to stretch… not necessarily a group of Eligible Designated Beneficiaries.

However, in this author’s opinion, both interpretations are unlikely outcomes.

With regard to the former, the IRS has long denied sub-trusts the ability to use only the life expectancy of the sub-trust beneficiary to determine life expectancy when calculating the post-death distribution schedule when the ‘master trust’ has been named on the beneficiary form. In fact, in recognition of this very interpretation, the SECURE Act codified an exception to this ‘rule’, but only with respect to certain sub-trusts benefiting disabled and/or chronically ill persons. Given the specificity with which Congress crafted that provision, limiting its benefit only to disabled and/or chronically ill persons, it seems unlikely they intended for it to have universal application to all sub-trusts.

And with regard to the latter, Conduit-style See-Through trusts have long been able to have multiple Designated Beneficiaries named as Income Beneficiaries, and that has never stopped them from being able to ‘stretch’ distributions over the oldest of those life expectancies before. It would seem odd for the IRS to suddenly interpret that differently now when today’s post-SECURE Act Eligible Designated Beneficiaries are essentially equivalent to ‘yesterday’s’ pre-SECURE Act Designated Beneficiaries.

As such, this author believes that the most likely result is that a Conduit Trust will be required to distribute assets over the shortest distribution period that would be applicable to any of the Conduit Trust’s Income Beneficiaries. Admittedly, though, the problem with this interpretation is that while the shortest distribution period is clear in some situations, it is anything but in others.

Suppose, for instance, that a Conduit Trust has 3 minor children as beneficiaries. It is would seem reasonable to believe (and follows previous IRS interpretations of Conduit Trusts) that the Trust would be stuck using the oldest minor child’s life expectancy to distribute assets. That would both create the highest ‘stretch’ distributions (during the period of time when the oldest child was still a minor), and require the trust to ‘switch’ to the 10-Year Rule at the earliest possible time (when the oldest child reached their age of majority).

Suppose, though, that the two Income Beneficiaries of a Conduit Trust are the IRA owner’s 55-year-old brother, who is an Eligible Designated Beneficiary because he was only 3 years younger than the IRA owner (so he meets the within-10-years requirement for an Eligible Designated Beneficiary), along with the IRA owner’s 15-year-old minor child. The 55-year-old is clearly older, and thus, the ‘stretch’ RMDs would be higher using his age. On the other hand, though, the 15-year-old minor will reach the age of majority no later than when he reaches age 26, which should trigger the 10-Year Rule (far earlier, in most cases, than it would be triggered by the 55-year-old’s death).

So, what do we do? Should we use the 55-year-old’s age to calculate RMDs until he dies? Do we use the minor child’s age the whole time? Or maybe we start with the 55-year-old brother’s age until the child reaches the age of majority, and then switch to the 10-year rule? That would seem to be the ‘fairest’ way to deal with the situation, but there’s no guarantee that the IRS will view things the same way.

Frankly, there is no precedent for starting to calculate RMDs using one person’s life expectancy, and then switching to using another person’s life expectancy midway.

Given the ambiguity surrounding Conduit Trusts with multiple Eligible Designated beneficiaries as Income Beneficiaries (especially in situations like the one described above), some practitioners have suggested that where the ‘stretch’ is desired and potentially possible (e.g., there is at least one Eligible Designated Beneficiary), Conduit Trusts should be drafted with only a single Income Beneficiary. Thus, if there are multiple desired Eligible Designated Beneficiaries to be named as Income Beneficiaries of a Conduit Trust, multiple Conduit Trusts should be drafted in order to allow each Trust to house just a single such beneficiary.

Despite the potential added costs and complexities associated with the use of multiple trusts, given the uncertainty surrounding the treatment of Conduit Trusts with Multiple Beneficiaries, this would seem to be a reasonable and prudent decision.

Conduit Trust With At Least One Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary

A final situation, and one in which the impact of the SECURE Act’s changes is most apparent, is when a Conduit Trust has one or more Income Beneficiaries who are Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries.

In such scenarios, the presence of even a single Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary will definitively spoil the ‘stretch’ for the Conduit Trust (as the general least-favorable-life-expectancy rule with multiple beneficiaries forces all beneficiaries to use the Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary’s least-favorable treatment). And as a result, the trust will have to liquidate all funds from any inherited retirement accounts (of which it is the beneficiary) by the end of the 10th year after death… and because it’s a conduit trust, will then have to conduit all of those assets through to the beneficiary themselves!

Example 4: An IRA owner died on January 5, 2020, leaving his IRA to a Conduit Trust. The Income Beneficiaries of the Conduit Trust are his 14-year-old daughter Roy, and his 26-year-old daughter Sky (who has reached the age of majority).

Although Roy is an Eligible Designated Beneficiary, the presence of Sky, who is not an Eligible Designated Beneficiary, means that the trust will have to distribute assets using the 10-Year Rule.

But while the rule here may be clear, there’s a question as to whether Conduit Trusts, regardless of who are named as Income Beneficiaries, that are subject to the 10-Year Rule will even make sense as a planning option in the first place. Candidly, the answer, in many (and likely most) situations, is probably “no”.

(Nerd Note: There is a possible technical exception to this rule, which exists mostly in theory, but has little to no practical application. The SECURE Act created something known as an “Applicable Multi-Beneficiary Trust”, which can allow a disabled and/or chronically ill beneficiary to ‘stretch’ their portion of retirement assets inherited via a trust, even if there are other Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries named as trust beneficiaries that would normally spoil the ‘stretch’. However, trusts for disabled and/or chronically ill persons should rarely, if ever, be drafted as Conduit Trusts, because the forced distribution of assets from the trust to such a beneficiary could easily impair, or cause the loss of, means-tested programs, such as SSI, SSDI, and Medicaid.)

Conduit Trusts Subject To The 10-Year Rule Are Extremely Problematic

As discussed above, while there are a variety of situations in which a Conduit Trust will continue to be able to ‘stretch’ distributions, in the event there is at least one Income Beneficiary that is a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary, it is best (and reasonable) to assume that the 10-Year Rule will apply.

In such situations, the entire inherited retirement account left to the trust will have to be distributed, not just from the IRA to the trust, but also from the trust to the underlying beneficiary, by the end of the 10th year after death. When combined with the rules for Conduit Trusts, this creates a best-case scenario and a worst-case scenario, neither of which is actually very good.

Conduit Trusts Subject To The 10-Year Rule: Best-Case Scenario

The primary requirement of a Conduit Trust is that any inherited retirement account distributions received by the trust must be immediately passed out to the trust beneficiaries. The Internal Revenue Code provides the rules for how slowly this can be done (e.g., the 10-Year Rule). The Conduit Trust’s own language, on the other hand, dictates how quickly it can be done.

For instance, a Conduit Trust can be drafted in such a manner as to allow the trustee to accelerate distributions from the inherited retirement account at the Trustee’s discretion. Presumably, such authority could allow (but not require) the trustee to distribute all of the funds from the inherited retirement account immediately (which would, in turn, result in an immediate distribution of those assets from the Conduit Trust to the Income Beneficiaries).

Such a Conduit Trust might include language that says something like:

The Trustee shall withdraw from any Inherited Retirement Account the Required Minimum Distribution for such Retirement Account each year.

The Trustee is also authorized to take distributions in excess of the Required Minimum Distribution, provided such distributions are, in the Trustee’s sole discretion, for the sole benefit of [INCOME BENEFICIARY’S NAME].

All amounts withdrawn from any retirement account, net of applicable trust expenses, shall be distributed to [INCOME BENEFICIARY’S NAME] as soon as administratively practicable.

Such language probably creates the best-case scenario for a Conduit Trust subject to the SECURE Act’s new 10-Year Rule because it affords the trustee the flexibility of accelerating distributions from the inherited retirement account to help manage the tax consequences.

If, for instance, the trustee determines there are no contraindications to accelerating distributions (e.g., looming creditor issues, spendthrift issues, etc.), the trustee may decide to spread distributions out over the period of time covered by the 10-Year Rule. Since those distributions are immediately passed out to the Income Beneficiary of the Conduit Trust, this would help the beneficiary manage the ultimate impact of the distributions on their personal income tax return.

This, again, is the best-case scenario. But it’s still not all that great. Why?

Because the 10-Year Rule still provides the Internal Revenue Code’s drop-dead date for distributions from the inherited IRA of December 31st of the 10th year after the year of death.

Accordingly, even in the best-case scenario, the entire inherited retirement account is still emptied within the 10 years after death. And because the Conduit Trust requires all of those distributions to be passed right out to the Income Beneficiary, it means the trust, itself, is empty (and, therefore, useless!) by the end of the 10th year after death.

Very few retirement account owners are likely to see the value of spending money to draft and administer a trust that is only going to protect assets for 10 years… at most! And it may not even be effective protection, if creditors of the beneficiary realize that the trust assets will become available in a ‘foreseeable’ time period!

Conduit Trusts Subject To The 10-Year Rule: Worst-Case Scenario

While a Conduit Trust like the one described above may no longer seem like a good deal after the SECURE Act, it’s far from a worst-case scenario. That dubious distinction will, instead, fall to less flexible Conduit Trusts.

More specifically, in the past, some Conduit Trusts were drafted in a manner that essentially forced the ‘stretch’ upon beneficiaries. They included language that read something similar to the following:

The Trustee shall withdraw from any Inherited Retirement Account only the Required Minimum Distribution for such Retirement Account each year.

All such amounts, net of applicable trust expenses, shall be distributed to [INCOME BENEFICIARY’S NAME] as soon as administratively practicable.

If a Conduit Trust is subject to the 10-Year Rule and includes a provision similar to the one above, the trustee’s hands are essentially tied. They will not be able to take any distributions from the inherited IRA until the 10th year after death.

Because, as noted earlier, when the 10-Year Rule applies, there are no required minimum distributions until the 10th year after death. Thus, a trust that says “take only the required minimum distribution” is literally prohibiting the trustee from taking any distribution from the inherited retirement account until that 10th year after death.

That means that none of the account can be distributed… until the end, when the entire inherited retirement account, plus any growth, will all have to come out in one tax year – a likely tax disaster.

Example 5: Stone died on February 10, 2020, leaving his $2 million IRA to a Conduit Trust for the Benefit of his two adult children.

Stone’s Conduit Trust was drafted prior to the passage of the SECURE Act and was intended to ensure his children ‘stretched’ his IRA. As such, the trust includes language requiring the trustee to take only the RMD each year and to pass such RMDs immediately out to his two children in equal shares.

Given the nature of Stone’s Conduit Trust, there will be no distributions to the trust in the year of his death, or in the following nine years. Then, in the 10th and final year of the period of time covered by the 10-Year Rule – the only year in which there is an RMD – the trustee will be required to distribute the entire inherited retirement account. And as a Conduit Trust, that full amount will have to be immediately passed along to the Income Beneficiaries.

Assuming a 7% annual rate of return and using the ‘Rule of 72’, we can roughly approximate a doubling of the inherited retirement account by this time. That would result in a distribution of $4 million, totally liquidating the inherited IRA, and a $2-million-income hit to each of Stone’s children, as Income Beneficiaries of the trust, all at once in the 10th year after the year of death.

Accordingly, Stone’s trust is useless by the end of the 10th year after his death (just as would be the case in even the best-case scenario, described earlier). But on top that, his beneficiaries are stuck with a massive income hit that will virtually guarantee that the overwhelming majority of their inheritance will be subject to the top Federal income tax rate at the time.

For most scenarios like the above, the words “absolute tax disaster” would probably be putting it mildly.

(Nerd Note: While a minor child of a deceased retirement account owner is an Eligible Designated Beneficiary, it’s important to note that such an Eligible Designated Beneficiary status only exists until the minor reaches the age of majority. Thus, while a Conduit Trust established for the benefit of a minor child will not be subject to the 10-Year Rule immediately, it will become subject to that rule at some point in the future. Thus, for such trusts, the same Conduit Trust problems outlined may exist, only with slightly delayed application.)

An Advisor’s Game Plan For Post-SECURE Act Conduit Trusts

Clearly, the SECURE Act’s new 10-Year Rule has dramatic, and potentially disastrous, ramifications when applied to Conduit Trusts. With that in mind, it’s worth exploring some steps advisors can take now to make sure that the words “absolute disaster” stay as far away from their clients’ plans as possible.

Inventory Clients’ Beneficiaries To Create A Prioritized To-Be-Contacted List

The first step in addressing the SECURE Act’s impact on Conduit Trusts is to know who has named a trust as a beneficiary of their retirement account in the first place! As such, advisors who do not currently have a “Master List” of client beneficiaries should consider making such a list.

Additionally (and preferably), clients’ beneficiaries can be added to an Advisor’s Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system (if such information is not already stored in such a manner), and a report can be pulled to identify clients with trusts named as their beneficiary.

Once all trusts have been identified, it is then necessary to determine which trusts are Conduit Trusts. Hopefully, copies of any such trusts (or clients’ Wills that create such trusts upon a client’s passing) are already on file. If so, advisors can look at the trust’s language regarding distributions to see if it requires amounts received by the trust to be passed right out to the trust beneficiaries; if it does, then the trust is a Conduit Trust.

Where copies of legal documents are not readily available, or in situations where the advisor cannot discern from the trust’s language whether it is a Conduit Trust or not, it may become necessary to reach out to the client’s legal advisor (which will often necessitate coordinating with the client) to find out.

Once Conduit Trusts have been identified, the next step is determining the SECURE Act’s direct impact on the trust’s ability to ‘stretch’ distributions. In other words, does the trust have only a single Eligible Designated Beneficiary, such as a spouse, as the Income Beneficiary (in which case the ‘stretch’ is still available and immediate outreach is less critical), or some other beneficiary (or combination thereof) that includes a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary which will trigger the application of the SECURE Act’s new 10-Year Rule?

In identifying the highest-priority discussions (which clients to contact first to discuss the SECURE Act’s impact), advisors should give preference to situations where clients have named a Conduit Trust that will be subject to 10-Year Rule as their Primary Beneficiary.

Discussions with clients who have named such trusts as a Contingent Beneficiary are less urgent, but should not be ignored, particularly where such trusts have a high likelihood of eventually holding inherited retirement assets (e.g., after the death of both the retirement account owner and their spouse).

Reevaluate The Trust-As-Beneficiary Decision And Consider The Use Of A Discretionary Trust Instead?

Once the highest-priority conversations have been identified, advisors should engage clients in meaningful discussions to help them understand the SECURE Act’s impact on Conduit Trusts (and particularly those subject to the 10-Year Rule). Specifically, advisors should emphasize the fact that, even in best-case scenarios, such trusts will offer no protection beyond the end of the 10th year after their year of death for any retirement assets left to the trust (not to mention the potential tax impact of accelerated distributions or the tax disaster of having them all liquidate from the IRA and trust together in the 10th and final year).

Given the strong likelihood that the loss of protection after 10 years will not satisfy a client’s initial goals when establishing a conduit trust (which is typically to create some barriers between the beneficiary and the money payable into the trust in the first place), alternatives will need to be explored.

If maintaining post-death control (e.g., ensuring the path of successor beneficiaries, maintaining creditor/divorce protection of account proceeds, etc.) over retirement assets for a period longer than 10 years after death is of significant importance to a client, the best (and potentially only) way to do so will be to create a new (discretionary) trust and to designate this new trust as the beneficiary of the retirement account (instead of the Conduit Trust), that will allow (or require) the trustee to hold assets within the trust after they are distributed from the inherited retirement account.

Advisors should point out that any amounts retained by such a trust will be subject to trust income tax rates, which, as noted earlier, are extremely inefficient (because they get to the highest 37% rate at just $12,950 in 2020). This, unfortunately, will be the cost (or at least part of the cost) of the desired post-death control.

Alternatively, some clients may decide that in light of the added costs – predominantly higher income taxes associated with the use of a discretionary trust which retains distributions from a retirement account – perhaps scrapping the trust and naming the trust beneficiaries as direct beneficiaries of the retirement account instead, so that they inherit the money directly, is the better option.

There simply is no one-size-fits-all answer. But at the end of the day, it does generally boil down to a singular question...

Which is more important: minimizing the cost and complexity associated with the plan, or maintaining control over the assets after death?

It’s a ‘simple’ question, but one which may not have a simple or readily apparent answer. Ultimately, while the decision of “to use a trust or not” is one that should involve an estate planning attorney as well, helping to walk a client through the advantages and disadvantages of each approach in easy-to-understand language may be one of the most valuable services an advisor can provide to clients trying to grapple with this decision.

Reformation And Decanting – Proposed Techniques As Potential Strategies For Already-Funded Conduit Trusts Subject To The 10-Year Rule To Retain Assets

The SECURE Act was enacted on December 20, 2019, and its effective date for most retirement assets is on January 1, 2020. That means that Congress gave many retirement owners less than two weeks to absorb the SECURE Act’s changes, identify planning strategies to deal with those changes, and implement such changes… all before a massive shift in rules that had existed for more than 30 years would become effective, upending potentially decades-old planning.

Of course, if a retirement account owner hasn’t actually passed away yet, there’s always time to change the beneficiary designation to a new trust (or other beneficiary). However, once the retirement account owner dies, the beneficiary of the account is ‘locked in’.

Which means, unfortunately, given this compressed period of time, it’s possible that individuals may have passed away shortly after the new year in 2020, and before having a chance to update their beneficiary designations… leaving IRA, 401(k), or other SECURE-Act-affected retirement benefits to 10-Year-Rule-burdened Conduit Trusts.

One option to address such situations is to have the trustee seek reformation of such a trust via state court in order to allow the trust to retain assets (i.e., literally re-writing the trust to not make Conduit Trust distributions, under the auspices that it wasn’t really what the original grantor intended). Alternatively, another path is to decanting the trust into another trust that would allow for the same (i.e., moving assets from the Conduit Trust, into another newly-created trust that would, in turn, limit the dollars from actually flowing through to the underlying beneficiary outright).

Notably, both reformation of a trust and the decanting of a trust are legal strategies largely controlled by states (with rules differing rather significantly between various jurisdictions). And while an advisor can help educate clients about what these processes involve and their potential benefits, such techniques should be reviewed with a qualified estate planning attorney. Furthermore, while both of these options might work under state law, there is no guarantee that the IRS will go along with the plan.

In the past, for instance, the IRS has often rejected a post-death reformation of a trust by a state court for purposes of determining the ‘stretch’ period applicable to a trust, such as what happened in its Private Letter Ruling PLR 201021038. Perhaps then, the IRS would take the view that such a reformation – or decanting the trust to a similar end – would result in a violation of the “The trust must be irrevocable at death” rule applicable to See-Through Trusts, which would relegate the trust back to Non-Designated Beneficiary status.

If that were to occur, the reformation/decanting might allow the trust to retain (and therefore protect) assets for beneficiaries beyond the end of the period of time that would be covered by the 10-Year Rule, but at the expense of the even-more draconian post-death distribution rules that apply to Non-Designated Beneficiaries (the 5-year rule, or decedent’s life expectancy if he/she had already passed their Required Beginning Date for the onset of RMDs).

Though on the other hand, where more control, above all else, is ‘needed’, the difference between the trust having to distribute all inherited retirement account assets in 5 years (if death occurred prior to the required beginning date) versus 10 years will be of only minor concern, relative to keeping the assets in trust and not distributing to an irresponsible spendthrift beneficiary.

The SECURE Act’s imposition of the new 10-Year Rule for Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, including Conduit Trusts with one or more such persons named as an Income Beneficiary, represents a dramatic change to the estate planning landscape. In light of these changes, all trusts, but particularly Conduit Trusts subject to this new rule, must be reviewed and likely amended or replaced entirely.

Simply put, the SECURE Act preserves Conduit Trust treatment in the case of Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, but introduces potential complications when one or more Eligible Designated Beneficiary is a minor child… and obliterates most of the value of a Conduit Trust when that the beneficiaries are Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (subject to the 10-Year Rule).

In a best-case scenario, a Conduit Trust subject to the 10-Year Rule will give a trustee the ability to protect assets for trust beneficiaries for up to 10 years (after death of the retirement account owner), but only 10 years, while balancing the potential tax savings that could be achieved by accelerating distributions to the trust (and correspondingly, to trust beneficiaries) in earlier years.

At worst, such a trust will restrict access to any retirement assets until the 10th year after death, at which a single, lump-sum distribution will be passed through the trust and along to the Income Beneficiaries (clustering the entire tax event into a single year and amplifying the adverse tax outcome).

In both scenarios, however, the trust is absolutely useless by the end of the 10th year after death, likely eliminating most of whatever desired protection it was created to provide in the first place.

But the good news is that for most clients, there’s still time to ‘fix’ this potential problem. All that’s required is the updating of a beneficiary form… perhaps to the former-trust beneficiaries directly, or perhaps to a new, discretionary See-Through Trust that will allow the assets to be protected by the trust for many decades.

Finally, where such trusts have already been funded post-SECURE Act, the benefits of more advanced trust planning, such as reformation or decanting, should be evaluated with the help of a qualified legal professional.