Executive Summary

Passed into law in December 2019, the “Setting Every Community Up For Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act”, introduced a plethora of substantial updates to longstanding retirement account rules. One of the most notable changes was the elimination (with some exceptions) of the ‘stretch’ provision for non-spouse beneficiaries of inherited retirement accounts. As prior to the SECURE Act, beneficiaries of inherited retirement accounts were able to ‘stretch’ out distributions based on their own entire life expectancy, but now most non-spouse beneficiaries will be required to deplete their accounts within ten years after the original owner’s death. (Unlike RMDs, though, the new 10-Year Rule offers flexibility around the timing of distributions, as it does not require annual withdrawals – funds can be withdrawn in any amount, at any time over the course of the 10-year term – as long as the entire amount is withdrawn by the end of the 10th year.)

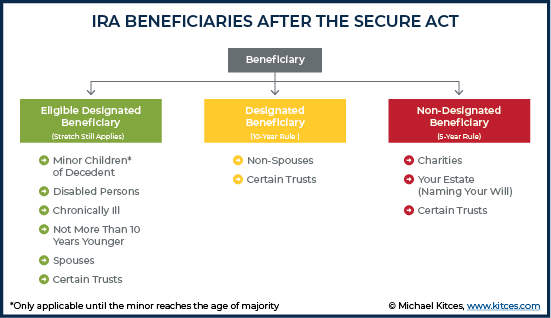

However, not all beneficiaries will be impacted by this new “10-Year Rule”. Instead, the SECURE Act identifies three distinct groups of beneficiaries: Non-Designated Beneficiaries (i.e., non-person entities such as trusts and charities), Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (i.e., individuals who are spouses of account holders, those who have a disability or chronic illness, those not more than 10 years younger than the decedent, minor children of decedents, or “See-Through” trusts), and Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (i.e., any individual who qualifies as a Designated Beneficiary but is not on the list of Eligible Designated Beneficiary).

This distinction matters because Non-Designated Beneficiaries and those who are part of the newly created Eligible Designated Beneficiaries group are generally subject to the same rules prior to the SECURE Act (either the 5-year rule or stretching over life expectancy, respectively), it is the Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries that are now subject to the new 10-Year Rule, from trusts to adult children and more. Fortunately, the 10-year rule does still facilitate at least some flexibility – as the rule simply requires that all funds be distributed by the end of the 10th year after death of the original account owner, but the beneficiary has discretion over when to take the dollars out over that time window – though such a mandatory distribution window may introduce new challenges for certain types of See-Through trusts (where the flexibility eliminates ‘automatic’ annual conduit distributions to beneficiaries and could trigger the sudden liquidation of both the IRA and trust at the end of the 10-year window).

Ultimately, the key point is that, while there are now three distinct groups of beneficiaries under the SECURE Act, only one of these groups (i.e., the Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries) must now contend with the new SECURE Act 10-Year Rule for inherited retirement accounts. For the other two groups (i.e., Eligible Designated Beneficiaries and Non-Designated Beneficiaries), very little has changed for Non-Designated Beneficiaries, and Eligible Designated Beneficiaries still follow the same rules (with few exceptions) as the pre-SECURE Act Designated Beneficiaries.

In December 2019, the retirement planning community was rocked when the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act, which seemed destined to remain stuck in Washington gridlock indefinitely, was whisked back to life and attached to a year-end appropriations package that ‘had’ to be passed to keep the Federal government funded. Within a matter of days, the bill passed the House and the Senate, where it eventually landed on President Donald Trump’s desk and was signed into law on December 20, 2019.

The SECURE Act’s changes to the laws governing retirement accounts, both in terms of sheer volume and impact, are considered by many experts to be the most significant since the passing of the Pension Protection Act of 2006. But while the SECURE Act made plenty of changes to the rules for retirement accounts, such as increasing the starting age for Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs), as well as eliminating the maximum age for Traditional IRA contributions, the headline change for most financial advisors was its new rule eliminating the ‘stretch’ provision for most non-spouse designated beneficiaries. And for good reason…

The SECURE Act’s changes to the post-death rules for retirement account owners have massive implications for many beneficiaries who, as a result of the new rules, will generally have to distribute funds from their inherited account(s) within 10 years after the year of the owner's death… much faster than what previously may have been anticipated.

The changes, however, are perhaps just as disruptive for retirement account owners, themselves, who in light of the SECURE Act’s changes, may wish to revise everything from Roth conversion plans, to exactly who (or what [e.g., a trust or charity]) they name as their beneficiaries to begin with!

How The SECURE Act Changes The Post-Death Distribution Rules For Stretch IRAs, 401(k)s And Other Retirement Accounts

Historically, beneficiaries of IRAs and employer-sponsored defined contribution plans (e.g., 401(k) plans, 403(b) plans, Thrift Savings Plans, etc.) fell into two broad categories: Designated Beneficiaries, and Non-Designated Beneficiaries. The SECURE Act changes this by effectively splitting the pre-SECURE Act group of “Designated Beneficiaries” into two sub-groups of its own; Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, and Designated Beneficiaries who are NOT Eligible Designed Beneficiaries (i.e., Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries).

Thus, there are now a total of three categories of IRA (and other retirement account) beneficiaries: Non-Designated Beneficiaries, Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, and Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries.

Using these three groups, the SECURE Act’s changes to the post-death distributions rules can generally be summarized as follows:

- The old, pre-SECURE Act rules for Designated Beneficiaries apply to the newly created group of Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (i.e., they are still permitted to ‘stretch’);

- Any Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary is subject to the new 10-Year Rule; and

- There are no direct changes to the rules for Non-Designated Beneficiaries (i.e., they remain subject to the 5-Years-or-decedent’s-life-expectancy-Rule that already applied).

The Newly Created Stretch Category Of ‘Eligible Designated Beneficiaries’ Is Exempt From The SECURE Act’s 10-Year Rule

As noted earlier, the SECURE Act creates a new type of retirement account beneficiary, known as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary. While this group of individuals (and certain See-Through Trusts for their benefit) may be new, the rules that apply to them are not. Instead, Eligible Designated Beneficiaries are, in essence, shielded from the ‘evil powers’ of the SECURE Act’s termination of the ‘stretch’.

Thus, the rules that apply to the new group of Eligible Designated Beneficiaries are the same rules that applied to the old, pre-SECURE Act group of Designated beneficiaries. Eligible Designated Beneficiaries continue to be able to ‘stretch’ distributions from inherited retirement accounts, beginning in the year after death, and calculated using their Single Life Expectancy.

In short, Eligible Designated Beneficiaries get to pretend as though the SECURE Act was never passed.

Unfortunately, though, the list of Eligible Designated Beneficiaries is not very long. More specifically, an Eligible Designated Beneficiary is a Designated Beneficiary who also falls into one of the following five categories:

- The spouse of the decedent. In order to be considered an Eligible Designated Beneficiary by virtue of this provision, an individual must have been legally married to the decedent. Domestic partnerships do not count, but same-sex married would (as long as it was legal where the ceremony was performed).

Furthermore, while spouses do fall into the group of Eligible Designated Beneficiaries and can stretch distributions, the SECURE Act did not directly impact other potential post-death retirement account rules that also apply favorably (and only) to spouses.

Spouses can, for instance, still roll over a deceased spouse’s inherited retirement account into their own retirement account as well (unimpacted by the SECURE Act). And in the event that a spouse chooses to remain a beneficiary by establishing (and maintaining) an inherited IRA (or other inherited retirement account), they will not have to take RMDs until the year that the deceased spouse would have reached age 72 (formerly 70 ½, prior to the SECURE Act’s change to the age at which RMDs begin).

- A disabled individual. An individual is considered “disabled” if they meet the rules outlined by IRC Section 72(m)(7). This is a fairly restrictive definition of disability, which states:

…an individual shall be considered to be disabled if he is unable to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or to be of long-continued and indefinite duration.

Thus, individuals who are only partially disabled, or whose disability prevents them from engaging in previous employment but would allow them to engage in other substantially gainful activity, would generally not qualify.

- Chronically ill persons – An individual will generally be considered “chronically ill” if they meet the rules outlined by IRC Section 7702B(c)(2). However, instead of IRC Section 7702B(c)(2)(A)(i)’s requirement that an individual be unable to perform at least two of the six activities of daily living (ADLs) for a period of ‘only’ 90 days, the SECURE Act requires that, for purposes of being considered an Eligible Designated Beneficiary, such an impairment be considered “an indefinite one which is reasonably expected to be lengthy in nature”.

The six activities of daily living are defined as:

- Eating;

- Toileting;

- Transferring;

- Bathing;

- Dressing; and

- Continence

- Individuals who are not more than 10 years younger than the decedent –Anyone who is not more than 10 years younger than the decedent can continue to stretch distributions without regard to the SECURE Act’s new 10-Year Rule. Beneficiaries who may be most likely to benefit from this provision include parents, siblings, and unmarried partners of the decedent (provided that they are not more than 10 years younger).

However, while this seems pretty straightforward, one issue which IRS will hopefully address via future guidance, is how the phrase “not more than 10 years younger” should be interpreted: Are the 10 years exactly 10 years? Or is it more than 10 calendar years?

Suppose, for instance, that an IRA owner born on March 1, 1970, passes away in 2020 (and thus, the changes to the post-death distribution rules made by the SECURE Act are applicable). Further suppose that the sole beneficiary of the account is the decedent’s cousin, who was born on December 1, 1980.

A plain (literal) reading of new IRC Section 401(a)(9)(E)(v) would lead one to believe that such a beneficiary would be subject to the new 10-Year Rule and would not be eligible for the ‘stretch’, because they are exactly 10 years and 9 months younger than the decedent.

Alternatively, it would be entirely reasonable for the IRS to interpret the Congressional intent of the provision to mean “not more than 10 calendar years younger”, since such an interpretation would be consistent with other required minimum distribution rules (which are typically calendar-year based and not tied to the exact mid-year anniversary date or milestone). For example, the Joint Life and Last Survivor Expectancy Table is used by retirement accounts owners whose sole beneficiary is a spouse more than 10 calendar years younger.

With any luck, the IRS will clarify its position on this matter, one way or another, via regulations or other guidance.

- Minor children of the decedent - Of all different types of Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, the most complex group may be minor children of the decedent. And for several reasons.

First, it is critical to emphasize that this group consists not of minor children, in general, but rather solely the minor children of the deceased retirement account owner. Thus, for instance, minor grandchildren of a decedent would not be part of this group still eligible to stretch, and would generally be subject to the 10-Year Rule.

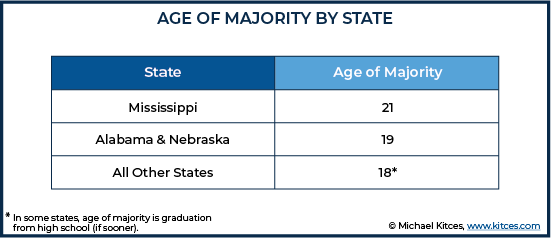

Additionally, unlike the four previous types of Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, who have permanent (until they die) status as Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, minor children of the deceased retirement account owner only enjoy that beneficiary status until they reach the age of majority. Upon reaching such age, the child ‘flips’ from being an Eligible Designated Beneficiary (stretching based on their life expectancy) to being a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary, triggering the beginning of the application of the 10-Year Rule (which will generally force 10-year liquidation generally by age 28, for states where the applicable age of majority was 18 begin with).

Example #1: Thelma is a 40-year-old single mother with a 12-year-old daughter, Louise, who is the beneficiary of her IRA. Unfortunately, Thelma dies an early death, and Louise inherits her IRA in the year of her 12th birthday. As a result, Louise must generally begin taking ‘stretch’ RMDs beginning the following year, in the year she turns 13.

Suppose, now, that Louise lives in a state with an age of majority of 18 and does not go to college (more on this in a moment). As a result, she will take stretch distributions from 13 until she reaches the age of majority at 18. At that time, the 10-Year Rule will take effect, requiring any remaining funds in the inherited IRA to be distributed over the ensuing decade.

Minor Children Who Are Eligible Designated Beneficiaries Become Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries Upon Reaching The Age of Majority

The SECURE Act’s temporary relief for minor beneficiaries of the deceased account holder raises one very obvious question… “Until what age is someone considered a minor?”

In general, the determination of who is (and subsequently, who is not) a minor is a matter of state law. Most states deem an individual to have reached the age of majority upon turning 18, while Alabama and Nebraska sets the age of majority at 19, and Mississippi considers an individual a minor until they reach the age of 21.

(Nerd Note: The age of majority, and the age at which an individual is entitled to assets held within an UTMA account, are not necessarily the same age. In fact, in most states, the age of majority is reached prior to the age at which control over assets in an UTMA account may/must be turned over to the beneficiary.)

Given the fact that Mississippi, at age 21, is the state with the oldest age of majority, it would be reasonable to assume that if a minor child were to inherit an IRA or other retirement account, that by age 31 (the latest age of majority of 21 plus the 10-Year Rule) such an account would have to be emptied. A little-known Treasury Regulation, however, may hold the key to a few more years of tax deferral for particularly studious children.

More specifically, Treasury Regulation Section 1.401(a)(9)-6, Q&A–15 states, in part:

Q-15: Are there special rules applicable to payments made under a defined benefit plan or annuity contract to a surviving child?

A-15: Yes, pursuant to section 401(a)(9)(F), payments under a defined benefit plan or annuity contract that are made to an employee's child until such child reaches the age of majority (or dies, if earlier) may be treated, for purposes of section 401(a)(9), as if such payments were made to the surviving spouse to the extent they become payable to the surviving spouse upon cessation of the payments to the child. For purposes of the preceding sentence, a child may be treated as having not reached the age of majority if the child has not completed a specified course of education and is under the age of 26. [emphasis added]

While this Treasury Regulation was originally crafted to address payments to minors under a defined benefit plan or annuity contract, it appears it will now apply to inherited IRAs and other defined contribution plans left to minor children of the deceased IRA owner as well. Thus, a minor child who is continuing a “specified course of education” should be able to continue ‘stretching’ distributions using the old, pre-SECURE Act life expectancy method until they reach the age of 26 – regardless of the age of majority applicable in their state – at which point, the 10-Year Rule would begin to apply.

What, exactly, is a specified course of education? Well, that’s unfortunately an area where there just isn’t a lot of guidance. Given the heightened importance of the rule going forward, perhaps the IRS will decide to provide some additional guidance. But absent such guidance, or until such guidance is released, whether a child meets the definition of “not completed a specified course of education” will remain a highly subjective matter, subject to interpretation.

Clearly, a child currently enrolled full-time in college or in post-graduate courses would have no problem meeting this requirement. But what about a child who is working part-time and taking classes part-time? Does the “specified course of education” have to be at a formal institution of higher learning, or would progress towards a vocational degree or in an apprenticeship program count? Unfortunately, there is no clear answer.

The New 10-Year Rule For Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries

The single biggest impact of the changes made to the post-death distribution rules made by the SECURE Act will be felt by Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, who do not qualify for the list of Eligible Designated Beneficiaries and thus will not be permitted to stretch anymore (unlike their Eligible Designated Beneficiary brethren). Which, notably, may change not only the rules for Designated Beneficiaries who are in the “Non-Eligible” status, but also certain trusts as well.

As while Designated Beneficiaries, in general, must be a living, breathing human being, some trusts could also qualify to be treated as Designated Beneficiaries, provided that they meet certain rules outlined by the IRS in Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-4, Q&A-5. Such trusts, known as See-Through Trusts, must be:

- Valid under state law;

- Irrevocable upon the retirement account owner’s death;

- Contain identifiable beneficiaries; and

- Submitted to the IRA custodian or plan administrator by October 31st following the year of death (or in the alternate, a certified list of trust beneficiaries can be provided by the same date).

Instead of being able to ‘stretch’ inherited retirement account distributions over the lifetime of an Eligible Designated Beneficiary, the SECURE Act subjects Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries to a new 10-Year Rule. This 10-Year Rule requires that such beneficiaries distribute the balance of an inherited account by the end of the 10th year after the year of death. So, for instance, a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary who inherits an IRA during 2020 would have 10 years to distribute the balance of their inherited account beginning on January 1, 2021 (the year after the year of death) and ending on December 31, 2030.

Notably, with the exception of the final year, there are no requirements for distributions to be taken within the 10-year period. Thus, a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary could choose to take distributions ratably throughout the 10-year period in an effort to spread out the income from the inherited account as evenly as possible.

Conversely, a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary could choose to avoid taking any distributions during the first nine years after death and, instead, take one giant distribution in the final 10th year following death. And of course, there are literally millions of distribution combinations in between.

Can Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries Still Use The “As Rapidly” Rule?

One question for which the answer isn’t quite clear from the SECURE Act’s language is whether a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary can continue to use what’s commonly known as the “As Rapidly” Rule.

In short, prior to the SECURE Act, if death occurred on or after the retirement account owner’s Required Beginning Date (RBD), a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary was able to take distributions from the inherited account using their own life expectancy or, if the original owner’s was longer, using the owner’s life expectancy instead.

In other words, the beneficiary just had to distribute the funds at least “As Rapidly” as the owner would have been required. (This is in contrast to the account owner’s death occurring before the RBD, in which case the Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary must generally base distributions using only their own life expectancy.)

The SECURE Act makes no changes to the As Rapidly Rule found under IRC Section 401(a)(9)(B)(i)(II). However, it does say that Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries get the 10-Year Rule… without saying something like, “They get the 10-Year Rule or can opt to use the As Rapidly Rule” (or not).

Nevertheless, the As Rapidly Rule is still what applies to Non-Designated Beneficiaries, such as trusts or charities, who inherit a retirement account from a decedent dying on or after their RBD. It’s hard to imagine a scenario where Congress would have intended to place Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries at a disadvantage relative to Non-Designated Beneficiaries and, as such, most experts believe that Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries should still be able to opt into the As Rapidly Rule.

Using the As Rapidly Rule, there would be a short window of time from the decedent’s age 73 to 78, where distributions could be extended beyond the 10 years required under the 10-Year Rule. For instance, if death occurred at 73, for which the Single Lifetime Table factor is 14.8, then under the As Rapidly Rule, distributions to a beneficiary would begin the following year using a factor of 14.8 – 1 =13.8.

Thus, for such a beneficiary, the As Rapidly Rule would actually extend the 10-Year Rule by up to four years. However, unlike the 10-Year Rule, which provides ultimate flexibility within the 10 years (i.e., permitting all distributions to be delayed until the 10th year), the “As Rapidly” rule would require annual distributions, which may (or may not) reduce or eliminate any net benefit of the approach (as waiting until the 10th year for all distributions may often still be better than stretching for up to 14 years but being required to take out approximately 10/14ths of the distributions already by the 10th year!).

The SECURE Act Makes No Direct Changes To The Rules For Non-Designated Beneficiaries And Their 5-Year Rule

As noted earlier, the SECURE Act makes no direct changes to the post-death distribution rules for Non-Designated Beneficiaries, such as charities, estates, and non-See-Through Trusts.

Which means that such beneficiaries must continue to distribute all the funds from an inherited retirement account by the end of the fifth year after the year of death (the “5-Year Rule”) if the IRA or plan participant died prior to their Required Beginning Date (RBD). Similarly, distributions of inherited funds must be made over the remaining life expectancy of the decedent if death occurred on or after the RBD.

While these rules remain exactly the same as prior to the SECURE Act’s effective date, though, the SECURE Act does have an indirect impact on their applicability. Notably, the SECURE Act changes the RBD for those reaching age 70 ½ in 2020 or later. For such IRA owners and (most) plan participants (except when an exception, such as the Still-Working Exception applies) the RBD is now April 1st of the year following the year they reach age 72, instead of the old, pre-SECURE Act date of April 1st following the year that they reached 70 ½.

Thus, in light of the SECURE Act’s change to the RBD, more people will presumably die prior to their RBD than in the past. Accordingly, more Non-Designated Beneficiaries will be stuck with the 5-Year Rule (which applies when death occurs prior to that RBD date).

Delayed Applicability Of The SECURE Act’s Changes For Collective Bargaining Agreement, TSP, And Other Government Plans

For the majority of retirement account owners, the full brunt of the SECURE Act’s changes to the post-death distribution rules for beneficiaries was effective beginning January 1, 2020. But while that may be the case for most retirement account owners, it’s not the case for all retirement account owners.

Notably, there are three exceptions to the SECURE Act’s ‘death’ of the ‘stretch’ for Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries as of January 1, 2020. Those exceptions are:

- Annuities in which, prior to January 1, 2020, an individual irrevocably annuitized amounts over a life or joint-life expectancy, or in which an individual elected an irrevocable income option that will begin at a later point, are exempt entirely (and follow the contractual provisions of the annuity contract).

- Plans maintained with an effective date pursuant to a collective bargaining agreement of January 1, 2022 (unless the collectively bargained agreement terminates sooner).

- The effective date for governmental plans, such as 403(b) and 457(b) plans sponsored by state and local governments, and the Thrift Savings Plan sponsored by the Federal government (and in which Congresspersons, themselves, participate).

The SECURE Act is considered by many to be the most important piece of retirement legislation in the past 15 years, and the most significant provision of that legislation, for many, is its changes to the post-death distribution rules for Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries of inherited retirement accounts. While the ‘stretch’ IRA has long been an incredibly effective tool in the planner’s arsenal, it is no longer applicable for most non-spouse beneficiaries.

Notably, the post-SECURE Act regime creates three groups of beneficiaries from the pre-SECURE Act’s two groups of beneficiaries. The treatment for Non-Designated Beneficiaries largely stays the same, with death prior to a retirement account owner’s RBD triggering the 5-Year Rule, and death after the RBD continuing to require distributions over the deceased owner’s remaining life expectancy.

Similarly, for the select group of Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, life after the SECURE Act largely continues on as if the law had not been enacted, as the ‘stretch’, for them, is preserved. But for Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries the new 10-Year Rule changes the game by eliminating one of the most beneficial provisions in the entire Tax Code, the ‘stretch’