Executive Summary

Despite the recent Nobel Prize given to its originator, the Shiller cyclically-adjusted P/E (or "CAPE") ratio continues to be controversial, driven in no small part by its current "reading" that markets are overvalued, yet they continue to climb higher and higher... a formula that has played out in the recent past as well, in both the mid-2000s and especially the late 1990s. Yet the poor recent predictive performance of Shiller CAPE shouldn't entirely be a surprise; it has never had a particularly high correlation to year-over-year market returns.

Nonetheless, the reality is that while Shiller CAPE has little predictive value in the short term, its correlation to market returns is far stronger over longer time periods; Shiller CAPE shows its strongest correlation to nominal returns over an 8-year time horizon, and is actually most predictive of real returns over an *18* year time horizon... supporting Benjamin Graham's old adage that the markets may be a voting machine in the short run, but they are ultimately a weighing machine in the long run as valuation eventually takes hold. On the other hand, over very long time horizons (e.g., 30 years) Shiller CAPE once again begins to lose its value as other longer-term structural market factors take hold.

The fact that Shiller CAPE is a strong predictor of market performance in the long run (but not the "ultra" long run, nor the short run) suggests that the valuation measure does have use, but only if applied in the correct contexts. For instance, while all this suggests that Shiller CAPE may be a poor market-timing investment indicator, clients who are retiring and exposed to "sequence-of-returns" risk over the first half of their retirement may benefit greatly by adjusting their initial spending levels in light of market valuation at the start of retirement. Similarly, those considering the benefits of delaying Social Security - or choosing to annuitize or claim pension payments over an equivalent lump sum - would do well to evaluate their decision in light of whether there is a market-valuation-based headwind or tailwind underway. Thus, even if Shiller CAPE is a poor market-timing indicator, that doesn't mean it's useless at all when it comes to retirement planning!

Short-Term Predictive Value of CAPE

Shiller CAPE - a "Cyclically-Adjusted" P/E ratio based on the current price of the market and a 10-year inflation-adjusted average of trailing earnings - has both gained in popularity and notoriety in recent years, and especially since its originator Professor Robert Shiller was a (joint) winner for last year's Nobel Prize in Economics. Shiller's Nobel Prize implicitly and explicitly acknowledged his valuation work and some of its predictive value; yet at the same time, after nearly two decades of elevated earnings and P/E ratios, punctuated by two significant bear markets (2000-2002 and 2008-2009) but also three astonishing bull markets (the late 1990s, 2003-2007, and 2009-present), many are questioning whether Shiller CAPE is really all that predictive or not at this point.

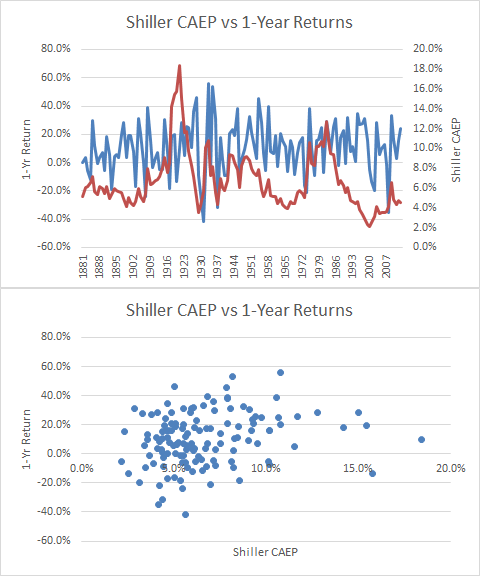

A look at the relationship between the Shiller P/E ratio - or its inverse, the Cyclically-Adjusted E/P (or CAEP) ratio - and 1-year stock market returns suggests that the critics are right about the value of CAPE, at least in the short run. There is almost no evident relationship between the E/P ratio of the market and its return over the subsequent year. The correlation of the charts below (Shiller CAEP in red, returns in blue) is a meager 0.23.

On the other hand, few advocates for long-term value investing would make the case that valuation is an especially effective predictor of short-term market performance. Deep value investors are long known for buying and holding unloved stocks for an extended period of time. In fact, it was the father of value investing himself, Benjamin Graham, who is noted for saying that the markets are like a voting machine in the short-run, and only in the long run are they a weighing machine that actually takes into account the true economic substance of a company. Which suggests that perhaps Shiller CAPE, too, deserves to be evaluated based on its performance in the long run, not the short run.

Long-Term Predictive Value of Shiller CAPE And CAEP

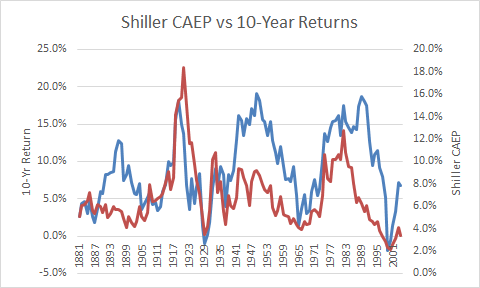

As Graham's statement would suggest, the predictive value of Shiller CAEP does in fact improve over longer time periods. For instance, the chart below graphs the Shiller CAEP (red line) and the subsequent (nominal) annualized return of the markets over the next 10 years (blue line). Although there are still some significant gaps, over this time horizon the correlation more than doubles to 0.53 (compared to the 1-yr return correlation). (Note: Given the ratio is E/P instead of P/E, a high E/P indicates the market is favorably valued and should align with higher returns, and vice versa.)

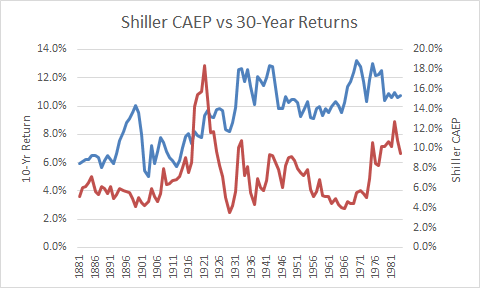

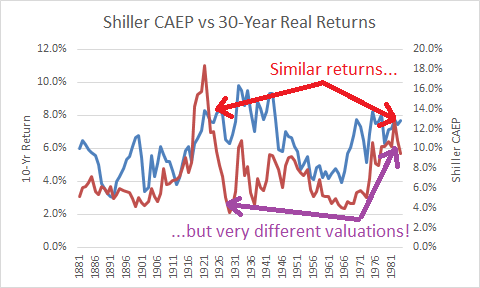

On the other hand, while the predictive value of CAEP improves over longer time periods, the reality is that there is such thing as being "too long term" to use Shiller CAEP to predict returns. Accordingly, the chart below graphs Shiller CAEP vs 30-year returns, where the predictive value is actually even worse than on a 1-year basis (a correlation of only 0.19).

Of course, over time horizons this long, inflation is also a significant factor that can distort returns; in fact, Shiller acknowledged the impact of inflation in calculating the CAPE ratio in the first place (as the trailing 10-year earnings are adjusted for inflation). When the Shiller CAEP is measured against 30-year real returns, the predictive value improves notably - the correlation rises to 0.50. However, significant deviations are present, even at extremes; note that, as the Philosophical Economics blog also recently pointed out, the 30-year real return is almost exactly the same in 1929 and 1981 (indicated with red arrows), despite the fact that the Shiller CAEP was at opposite extremes during these time periods (marked with purple arrows)!

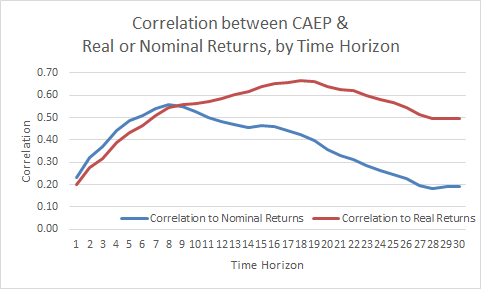

To explore the variability of the predictive value of Shiller CAEP, the chart below graphs the correlation between CAEP and nominal or real returns over varying time horizons. As the chart reveals, CAEP is most predictive of nominal returns over an intermediate term time horizon (peaking out over an 8-year time horizon). Over a similar (or shorter) time horizon, CAEP is actually less predictive of real returns, although over longer time horizons CAEP actually becomes more predictive, ultimately peaking out with the maximal correlation and predictive value over an 18-year time horizon!

Relevance Of Shiller CAPE For Financial Planning Decisions

Given the "goldilocks" predictive value of Shiller CAPE ratios - it doesn't work over time periods that are too short, nor those that are too long, but just the ones right in the middle - the results suggest it's especially important to make the predictive time horizon of market valuation to planning decisions that have relevance over that time period.

Accordingly, the results suggest that using Shiller P/E valuations as a "market timing" indicator will fare quite poorly; there is very little relationship at all between market valuation and short-term market results, as evidenced by both the historical data, and the experience of any investor over the past two decades and the astonishing breadth of bull and bear markets that have occurred over the time period. On the other hand, while P/E ratios appear to have far more predictive value over longer time periods - especially 10-20 year real returns - the sad reality is that most investors simply do not give their advisors time horizons that long before judging them for results. In other words, from a practical perspective it may not matter if market valuation is right "in the long run" if you're at risk of being fired for short-term relative underperformance in the meantime (e.g., for getting conservative in overvalued markets and then being forced to wait years before the markets "prove you right" as would have occurred for the conservative investor in the mid-2000s or especially the late 1990s).

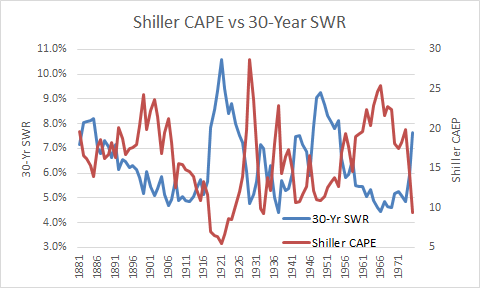

Nonetheless, this doesn't mean that Shiller CAPE has no relevance for financial planning decisions. For instance, prior research from the May 2008 issue of "The Kitces Report" has shown that Shiller CAPE ratios have an astonishingly strong -0.74 correlation to safe withdrawal rates and can help predict a reasonable starting point for retirement spending; because the long-term sustainability of retirement spending is most sensitive to an unfavorable sequence of returns in the first half of retirement, Shiller CAPE's predictive value aligns quite well and helps to provide valuable insight about whether the prospective retiree faces an important headwind or tailwind in the early years of retirement. Notably, the results indicate Shiller CAPE is more correlated to safe withdrawal rates than it is to market returns themselves!

Information about long-term returns, and whether the investor likely faces a valuation-based headwind or tailwind, can also have implications for the discount/growth rates used to evaluate other strategies as well. For instance, the relative value of delaying Social Security is impacted by the assumption regarding real returns for the available portfolio (as there's less value to delaying if you could earn more with your money by taking benefits earlier, and conversely there's more value to delaying if the opportunity cost of your investment portfolio was limited anyway). Similarly, this would imply that the implicit market-hedging value of delaying Social Security is more relevant when Shiller CAPE is high (and there is a greater risk of substandard returns) than when it is low. More generally, higher or lower expected returns - as adjusted for market valuation - would have implications for the relative value of any lump-sum-versus-annuity decisions (whether considering the outright purchase of an immediate annuity, or evaluating a pension-versus-lump-sum scenario).

The bottom line, though, is simply this: while the data does suggest that market valuation tools like Shiller CAPE are a poor predictor of short-term market performance, and may be very limited as a market timing tool to improve performance, the longer-term predictive value of Shiller CAPE and its CAEP inverse suggest that it is still relevant for planning decisions where the focal point truly is on long-term returns, from setting an appropriate safe withdrawal rate (or possibly even an optimal asset allocation glidepath) to evaluating the opportunity cost of funds for lifetime income strategies like delaying Social Security, purchasing an annuity, or considering a pension lump sum!

In point of fact, perhaps this distinction between valuation's long-run-but-not-short-run predictive value was the very reason the Nobel Prize committee gave its award jointly to Shiller for his work on how stock returns can be predicted in the long run, while simultaneously giving it to Eugene Fama for his efficient markets research showing that stock returns cannot be effectively predicted in the short run!

What do you think? Do you find Shiller CAPE ratios to be relevant in your practice? Do you use it as an investment tool? Do you use it in other contexts like determining sustainable retirement spending or the value of delaying Social Security?