Executive Summary

While being a tax-paying citizen of the United States does provide for certain benefits and protections, and several organizations are responsible for helping to oversee and ensure that tax dollars are used in a reasonably productive manner, most people don’t think of their tax dollars as something that provides a specific and tangible “return on investment”. Yet the irony is that when it comes to FICA taxes on wages or self-employment income, which are used to fund Social Security and Medicare benefits, it actually is possible to have FICA taxes produce a long-term Return On Investment (ROI).

The reason that Social Security FICA taxes can generate a positive ROI is that ultimately, any wages or self-employment income that is taxed for Social Security purposes is also income that will be considered when calculating Social Security benefits. And since Social Security itself is functionally an income-replacement formula – based on an individual’s highest 35 years of inflation-adjusted earnings, with means-tested replacement rates based on their income levels – the more income that is included for FICA tax purposes, the higher Social Security benefits will be.

In fact, those eligible for the lower and middle FICA replacement rates – up to $64,788 of lifetime inflation-adjusted average earnings – the ROI of paying FICA taxes can generate real returns that are actually competitive with current TIPS bond yields, potentially rising even higher for those in the lowest income tier, especially for individuals who are also older (in their 50s or early 60s) but very healthy (with a long life expectancy to continue receiving Social Security benefits in retirement itself). Although for upper-income individuals, even though with above-average health, the ROI on Social Security FICA taxes is generally negative.

The significance of the potential for Social Security taxes generating a positive ROI is that, at a minimum, paying FICA taxes for many is less of a “tax” and more of a forced-savings investment with a bond-like return (albeit not available as a liquid account balance and only as a lifetime Social Security annuity payment). And for those in more flexible situations to control their income reported as wages – from S corporation owners, to those with spouses or other family members who might be paid through the family business – the potential for a positive ROI from FICA taxes can substantially alter intra-family business tax planning strategies!

How Paying FICA Taxes Impacts Social Security Benefits

In a similar manner to a classic pension, Social Security benefits are calculated based on an income replacement formula.

However, while the typical pension might accrue the replacement rate based on years of service – e.g., 2% of income replacement per year of service, up to a 70% replacement rate after 35 years – Social Security benefit replacement rates are means-tested based on the worker’s income. Consequently, replacement rates vary from 90% for the first $10,752/year of income, down to 32% for the next $54,036/year of income (up to a total of $64,788 of annual income), falling all the way to a 15% replacement rate for any income above that $64,788 threshold (up to the maximum Social Security wage base of $128,400/year).

In addition, while pensions often apply their income replacement rate to the final year’s salary, or perhaps a final 3- or 5-year earnings average, Social Security applies the replacement rate to the individual’s highest 35-year (inflation-adjusted) earnings years. As long as Social Security (i.e., FICA) taxes were paid on the income, then that income is included in the historical earnings formula. Thus, the maximum income to be subject to Social Security taxes in 2018 – which is $128,400 (after being corrected from $128,700) – is also the maximum income to be considered (and is annually adjusted for inflation) when calculating historical earnings averages for Social Security benefits.

Over time, as a worker continues to work and earn income (and pays FICA taxes on that income), the income adds to the highest-35-year earnings average, and can boost prospective Social Security benefits in the future. After all, by default, a new worker starts out with 35 “zeros” for their 35-year average – because they have no earnings yet – and each year of new income effectively replaces a $0 amount and increases the 35-year average by 1/35th of the annual earnings amount. Which effectively means that 2.86% (which is 1/35th) of each year’s income is added to Social Security benefits at a 90%, 32%, or 15% replacement rate, or each year’s income itself increases Social Security benefits by 2.57%, 0.91%, or 0.43% of that amount of earned income, respectively. (These are sometimes called Social Security “bend points”, because the replacement rates change and “bend” as each income threshold is reached.)

Example 1. Charlie will earn $60,000 from his job this year. He does not yet have 35 years of working history. As a result, Charlie’s lifetime earnings average will be increased by 1/35th (approximately 2.86%) of $60,000, or about $1,714. If Charlie is in the 90% replacement tier based on his total lifetime average earnings, his Social Security benefits in retirement will be increased by $1,543/year (which is 2.57% of his earnings). However, if he’s only in the 32% replacement tier, his $60,000 of earnings will only increase benefits by $548/year (or 0.91% of his income). And if he’s in the 15% replacement tier, his earnings will only boost his Social Security retirement benefit by $257/year (which is 0.43% of his earned income).

Of course, the reality is that Social Security benefits do have a cost as well – in the form of the FICA taxes that must be paid on that income, in order to have the income from continuing to work counted towards the calculation of future Social Security benefits. The standard FICA tax rate is 12.4% (paid as 6.2% by the employee and 6.2% via employer payroll taxes, or the whole 12.4% at once for self-employed individuals), plus 2.9% for Medicare taxes (which aren’t part of the Social Security tax rules and formula, but any income taxed for Social Security purposes will include the Medicare component as well). Which means in essence, having income included for future Social Security benefits increases future benefits by 0.43% to 2.57% of that income, but has a “cost” of 12.4% + 2.9% = 15.3% of the income today.

Example 1b. Continuing the earlier example, in order to receive credit for his $60,000 of earnings this year, Charlie must pay 15.3% of FICA taxes, or $9,180, in order to earn his extra benefits that will be between 0.43% and 2.57% (or $257/year up to $1,543/year) of his income.

Assuming that Charlie is 55 years old, his average inflation-adjusted lifetime earnings is about $50,000, and he doesn’t yet have 35 years of earnings history, this $60,000 of income that results in $9,180 in taxes will increase his future benefits by $548/year (as he would be in the 32% replacement tier). Which means his $9,180 of taxes today would produce an extra $548/year of income potential in 11 years, at his full retirement age of 66. If Charlie has an age-85 life expectancy, he would be expected to receive 20 years of cumulative payments (from the start of his 66th year to the end of his 85th), which is the equivalent of a real inflation-adjusted return of about 0.9%/year (or a total return equivalent of 3.9%/year assuming a 3% cost-of-living adjustment on the Social Security payments).

The ROI Of Paying FICA Taxes

While the prospective “return” on paying FICA taxes – in the form of higher Social Security benefits – may not be an extraordinarily high return, it is notable that the 0.9%/year real return in the preceding example is approximately equivalent to current 30-year real TIPS yields in today’s environment anyway. Which means, ironically, “paying FICA taxes” is actually functioning less as a tax, and more as the equivalent of a (forced) TIPS bond investment! Albeit a form of TIPS bond investment where the final cumulative yield is heavily dependent on how many years the individual actually stays alive to receive those payments (as is the case for any lump-sum-now-in-exchange-for-lifetime-annuity payments structure).

In practice, the prospective Return On Investment (ROI) of paying FICA taxes will vary, and is contingent on three core factors, all of which impact the internal rate of return of future Social Security benefits to be received:

- Life Expectancy. Because FICA taxes are fixed up front (at 15.3% of income), but Social Security benefits are simply paid “for life”, how long an individual actually lives to receive those future Social Security payments has a dramatic impact on the cumulative ROI of paying FICA taxes. Simply put, the longer an individual’s life expectancy, the better the value of paying FICA taxes – as the individual receives more years of payments for the same upfront (tax) cost. Conversely, for those in poor health, FICA taxes are generally a losing value proposition, as there may not even be enough future benefits payments to make back the upfront tax payment (with the caveat that they may still be valuable in the form of Survivor benefits to a surviving spouse, even if the worker themselves doesn’t live longer to get many or any payments).

- Time Horizon. Social Security benefits aren’t payable until Full Retirement Age (which is age 66 and 4 months for those turning 62 in 2018). However, FICA taxes are due when the income is earned. For instance, in the earlier example, Charlie would have received the same $548/month of payments beginning at full retirement age for the 15.3% FICA taxes he paid today… regardless of whether he was age 55, or 45, or 35. However, paying $9,180 in taxes (on $60,000 of income) at age 35 (instead of age 55) means waiting 31 years (instead of just 11 years) for benefits, and a longer waiting period for the same future payment reduces the prospective ROI of FICA taxes (all else being equal).

- Income Replacement Tier (Social Security Bend Points). The Social Security replacement rates are calculated based on an individual’s historical inflation-adjusted earnings, applying progressively lower replacement rates to higher levels of lifetime earnings. As a result, just as it’s important to know what marginal tax bracket someone is in to calculate the marginal benefits of a tax strategy, it’s crucial to know which marginal income replacement tier someone is in for calculating their Social Security benefits. Notably, this calculation is based on the individual’s lifetime inflation-adjusted earnings history, which means adjusting an individual’s historical earnings record (e.g., on their Social Security statement) by the current wage indexing factors from the Social Security Administration to determine which marginal replacement rate tier the individual is really in. It’s not enough to simply calculate average historical earnings from Social Security statement itself, as earnings from the more distant past will be lower simply because compounding inflation over the years had not yet increased them to more recent levels (thus understating lifetime average earnings in today’s dollars, which is how they’re calculated for Social Security benefits purposes).

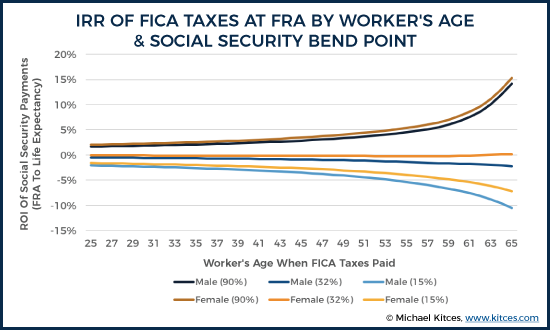

Accordingly, the chart below shows the prospective internal rate of return on paying FICA taxes, based on these three factors, assuming standard life expectancy from full retirement age (for males and females separately), at the varying income replacement tiers, and at various time horizons (based on the individual’s age when the income is earned and FICA taxes are paid).

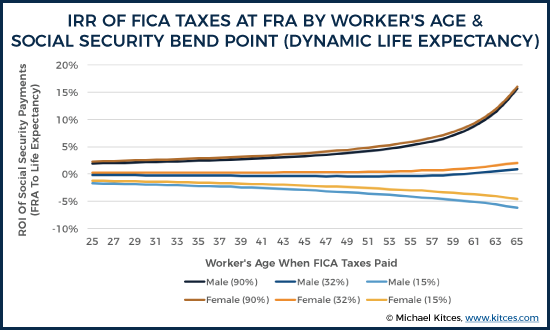

Notably, the dynamic of time horizon and life expectancy is a bit more nuanced, as the reality is that life expectancy itself changes as people age – according to Social Security tables, life expectancy from birth is about 79 for a male and 82 for a female, but for those who have already reached age 65, life expectancy is about 84 for a male and 87 for a female.

More generally, this means that at younger ages, not only is the time horizon until Social Security benefits longer, but prospective life expectancy time horizon is slightly shorter as well. Accordingly, the chart below shows the prospective internal rates of return, but based on the prospective life expectancies of males and females at the age they’d be evaluating the earnings impact.

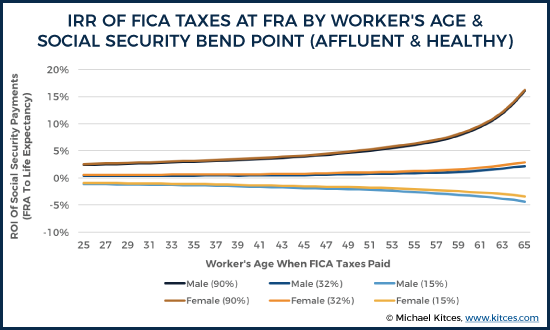

Of course, it’s also important to note that those with above-average incomes – who tend to be the clients of financial advisors – also tend to have above-average life expectancies. Accordingly, the chart below shows the prospective internal rate of return on FICA taxes, assuming the life expectancy for healthy affluent individuals from the Society of Actuaries "White Collar" mortality tables.

Paying FICA Taxes Beyond 35 Years Of Earnings History

As discussed earlier, for those who don’t even have 35 years of historical earnings, each new year of income that is FICA-taxed increases the historical average by 1/35th of that amount, to which the 90%, 32%, or 15% replacement rates are then applied.

However, for those who already have 35 years of earnings history, continuing to work and adding a new year of income only increases benefits to the extent the new income replaces one of the existing 35 years of earnings (with a new higher amount). And in such cases, benefits will still only be increased based on the income differential (between the old and new amounts), not the full amount of new earnings.

Example 2. Continuing the earlier example, assume that Charlie not only had a lifetime average earnings of about $50,000, but he also already had a full 35 years of historical earnings, and his lowest (inflation-adjusted) earnings year was $25,000 of income. As a result, earning $60,000 this year would increase his Social Security benefits, but based not on the entire $60,000, just the $35,000 difference from swapping out a prior $25,000 income year for a new $60,000 income year.

Thus, Charlie’s future Social Security benefits would only increase by 1/35th of the income differential of $60,000 - $25,000 = $35,000 / 35 = $1,000, which at a 32% replacement tier would increase his benefits at full retirement age by just $320/year (instead of the original $548/year), albeit for the same FICA tax obligation of $9,180 (as FICA taxes are always paid on all of the income, not just the incremental amount!).

Ultimately, this means the upside of FICA taxes will be more limited any time new earnings are replacing prior earnings (rather than just replacing a “$0” for someone who doesn’t yet have 35 years of earnings history), given that it is only the income differential (rather than the entire income amount) that will contribute towards Social Security benefits.

And in the logical extreme, individuals whose later years of earnings are lower than any of their prior highest-35-years (after adjusting for inflation) will receive no additional Social Security benefits for their additional FICA taxes paid. Which is important, as recent research on real earnings growth for workers suggests that the bulk of real wage increases come in the early years, and that real wage growth is often negative in a worker’s final decade (after age 55).

Maximizing The ROI Of FICA Taxes For Higher Social Security Benefits

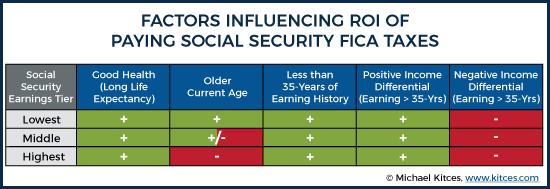

In the end, the impact of paying FICA taxes – and potentially receiving higher Social Security benefits in the future – will vary substantially from one individual to the next, depending on the factors of time horizon, life expectancy, Social Security replacement tier, as well as the prospective earnings differential between current income and the lowest of the historical highest-35-years of earnings (particularly in situations where the prior income year being replaced is not a “$0” for someone who didn’t have 35 years of earnings yet).

Nonetheless, given the results shown earlier, some useful planning generalizations can be made.

Overall, paying FICA taxes on income in exchange for Social Security benefits will work best for those who are older (shorter time horizon to when benefits begin), who are healthy (good life expectancy), and who are in the lower and middle earnings tiers… particularly if they do not already have 35 years of FICA-taxed earnings.

By contrast, those who are in the top Social Security replacement tier (a 35-year historical inflation-adjusted earnings average that exceeds $64,788/year) may see a negative ROI for FICA taxes, as will those who have poor life expectancy (and may not live to see many or any payments), and also those for whom the income differential is small (e.g., paying FICA taxes on $60,000 but having only $10,000 of the income “count” because it is replacing a $50,000 prior earnings year). In the extreme, individuals should be especially wary of paying unnecessary FICA taxes in situations where their current earnings are lower than any of their highest 35-year historical earnings years, as the marginal increase in Social Security benefits will be $0 (even though the tax bill is based on the same 15.3% rate!).

Of course, the reality is that most people don’t really have a “choice” about paying FICA taxes anyway. To the extent that income is earned and reported as such, FICA taxes must be paid, and Social Security benefits will simply accrue (to the extent they do).

Nonetheless, understanding the prospective ROI of FICA taxes is important, from many perspectives. First and foremost, for some – especially those in the lowest income replacement tier – the prospective ROI of FICA taxes actually represents a substantial additional incentive to work. As even though they’re “taxes” being paid, the individual actually receives a positive net return on their tax dollars, making the payment of FICA taxes more akin to a form of “forced pension savings” than a tax in the classic sense. Even many in the middle-income replacement tier may see a positive ROI for FICA taxes similar to the return they’d receive by simply investing their FICA taxes into a government bond portfolio they subsequently liquidate in retirement. Especially if they have not yet accumulated 35 years of earnings history in the first place (which means they’re “replacing zeros” in their benefits calculation), and are already in their later years approaching retirement (with the shortest ROI time horizon).

On the other hand, in some cases, there is more control over choosing to pay FICA taxes to obtain the potentially favorable ROI. For instance, small business owners with an S corporation have a choice of whether to pay out business income as salary (subject to FICA taxes) or as S corp dividend distributions (not subject to FICA taxes). In such situations, it is common to minimize salary (and therefore minimize FICA taxes) and pay out as much as possible in the form of a dividend; however, choosing to pay out income as salary, below the Social Security wage base, could actually have a more beneficial outcome than avoiding the FICA taxes as a dividend distribution for those who are older, with a good life expectancy, and already falling in the lower or middle Social Security replacement tiers. (Although it will always be better to pay income above the Social Security wage base, where there is no potential Social Security benefits impact, as a dividend distribution to the extent permissible without running afoul of the “reasonable compensation” rules for S corporations.)

Similarly, in situations where the business owner controls whether to put a spouse (or even children) onto the payroll, doing so is often undesirable in situations where the primary business owner is over the Social Security wage base (where FICA taxes are “just” the 2.9% Medicare tax) but other family members are subject to the full 15.3% rate. However, if the 15.3% rate actually has a positive ROI, it may well be better to pay the income to another family member, higher FICA taxes and all.

Example 3. Jeremy earns more than $200,000/year from his small business, paying 15.3% in FICA taxes on the first $128,400 of income, and just 2.9% on the rest, for a total FICA tax liability of $21,759. His wife, Charlotte, worked outside the home for nearly 20 years earning a substantial $100,000/year salary (which was a little more than the Social Security wage base at the time), but for the past 15 years has been a stay-at-home Mom homeschooling the couple’s only child. Given that Charlotte “only” has 20 years of work history, but Social Security benefits are based on a 35-year average, her historical earnings average is “only” about $55,000/year, putting her in the 32% replacement tier, and a future Social Security benefit of more than $1,500/month.

In recent years, as their only child has gone on to public high school, though, and Charlotte has begun to do some work in Jeremy’s business. Their original plan was not to pay Charlotte, though, as reallocating $30,000 of income to her would increase their combined FICA tax liability to $25,479 (an increase of $3,720), by causing her income to be subject to 15.3% FICA taxes, while Jeremy only pays 2.9% on that last $30,000 of income.

However, given the prospective ROI of Social Security for Charlotte, in light of her age and being in the 32% replacement tier, the couple decides to go ahead and shift the $30,000 of income to Charlotte, and pay the additional $3,720 of FICA taxes (the 12.4% tax rate differential between Charlotte and Jeremy on that $30,000 of income), as they expect to more than make it back on future Social Security benefits given Charlotte’s good health!

Notably, in couples situations, it’s important to consider both the impact of additional work on Social Security benefits, and the fact that a lower earning spouse may have his/her benefit overridden by the higher earner’s spousal benefit anyway (albeit not in the example above, as even if Jeremy earns the maximum Social Security benefit of $2,788/month in 2018, Charlotte’s individual benefit starting at $1,500/month will be higher than 50% of Jeremy’s). Nonetheless, coordinating spousal benefits remains important, including and especially in situations where the couple is pursuing an ROI on FICA taxes.

The bottom line, though, is simply to recognize that paying FICA taxes isn’t always “bad”. Technically, FICA taxes are not actually “saved” to fund future Social Security benefits, but the fact that the formula for Social Security benefits is based on FICA-taxed wages (or self-employment income) means nonetheless that choosing to earn income (and have it be FICA-taxed) can actually result in a positive return on those tax dollars, at least in certain situations. Unfortunately, because Social Security benefits are implicitly means-tested – in how the Social Security bend points are determined up front – the ROI on FICA taxes generally is negative for higher-income individuals. Nonetheless, those who don’t yet have 35 years of earnings history, as well as those who fall within the bottom and middle Social Security replacement tiers, may find the prospective positive ROI of FICA taxes rather appealing. Not to mention the outright benefits of just earning more income in the first place!

So what do you think? Have you ever had any situations where you found it was beneficial to pay FICA taxes, because of the prospective increase in future Social Security benefits? In what other scenarios might it be favorable to pay FICA taxes? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!