Executive Summary

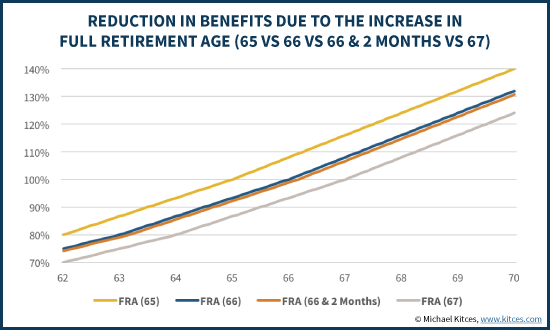

Under the original rules for Social Security, workers upon reaching their "full retirement age" of 65 became eligible for a retirement benefit, with a slight increase in benefits if the worker delayed to as late as age 70. Later, prospective retirees also got the option to start benefits as early as age 62. Thus, under the current framework, those eligible for benefits can choose any starting age between 62 and 70, with an actuarial adjustment to benefits for starting earlier or later than full retirement age.

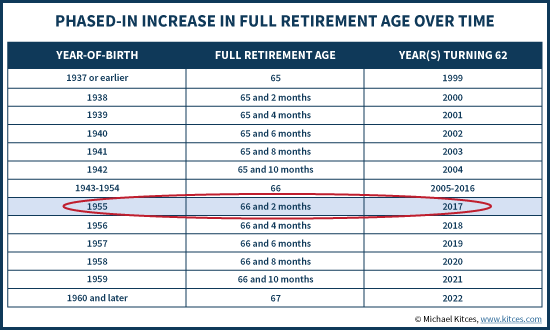

However, full retirement age itself is a moving target, as part of a multi-decade phased increase in the full retirement age from the original age 65, up to age 67 instead. For the past decade, upon reaching age 62, prospective retirees were all faced with a full retirement age of 66, but beginning in 2017, those turning age 62 this year are not actually eligible for full benefits at age 66. Instead, the full retirement age has shifted to age 66 and 2 months, and by 2022 will rise all the way to a full retirement age of 67 (for everyone born in 1960 or later). Except in the case of survivor benefits, where the full retirement age for 62-year-olds won't kick in until 2019, phasing in through 2024... which means for a period of time, there will be different full retirement ages for retirement versus survivor benefits!

Since the adjustment to full retirement age is based solely on birth year, though, the reality is that those who are impacted cannot necessarily "do" anything to change the outcome at this point – which is to effectively cause a slight decrease in the value of Social Security benefits, as the prospective retiree must wait a little longer to get the full benefit (or take a reduction to keep claiming it at the previous full retirement age of 66). Fortunately, the total reduction is barely more than a 1% haircut, growing to a maximum reduction of about 7% once the full retirement age shifts all the way to age 67.

And notably, while the full retirement age is now later – which means starting benefits at age 62 is "even earlier" and causes more of a reduction, while delaying until age 70 is "less" of a delay and doesn't give as much of an increase – the relative value of delaying Social Security benefits isn't substantively changed. For those who are optimistic about life expectancy, concerned about market returns, or wanting to hedge against inflation, the value of delaying Social Security remains about the same. However, because of how early benefit reductions are calculated for survivor benefits, the new rules actually do substantially reduce the value of delaying widow(er) benefits for surviving spouses – at least, if they're not also facing the Social Security Earnings Test!

History Of Social Security Full Retirement Age

Under the original Social Security Act of 1935, workers had to reach age 65 to receive a full retirement benefit. This “full retirement age”, though commonly attributed to a similar “old age social insurance” program designed by Otto von Bismarck in Germany in 1889, was actually simply rooted in the fact that many state pension systems (and also the then-recent Railroad Retirement Benefit system) used age 65, and the Committee on Economic Security (which designed the US Social Security system) decided to adopt what was already common practice.

The full retirement age remained at age 65 until 1983, when the Social Security Trust was about to run out of money (which would have caused an immediate partial cut to benefits), and the National Commission on Social Security Reform (also known as the “Greenspan Commission” after its chairman Alan Greenspan) recommended a series of adjustments to the system to extend its financial stability for another 50 years. The end result was the Social Security Amendments Act of 1983, signed into law on April 20th of that year (just a few months before the Social Security Trust Fund would have run dry), which made a wide range of changes to the Social Security system… including increasing the Social Security full retirement age from 65 to 67.

To soften the impact of the increase, the Greenspan Commission recommended a phased approach over time. Everyone who was already within 20 years of full retirement age (approximately age 45 or older at the time the law was passed) would get to keep the original full retirement age of 65. Those who were age 44 or younger – born in 1938 or later – would have to accept a higher full retirement age, but the phase-in would occur gradually over a 22-year period, with an 11-year hiatus in the middle. The end result was that only those aged 22 or younger in early 1983 – born in 1960 or later – would actually be subject to the new full retirement age of 67.

Given these birth years, the reality is that for more than a decade now – since 2005 – every prospective retiree, upon turning age 62 and becoming eligible for early retirement benefits, has had a full retirement age of 66 (as someone who turned 62 in 2005 was born in 1943).

However, the 11-year hiatus of full retirement age adjustments has now come to an end, as anyone turning 62 in 2017 was born in 1955, which means their full retirement age is no longer age 66. Instead, it is becoming age 66 and 2 months!

Social Security Early Retirement

The significance of the Full Retirement Age (FRA) is not merely that it’s the age at which retirement benefits become payable. Since 1956, women have been able to start benefits as early as age 62 (implemented at the time because wives on average were 3 years younger than their husbands and wanted to retire and start benefits at the same time), and the rule was expanded to allow men to retire early in 1961. However, to remain actuarially fair, Social Security stipulated that taking “early retirement” at age 62 would reduce benefits by 20%, which equates to 6.66%/year or 5/9ths of 1% for each month early.

With the increase in full retirement age, though, it suddenly becomes possible to retire more than 3 years early. Accordingly, the rules were adjusted to provide that any further early benefits – beyond the first 3 years – would be reduced at an additional 5%/year (or 5/12ths of 1% for each additional month). As a result, in recent years when the full retirement age was 66, the total early benefits reduction was 6.66%/year for the first 3 years early, and another 5% for the 4th year early, for a total reduction of 25%.

Delayed Retirement Credits For Waiting Past Full Retirement Age

Similar to the downwards adjustment for starting retirement benefits early, there’s also an increase for delaying retirement past full retirement age. Originally, these delayed retirement credits were miniscule, at just 1%/year for waiting, but 1977 Social Security amendments increased delayed retirement credits to 3%/year, and the 1983 Greenspan Commission amendments ultimately phased delayed retirement credits all the way up to 8%/year (or 2/3rds of 1% per month) for delaying past full retirement age.

As a result, with a full retirement age of 66, the maximum delay to age 70 would result in delayed retirement credits of 8%/year x 4 years = a 32% increase. (Notably, the 8%/year delayed retirement credits are simply cumulative, not compounded.)

Consequences Of The Increase In Social Security Full Retirement Age

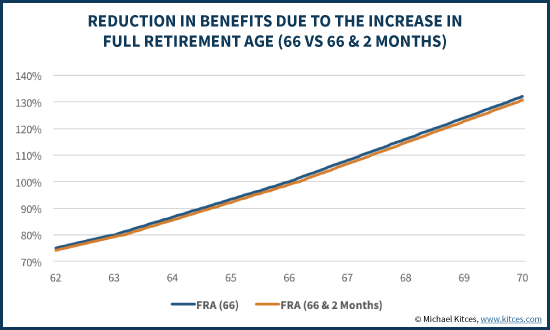

The significance of the increase in full retirement age from 66, to 66-and-2-months instead, is that now trying to take benefits at 66 is actually an “early” benefits election, resulting in a 1.1% reduction for starting payments 2 months before full retirement age.

For those who want to start as early as possible – at age 62 – doing so is no longer a decision to take benefits 4 years early. Instead, it’s 4 years and 2 months early, which means the age-62 benefits reduction is now 25.83% (instead of just 25%). Similarly, delaying to the maximum age 70 would not earn 4 years’ worth of Delayed Retirement Credits, but instead only 3 years and 10 months of DRCs, for a total increase of 30.67% (instead of the ‘full’ 32%).

The end result: benefits can never quite be as high as they were before at the maximum, and at any given age, Social Security benefits take a slight haircut.

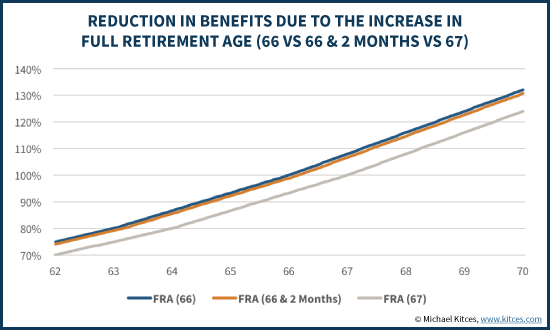

Notably, the impact of a rising full retirement age will continue from here for several more years as well. As noted earlier, the full retirement age is scheduled to go all the way to age 67 over the next 5 years, such that those born in 1960 or later – who start turning 62 in 2022 – will find when making their Social Security decisions that an age-62 starting date is a full 30% reduction, while delaying to age 70 is only a 24% increase.

Other Adjustments From The Increase In FRA – Spousal And Survivor Benefits

In addition to changes the consequences of taking early or late retirement benefits, the change in full retirement age also impacts spousal and survivor benefits as well.

In the case of spousal benefits, the standard rules stipulate that spousal benefits will be reduced by 8.33%/year (calculated as 25/36ths of 1% per month) for the first 3 years, and 5%/year for each additional year. Thus, it was originally the case that taking spousal benefits at age 62 was “just” a 25% reduction (at 8.33%/year for 3 years) when the full retirement age was 65, but starting at age 62 has been a 30% reduction for the past decade (when the full retirement age was 66), and beginning in 2017 the age-62 spousal reduction will be 30.83%, climbing to a maximum reduction of 35% in 2022 for those born in 1960 or later.

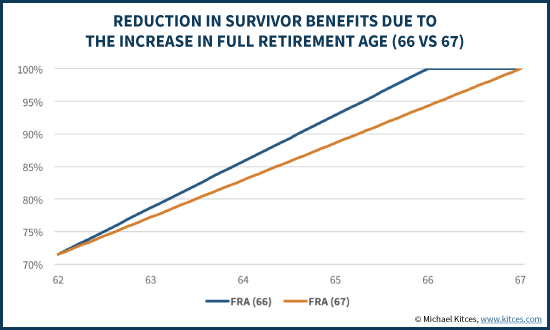

When it comes to survivor benefits, though, the rules are slightly different. Survivor benefits can be claimed as early as age 60, and the maximum reduction for starting survivor benefits that early is always a flat 28.5% reduction, applied pro-rata from the maximum retirement age back to age 60. Thus, for instance, in the original system when the full retirement age was 65, starting at age 60 was five years early, and the reduction was 28.5% / 5 years = 5.7%/year (or 0.475%/month). At full retirement age of 66, starting at age 60 is six years early, so the reduction is 28.5% / 6 years = 4.75%/year (or 0.396%/month). And when full retirement age ultimately goes to 67, the reduction will be 28.5% / 7 years = 4.07%/year (or 0.339%/month).

Notably, the end result of these rules is that for survivor benefits, it’s not any worse to claim survivor benefits at the earliest age 60 as the full retirement age increases (unlike for retirement and spousal benefits). In fact, by stretching out the same reduction over a longer period, it actually lessens the monthly impact of starting early (even as it increases the number of months that must be delayed to reach the full survivor benefit).

On the other hand, it's also important to recognize that full retirement age for survivor benefits is increasing on a different schedule than full retirement age for retirement and spousal benefits. For those who were born in 1955, where the full retirement age is rising to 66 and 2 months, the full retirement age for survivor benefits remains age 66, and only rises to 66 and 2 months for those born in 1957. In turn, the full retirement age for survivor benefits isn't only age 67 for those born in 1962 or later (as contrasted with retirement benefits, where full retirement age is 67 for everyone born in 1960 or later). As a result, for the next several years, prospective Social Security claimants will actually have to deal with two different full retirement ages - one for retirement and spousal benefits, and a slightly earlier (and more favorable) full retirement age for survivor benefits.

Financial Planning Implications Of The New Full Retirement Age

Ultimately, the reality is that for most retirees, there’s nothing to be “done” about the changes in the full retirement age. They’re a function of a law that was passed over three decades ago, which simply took until now (and the coming years) to finish their slowly-phased implementation, based on the retiree’s birth year. And obviously, there’s no way to change your birth year; for better or worse, you get what you get from here.

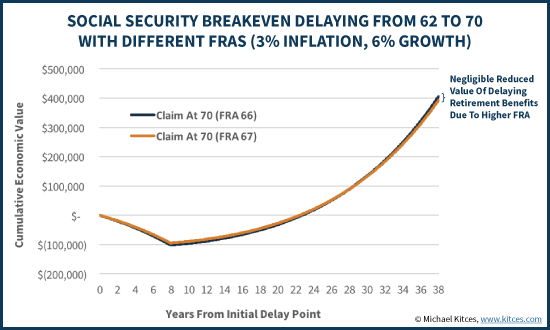

In addition, it’s important to recognize that while the increase in full retirement age makes the adverse consequences of starting at age 62 a little more severe (for retirement and spousal benefits) and the upside of waiting until age 70 less advantageous (for retirement benefits), it doesn’t materially change the relative value of waiting, and the breakeven period.

For instance, an individual with a $1,000/month retirement benefit at full retirement age of 66 could have enjoyed $750/month at age 62 (a 25% reduction) or $1,320/month at age 70 (a 32% increase). In the future, if that individual’s full retirement age goes to 67, it will be $700/month at age 62 (a 30% reduction for 5 years early), and $1,240/month at age 70 (a 24% increase for waiting 3 years). However, in both cases, it’s still an increase of about 76% to wait from age 62 to age 70, and the breakeven period is still about the same 20 year time period. Again, the primary impact of the changing full retirement age is not actually to alter the value of waiting, just to (slightly) reduce overall benefits.

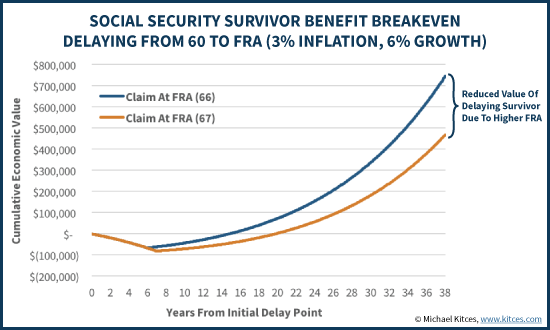

On the other hand, when it comes to survivor benefits, the changes to full retirement age (as it begins phasing in, in another two years) lessens the reduction for starting benefits early, which actually does make it less valuable to delay. In essence, if it takes another year of waiting to “undo” the full 28.5% early reduction, then it takes even longer to reach the breakeven period where the higher benefits outweigh the cost of waiting. Of course, it’s notable that when survivors have their own lesser retirement benefit, it may be beneficial to wait on survivor benefits until full retirement age, and claim individual benefits in the meantime (which can drastically reduce the breakeven period); nonetheless, at least on a standalone basis and when the Earnings Test won’t apply, later full retirement ages reduce the value of delaying survivor benefits, quite substantially.

In most situations, though, the key is simply to recognize the change that is underway, and that after more than a decade of the standard “age 66 is the full retirement age”, this is no longer the case, nor is it standard that starting at age 62 reduces benefits by 25%, nor that waiting until age 70 increase benefits by 32%. Instead, for those turning 62 this year in 2017, the shift is on, with full retirement age of 66 and 2 months, a 25.8% haircut for starting early, and a 30.7% increase for delaying… and the transition will continue until 2022, when all retirees born 1960 or later have a full retirement age of 67, a 30% maximum reduction for starting early, and only a potential of 24% in delayed retirement credits for waiting until age 70! And in the case of survivor benefits, the transition will continue even longer, as full retirement age becomes "disjointed" until 2024!

So what do you think? Will this adjustment in full retirement age impact any of your planning recommendations? Are clients aware of this change? How significant will the reduction in benefits be for those born in 1960 or later relative to current retirees? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Since the majority of people are taking SS at 62 or upon ending work I don’t think this will impact most people’s “planning strategies.” An interesting question to pose to clients (or ourselves) is what can we do (e.g. drop five pounds) to offset the two-month adjustment?

The interesting part to me of all this is do people really understand the pros and cons of this stuff. I mean how do you tell someone who worked physical labor for 30-40 years yeah to retire you have to keep working another 2 or 3 years? People break down. How does a 60+ year old physical laborer keep going? It’s funny but in the military there is a mandatory retirement age of 60 because of the physical demands of the job. Funny how the military can see after 60 for the majority of people physical labor is a problem, but the civilians can. I guess they expect that laborer somehow to suddenly get a degree.

And if they were doing physical labor what are the chances they will have planned for retirement or have a decent savings? So are we doubling down on this poor person just because they were not told what SS really was when they were growing up?

I don’t pretend to have a solution, but maybe saving and retirement understanding and planning should be something kids learn as early as possible. I know my parents taught me good saving habits in grade school and I had saved a few thousand by high school through interest and investments. They forced me to learn, but when I saw how I could earn money without working I was hooked. I don’t work in banking or finance, but I understand them and use them all the time to both save money and make money. I am truly thankful for this, but I can see if I didn’t have it I would be in the same boat as most others.

So, each of us effectively wrote a check to our Soc Sec retirement fund for about $5000 (the amount of the two months checks we won’t be receiving). Except that it’s not “our” fund and it will just be used to pay current benefits a la Charles Ponzi.

You can do anything for 2 months (like wait). Thanks for outlining the repercussions. The information is crucial to know as planners. If you’re born after 1960, unless there are dire circumstances to consider, taking SS early is not an option.

The biggest problem here is people believe Social Security Insurance is a retirement plan. It’s not. It’s an insurance plan so you don’t live on the street if you run out of retirement. The problem is people believe it is a retirement plan. I plan $0 of Social Security for my retirement because if I have to use it I failed to plan for retirement. Oh and I plan for my entire family, myself, my wife and started a retirement plan for my kid at negative 6 months old. I know that may sound odd for the kid, but just think how much with compounding interest do you need to save per month to have someone retire in 60+ years? Let me assure you it is probably less than what most people spend on coffee per day.

This failure to plan by the majority of Americans, the removal of pensions for most workers, people living longer, the rat in the snake of the baby boomers, less children in the US and people needing to retire earlier because while we live longer physical jobs are unrealistic after 62 has forced a rethinking of the system. This super storm of social, economic and actuarial changes made the need for change in the insurance plan happen in 1983. If no one read the bill then that is your fault. If you didn’t know SS was not really for retirement again read.

I am so sick of people complaining that they can’t live well off SS, you were never supposed to, it is a help to keep us from having a country overrun with destitute old people on the streets nothing more.

What do you believe the solution is? There are droves of baby boomers hitting retirement with the belief that they’ll be able to have the same standard of living that they had while working while they saved less than 10% of their annual income for retirement.

Their pension that was de-risked a decade ago? They rolled it to an IRA and subsequently used it to it build an addition onto their house or bought a boat (real examples I’ve seen). Many will take SSI at 62 and over-withdraw from their 401(k)’s.

Outside of our own clients (who are all obviously in perfect financial condition, right?), I expect there to be a very large group of folks that will run out of money in their 70’s and be required to drastically reduce their spending. I don’t mean to fear-monger, but that’s what I see. Many folks that are incredibly against governmental safety nets may be changing their tune in the next 10-20 years.

Well the solutions possible are many. The real question is political will. With a bi-polar electorate right now it stops a lot of change. By bi-polar I mean the Baby Boom population hump vs the Millineal hump. So I will sideline that discussion.

Pension de-risked is a problem, a family member got hit with this and is retiring soon with a much reduced retirement with considerably higher risk. I fell that you are correct about overdrawing 401k’s people are way too optimistic about the market and don’t account for normal market fluctuations which cause compounding problems during bad market years coupled with mandatory 401k withdraws.

Now how this will pan out is already happening. I see it every day working in charity. Older women who didn’t work and get crappy survivor benefits, high medicare costs and no cola raises. They work in the grey market to keep their income off the books so they don’t owe more or endanger their benefits. Overall this depresses wages and causes more problems. Food stamps, government housing assistance, etc will all be needed at minimum in the next few years to prevent some really bad stuff. Whether it will happen is a great question. This country is having serious polarization which may make the problem worse before it gets better. Inter-grenerational hate is at a fever pitch with younger generations angry at the older for taking all their opportunities and programs away in the name of lower taxes. It will be interesting to see how this plays out when the young are in charge and the old need the benefits. Being in gen X and the lowest birth year of gen X to boot all I can do is watch and give counsel because I have or will miss both issues.

These words of yours resonate with me. See why in the paragraph following this one : “This country is having serious polarization which may make the problem worse before it gets better. . Inter-grenerational hate is at a fever pitch with younger generations angry at the older for taking all their opportunities and programs away in the name of lower taxes. ”

In conversations with millennials and baby boomers, there is – as you note- intergenerational strife (resentment from millennials and defensiveness from baby boomers ).

But here’s the catch: when I ask millennials if they will turn their backs on their parents if they face financial ruin as they age , this gives most of them pause (at least those who had loving parents who spent much time and money to raise them well) .

They can maintain their anger when they focus on the general sense of betrayal towards baby boomers taking away opportunities. But when they think about their own parents, love often trumps anger and they act accordingly.

I understand both sides and -as a baby boomer – have been frugal enough to save more than recommended, including extra for long-term care. I never want to depend on my children.

I also feel for them because they struggled after college, in spite of excellent grades at good universities , to land jobs which would support them..as did many of their peers . I am extremely grateful they are doing well – but not nearly as well as I did at their age. I did not have a better education. They simply faced different employment opportunities ( one started law school just before jobs began drying up)

I feel exactly the same way as GregT.

There will be many, many people who are in for a rude awakening and will have to substantially reduce their standard of living in retirement because they did not save enough during their working years.

Partly to blame for this (I think) is that baby boomers have seen their parents and grandparents retire and get by just fine. However, those who will end up “short” likely have not considered the fact that (1) their parents and grandparents may well have had a defined benefit pension plan (most of us today do not) and (2) their parents and grandparents lived well within their means during their working years and continued that behavior into retirement. Today, many baby boomers (of which I am one) live in the moment and live at the limit of or beyond their means, finding ways to finance that and never thinking there will be a day of reckoning. It’s a “we will figure it out or cross that bridge when we get there meantality”. Well, unfortunately for them there will. And I worry that this will somehow impact those of us who behaved responsibility, lived within our means and saved appropriately for retirement.

Mike I am worried that new financial policies and a time based problem that is about to hit may aggravate this problem. If we want to build a wall, do a 1 trillion dollar infrastructure project, increase defense spending by up to 200 billion per year, etc. This is coupled with the fact given from the CBO yesterday that while we have a very reasonable budget deficit right now it will go nuts in 2018 and then get totally out of control by 2027 even if WE DO NOTHING to increase spending. So to add all this together would accelerate the deficit increase to above 5% which causes all kinds of problem structurally.

By structurally I mean inflation and not the happy slow kind like we have had for the past 30 years I mean the 1970’s style double digit type. Which means the SSI people want will be worth even less than it is now. So we will go into money printing mode which never ends well.

So bottom line unless there is some serious change to SSI, Medicare and Medicaid were going to learn what hyper-inflation looks like. But I doubt there is the political will to make the real sacrifices. These include any number of possible fixings: Raising the cap on SSI taxable income, raising the amount taxes for SSI, decrease payments, limit it more than it already is by offset income, etc etc. And that is only SSI we have not even talked about Medicare or Medicaid.

If you look at the spending in 2017 Pensions which SSI is under is 25% of the federal budget, Healthcare is 28%, Defense is 21%, Welfare is 9% and interest is 7%. So that is 90% of the budget. EVERYTHING else is just 10%. So the fact is there is really no where else to look to take from. So because everyone waited to fix this for 30 years we are now in a real budget mess and there is no quick fix.

Excellent points. In addition, let’s not forget the history of this “insurance policy”. When implemented, the life expectancy was equal to the FRA. Social Security essentially started out as longevity insurance. We’ve come a long way from that thinking and we’d be best served to return to that kind of thinking.

Ah,,, if only the fed’s could also legislate an equivalent delay in the actuarial life expectancy! Michael’s article has motivated me to redo some calculations I did several years ago based upon an FRA of 66. Modeling SSA benefits as a single-payment annuity: purely from an investment perspective based upon the Internal Rate of Return, the best strategy is to file at FRA. My initial guess is that the advancing age of FRA would make delayed filing even less “profitable,” unless of course, we’re also granted an additional two months of life with each increment of FRA.. Interesting discussion as usual..

You have an interesting perspective, and it would seem your advice is contrary to most others’. Do you have some data posted publicly somewhere that supports your recommendation?

Thanks!

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0B40q84N3peOtdzA1dTF0VzF4Tjg

Here’s are example scenarios in spreadsheet format, based upon hypothetical returns for husband/wife, same age. Scenario one: both file at FRA. Scenario 2: husband files and suspends at FRA; wife gets spousal at FRA; both file for full accrued PIA at 70. You can see that based upon IRR, when returns are modeled as a single payment annuity, immediate filing provides a better return. The SSA PIA amounts were calculated using SSA’s “AnyPIA” program, available at their site. Using this program, any number of scenarios can be investigated. I’ve looked at many, but the results are uniformly that “file at FRA” gives the best return.

Thanks for making that available. Models and data are good: “The fundamental principle of science, the definition almost, is this: the sole test of the validity of any idea is experiment.”

— Richard P. Feynman

Hi Mike, Late question. When they say age 66 and 2 months does the birthday month count as month 1 or is it the month after the birthday month that counts as month 1? I was born in 1955 and my B-Day is in mid-June. What month would I be eligible to begin drawing my FRA? Thanks Thumper