Executive Summary

Solo 401(k) plans are a popular retirement savings vehicle for self-employed business owners. One of their key features is the ability to make contributions both as an "employee" of the business and as the "employer", i.e., the business itself. By maximizing both the employee employer contributions, solo 401(k) plan owners can often save significantly more than is possible with other types of retirement plans available to self-employed workers, like SEPs and standard IRAs.

The tax treatment for solo 401(k) plan contributions can range from traditional (pre-tax) to Roth to after-tax (i.e., a nondeductible contribution that can be converted to Roth tax-free). With the caveat, however, that the types of tax treatment available depend on whether the funds are coming from the "employee" or "employer" part of the contribution. Employee contributions can be made on a pre-tax, Roth, or after-tax basis, or a combination of all three. But historically, contributions from the employer side could only be made on a pre-tax basis.

In 2022, the SECURE 2.0 Act included a provision that changed the rules for 401(k) plans (including solo 401(k)s) that for the first time allowed employer contributions to be made on a Roth basis. Although the rule technically took effect immediately after SECURE 2.0's passage, it took until late 2023 to issue guidance on how Roth employer contributions should be reported for tax purposes.

According to the IRS's guidance, Roth employer contributions to a 401(k) plan are effectively required to be reported as if the contribution had been made on a pre-tax basis, and then immediately converted to Roth. Which makes sense in that it doesn't require wholesale changes to existing tax forms or payroll systems, but does have an unintended side effect for self-employed owners of solo 401(k) and SEP plans who are also eligible for the Sec. 199A deduction for Qualified Business Income (QBI): Because the business's QBI is reduced by the amount of any deductible retirement plan contribution, the fact that Roth employer contributions are reported initially as deductible contributions mean that they reduce the business owner's Sec. 199A deduction, even though they don't actually reduce their taxable income (since the income from the Roth contribution is added back in the form of the "phantom" Roth conversion as required by the IRS's guidance).

Accordingly, business owners who contribute to a solo 401(k) or SEP plan and are also eligible for the Sec. 199A deduction may want to avoid making Roth employer contributions, even if their plan provider allows it. Fortunately, however, there is another way to maximize Roth contributions to a solo 401(k) plan that doesn't affect QBI in any way: If the plan allows employee contributions to be made on an after-tax basis, the business owner can simply make after-tax contributions (all the way up to the $69,000 total contribution limit) and convert them to Roth, which is a tax-free transaction since the contributions weren't deductible to begin with. And because there's no deduction for the contribution, it won't affect the QBI calculation in any way.

The key point is that, as business owners decide on their solo 401(k) contributions for the year, they may be unaware of the effects that making Roth employer contributions might have on their Sec. 199A deductions. For advisors, then, making sure that business owners clients are aware of these effects, and giving guidance on how to work around them via after-tax employee contributions, can ensure that they get the maximum benefit from their Roth solo 401(k) savings!

When a business sets up a 401(k) plan for its employees, there are broadly two kinds of contributions that can be made to the plan. First, employees can make contributions themselves, by choosing to defer some portion of their paycheck into the plan. Second, the employer can make additional contributions on its employees' behalf, which come from profits of the business itself rather than the wages or salaries of its employees. The total amount added to each employee's account annually is the sum of the employee's contributions plus the employer's contributions.

Similarly, when an individual is self-employed rather than working for another employer, they also have the ability to set up a 401(k) plan for their own business. A "solo 401(k)" plan is a particular type of retirement plan designed for self-employed individuals with no other employees. By definition, solo 401(k) plans are those that cover only the business owner (and, in some cases, the owner's spouse if they also earn income from the business).

Solo 401(k) plans have a few specific rules that set them apart from 401(k) plans offered by larger employers. For instance, solo 401(k) plans aren't subject to the "top-heavy" testing rules designed to ensure that a business's 401(k) plan benefits aren't skewed in favor of its highly compensated employees, since a solo 401(k) plan by definition doesn't cover any employees other than the business owner themselves. Likewise, solo 401(k) plans aren't subject to ERISA rules that impose numerous fiduciary responsibilities on retirement plan sponsors and administrators.

In most other ways, however, solo 401(k) plans function just like any other 401(k) plan offered by a larger business. Namely, just as larger employer plans split contributions between employee and employer contributions, a solo 401(k) plan also splits its contributions between those made by the "employee" and those made by the "employer" – even though, as a self-employed individual, the employee and the employer are effectively the same person.

This "split-contribution" feature of solo 401(k) plans makes them a popular choice of retirement plan for self-employed individuals, as the combination of both employee and employer contributions often allows for higher contributions compared to a Simplified Employee Pension (SEP) plan, which only permits employer contributions. But because the two different contribution types each have their own rules and limits on the amounts that can be contributed, determining how much a business owner can contribute to their solo 401(k) often requires them to make separate calculations of their "employee" and "employer" contributions each year to add up to their maximum total contribution limit.

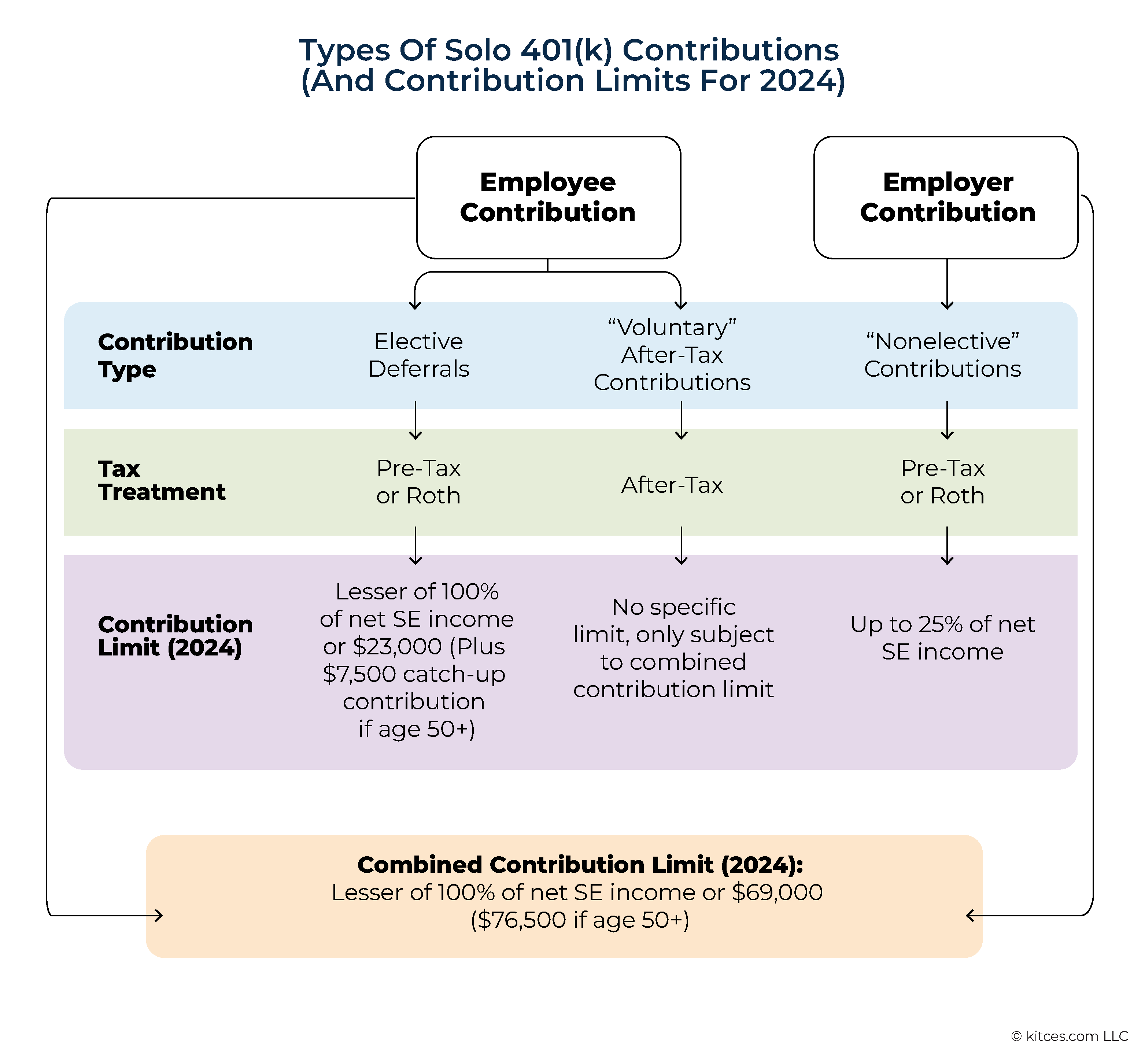

Employee Contributions

Employee contributions to a solo 401(k) plan can be further broken down into two separate categories: 1) elective deferrals that are made on either a traditional (pre-tax) or Roth basis, and 2) "voluntary" after-tax contributions that are nondeductible but can be subsequently rolled over into a Roth account tax-free. For elective deferrals, the maximum contribution for 2024 is up to the lesser of 100% of net self-employment income or $23,000, plus an additional $7,500 catch-up contribution for those age 50 or older.

Nerd Note:

Net self-employment income, for the purposes of a solo 401(k) plan contribution, is calculated in different ways depending on whether the business is taxed as a sole proprietor, a partnership, or an S-corporation. For sole proprietors, net self-employment income is the business's net Schedule C income minus one-half of the self-employment tax attributable to that business; for partners, it's their K-1 income minus one-half of the self-employment tax attributable to the partnership; and for S-corporations, it's the total amount of W-2 wages paid as ‘reasonable compensation' to the owner/employee.

In contrast to elective deferrals, voluntary after-tax contributions have no specific maximum contribution amount. The only limitation is that the total amount of all contributions to the plan – elective deferrals, voluntary after-tax contributions, and employer contributions – can't exceed $69,000 in 2024 (plus the additional $7,500 catch-up contribution after reaching age 50). So in effect, the maximum amount of after-tax contributions that can be made is $69,000 (plus the catch-up contribution, if applicable) minus the total of elective deferrals and employer contributions made to the plan for that year.

Employer Contributions

On the employer side, the maximum solo 401(k) plan contribution is up to 25% of net self-employment income, which can be made in addition to the employee contributions described above – again, with the caveat that the total combined contributions can't exceed $69,000 in a single year.

Nerd Note:

There's a key difference between sole proprietorships and S-corporations in how the maximum employer contribution is calculated. For sole proprietors, IRS rules require the employer contribution rate to be adjusted to account for the reduction in business income due to the contribution itself. As a result, the effective maximum contribution for sole proprietors is 25% ÷ (1 + 25%) = 20% of net self-employment income. S-corporation owner-employees don't need to make the adjustment to their contribution rate, so for them the maximum contribution is 25% of the W-2 wages paid to the owner/employee.

Example 1: Bruce, age 53, is a self-employed S-corporation owner who paid himself $200,000 in W-2 wages this year. He wants to know how much in total he can contribute to his solo 401(k) plan.

For his employee elective deferrals, Bruce can contribute up to $23,000, plus a catch-up contribution of $7,500, for a total of $30,500.

For his employer contribution, Bruce can contribute an additional amount of up to 25% of his W-2 wages, or 25% × $200,000 = $50,000.

Combining both the employee and employer contributions adds up to $50,000 + $30,500 = $80,500. However, Bruce's total contribution is limited to $69,000 (the combined contribution limit) + $7,500 (the additional catch-up contribution) = $76,500.

Historically, employer contributions to 401(k) plans could only be made on a pre-tax basis, unlike employee contributions, which could be made on a traditional (pre-tax), Roth, or after-tax basis.

The reasons for the pre-tax-only restriction on employer contributions were mainly practical and administrative in nature. For example, if a company made Roth employer contributions to its 401(k) plan, those contributions would need to be included in their employees' income for income tax purposes – but not for the purposes of payroll taxes (i.e., Social Security and Medicare taxes), from which employer 401(k) contributions are generally exempt. Which potentially would have required a redesign of tax forms like the W-2 and a reconfiguring of the systems that employers use to calculate and report on their employees' income and tax withholdings. Restricting employer contributions to pre-tax only ensured that all employer contributions would be excluded from both income and payroll tax for employees, and that employers wouldn't be required to implement new systems to account for the tax treatment of Roth employer contributions as distinct from standard wage income.

The SECURE 2.0 Act And Roth Employer Contributions

Despite the practical challenges of implementing Roth employer contributions, Congress included a provision in the SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022 that amended IRC Sec. 402A, which gives employees the ability make Roth elective deferrals to their 401(k) accounts, to extend the Roth option to employer contributions as well. Meaning that now, as shown in the graphic below, both employee and employer contributions can be made on either a pre-tax or Roth basis, with after-tax contributions remaining an option for employees as well.

The SECURE 2.0 Act's Roth employer contribution provision technically went into effect immediately upon the law's enactment in the closing days of 2022. However, at that time there were few, if any, employers or 401(k) plan providers whose systems and processes were ready to immediately allow Roth employer contributions. Additionally, there was initially little guidance on how Roth employer contributions should be reported for tax purposes, including whether changes would be needed on tax forms like the W-2 to facilitate that reporting. As a result, despite Roth employer contributions technically being allowed as a matter of law, it's been rare to see them actually available in practice since SECURE 2.0's passage.

Some guidance on how to implement Roth employer contributions finally came in late 2023 with the publication of IRS Notice 2024-2. The Notice covers a number of miscellaneous SECURE 2.0-related topics, but buried way down on page 76 of 81, under Q&A L-9, is the long-awaited answer for how employer Roth contributions will need to be reported for tax purposes going forward.

At a high level, rather than requiring wholesale changes to Form W-2 and employer payroll systems as many had feared would be the case, the IRS's guidance in Notice 2024-2 represents a workaround that puts the onus of reporting Roth employer contributions on retirement plan custodians, rather than employers themselves.

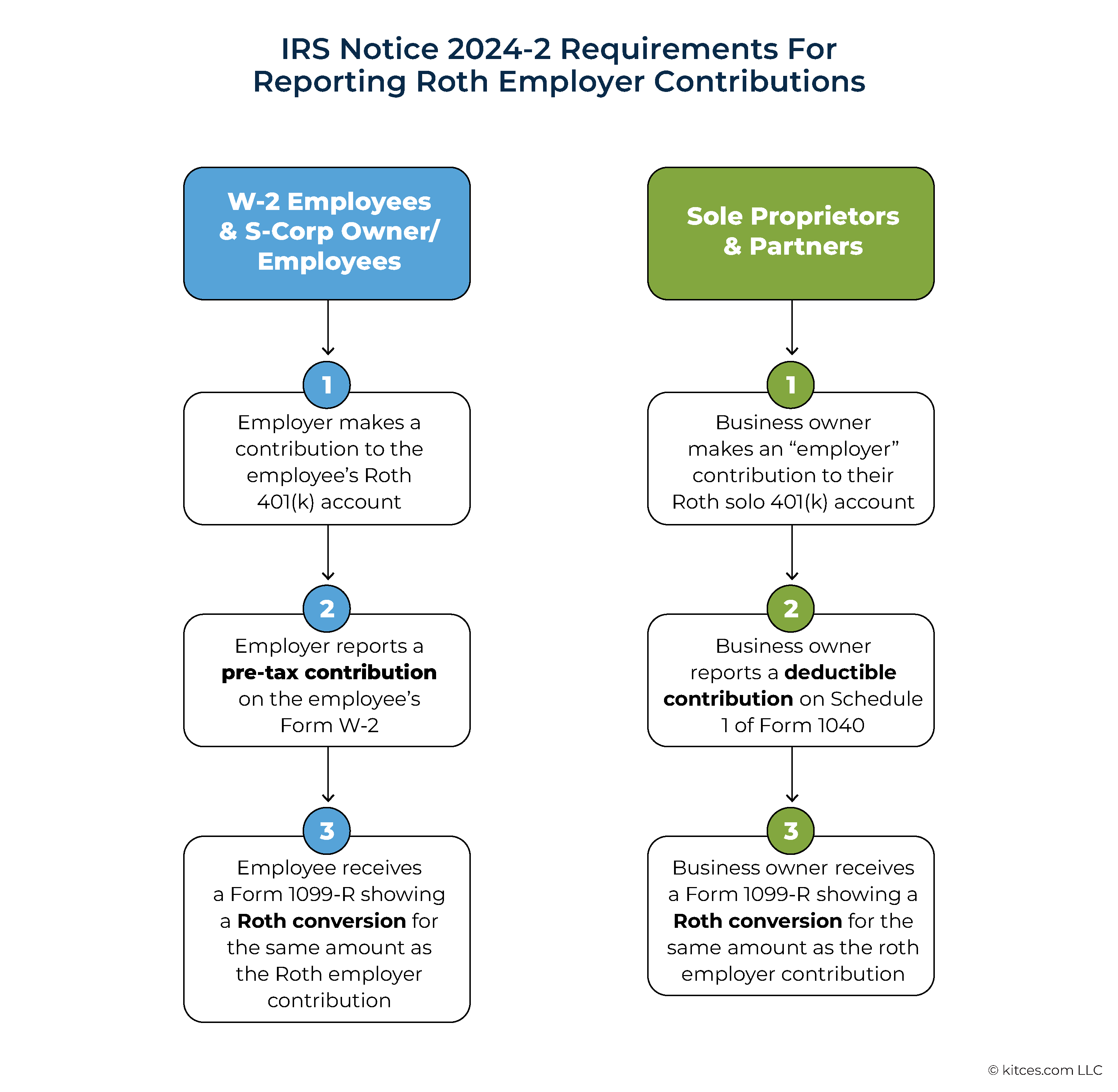

Specifically, the IRS's guidance states:

The reporting obligations that apply to a designated Roth matching contribution or designated Roth nonelective contribution are the same as if: (1) the contribution had been the only contribution made to an individual's account under the plan, and (2) the contribution, upon allocation to that account, had been directly rolled over to a designated Roth account in the plan as an in-plan Roth rollover. Thus, designated Roth matching contributions… must be reported using Form 1099-R for the year in which the contributions are allocated to the individual's account.

Put more simply, employer Roth contributions are treated in exactly the same way as if the employee had received a traditional pre-tax employer contribution and then immediately converted it to Roth. For W-2 employees (which includes S-corp owner/employees), the Form W-2 that they receive from their employer will show a pre-tax employer contribution. And for sole proprietors and partners with solo 401(k) plans, they'll report their employer contributions as a deductible contribution on Schedule 1. Except in both cases, the employee will also receive a 1099-R from their plan's custodian showing a Roth conversion for the same amount as the employer contribution, effectively adding back the ‘missing' income from the Roth employer contribution.

Setting aside the added complexity and potential confusion that this setup creates for employees receiving Roth employer contributions ("Why did I get a 1099-R showing a Roth conversion when I didn't do a Roth conversion this year?"), as well as the potential need for employees to increase their tax withholdings and/or make estimated tax payments to pay income tax on the Roth employer contribution, the ramifications of Notice 2024-2 are even worse for solo 401(k) plan participants who were planning to take advantage of the opportunity to make Roth employer contributions to their own plans.

Solo 401(k) Plan Contributions And The Section 199A Deduction For Qualified Business Income (QBI)

One thing many solo 401(k) plan participants have in common is that they're also eligible for the Section 199A deduction for Qualified Business Income (QBI). IRC Section 199A, created as part of the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act of 2017, allows owners of eligible pass-through businesses, including sole proprietors, partnerships, and S-corporations, to take a below-the-line deduction of up to 20% of the lesser of their QBI or their taxable income. And because sole proprietors, partners, and S-corporation owner-employees also make up most of the people contributing to solo 401(k) plans, it's very common for these plan participants to also take the Section 199A deduction.

There's already a somewhat complicated relationship between solo 401(k) plans and the Section 199A deduction. Because the QBI that's used to calculate the deduction is based on the business's net income, any deductions that reduce net income also serve to reduce the QBI deduction. And as the IRS made clear in Treasury Regulations 1.199A-3(b)(vi), a business's QBI is reduced dollar-for-dollar by the amount of any deductible contribution by the business to a qualified retirement plan. Which means that for every $1 of deductible retirement contributions made, the Section 199A deduction is reduced by 20 cents, resulting in a net deduction of only 80 cents for each dollar contributed.

Example 2: Amanda is self-employed as a graphic designer, earning $150,000 in net income from her business. She decides to make a $23,000 deductible contribution to her solo 401(k) plan this year.

Without this contribution, Amanda would have received a Section 199A deduction of 20% × $150,000 = $30,000 this year. However, since the contribution reduces the income that's used to calculate the deduction, her actual Section 199A deduction will be 20% × ($150,000 – $23,000) = $25,400.

In other words, by making a deductible contribution of $23,000, Amanda has also reduced her QBI deduction by $4,600, resulting in a ‘net' deduction for her solo 401(k) plan contribution of $23,000 − $4,600 = $18,400. Which is only 80% of her actual contribution!

As a result, the benefits of making deductible contributions to solo 401(k) plans have been diminished greatly since TCJA became law. Because any deductible contribution that a business owner makes to these plans also effectively reduces the Section 199A deduction they receive, the contribution is no longer truly fully deductible – the actual deduction they receive is only 80% of the actual dollars contributed.

How Roth Employer Contributions Reduce The QBI Deduction

For many Section 199A-eligible business owners, the diminished benefits of pre-tax solo 401(k) plan contributions due to the QBI deduction have shifted the focus toward making Roth contributions. Even for relatively high-income business owners, it can often make more sense to pay tax on a Roth contribution now – at a lower marginal rate due to the QBI deduction – and enjoy tax-free withdrawals of contributions and growth later on. By contrast, pre-tax contributions provide only an 80% deduction (due to the QBI adjustment) that will still be 100% taxable upon withdrawal.

But the SECURE 2.0 Act's provision for making Roth employer contributions and the subsequent IRS reporting guidance add yet another wrinkle to the relationship between solo 401(k) plans and the Section 199A deduction.

As explained above, Roth employer contributions must first be reported by the business owner as a deductible contribution to the employee's pre-tax 401(k) plan account, followed immediately by a Roth conversion and rollover to their Roth account. Which means that the Roth employer contribution is treated the same way as a pre-tax contribution for reporting purposes, even though it was never intended to be pre-tax. The non-deductible nature of the Roth contribution is reflected on a Form 1099-R showing a Roth conversion in the amount of the employer contribution, which is issued by the plan recordkeeper at the end of the year.

For regular (non-self-employed) employees, this reporting method is fine because the reported pre-tax contribution and immediate Roth conversion effectively cancel each other out, making zero net difference in the employee's taxable income. The only real downside is the administrative hassle of tracking another tax form and reporting a ‘phantom' Roth conversion on Form 1040.

However, for business owners who contribute to solo 401(k) plans and are eligible for the Section 199A QBI deduction, the IRS's ruling very much makes a difference. Because Roth employer contributions are reported as deductible contributions, and because deductible solo 401(k) plan contributions reduce the business's QBI, Roth employer contributions reduce the business owner's QBI, and thus their Section 199A deduction.

Even though the income is later ‘added back' on the owner's tax return by the Roth conversion reported on Form 1099-R, this income does not restore the business owner's lost QBI. Effectively, the contribution is treated the same as if the owner had made a deductible employer contribution and later elected to convert those funds to Roth, which has the same net effect of reducing QBI while being taxed for the full amount of the ‘conversion'.

Put more simply, for solo 401(k) plan owners, Roth employer contributions reduce the Section 199A deduction and increase taxable income without actually adding or subtracting any income!

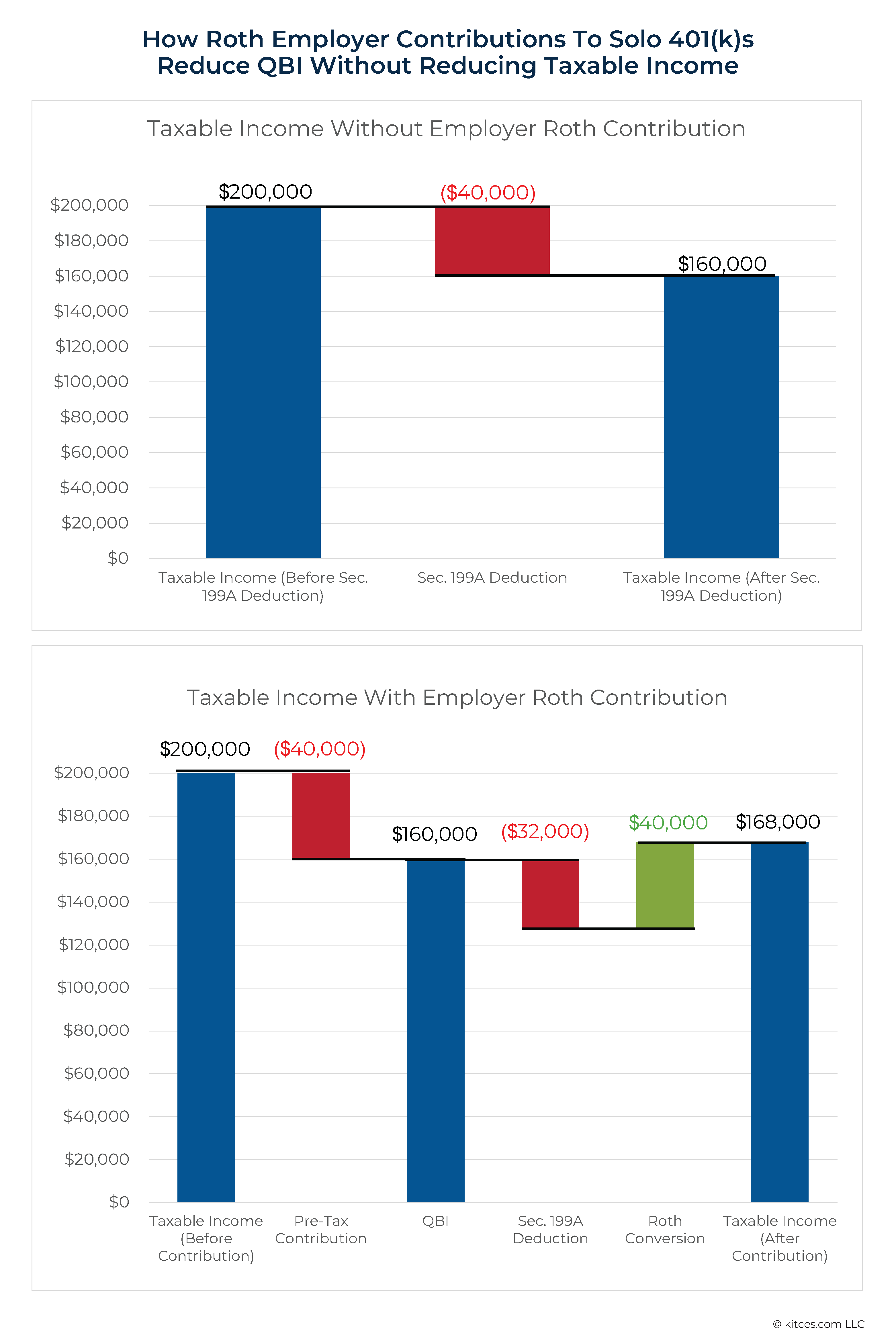

Example 3: Cynthia, age 40, is a sole proprietor who has $200,000 of net self-employment income this year. She expects her tax rates to go up in the future, and therefore wants to maximize her Roth contributions to her solo 401(k) plan this year.

Cynthia can make up to $23,000 in Roth elective deferrals this year. Additionally, she can contribute up to 20% × $200,000 = $40,000 in Roth employer contributions.

Assuming Cynthia's QBI is the same as her net self-employment income of $200,000, Cynthia's Section 199A deduction without the plan contributions equals 20% of her $200,000 of QBI, or 20% × $200,000 = $40,000. But while her Roth elective deferrals don't affect her QBI deduction at all, her Roth employer contribution is reported as a $40,000 deductible contribution, which reduces her QBI to $200,000 − $40,000 = $160,000. As a result, her Section 199A deduction is 20% × $160,000 = $32,000.

So even though the Roth employer contribution itself has no effect on Cyntha's taxable income – because it's reported as a deductible contribution, with the income added back in the form of a 1099-R showing a Roth conversion for the same amount of the contribution – it still ends up indirectly increasing her taxable income by reducing her Section 199A deduction.

As shown below, the net effect for a business owner with $200,000 in QBI making a $40,000 Roth employer contribution to a solo 401(k) plan is a $40,000 reduction in QBI, leading to a 20% × $40,000 = $8,000 reduction in their Section 199A deduction, and a corresponding $8,000 increase in their taxable income.

While the Sec. 199A deduction was originally planned to sunset along with the rest of TCJA at the end of 2025 – which would have only made this a problem in 2024 and 2025 – the incoming Republican trifecta government makes it exceedingly likely that the Section 199A deduction will be extended (or even expanded) into future years. Meanwhile, as more payroll and 401(k) plan recordkeepers begin to incorporate the IRS's guidance and offer Roth employer contributions in their plans, there will inevitably be more interest among solo 401(k) plan participants in making Roth employer contributions.

It seems unlikely that the IRS intended for their guidance on Roth employer contributions to have negative tax consequences on self-employed workers contributing to their own retirement plans, and it's possible that they could issue guidance at some point that changes the reporting rules for Roth employer contributions at least for self-employed taxpayers. But the rules as they're written today are pretty clear that a Roth employer contribution to a SEP or solo 401(k) plan is to be reported as a deductible contribution followed by a Roth conversion, which means that the contribution reduces QBI for the purposes of the Section 199A deduction.

For advisors, this means that it's important to be aware of the possible downsides of Roth employer contributions in solo 401(k) plans (as well as SEP plans, which have the same employer contribution rules) and to guide clients toward other strategies that can accomplish the same goals without negatively impacting their tax situation.

Using Elective Deferrals And After-Tax Contributions To Add Roth Savings To A Solo 401(k) Plan

Thankfully, despite the unexpected tax pitfall created by the interplay between Roth employer contributions to a solo 401(k) plan and the Section 199A deduction, there are other methods that are just as effective at adding Roth savings, but without the corresponding increase in taxable income.

As discussed earlier, solo 401(k) plan participants can make Roth elective deferrals of up to the lesser of 100% of their net self-employment income or $23,000. For anyone planning to contribute $23,000 or less, then, the best method is to simply make elective deferrals to the Roth portion of the plan.

However, there are two main caveats to this approach: The first is that the $23,000 cap on elective deferrals for a solo 401(k) plan is far less than the overall contribution limit of $69,000, so if someone wants to contribute more than $23,000 in Roth savings, the elective deferral route will leave them short. The second caveat is that if a participant also contributes to other 401(k), 403(b), or most 457 plans – e.g., as someone who is a regular W-2 employee at one job and is self-employed on the side – they may not be able to contribute as much (or at all) because the $23,000 limit on elective deferrals applies across all plans, not to each plan individually.

For those planning to contribute more than $23,000, or whose elective deferrals are limited by contributions to another plan, making ‘voluntary' after-tax contributions to the solo 401(k) plan may be a better option.

After-tax contributions, as the name implies, are those that don't receive a deduction upon contribution. If the after-tax dollars stay in the account, the contribution itself can eventually be distributed tax-free, but any growth is taxable upon withdrawal.

Usually, however, the point of making after-tax contributions is not to keep them in an after-tax account, but to convert them to Roth, either to the designated Roth account in the 401(k) plan or to an outside Roth IRA. When after-tax dollars are converted to Roth, the principal portion of the conversion gets rolled into the Roth account, while any accumulated growth on the contribution can be split off from the principal and moved to a traditional pre-tax IRA. As a result, there's no tax paid at the time of the conversion, since the principal portion already consists of after-tax dollars and is nontaxable when converted to Roth, while the rollover of the growth portion to a traditional IRA keeps the tax-deferred treatment of those dollars.

Traditionally, this method of making after-tax contributions to a 401(k) plan and subsequently converting them to Roth has been done as part of the so-called "Mega Backdoor Roth" strategy. This approach is often used when the participant has already maxed out their elective deferrals and any available employer contributions, but still has room for additional contributions up to the $69,000 combined contribution limit.

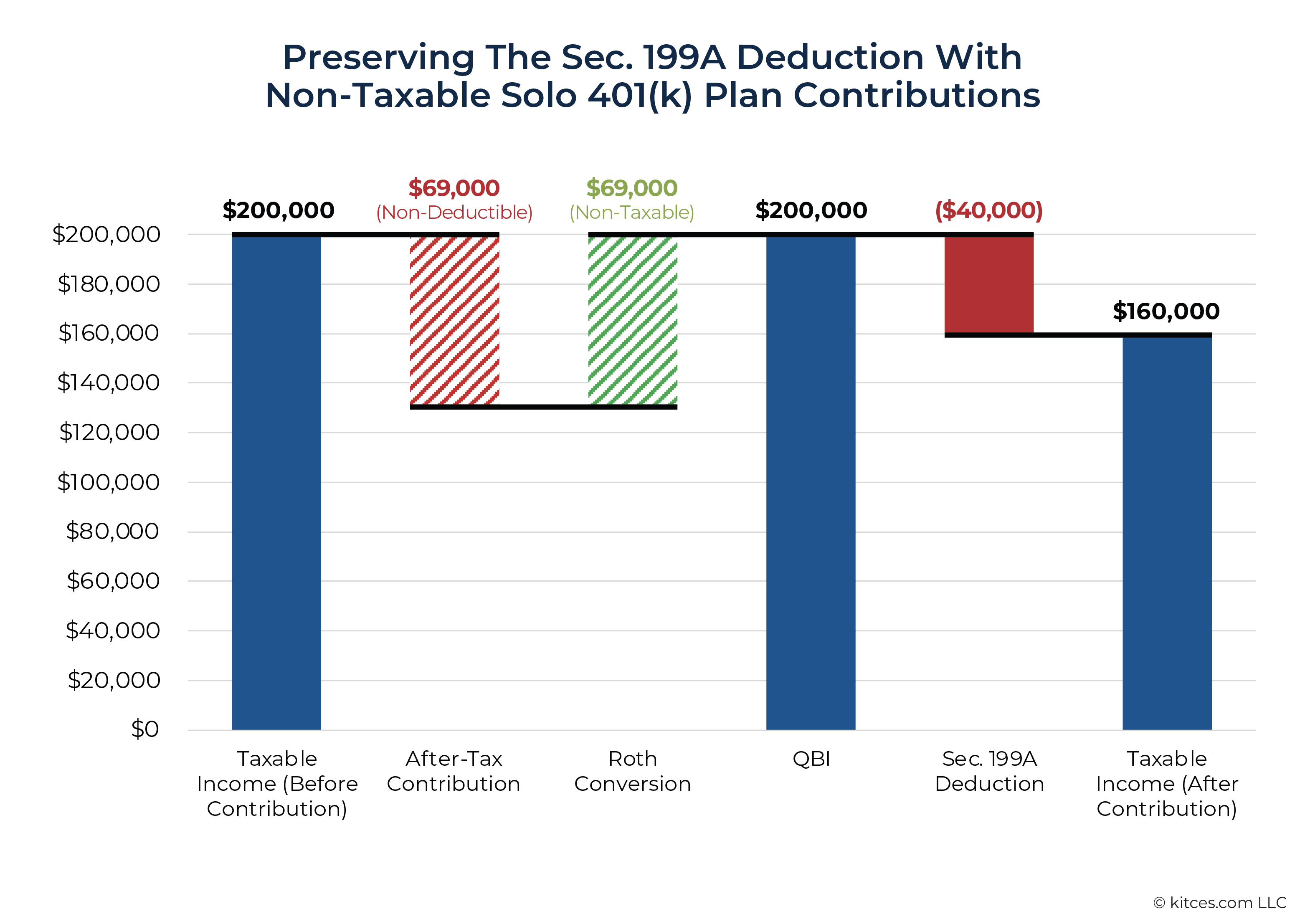

But for solo 401(k) plan participants eligible for the Section 199A deduction, making only after-tax contributions may be better than waiting to make them until hitting both their elective deferral and employer contribution limits. Because unlike Roth employer contributions – which are reported as a deductible contribution followed by a Roth conversion and thereby decreases the business owner's QBI and Sec. 199A deduction – after-tax contributions are never reported as deductible to begin with. As a result, there's no subsequent reduction in QBI, and thus no effect on the Sec. 199A deduction.

For example, a business owner with $200,000 in QBI who makes $69,000 of after-tax contributions to a solo 401(k) plan, then converts the entire contribution to Roth, experiences no change on their QBI – it remains at $200,000 both before and after the after-tax contribution and subsequent Roth contribution, as illustrated below:

The kicker is that, other than the impact on the Section 199A deduction, there's almost zero difference from a tax perspective between making a Roth elective deferral (or employer contribution) and making an after-tax contribution followed by a Roth conversion. In both cases, the funds end up in the participant's Roth account – the only difference is that Roth employer contributions reduce the business owner's Section 199A deduction, while after-tax contributions followed by a Roth conversion do not.

From a simplicity standpoint, solo 401(k) plan participants might find it more practical to make their entire contribution – up to $69,000 in total – as an after-tax contribution. While it's possible to make elective deferrals directly to the Roth account and then contribute additional dollars as after-tax contributions, the end result is the same: the funds are deposited in the Roth account either way. So why make two different types of contributions when the same result can be achieved with just one?

Knowing Which Business Owners Should Make Pre-Tax, Roth, And After-Tax Solo 401(k) Plan Contributions

The issue with Roth employer contributions to SEP and solo 401(k) plans stems not from the contributions themselves but from how their reporting affects the business owner's Section 199A deduction. As such, it's really only a concern for business owners who are eligible for the Section 199A deduction to begin with. And while most self-employed individuals qualify for the Section 199A deduction, not all of them do. For the relatively small subset of self-employed SEP and solo 401(k) plan participants who aren't eligible, Roth employer contributions pose no risk of reducing the Section 199A deduction, because there's no deduction to reduce.

High-Income SSTB Owners

The main reason a self-employed person wouldn't be eligible for the Section 199A deduction is that they are a high-income owner of a Specialized Service Trade or Business (SSTB). SSTBs include professions like consultants, lawyers, health professionals, accountants, financial advisors, and others whose business relies mainly on the skill and/or reputation of their employees. For SSTB owners, the Section 199A deduction phases out at higher levels of taxable income.

For 2024, the phaseout ranges are between $383,900 and $483,900 of taxable income for joint filers and between $191,950 and $241,950 for single and all other filing statuses. Households whose taxable income exceeds the upper threshold are entirely phased out of the deduction.

Implications For Roth Employer Contributions

For SSTB owners whose income disqualifies them from the Section 199A deduction, there's no harm in making Roth employer contributions to a SEP or 401(k) plan, since there's no Section 199A deduction to reduce to begin with. The catch-22, however, is that households with taxable income exceeding the phaseout range are typically in the 32% Federal tax bracket or higher, making deductible pre-tax contributions more advantageous than Roth retirement contributions – especially when doing so will reduce the household's taxable income enough to phase them back into the Section 199A deduction.

In other words, the self-employed business owners who wouldn't be negatively impacted by Roth employer contributions are often those for whom Roth contributions don't make financial sense in the first place. Still, higher-income SSTB business owners who expect their tax rates to increase even further in the future may nevertheless prefer making Roth contributions to their SEP and solo 401(k) plans despite their current tax bracket. If and when they do so, the fact that they're not eligible for the Section 199A deduction means that there will be no reporting issues with employer Roth contributions.

Taxable Income-Limited QBI Deductions

Another scenario where Roth employer contributions to a SEP or solo 401(k) plan wouldn't impact the Section 199A deduction arises when the deduction is limited by taxable income rather than QBI.

Recall that the Section 199A deduction is calculated as 20% of the lesser of the taxpayer's QBI or their taxable income. In situations where taxable income results in the lower of the two amounts, it won't matter if Roth employer contributions reduce QBI since the calculation is based on taxable income.

This situation often occurs when an individual's business income constitutes most or all of the taxpayer's income, and when they have large deductions outside of the business (e.g., itemized deductions like mortgage interest, medical expenses, or charitable donations; or deductible losses from rental properties or other businesses). For business owners in these circumstances, Roth employer contributions can generally be made without reducing the Section 199A deduction.

Example 5: Eleanor is the owner of a non-SSTB sole proprietorship with $130,000 in net self-employment income. She has no other income and this year is able to deduct $20,000 in mortgage interest and $10,000 in state and local taxes. As a result, her taxable income is $130,000 (total income from the business) − $30,000 (combined itemized deductions) = $100,000.

Before making any contributions to her solo 401(k) plan, Eleanor has $130,000 in QBI and $100,000 in taxable income. Since the Section 199A deduction is calculated as 20% of the lower of these two numbers, her deduction is 20% × $100,000 = $20,000.

If Eleanor makes a Roth employer contribution, she can contribute up to 20% of her net self-employment income, or 20% × $130,000 = $26,000. Roth employer contributions are reported as deductible contributions followed by a Roth conversion, so Eleanor's QBI is reduced by the amount of the deductible contribution (without being increased by the subsequent Roth conversion). Her QBI after the contribution is $130,000 − $26,000 = $104,000.

However, the Roth employer contribution has no effect on Eleanor's taxable income, which remains at $100,000. And because her taxable income is still the lower of the two numbers even after the Roth employer contribution, her Section 199A deduction remains 20% × $100,000 = $20,000. In other words, there's no difference in Eleanor's Section 199A deduction before or after the Roth employer contribution, because the difference between her QBI and her taxable income before the contribution was more than the amount of the contribution itself.

It's worth pointing out, however, that if the Roth employer contribution is large enough to reduce QBI to the extent that it's lower than taxable income, the contribution will have a negative effect on the business owner's Section 199A deduction.

Example 6: Imagine that Eleanor, from Example 5 above, takes the standard deduction as a single filer ($14,600) rather than itemizing deductions.

In this case, Eleanor's taxable income (before the Section 199A deduction) is $130,000 (total self-employment income from the business) – $14,600 (standard deduction) = $115,400. Since her taxable income of $115,400 is lower than her QBI of $130,000, her Section 199A deduction is 20% × $115,400 = $23,080.

However, as in the previous example, if Eleanor makes the maximum Roth employer contribution of $26,000 to her solo 401(k) plan, her QBI is reduced by the contribution amount, from $130,000 to $104,000. After the contribution, her QBI becomes the lower of the two amounts, and so her Section 199A deduction after the contribution is 20% × $104,000 = $20,800.

Determining whether a business owner's Section 199A deduction will be affected by Roth employer contributions requires a case-by-case process of looking at the type of business the individual owns, the amount of QBI and non-QBI income they earn, other (non-Section 199A) deductions they can claim, and the amounts they plan to contribute to their retirement plan. All of which makes the process complex for business owners and challenging to scale for financial advisors or tax professionals working with them.

In many cases, however, when after-tax contributions with a subsequent Roth conversion are an option, it might be simpler just to choose that route instead. Since after-tax contributions are only limited by the overall contribution limit of 100% of net self-employment income or $69,000 as long as there are no other types of contributions made to the plan, they don't require any other calculations as long as they don't exceed those overall contribution limits!

The main goal of SECURE 2.0 in allowing Roth employer contributions was to provide greater flexibility for employees in deciding how to receive their employers' 401(k) plan contributions. Which makes sense for W-2 employees, for whom employer contributions represent ‘additional' income that wouldn't otherwise be available. But for self-employed business owners eligible for the Section 199A deduction, the IRS's reporting rules create an unintended consequence of increasing the business owner's taxable income, which makes Roth employer contributions less attractive for this group.

Fortunately, solo 401(k) plans remain extremely flexible retirement savings vehicles for self-employed workers. With the option to allocate contributions among employee elective deferrals, employer contributions, and after-tax contributions (which can be subsequently converted to Roth), plan participants can avoid the negative consequences of making Roth employer contributions. Business owners who understand the downsides of Roth employer contributions can set themselves up with solo 401(k) plan providers that allow after-tax contributions and Roth conversions, and can thereby maximize their Roth retirement savings without jeopardizing their Section 199A deduction!