Executive Summary

Many financial advisors who launch solo advisory firms do so with the intention of adding more employees once the firm becomes big enough to support them. And while conceptually it makes sense that the firm will be ready to hire its first employee at some point, in practice, there often isn't a lot of clarity about the right time to actually make an initial hire.

In this post, Kitces Senior Financial Planning Nerd Ben Henry-Moreland offers a framework that solo advisory firm owners can use to decide when their firm will be ready to make an initial hire, based on data from Kitces Research on Advisor Productivity and Advisor Wellbeing as well as industry benchmarking studies on advisor capacity.

There are 2 points in a firm's growth journey that can help solo advisors decide when to make their first hire. One is the advisor's 'capacity wall', which is the point where the advisor has reached their maximum client workload and needs to hire support in order to grow the firm further. Industry benchmarking data suggests that many advisors reach this wall somewhere between 30–40 clients, or $220,000–$320,000 in revenue. And while advisors will sometimes use their capacity wall as a guideline for when to hire, waiting until the advisor is near (or already at) their capacity – and therefore has limited time outside of their existing duties of serving clients and running the firm – to go through the process of searching for, hiring, and onboarding a new employee – can make hiring pretty painful, at least in the short term.

So on one hand, it usually makes more sense for solo advisors to hire well before they reach their capacity, but on the other hand, hiring too early (and before the firm has enough revenue to support the expense of a full- or even part-time employee) can cause a financial strain on the firm and the owner/advisor, whose take-home income is directly impacted by the decision to hire. This brings up the other key point in the firm's growth journey, which is the 'profitability wall': the amount of revenue a firm needs to earn to be able to hire an employee while still adequately compensating the owner/advisor. This amount varies based on the firm owner's goals, but a rough yardstick can be the amount the advisor would earn if they were working as an employee at another firm. Adding this number to the cost of compensating the new employee (including salary plus payroll tax and benefits), plus the firm's other overhead expenses, gives the firm's profitability wall and an estimate of the point in the firm's growth where it can make an initial hire.

Putting these 2 points – the profitability and capacity walls – together gives an estimate of the advisory firm's 'hiring zone', which firm owners can calculate to find the range (in dollars of revenue) where it makes sense to hire a first employee. Furthermore, it can also help firm owners decide whether it even makes sense to hire to begin with, because a firm's profitability wall that is too close to, or higher than, its capacity wall (meaning that the firm owner 'needs' to make a hire before their firm even has the financial ability to do so) can indicate that the firm owner should instead focus on boosting their capacity – either by streamlining their processes or increasing their fees – before focusing on hiring outside help.

The key point, in the end, is that while each firm owner has their own individual roadmap to hiring, they will inevitably need to navigate between the profitability wall and the capacity wall in order to make a smooth transition from a solo firm to one with 1 (or more) employees. And rather than guessing when the right moment to hire will arrive, taking some time to run the numbers in advance can help advisors plan out the hiring process that will work best for them – which should make both the advisor and the new employee happier in the long run!

A lot of advisory firms start out with a sole owner handling all the different functions of keeping the firm running: advising clients, managing investments, bringing in new business, and any number of other administrative tasks that come with operating an advisory firm. But as a firm adds clients, the demands of client-facing work increase, leaving less and less time for the owner to handle the other (but still vital) components of running the business. If the firm grows big enough, it inevitably reaches a point where the amount of work exceeds the number of hours the sole practitioner has available to do it.

With no one else to help shoulder the burden, the advisor has a choice to either scale back growth and remain as a solo practice or hire additional staff to share the workload of keeping the firm running to allow it to grow further.

For some firm owners, staying solo is the end goal: to have complete independence and control over how the firm operates, as well as to take home 100% of the firm's profits. Many mature firms operate successfully as solo practices, with the advisor/owner automating and outsourcing manual tasks as needed to create the time they need for building and maintaining client relationships.

Other solo practitioners find more appeal in hiring additional staff to support the firm's continued growth. In some cases, the owner might plan to grow the firm into a large enterprise with many employees, making the hiring of employees an intentional (and inevitable) step in a long-term business strategy. But not all advisors who hire do so to build a large advisory business; instead, they may see hiring as a way to spend more time on client work and delegate the tasks that they'd rather not do, while still doing most or all of the firm's advisory work and controlling its overall direction.

But for a solo advisor looking to hire their first employee (or employees), there's no obvious way to know when and whom to hire. In many cases, advisors wait to hire until they feel that they're close to reaching their full capacity as a solo advisor – however, waiting until that point usually means that there won't be much time to devote to the process of hiring and onboarding a new employee, making the situation even worse for an advisor who is already feeling the time crunch of reaching their capacity limits.

At the same time, hiring internal staff represents a significant outlay of resources for the firm – not just salary and bonus compensation, but also payroll tax, retirement plan contributions, health insurance, and other benefits the firm owner must offer in order to attract the right talent for the position (not to mention the expenses of additional third-party vendors like payroll and benefits administrators needed to set up and manage these functions). Which means the firm needs to have enough stable revenue to pay 1 or more employees while also having enough profits left over to adequately compensate the owner/advisor.

Having a way to plan out the process of hiring an employee in advance can help avoid the issues of waiting to hire until the advisor is already in a capacity crunch, or hiring before the firm is financially healthy enough to do so. Fortunately, there is data that can help advisors figure out when these points occur for most firms, which they can then compare with their own firms. Drawing on data from industry benchmarking studies as well as Kitces Research on Advisor Wellbeing (2021) and Advisor Productivity (2022), it's possible to create a hiring roadmap for solo advisors who want to take the next step into building an ensemble practice.

The Capacity Wall – When A Firm Needs To Hire

In an ideal world, every potential employer would have a red light installed on their desk that started flashing every time they needed to hire a new employee. But the real world is a lot messier, and it's not always obvious when it's time to hire staff (and when it is obvious, it often means the existing staff is already swamped with work, which would make it even more painful – at least temporarily – to add on the additional burden of hiring and training a new employee). An important consideration in planning to grow beyond a solo advisory firm is the owner/advisor's 'capacity wall', i.e., the point where the firm gets too big for 1 person to manage entirely on their own.

Traditionally, solo advisors have gone mostly by feel in deciding whether they're close enough to their capacity limits to hire staff. Which makes sense on one level: Of the many factors that contribute to an advisor's capacity level (such as the amount of time it takes to serve each client and the number of hours the advisor wants to work each week), most are highly individual to each advisor, which makes it difficult to come up with a one-size-fits-all number to aim for.

The problem with simply going by feel, however, is that by the time the advisor starts to feel crunched as they near their capacity, it may be too late to solve the problem by hiring. Bringing on a new employee requires creating a job posting, interviewing candidates, negotiating employment terms, and onboarding the new employee – all of which, as a solo RIA, the firm likely doesn't have existing processes for. Which means that, at least in the short term, waiting to hire an employee until the advisor already feels near their capacity limits will more likely than not create an even worse time crunch for the advisor until they can bring the new hire fully up to speed.

What Industry Benchmarking Studies Tell Us About Advisor Capacity

Another approach to finding an advisor's capacity wall is to use industry benchmarking data – because although individual advisors each have their own capacity levels, looking at the average across many advisors can give solo advisors at least a general sense of where their capacity limits might lie, so they can plan to hire support staff before reaching that point.

There are 2 numbers that are commonly found in benchmarking studies that can serve as a proxy for a solo advisor's capacity: the number of clients per staff member and the amount of revenue earned per staff member.

Clients per staff member, as its name suggests, is the total number of clients the firm serves divided by the total number of employees at the firm (including owner/advisors as well as support staff). Assuming that most firms generally operate at or near full capacity, clients per staff member suggests the number of clients that each employee at the firm can support.

Revenue per staff member, on the other hand, is the total dollar amount of revenue earned by the firm divided by the total number of employees. In other words, it expresses staff capacity in terms of dollars of revenue earned.

Both clients per staff and revenue per staff are worth considering because not all clients require the same amount of work. For example, some advisors may exclusively serve high-net-worth clients with complex tax and estate planning needs who require a lot of time to serve, which means they could have lower-than-average capacity in terms of clients per staff – but those advisors may also charge higher fees commensurate with the high-value planning they provide, which results in average or above-average capacity in terms of revenue per staff member. So even though clients are easy to count and might make more intuitive sense for determining advisor capacity, revenue per staff can provide a better sense of the actual amount of work being done.

Nerd Note:

Why use clients and revenue per staff, and not per advisor (as is also commonly available in benchmarking surveys) for determining a solo advisor's capacity? Because solo advisors generally serve multiple roles – advisor, client service associate, marketing, administrative, etc. – wrapped up in 1 employee. Using per-advisor metrics compares solo advisors who wear many hats against ensemble advisors with support staff who can devote more of their time to client work. Per-staff metrics capture all of the roles that go into supporting advisory work, making them the fairer comparison for solo advisor capacity.

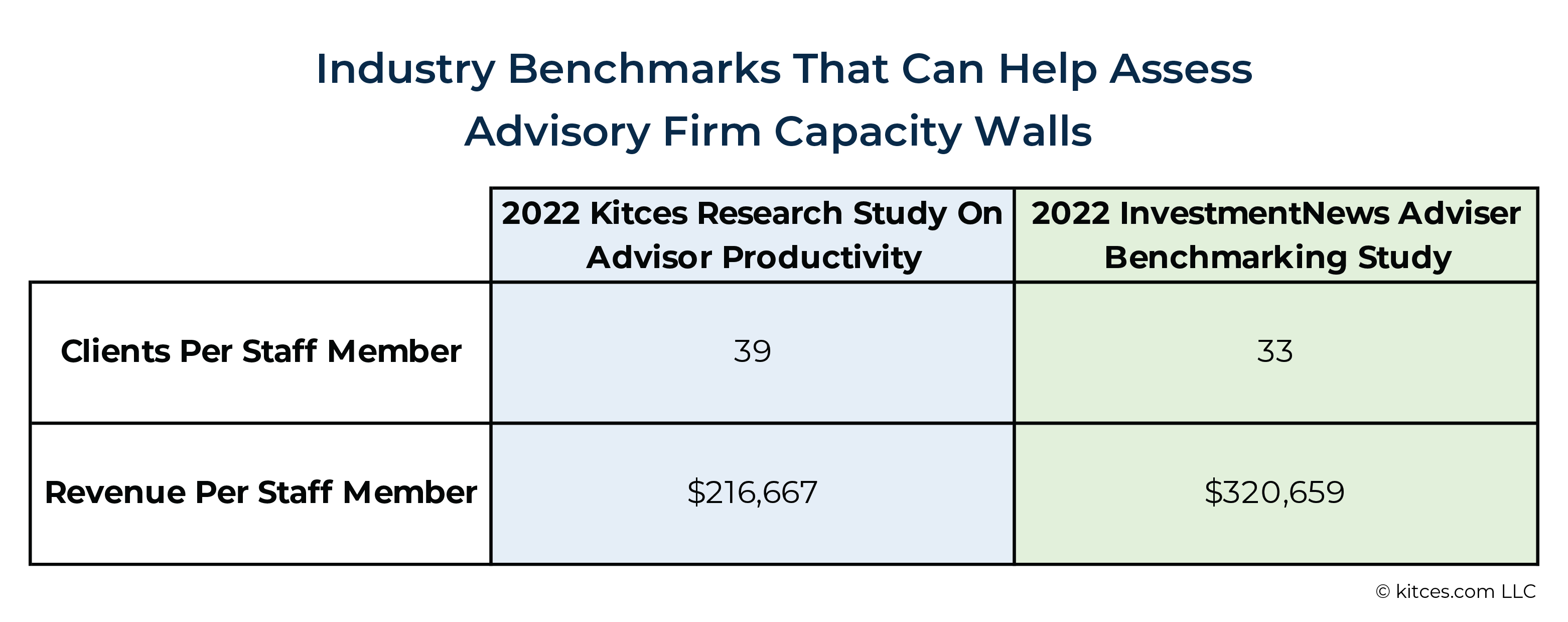

Previously-unpublished data from the 2022 Kitces Research study on Advisor Productivity indicated that the median advisory firm had 39 clients per staff member and $216,667 of revenue per staff member. Another survey, the 2022 InvestmentNews Adviser Benchmarking Study, showed a median of 33 clients per staff member and $320,659 in revenue per staff member in 2021 (perhaps reflecting that the survey's participants were skewed towards larger firms with more staff members and higher-paying clients). In other words, we have a range of typical staff capacity that runs from 30 to 40 clients, or $220,000-$320,000 in revenue, with smaller firms like solo RIAs likely on the higher end of the range in clients and on the lower end in revenue.

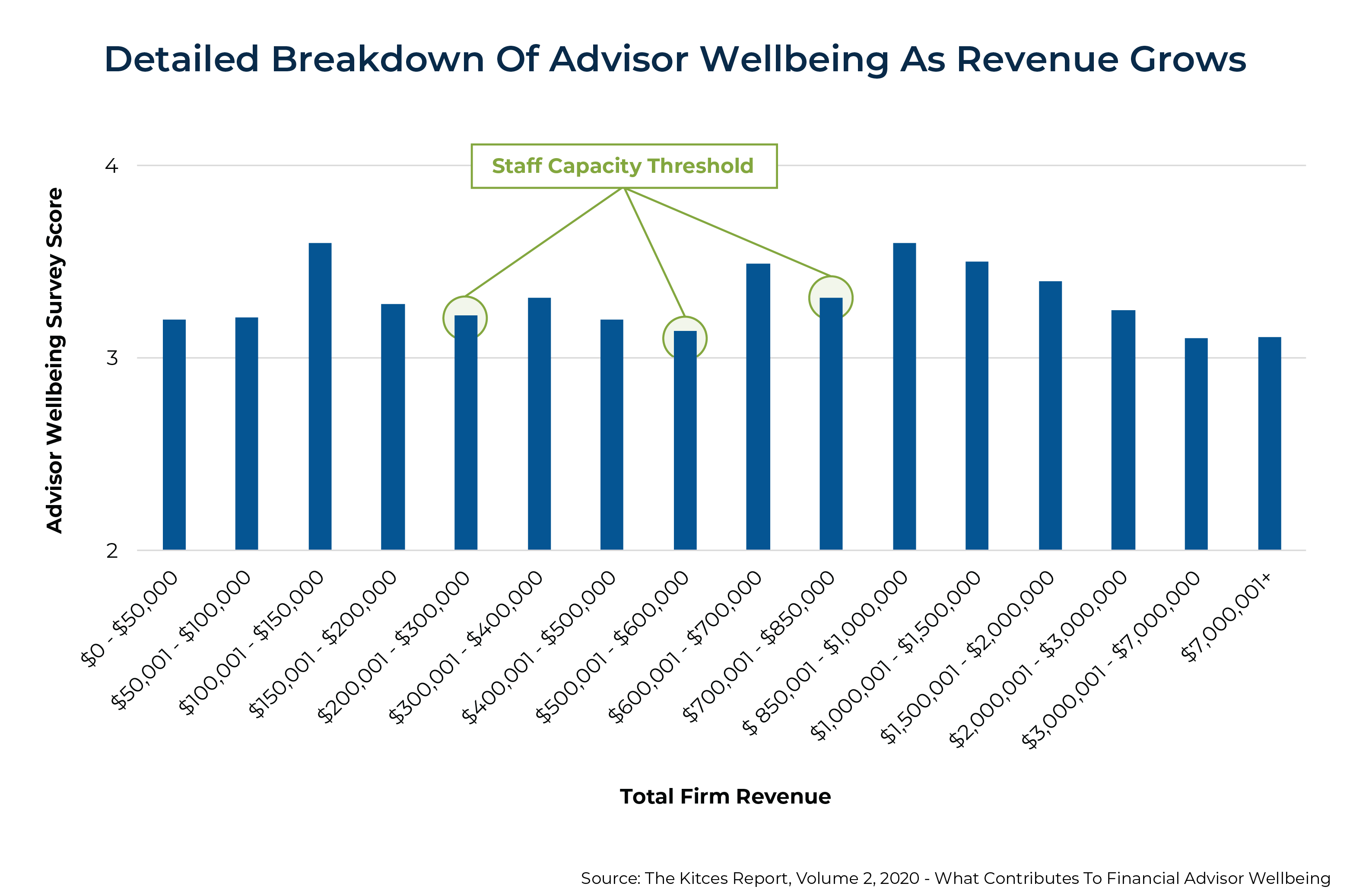

But wait, there's more data! Previous Kitces Research on wellbeing showed that advisors reported lower scores of wellbeing at multiples of $200,000–$300,000 in total firm revenue (as shown below). One interpretation of the highlighted dips in wellbeing scores is that those revenue levels are the points where nearing staff capacity limits leads to stress, overwork, and decreased job satisfaction – which would further support the idea of a capacity wall in the $200,000–$300,000 revenue range that would necessitate a new hire.

In general, then, the benchmarking data suggests that solo advisors can expect to reach a capacity wall by the time they reach around 30–40 clients, or $200,000–$300,000 in revenue, and that hiring before they reach that point would help keep the owner/advisor's workload within a manageable level – and subsequently make the hiring process itself less stressful since it would happen while the advisor has the time to hire and onboard an employee rather than waiting until they're already pushing their capacity limits.

If a solo advisor shouldn't wait until they reach their capacity to hire, then when should they hire? The capacity wall makes for an effective upper limit for figuring out where in a firm's growth journey a solo advisor would need to hire staff to support further growth, but it doesn't fully answer the question of when is the best time to hire.

The Profitability Wall: When A Firm 'Can' Hire

While the capacity wall represents the upper limit of clients and/or revenue at which an advisor would need to hire additional staff, it's also worth remembering that the cost of a new hire can eat up a significant chunk of the profits of the firm owner, meaning there is also a lower limit to keep in mind when considering when to hire.

First, it's helpful to know how much to expect the cost of a new hire will be. The 2022 Kitces Research study on Advisor Productivity found that most firms tend to bring in a Client Service Administrator (CSA) as their first hire. And per the 2022 InvestmentNews Adviser Benchmarking Study, the median CSA earns about $58,500 per year in combined base salary and incentive pay. But that in itself doesn't represent the whole cost of the employee to the firm. When adding payroll tax (7.65% of gross pay up to the Social Security wage limit of $160,200 in 2023) and benefits such as health insurance and retirement plan contributions, the actual cost to the firm could end up being an additional 20% or more beyond just the employee's cash compensation – meaning an employee who earns $58,500 could actually cost the firm (at least) $58,500 × 120% = $70,200.

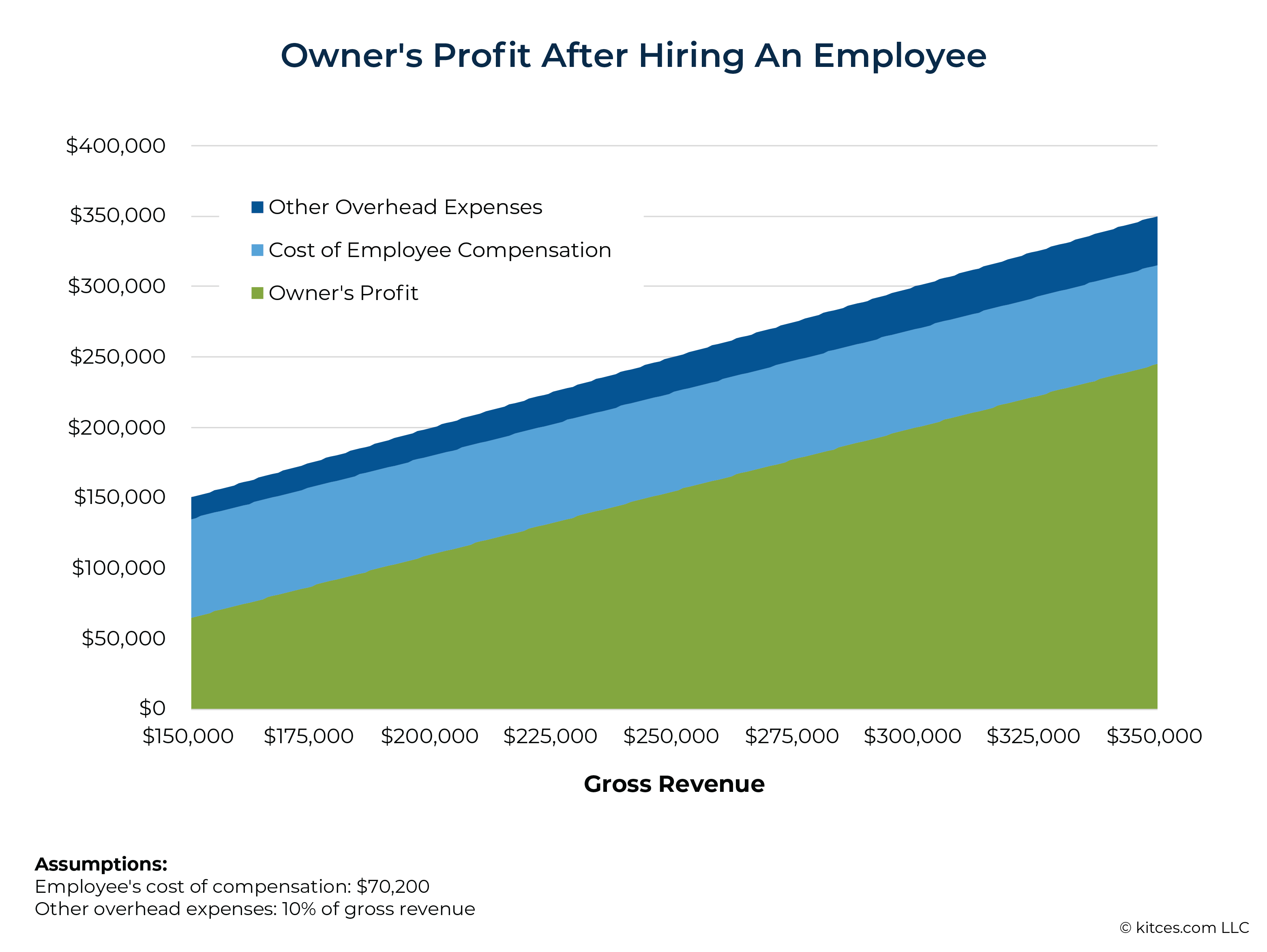

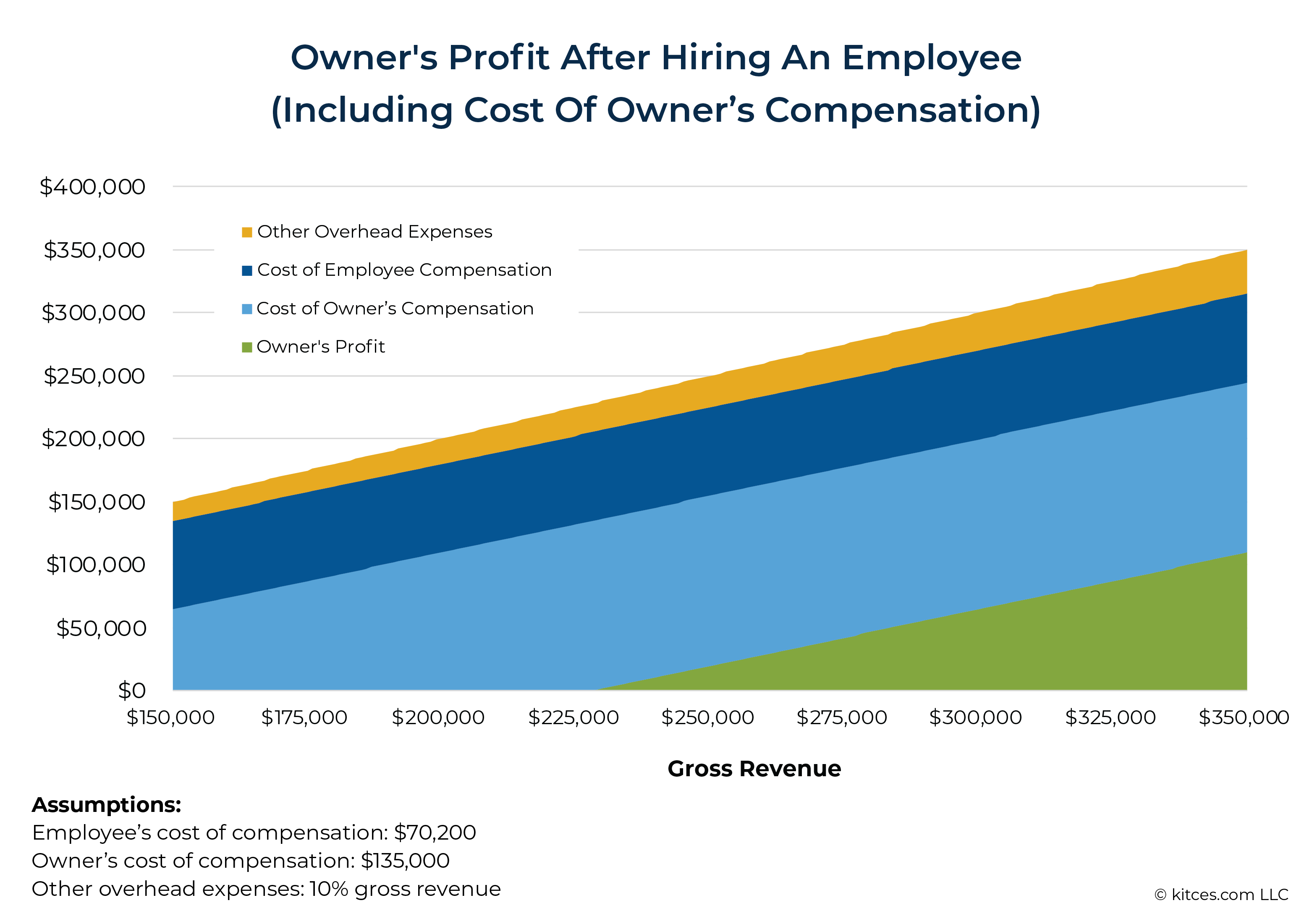

This is no minor expense for a solo advisory practice just nearing its first capacity threshold. For a firm with 'just' $150,000–$350,000 in annual revenue (i.e., the range between where they start to consider hiring up through where they have likely already made a first hire), hiring a CSA at a cost of $70,200 represents between 20% and 47% of the firm's gross revenue. Adding on the firm's other overhead costs for technology, office expenses, insurance, etc. (which often tend to run between 10%–20% for solo advisory firms), the first hire could reduce the owner's take-home profits to less than half of the firm's revenue. Or, in dollar terms, as shown below, the owner of a firm with $150,000 in revenue would see their take-home income drop from $135,000 before the hire to less than $65,000 afterward if they hired the 'median' CSA.

The cost of hiring an employee means that when deciding when to hire for the first time, one of the key considerations for firm owners is how much of a cut to their bottom line they're willing to take. If the firm owner's take-home income after hiring an employee – after subtracting the cost of the employee plus other overhead expenses – would be less than they are willing to make as compensation for owning (and working for) an advisory firm, then they would need to focus on boosting revenue and/or reducing overhead costs before hiring (or be willing to live with less take-home pay until they can grow the firm's revenue enough to make up the difference).

In contrast to the 'capacity wall', which represents the upper limit of when a solo advisory firm would want to hire, the 'profitability wall' – i.e., the firm size that would result in the lowest amount of take-home income after the hire that the owner/advisor would be willing to accept – represents the lower limit for hiring.

Different owners will naturally have different opinions on acceptable levels of take-home income after hiring an employee, but one thing to consider is that practicing advisory firm owners serve their firms in 2 capacities: as an advisor working for the firm, and as an owner of the firm. To capture both of these roles, advisory firms sometimes structure their income and expense statements to include the cost of the owner's compensation as an advisor listed as an expense (with the amount being based on what the firm would need to pay to hire a different advisor to do the same work), so that the firm's bottom-line profits reflect 'just' the profitability of owning the firm.

By the same token, advisory firm owners can think of their profitability wall as the level of firm revenue resulting in the minimum amount of take-home income that would pay them adequately as an advisor, with any additional income accruing to them as the owner of the firm.

For example, according to the 2022 InvestmentNews Adviser Benchmarking Study, the median 'Lead' advisor earned just under $135,000 in base pay in 2021. Using that number as a yardstick, a firm would need to have at least that much income after subtracting overhead expenses and the cost of the new employee in order to be 'profitable' in the sense that there would be any net profits left over after adequately compensating the owner/advisor for their advisory work.

As shown below, using $70,200 as the cost of a CSA and 10% of gross revenue for other overhead expenses, a firm would need to have over $225,000 in gross revenue just to compensate the owner at the same level as the 'median' lead advisor. That revenue level of $225,000 represents the firm's profitability wall. Hiring before reaching that level, as seen below, would reduce the advisor/owner's take-home income to the extent that they would be underpaid compared to the typical advisor and not paid at all as a firm owner.

The profitability wall of any advisory firm – i.e., the minimum revenue level where it would make sense to hire a new employee – can be calculated as the sum of 4 components: (1) the total cost of hiring the employee; (2) the amount of the firm's other overhead expenses; (3) the cost of adequately compensating the owner/advisor for their work for the firm; and (4) the minimum amount of additional profit required by the owner.

Finding The 'Hiring Zone' Between Capacity And Profitability

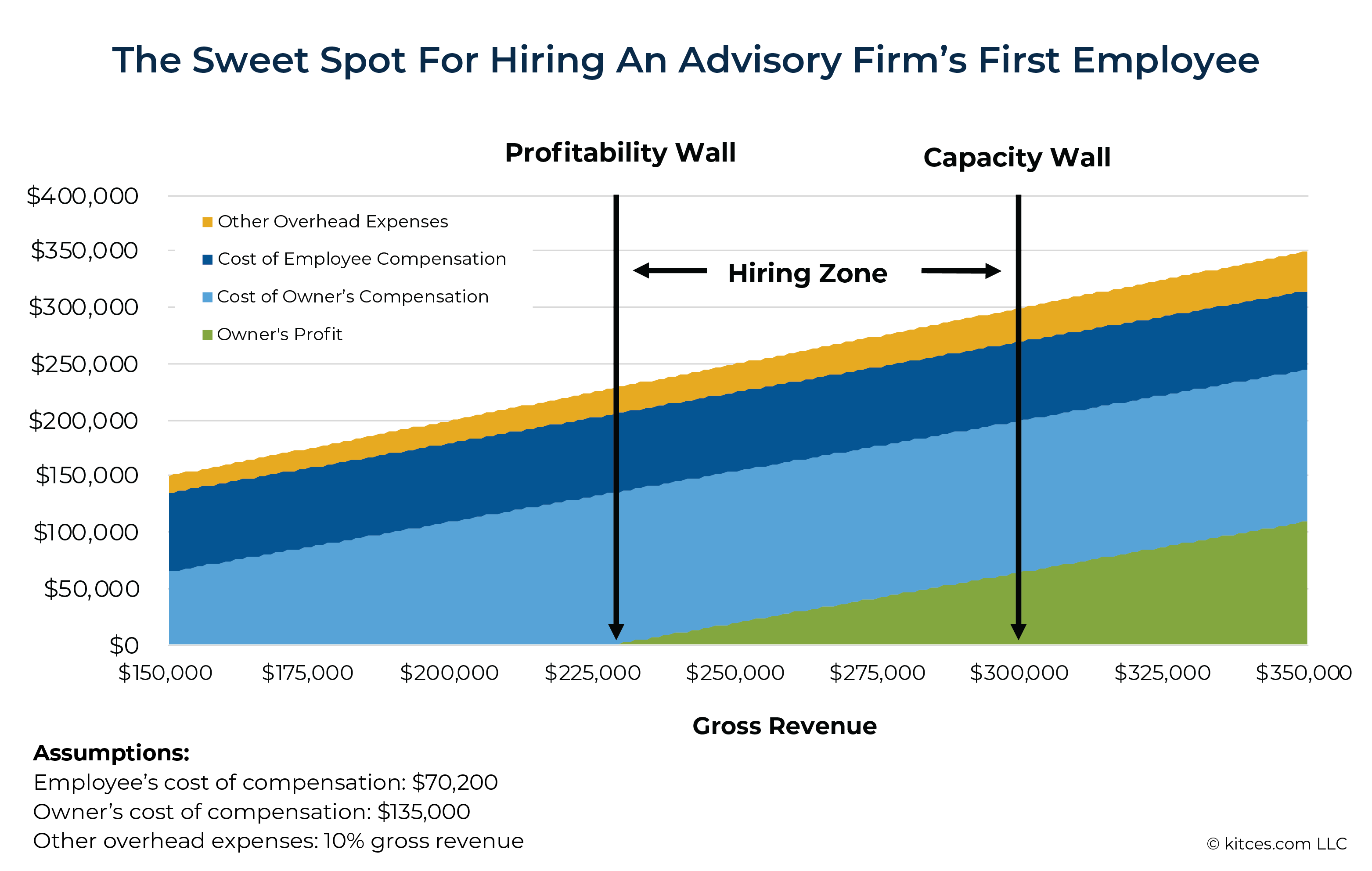

If an advisory firm's capacity wall represents the point at which it needs to hire an employee to support further growth, and the profitability wall is the point where it is financially stable enough that it can hire a new employee while still paying the owner/advisor an adequate income, the area in between the 2 is the 'hiring zone' – i.e., the sweet spot where the firm is profitable enough to hire and retain an additional employee, but hasn't grown so much as to overwhelm the owner/advisor's ability to serve their clients.

The graphic below is an example of where a hypothetical firm's hiring zone would lie, again using $70,200 as the cost of the new hire, $135,000 as the owner/advisor's minimum take-home pay, and 10% of gross revenue as the amount of other overhead costs. If the firm's owner wanted to realize at least $135,000 in take-home income after hiring a new employee, the firm would need to have about $225,000 in gross revenue, representing the lower (profitability) wall. Hiring below that level would result in less take-home income for the advisor than they need or want.

On the other end, if the advisor had a capacity of 30 clients as a solo advisor, with each paying $10,000 per year in fees, the firm's upper (capacity) wall would be $10,000 × 30 = $300,000 in revenue. Waiting to hire until after reaching that level would leave the advisor stretched for time to the extent that they couldn't continue to grow the firm without putting excess strain on their time and energy.

Ultimately, then, the firm's hiring zone – and when the owner/advisor would want to aim for getting through the process of hiring and onboarding a new employee – is between $225,000 and $300,000 of gross revenue.

The numbers above (based on industry averages) present a fairly wide range of revenue levels for the firm owner/advisor to map out when to hire an employee. However, an advisor with a lower capacity wall, or a higher profitability wall, would have a narrower hiring zone, which could mean that they would be better off considering changes that would improve those numbers – thereby creating a wider hiring zone – before moving forward with hiring.

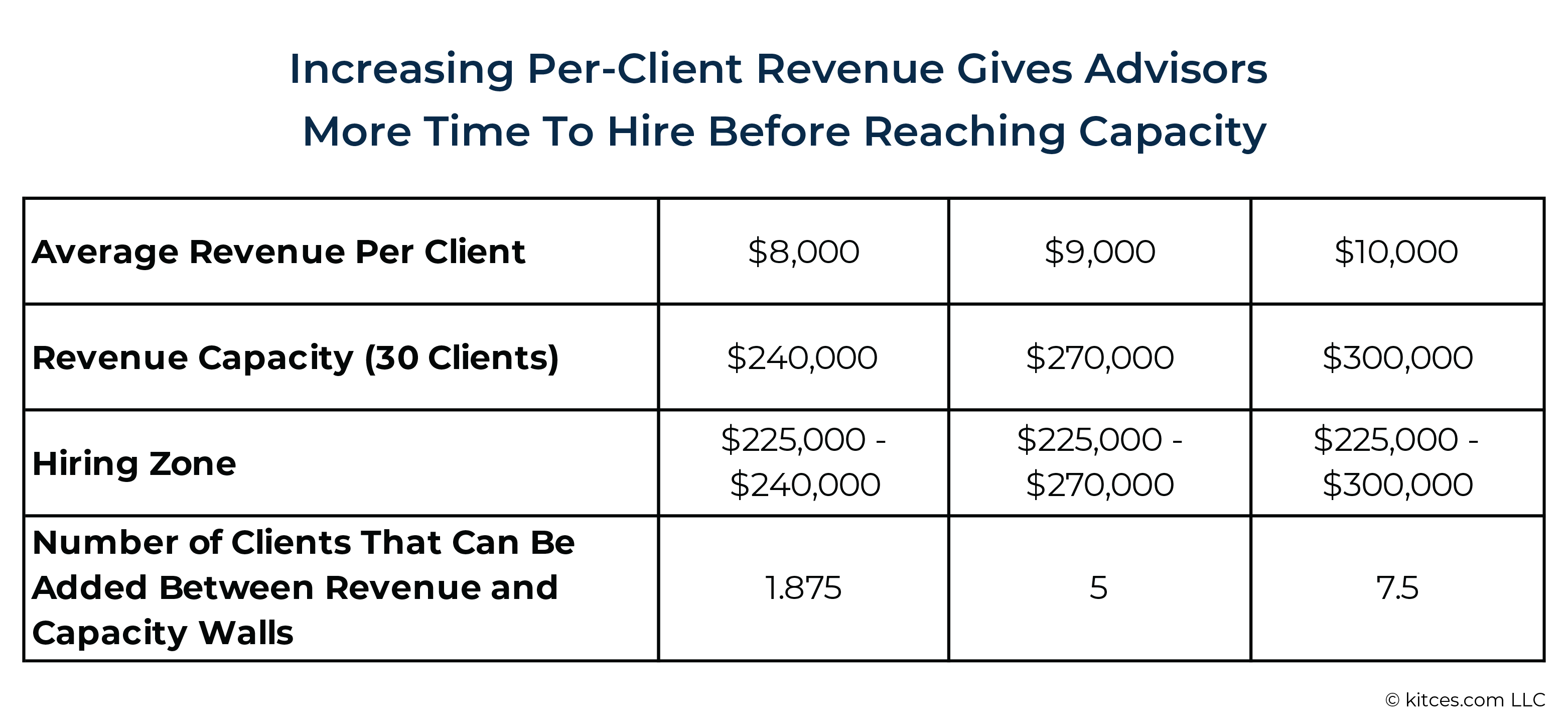

What the width of the hiring zone represents is the amount of growth that is possible between when a firm can make its first hire (i.e., the profitability wall) and when it hits the solo advisor's capacity so that it needs to make a hire (i.e., the capacity wall). For the firm in the example above, with a hiring zone between $225,000 and $300,000 of total revenue, the firm owner can go through the process of selecting and hiring an employee in the time it takes to add 7–8 new clients at $10,000 of revenue each.

However, imagine that the firm in the example above had an average of $9,000 of revenue per client instead of $10,000. If they still only had the capacity to serve 30 clients, then their capacity wall in revenue terms would be $9,000 × 30 = $270,000, leaving a hiring zone of $270,000 − $225,000 = $45,000 and meaning they could only add 5 new clients between crossing the profitability wall and reaching the capacity wall. And if their average client revenue was $8,000, their capacity wall would be at $8,000 × 30 = $240,000, which means their hiring zone would be only $240,000 − $225,000 = $15,000, leaving them with only 1–2 clients' worth of growth until reaching the advisor's capacity.

In other words, the higher the advisor's per-client revenue, the more time the advisor will have to make a hire in between the time when it becomes financially possible to do so and the time that hiring becomes necessary from a capacity standpoint.

Conversely, the downside of a narrow hiring zone is that once the solo advisor reaches enough revenue to be able to hire, they would have an almost immediate need to find, hire, and onboard an employee to avoid going over their capacity limits. In some cases, a solo advisor could reach their capacity limits before ever becoming profitable enough to hire an employee – which is why it's important for advisors to figure out their own capacity wall to determine whether their problem can really be solved by hiring support staff, or if doing so would simply add financial strain to a practice already struggling with the limits on the owner/advisor's time capacity.

In those cases, the more urgent need for the advisor is likely to focus on increasing their capacity either by increasing their efficiency in serving clients (and being able to serve more clients while charging the same fee) or increasing their fees (and decreasing the number of clients it takes to become profitable enough to hire an employee). An advisor who reaches their capacity wall despite not having overcome their profitability wall is likely to have problems that hiring an employee won't solve (and may very well make worse), making it a better idea to focus on streamlining services and/or adjusting fees as a solo advisor before looking to grow the team further.

Solo advisory firms, by definition, start with individuals, and individuals have their own ideas, goals, and needs in running a business, meaning that the road map for making an initial hire looks different for every single practice owner.

However, there are 3 steps that any solo advisor can take to map out the process of hiring for their own firms:

- Determine the 'capacity wall' by identifying the number of clients – and revenue level – at which the firm would need to hire an employee to keep the advisor within their capacity, which benchmarking data suggests is between 30–40 clients and $200,000–$300,000 in revenue, but could vary based on the time it takes the advisor to serve each client and the fees paid by each client.

- Determine the 'profitability wall' by identifying the revenue level at which the firm can hire an employee by adding the cost of the employee, the firm's other overhead expenses, and the amount of income the advisor needs to be able to take home to make the hire worthwhile.

- Compare the results of steps 1 and 2. If the resulting 'hiring zone' between the capacity wall and profitability wall is wide enough that the firm can search for, hire, and onboard an employee while staying comfortably under the advisor's capacity, that's great – but if the range is too narrow, then the advisor may need to focus on streamlining their processes and improving their profitability to create a stable enough foundation for their firm to make hiring sustainable.

Ultimately, going through these steps beforehand can help smooth the process of bringing on a new employee by ensuring that it's done while the advisor still has the capacity to spare (or, at the very least, making it clear whether it's a better idea to hire or focus on increasing capacity in other ways). Either way, the end result should be the ability to serve clients better and more efficiently, and for the advisor, a sense of higher wellbeing while staying on their preferred growth journey!

Leave a Reply