Executive Summary

The use of Roth IRAs is increasingly popular as a tax planning strategy, especially in the years since 2010 when the income limits on Roth conversions were lifted, opening up access to Roth conversions for anyone. And although the income limits from conversions has been eliminated, the ability to recharacterize a Roth conversion remains, no longer as a mere "undo" for an accidental conversion at high income levels, but now increasingly as a proactive strategy to convert and wait and see what happens with the investment; if it's up the conversion stays, and if it's down it's recharacterized to be converted again in the future (at a lower tax cost).

However, one significant caveat of Roth recharacterizations and this kind of wait-and-see-before-deciding strategy is that Roth recharacterizations must allocate gains/losses across the account on a pro-rata basis. As a result, one cannot simply "cherry pick" the worst performing investments from a Roth conversion to subsequently recharacterize, and trying to do so can accidentally shift originally-Roth investments into a traditional IRA in the process! Fortunately, though, a special rule allows Roth recharacterizations to occur on a standalone basis, as long as the conversion is placed in a separate account in the first place.

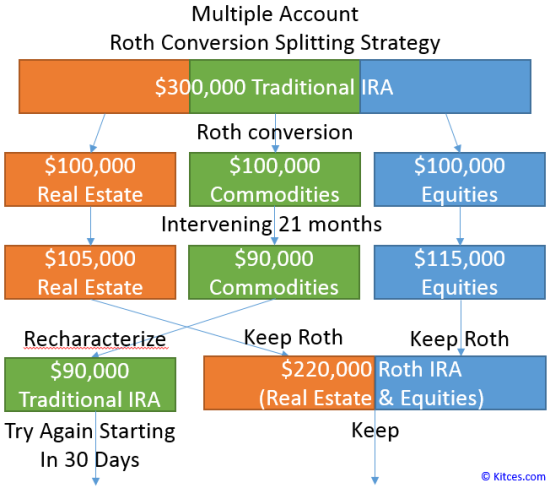

In fact, this "separate account" rule is so favorable, for larger Roth conversions it becomes another proactive planning strategy unto itself - instead of merely converting into a single standalone Roth IRA (separate from existing Roth IRAs), complete the Roth conversion one investment/asset class at a time into a series of separate standalone Roth IRAs (separate from any existing Roth IRA and each other). By doing so, the investor can actually see the outcome of each individual Roth investment, one at a time, keeping the top performer(s) and recharacterizing the rest, with as much as a 21-month time window to see the investment results before being forced to make a final decision! While ultimately the outcome of whether a Roth conversion is a good deal or not is still driven by tax rates, being able to know the investment results, and cherry pick the top performer after the results are in, can go far in turbocharging the value of an already-beneficial Roth conversion!

Technical Rules For Roth Conversions And Recharacterizations

When Roth IRAs – and the ability to convert to them – were originally established, taxpayers had to have no more than $100,000 in Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) in order to convert. Since the beginning of 2010, though, anyone has been permitted to complete a Roth conversion, regardless of income. When a conversion occurs, any amounts from the original IRA that would be taxable do in fact become taxable, though no early withdrawal penalty will apply (and as long as the funds in the conversion are subsequently held for at least 5 years, that conversion amount permanently avoids the early withdrawal penalty).

In the early years, taxpayers would sometimes find that they needed to undo a Roth conversion, because it turned out at the end of the year they were over the income limits. With the income limits gone, it still remains the case that sometimes taxpayers wish to undo a Roth conversion, such as when income turns out to be higher than expected and simply results in a higher tax rate than anticipated and desired for the Roth conversion. In other cases, there is a desire to undo a Roth conversion because the investment falls significantly in value after the conversion, and the taxpayer would like a chance to convert it again at the lower value.

Fortunately, to accommodate these scenarios, the Roth rules do allow an “undo” in the form of a Roth recharacterization. The recharacterization rules are relatively straightforward - the deadline to recharacterize is October 15 of the following year (always October 15, regardless of whether an extension was filed or not), and the converted funds simply have to be transferred from the Roth back to a traditional IRA (along with any associated gains/losses). Once the recharacterization is complete, it’s as though the conversion never happened, and there are no income tax consequences at all (not for the recharacterization itself, nor for the original conversion). Notably, if a recharacterization happens, the taxpayer cannot do a new conversion until the later of: 30 days after the recharacterization, or; the year following the year of the conversion.

Example 1a. Charlie completed a Roth conversion in February, and decided to recharacterize it in November of the same year when he realized his income was going to be so high it wouldn’t be desirable to keep the conversion. As a result, Charlie recharacterizes his conversion. Given the recharacterization, Charlie will not be permitted to do another conversion again until next year.

Example 1b. If Charlie had waited to recharacterize until after the end of the year – for instance, he recharacterized next April 10th (which is still well in advance of the deadline next October 15) as he was finishing his tax return – he would not be permitted to do another Roth conversion until May 10th (30 days later).

Allocating Gains/Losses And The Multiple Account Splitting Rule For Roth Recharacterizations

When an entire Roth IRA that was converted is subsequently recharacterized, the process is relatively straightforward: the entire Roth IRA is transferred back to a traditional IRA, since it will implicitly include any gains/losses that occurred during the temporary conversion period by virtue of the fact that it’s the entire account. However, when the original conversion was only a portion of the total account – i.e., the Roth conversion was added to an existing account – the rules under Treasury Regulation 1.408A-5 Q&A-2(c)(1) stipulate that the recharacterization must include a pro-rata share of the gains/losses on the entire account.

Example 2a. Jeremy converted $50,000 of XYZ stock from his traditional IRA into his Roth IRA, adding it to an existing $200,000 Roth IRA account balance that’s invested in a broad range of assets (bringing the total up to $250,000). Early next year, Jeremy realizes that the $50,000 of XYZ stock has declined 30% (to $35,000), while the rest of the account is up 20% (to $240,000). As a result, Jeremy would like to recharacterize the XYZ stock conversion, since it triggered $50,000 of income tax consequences but is now only worth $35,000. However, he cannot just recharacterize the stock; instead, he must recharacterize a pro-rata share of the entire account. As a result, if Jeremy wishes to recharacterize, he would be required to recharacterize $55,000 (since the total account balance started at $250,000 and is now $275,000, so in the aggregate it is up 10%), which means he would have to put back all of the XYZ stock and another $20,000 of investments that were originally in the Roth IRA in the first place! Realizing how disadvantageous this would be, Jeremy decides not to do so!

Fortunately, there is a way to avoid the unfavorable result of the preceding example. Under Treasury Regulation 1.408A-5, Q&A-2(c)(4), the pro-rata recharacterization rule only applies to the actual IRA containing the particular contribution to be recharacterized. As a result, if a Roth conversion occurs to a standalone account, only that account – and the associated gains/losses – must be considered when completing a recharacterization.

Example 2b. Continuing the prior example, if Jeremy had converted the $50,000 of XYZ stock to a standalone second Roth IRA (instead of mixing the money in with the first Roth IRA), then Jeremy would only need to recharacterize $35,000 (the actual value of the entire second Roth IRA containing XYZ stock) to avoid the tax consequences of the original conversion, instead of being forced to recharacterize $55,000. This would allow Jeremy to enjoy the benefits of recharacterization (avoiding $50,000 of conversion income on stock now only worth $35,000) without being forced to shift additional Roth IRA assets back to a traditional IRA just to do so (as occurred in the earlier pro-rata rule example).

In fact, given how much more favorable and flexible it is to recharacterize a particular investment that has gone down in value after a Roth conversion, it is arguably a standard best practice to always do new conversions to a standalone Roth IRA if there is any chance that there could be a material decline that would trigger a desire to recharacterize. At worst, the second Roth IRA can always be merged back in with the first for simplicity after the time window has passed for recharacterization and it’s certain the account will remain in place.

Diversifying Roth Conversion Asset Classes Across Multiple Accounts For Potential Recharacterization

While the original purpose of the “separate account” rule for recharacterizations was likely just to isolate a new Roth conversion from existing Roth assets – per the preceding example – the rules also allow for a more proactive Roth conversion strategy involving larger conversions that include multiple investments or whole asset classes.

Example 3. Harold plans to convert $300,000 worth of various investments in his traditional IRA, which is comprised (equally) of real estate, commodities, and equities. Rather than transfer the $300,000 conversion on top of an existing Roth IRA, or “just” into a standalone $300,000 Roth IRA, Harold can instead create three new $100,000 Roth IRAs, one for the real estate, the second for the commodities, and the last for the equities. If Harold completes these conversions at the beginning of the year in January, he can wait upwards of 21 months (until early October of next year) to decide whether to recharacterize any of them. If after the time interval, the equities are up 15%, the real estate is up 5%, and the commodities are down 10%, Harold can “cherry pick” to keep the converted equities and real estate in place, but recharacterize the now-worth-$90,000 commodities allocation. And because each investment is held individually in its own Roth IRA, Harold does not need to allocate the gains/losses of the other asset classes when determining how much to recharacterize for his commodities!

As this example and the associated graphic illustrates, the essence of the convert-multiple-asset-classes-into-multiple-Roth-IRAs is the opportunity to cherry pick, one asset class/investment at a time, which will be kept as a Roth (because the investment is up) and which will be recharacterized (because the investment is down). This opportunity applies only by converting into multiple accounts; if multiple investments are converted into a single Roth IRA, then all the investments within that account share in the pro-rata rule when determining gains/losses associated with the recharacterization.

Notably, one important caveat of this strategy is that if Harold wants to try again to convert the commodities that were recharacterized, he must wait 30 days, and thus will only have at best 11 months (from November of this year until October 15 of next year) to try again (i.e., because he waited until October of the following year to convert, most of the current year will have passed already). In addition, if the reality was that last year was the one “low income” year that was appealing to convert (e.g., Harold lost his job last year, but is employed again this year with higher other income) it may no longer be appealing to convert again, in which case by recharacterizing the commodities that were down Harold has conceded that they may not be converting at all (or at least, he’ll have to wait for another low income year, however long that may be). In practice, this means that investments only down slightly might be kept as a conversion because the tax timing outweighs the minor investment loss (though with significant enough losses, it will likely still “pay” to recharacterize and try again in the future with the lower account value).

Planning Issues And Opportunities When Splitting Roth Conversions For Partial Recharacterizations

While in theory the multiple account Roth conversion (or really, recharacterization) strategy can be relevant for any asset and account size, from a practical perspective investors may not really want to split accounts until dollars are significant (tens if not hundreds of thousands of dollars), though to each their own about what is “large enough” to be meaningful. Given the relative simplicity, arguably anyone doing a Roth conversion should at least keep the funds separate from any existing Roth IRA funds unless there is no material chance of a decline (e.g., the assets are held in cash or short-term bonds anyway, for some reason).

For those who wish to not just hold Roth conversion assets separate from an existing Roth, but actually split a conversion itself into multiple accounts, it’s obviously crucial that the funds be invested differently in the first place (or become invested differently when the Roth conversions are initially done). If any/all split Roth accounts will hold the same investment position anyway, there’s no reason to split them. Conversely, if there are different investments, ideally they should be substantively different, with a low expected correlation, or there’s a “risk” that their returns will be so similar (all up, or all down) that having separate accounts will be irrelevant anyway.

In many cases, those considering Roth conversions must consider an additional constraint – there may only be “so much” room to do a partial Roth conversion and stay within a current or targeted tax bracket in the first place. As a result, it may be best to deliberately “over-convert” with the intention and expectation up front of recharacterizing whatever has the least favorable performance.

Example 4a. Jenny has determined that she can convert $100,000 this year and still finish within the 25% tax bracket. Jenny converts into two $50,000 Roth IRAs, the first holding equities, and the second holding real estate. At the end of the year, the equities are up 10% and the real estate is down 15%, so Jenny keeps the former and recharacterizes the latter. While Jenny has now ‘successfully’ converted what was up and avoided the conversion on what was down, she finishes the year having only converted $50,000 when her goal to fill her tax bracket was to convert $100,000.

Example 4b. Trying to avoid the outcome of the preceding scenario, Jenny converts $200,000 this year, placing $100,000 each into equities and real estate. Now, when equities finish up 10% and the real estate is down 15%, and Jenny recharacterizes the real estate, she finishes with her full $100,000 conversion allotment (in equities) and has ensured that she only converted investments that went up.

Example 4c. Continuing the prior example, if the returns instead were that equities were up 20% and real estate is up 5%, Jenny might still choose to just keep the equities and recharacterize the real estate. Yes, both asset classes are up, which is favorable, but if Jenny has determined that she does not want to push her income past the 25% tax bracket, she may still wish to recharacterize whichever investment is up the least (in this case, the real estate). Thus, the ultimately goal of the strategy is truly to keep what performs the best and recharacterize what performs the least, not merely to keep what is up and recharacterize only if it’s down.

Notably, this strategy can be carried out repeatedly year after year with a series of ongoing conversions, though as noted earlier subsequent conversions may not have as long of a time window to grow if the conversion can’t happen until the investor knows which investment has been recharacterized in the first place (because of a systematic process of always converting far more than is ‘necessary’ and recharacterizing the excess).

Ultimately, it’s still crucial to remember that the core driver of whether or not a Roth conversion will be effective is a comparison of current and future tax rates. Subsequent growth determines how much wealth is created by a good Roth conversion, but doesn’t determine whether it will be favorable in the first place (as that’s a function of tax rates). As a result, even with favorable growth an investor should only “keep” a Roth conversion that’s done at a favorable tax rate in the first place (in fact if so much is converted that it drives the tax rate too high now, greater growth actually makes the outcome even worse). Nonetheless, the Roth conversion rules, and the multiple account recharacterization strategy, does provide a nice opportunity to convert more than enough and recharacterize whatever performs the least, ensuring that an appropriately sized Roth conversion is done, and that it is done with whatever asset class or investment performs the best, too!

Now the important question. When do you recommend taxes be paid? When the conversion occurs? Before the end of the tax year? By April 15th? Or wait until the extension is filed?

Chicken Little, if you are not unconverting, (and you probably won’t know if you are unconverting until close to 10/15 of the following year) the conversion will be includible in your income and typically tax will be owed on the conversion. An extension to file your return is not an extension to pay the tax.

Taxes are generally due by April 15th of the following year, though you may be subject to estimated tax penalties if you don’t withhold enough or file estimated taxes when due. Generally if you withhold at least 110% of last year’s tax liability (or 90% of the current year tax liability), you should be ok paying by April 15 without filing estimated tax. Otherwise, you may need to file estimated taxes starting in the quarter when the conversion occurs. (See IRS publication 505 to see how much you need to withhold to avoid the estimated tax penalty or check with your tax advisor). Keep in mind that if you convert, pay tax, file your return and then unconvert, you can file an amended return within the required timeframe to get a tax refund. However, if you don’t withhold enough or have estimated taxes paid on-time, you may end up owing penalties and interest. Happy Roth-ing and Good luck!!

You know those that knew this strategy for the last few years liked being in the minority of people who understood it. But sure enough there always has to be some blogger that comes around who feels like they have to release it to the public. Thanks Mike…

Although Slott was probably more responsible.

Semi-kidding

Michael, I have a situation with Vanguard that is outlined in your example 1b. I converted several Rollover IRA’s in early 2013 to separate ROTH Accounts with Vanguard. Many are still in conversion awaiting closer proximity to Oct 15, 2014 and aligning them with my Federal Marginal Tax rates given those specific investment returns for each account. I have waited my 31 days in an attempt to make conversions for 2014 and start the clock for my 2014 return with a new period to Oct 15, 2015. Vanguard will not allow my to convert these accounts in 2014 (so far). I have asked them to perform this operation on at least two occasions with the last conversation – I asked the specialist to also confirm their no can do answer with their management. They have told me more than once their Vanguard software will not allow this and I must wait to convert until after Jan 1, 2015. (Pub 590 is a mess using different naming conventions in places too but ‘echo’ Vanguard tells me their software will not allow a conversion on these accounts.) I would prefer not to transfer these accounts to a different Trustee but I really want this clock restarted to potentially capitalize on the 2014 Marginal Tax Rates as opposed to losing a year. What can I do to convince Vanguard?

net – for these in question I converted in 2013. I recharterized in 1Q 2014 and waited 31 days requesting another conversion. Vanguard will not allow conversion until 2015. (I was successful in getting ETRADE to do this same scenario conversion with a very small account and hope it does not get somehow disallowed in the future.) Thanks for any and all assistance!

I just heard Robert Keebler host a call with the AICPA group and asked this question best I could in approx 50 – 100 characters. Robert says I need to call Vanguard again – they have not interpreted this correctly. I hope it works on the third attempt. Thanks for this forum too.

Michael — Thanks for the excellent post — and the excellent coverage of Roth IRAs generally. I have been thinking about a similar idea where the Roth IRAs have the same investments but are converted at different times in a given year.

Let’s say I plan to retire in 2015 with a large traditional IRA and with enough non-retirement assets to cover expenses for about 5 years. Since I wont have much taxable income in those early years when I’m spending down my non-retirement accounts, It seems reasonable to make small Roth conversions each year to capture the lower tax brackets (e.g., up to 10-15% Federal Tax rates). Let’s assume I can make a yearly Roth conversion of 50K$ with taxes also coming out of my non-retirement assets.

In January 2015 I convert 50K$ from the traditional IRA to a first Roth account (“Roth-2015A”) with the same distribution of assets that I have in the traditional IRA across several mutual funds. By April the portfolio has fallen by 5% and I convert another 50K$ to a second Roth account (“Roth-2015B”). By July the the portfolio has fallen by another 5% and I convert another 50k$ to a third Roth account (“Roth-2015C”). The portfolio starts to rise after that through the rest of the year, so I don’t make any additional Roth conversions.

In January 2016 I restart the process by converting 50K$ to a first Roth for this year (“Roth-2016”). On the next day I re-characterize the first two Roths from 2015 (Roth-2015A, Roth-2105B), and then after 30 days I have the option to continue converting 50K$ amounts to additional Roths for 2016. I also still have the option to re-characterize Roth-2015C by October 15, 2016, if the markets head south. Otherwise, I get something close to optimal for my yearly 50K$ conversion.

This sounds reasonable to me and not inconsistent with what you have proposed.

Rob,

This sounds not only reasonable, but a smart strategy to me as well. Have you drawn a different conclusion in the three years since you wrote this post?

I am planning on doing something very similar beginning in 2018.

Mike

Mike —

Thanks for the compliment. This still sounds like a good plan to me, and I’m surprised I haven’t seen it discussed elsewhere. I haven’t quite pulled the retirement trigger yet myself to try it out. Good Luck!

— Rob

Michael,

I have a quick question

regarding the 5 year holding period rule. At my firm, we are opening

Roth conversion accounts to segregate the

conversions and then transferring the assets of these Roth conduits accounts that performed well

into the existing Roth account. Would the assets be subject to the 5 year

holding rule for this transfer or is the 5 year holding period rule only applies

to the account? (In this case the conduits account)

Ludo,

The 5-year period for penalty-free withdrawals of Roth conversions applies regardless of what account the money ends out in. Each Roth conversion has its own 5-year time period for THAT Roth conversion principal to be withdrawn penalty free.

Withdrawals from a Roth are presumed to come from original contributions first, then from conversion contributions, and then from gains last.

– Michael

When creating multiple Roth conversion accounts for purposes of splitting a conversion into multiple buckets, is it necessary that the Roth Conversion IRA accounts be set up in separate IRA plans from each other? Some brokerages offer the option of opening several Roth conversion IRA accounts under a single IRA plan, or opening each separate Roth Conversion IRA account in its own separate IRA plan. In the eyes of the IRS, does just having separate Roth conversion IRA accounts allow gain or loss in each account to be considered independently of the other Roth conversion accounts for purposes of calculating gain or loss on recharacterization? Or, is it necessary that each of the Roth Conversion IRA accounts be set up under a separate IRA plan by the brokerage house in order to consider gain or loss on recharacterization separately for each Roth Conversion IRA account?

Make sure to open separate Roth IRA accounts, not just separate sub-accounts.

Depending on the custodian, and IRS treatment, just opening separate sub-accounts may still subject you to the pro-rata share of gains & losses rule.

Even if your custodian is one that treats sub-accounts separately, it is better to be safe than sorry. And it is more likely that your 1099-R and 5498 will be calculated correctly by your custodian after you re-characterize, if you use completely separate accounts. Open as many completely separate Roth IRA accounts as necessary to accomodate your different investment strategies. It is worth the extra time now, to avoid potential problems later.

Hi Michael: I’ve researched everywhere and cannot get my question answered, including calling Fidelity (my custodian). My question is:

I have 4 Roth IRA’s titled as follows: Final: Roth #1: Roth #2 and Roth #3. I’ve separated 3 Roth IRA’s for conversion purposes. When I know that I will NOT recharacheterize, I consolidate/transfer the positions in the the “final” Roth IRA.

This year (2015), I converted 3 mutual fund positions into the my 3 Roth IRA’s (separately). Just this week, I plan to recharacterize ONLY 1 of the 3 Roth’s. The other two I plan to keep and journal the positions into my “Final” roth IRA.

Question: I understand I have to wait 30 days to convert again, however, does this 30 day window apply to all 3 roth IRA’s or just the one I recharactherized? Am I able to convert in early January those 2 roth’s that I didn’t recharacterized? Thanks Gregg

The 30-day restriction will only apply to the account that you re-characterized.

Per the IRS website (note especially the second-to-last sentence):

https://www.irs.gov/Retirement-Plans/Retirement-Plans-FAQs-regarding-IRAs-Recharacterization-of-Roth-Rollovers-and-Conversions

Is there a minimum waiting period to reconvert the money to a Roth IRA following a recharacterization?

Yes, if you recharacterize all or part of a rollover or conversion to a Roth IRA, you cannot reconvert the amount recharacterized to the same or another Roth IRA until the later of:

30 days after the recharacterization, or

the year following the year of the rollover or conversion.

The waiting period to convert applies only to amounts you recharacterized. For example, you can convert amounts from a different traditional IRA to a Roth IRA immediately.

Can like equities in separate accounts be utilized in this strategy? For example options on the same security in different accounts?

John,

Sure, you could have the same securities in multiple accounts with this strategy. But I’m not sure why you would want to? The performance will be the same if the securities are the same, so there’s no benefits to splitting them into separate accounts?

– Michael

I was considering using different vehicles (call vs put) to trade the same stock which would yield different results.

You were onto something very, very big John. Although tricky and tedious to execute, the strategy I believe you were envisioning, enabled you to convert unlimited amounts to a Roth IRA, almost tax-free. Sadly, I believe the new tax law eliminated recharacterizations, and all related strategies along with it.

I expected they would eliminate that option. Didn’t think it would be so soon. 2017 is the last year. April 15 is the deadline to recharacterize even if you file an extension. Next change will likely be that all earnings on Roths will be taxable.

You were on to something big. You could convert into two Roth accounts, do a bull call spread in one account, and a bear put spread in the other account, at parity. Recharacterize the losing account that went to zero, then repeat the splitting process with the winning account, until your tax liability on the conversion approached zero. Obviously, tricky to execute, and probably would have been challenged by The Service under the step-doctrine.

It looks like this strategy has been eliminated under the new tax law:

Subtitle F–Simplification and Reform of Savings, Pensions, Retirement

(Sec. 1501) This section repeals the rule that allows Individual Retirement Arrangement (IRA) contributions to one type of IRA (traditional or Roth) to be recharacterized as a contribution to the other type of IRA.

https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1

Christopher,

Alas, you are correct that TCJA invalidated this strategy by eliminating recharacterizations of conversions.

We’re still in the process of updating our prior articles for what has been altered by TCJA. Will get a notice added to this article soon!

– Michael

Michael,

That’s what I thought. Thanks for confirming. I shed a tear when I heard a couple months ago, that recharacterizations may be eliminated in the new law.

Thank you for explaining so many arcane strategies so well. You are truly brilliant. You inspire me.

Thanks again, and Happy New Year!

Chris