Executive Summary

The key benefit of specialized retirement accounts are their tax preferences – from the upfront tax deduction and tax-deferred growth of an IRA or 401(k), to the opportunity for tax-free growth from a Roth. Such tax benefits are intended to encourage and incentivize workers to save for retirement, and to make retirement at least a little more affordable. The caveat, though, is that if all the assets are not actually used for retirement, the retirement account – whether an employer retirement plan or an IRA, Roth or traditional – must be unwound, as eventually the Federal government does want to collect its share! Accordingly, IRC Sections 401(a)(9) and 408(a)(6) prescribe a series of somewhat-complex rules to determine exactly how fast a tax-preferenced retirement account must be liquidated after the death of the original owner, allowing the beneficiary in most cases to stretch out the tax impact over time (dubbed the “stretch IRA” strategy).

However, the reality for many couples – particularly single-earner households – is that the retirement account assets may be in only one spouse’s name, even though the savings were intended to support the couple jointly in retirement. And so in recognition of this dynamic, the tax code provides unique preferential treatment for a spouse who is the beneficiary of a retirement account, allowing not only more favorable stretch IRA (and stretch 401(k)) provisions, but also the opportunity for a spousal beneficiary to “roll over” the inherited retirement account and treat it as his/her own.

Yet while the additional flexibility of the spousal stretch IRA and the spousal rollover option are both more favorable than the standard rules for non-spousal beneficiaries of inherited retirement accounts, the special choices that spouses face have unique trade-offs. On the one hand, leaving an inherited IRA as such for a spousal beneficiary obligates him/her to take post-death Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) – potentially sooner rather than later – but avoids the impact of an early withdrawal penalty. A spousal rollover allows for the use of more favorable RMD tables, and may defer the onset of RMDs until even later, while also providing more favorable treatment for subsequent beneficiaries… but re-introduces the 10% early withdrawal penalty, which may be problematic for younger spousal beneficiaries (under age 59 ½).

Ultimately, the good news is that spousal beneficiaries have the option to make either choice, and even have flexibility about the timing – allowing a decision to maintain an inherited stretch IRA for the spouse initially, and completing a spousal rollover later (after he/she turns age 59 ½). Nonetheless, it’s important to carefully consider the choices and trade-offs… especially since a spousal rollover, once completed, is irrevocable and cannot be undone after the fact!

Spousal Rollovers Of Inherited Retirement Accounts

Under IRC Section 401(a)(9)(B), the standard rule for inherited retirement accounts (whether an IRA or an employer retirement plan like a 401(k), Roth or traditional) is that any remaining retirement account balance after the death of the original owner that is payable to a designated beneficiary shall be distributed “over the life expectancy, or over a time period not extending beyond the life expectancy” of that designated beneficiary. For the purpose of these rules, a “designated” beneficiary is defined in IRC Section 401(a)(9)(E) as “any individual designated as a beneficiary” – the key point being an individual (i.e., a human being that has a pulse and, thus, a life expectancy over which distributions can be stretched).

The requirement that distributions shall be payable “over a time period not extending beyond the life expectancy” of the designated beneficiary effectively sets a minimum floor on the amount of money that must be distributed from the inherited retirement account every year – thus why it is considered a “required minimum distribution” to that beneficiary. And notably, the requirement applies equally to pre-tax (traditional) and Roth-style retirement accounts, as while the tax treatment of the distributions may differ (with traditional account distributions being taxable and Roth distributions being tax-free), both are subject to RMD obligations after death. Though to the extent the beneficiary chooses to take only the required minimum amount for each distribution, and no more, it’s feasible to stretch out the inherited retirement account for years or even decades (thus known as the “stretch IRA”).

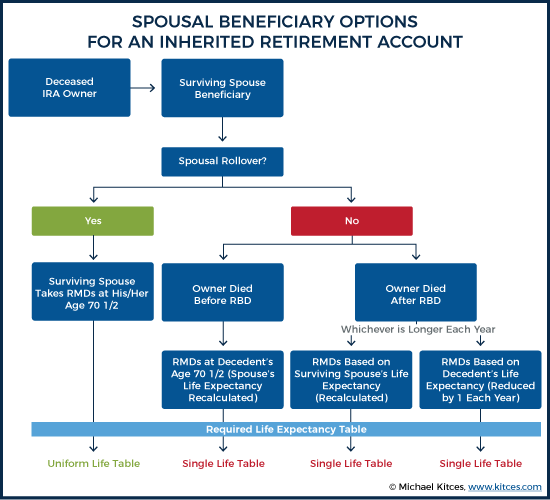

Yet while designated beneficiaries have the opportunity to stretch an inherited retirement account over their life expectancies, IRC Section 401(a)(9)(B)(iv) provides special (and even more favorable) post-death RMD rules in situations where a surviving spouse is the designated beneficiary of the retirement account.

Specifically, when a surviving spouse is named as the designated beneficiary, he/she has the option to roll over the inherited retirement account into his/her own individual IRA (or Roth IRA, in the case of an inherited Roth account), and continue the account as though he/she was the original owner. Although in order to qualify, the surviving spouse must actually be designated directly; a bypass trust for the spouse’s benefit is not eligible for favorable spousal rollover treatment (even if deemed a “see-through” trust), nor is naming a marital trust for the surviving spouse’s benefit, or his/her own revocable living trust, eligible for a spousal rollover (although PLRs 200317032 and 200520004 suggest that an IRA payable to a marital trust might ultimately be “rolled through” the trust as a spousal rollover, albeit with the cost of a Private Letter Ruling to “fix” what should have been a spouse named directly in the first place!).

The upside of the “spousal rollover” rule for an inherited IRA is that the surviving spouse will not even need to begin taking RMDs until he/she turns 70 ½ and reaches his/her own required beginning date. And upon reaching that date, the surviving spouse will be eligible to use the standard Uniform Life Table that applies to lifetime RMDs (rather than the less favorable Single Life Table that applies to beneficiaries of inherited retirement accounts).

Alternatively, a surviving spouse can still choose to leave an inherited retirement account as such – an inherited retirement account in the name of the original decedent, for which he/she is simply the designated beneficiary. And in such situations, Treasury Regulations 1.401(a)(9)-3, Q&A-3(b) also provides more favorable treatment than that typically available to designated beneficiaries – specifically, that the surviving spouse doesn’t need to start taking post-death RMDs in the year after death, and instead can wait until the year the original decedent would have reached age 70 ½ (or the year after death, if later). And in fact, under Treasury Regulation 1.408-8, Q&A-5(b), the inherited IRA for the spouse will automatically be deemed a “rollover” if the surviving spouse fails to begin post-death RMDs in a timely manner (or if he/she adds any new annual IRA contributions to the account).

Once post-death RMDs do begin for a surviving spouse via an inherited (and not rolled over) retirement account, those RMDs are based on surviving spouse’s age using the Single Life Table, but are annually recalculated in each subsequent year (rather than simply reducing the applicable distribution period by 1 in each subsequent year) under Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-5, Q&A-5(c)(2). As a result, the surviving spouse will be able to stretch the inherited retirement account even longer than other similar-aged designated beneficiaries.

Example 1. Fred passed away at age 62 in 2016, leaving a $400,000 IRA to his 60-year-old wife Ethel.

Under the normal rules for post-death RMDs to a designated beneficiary, Ethel would be required to take her first post-death RMD in 2017 (the year after Fred’s death). However, since Ethel is a surviving spouse beneficiary, she has the option to wait until the year Fred would have turned age 70 ½ (i.e., 2024) before taking her first RMD. And at that time, her applicable distribution period would be 18.6, based on her Single Life Expectancy as a 68-year-old, her age in that first future RMD year.

Alternatively, Ethel could also roll over Fred’s inherited IRA into her own individual IRA, and simply treat the account as though it was hers from the start. As a result, Ethel would not be required to begin taking RMDs until she turned age 70 ½ (in 2026), and would be able to take advantage of the Uniform Life Table (which at age 70 has a first applicable distribution period of 27.4 years).

In addition to the above options, if the original retirement account owner passed away after his/her required beginning date, there is also an option under Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-5, Q&A-5(a)(1) to take post-death RMDs based on the decedent’s life expectancy, rather than the beneficiary’s. As with any individual designated beneficiary who is older, this may potentially provide the surviving spouse a more favorable stretch period.

Example 2. Richard passed away at age 74 in 2016, leaving his $350,000 IRA to his 78-year-old wife Lucille. First and foremost, Lucille will be required to take Richard’s 2016 RMD in the year of death (if he hadn’t already before he died).

The first post-death RMD (as a beneficiary) from the inherited IRA will be due in 2017, and can be taken based on either Richard’s life expectancy factor (an applicable distribution period of 14.1 based on his age in 2016, reduced by 1 to 13.1 in 2017), or Lucille’s life expectancy factor (an applicable distribution period of 10.8, based on her then-recalculated age of 79 in 2017). If the 12/31/2016 balance of the IRA was $365,000, this would result in an RMD of $33,796 based on Lucille’s life expectancy, versus $27,863 based on Richard’s (more favorable) life expectancy.

However, in practice the opportunity to use either the decedent’s single life expectancy (reduced by 1 each subsequent year) or the beneficiary spouse’s life expectancy (recalculated each year) is a moot point, because the spousal beneficiary also has the option to roll over the IRA into his/her own name, which uses the Uniform Life Table that has even more favorable life expectancy factors (as it is based on the hypothetical joint life expectancy of the IRA owner and a 10-years-younger beneficiary, not just a single individual’s life expectancy).

Example 2b. Continuing the prior example, Lucille can also choose to simply roll over Richard’s inherited IRA into her own individual IRA.

As her own IRA, Lucille will be subject to RMDs based on the Uniform Life Table in 2017, which at her then-age 79 would be 19.5 years, resulting in an RMD of only $18,718.

In fact, because a spousal rollover uses the Uniform Life Table (based on joint life expectancies) while an inherited IRA only uses single life expectancy tables, it will virtually always be more favorable to roll over the inherited retirement account rather than leave it as an inherited IRA for stretch purposes (as shown below), unless the beneficiary spouse is much older than the original owner (such that the older surviving spouse’s joint life expectancy is still less favorable than the deceased spouse’s individual life expectancy).

Early Withdrawal Penalties And Spousal Rollovers For Surviving Spouses Under Age 59 ½

One important caveat to the decision of whether a surviving spouse should roll over an inherited retirement account, or not, is that once the account is rolled over, it is treated entirely as though it was the surviving spouse’s account to begin with. Which means RMDs don’t begin until age 70 ½, and will then use the favorable Uniform Life Table. But it also means that if the surviving spouse is under age 59 ½, the 10% early withdrawal penalty will apply to any distributions from the account!

By contrast, if the inherited retirement account is left (in the name of the decedent) and not rolled over, any money withdrawn from the inherited account will not be subject to the 10% early withdrawal penalty (as “distributions after death of the original owner” is an exception to the early withdrawal penalty under IRC Section 72(t)(2)(A)(i)). Thus, a surviving spouse who is under age 59 ½ will often prefer to leave the inherited retirement account as such – and not roll it over – to avoid any potential early withdrawal penalties.

Fortunately, though, there is no deadline on when a spousal rollover must occur, and it is possible to do so many years after the surviving spouse originally inherits the account. As a result, younger surviving spouses (under age 59 ½) may wish to simply leave the account as inherited until reaching age 59 ½, and then roll over the account into his/her own name once the early withdrawal penalty no longer applies (in order to obtain more favorable RMD treatment thereafter).

However, to retain the right to penalty-free distributions in the meantime, the surviving spouse must begin post-death RMDs on time (as required), and not add any new contributions to the inherited account, or the inherited retirement account will automatically be deemed a spousal rollover under Treasury Regulation 1.408-8, Q&A-5(b)!

In addition, to qualify for the “surviving spouse” treatment, the surviving spouse must actually be named directly as a beneficiary of the retirement account (not just payable to a trust or estate for the benefit of the spouse). Though notably, since the United States v. Windsor Supreme Court decision, and the subsequent Revenue Ruling 2013-17, same-sex spouses will also be recognized as surviving spouses for post-death RMD and rollover purposes, as long as the same-sex marriage was legal at the time and place it was performed.

Subsequent RMDs Upon The Death Of Surviving Spouse

The general rule under Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-5, Q&A-7(c)(2) for post-death RMDs in the event that the beneficiary of an inherited IRA passes away, is that the successor beneficiary simply continues the RMD schedule of the original beneficiary, and continues to reduce the applicable distribution period factor by 1 in each subsequent year.

Example 3. Charlotte, age 68, died on April 27th of 2016, and left the entire account to her then-44-year-old son Andrew (who had turned 44 in March of that year). Since Charlotte died in 2016, Andrew’s first RMD will be due by December 31st of 2017, and since Andrew turns 45 in 2017 (the first post-death RMD year), he will calculate his distributions based on the single life expectancy of a 45-year-old under the Single Life Table I of IRS Publication 590, which results in an Applicable Distribution Period of 38.8 years.

If Andrew subsequently passes away from an untimely death in 2022, his applicable distribution period would be down to 33.8 years. Accordingly, if Andrew now re-bequests his inherited IRA to his son Zachary (Charlotte’s grandson), then Zachary will simply continue the annual RMD process for the inherited account, taking Andrew’s RMD in 2022 (if he hadn’t already) based on the 33.8 year applicable distribution period, and then taking another RMD in the following year based on a 32.8 year period, then a 31.8 year period, etc.

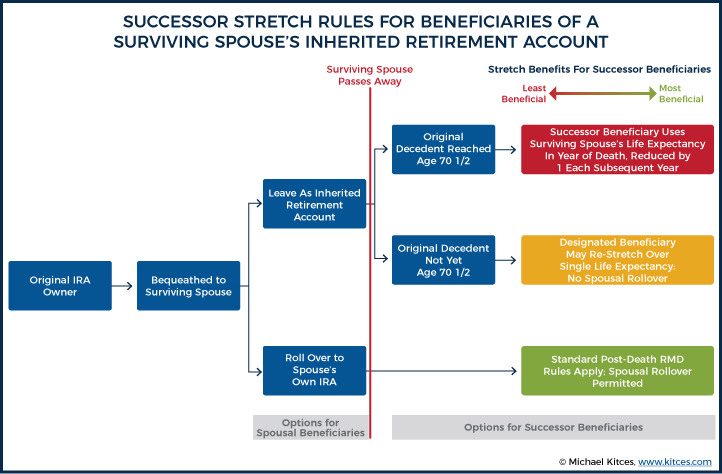

In the case of a surviving spouse beneficiary, though, the re-inheritance of the retirement account at the death of the surviving spouse is more complicated.

In the event that the surviving spouse kept the inherited retirement account, but was already taking post-death RMDs (i.e., because the original decedent was already over age 70 ½, or the surviving spouse had already waited until he/she would have been), then under Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-5, Q&A-5(c)(2), the surviving spouse’s life expectancy is last recalculated (one final time) in the year of death, and from that point forward the successor beneficiary simply reduces that applicable distribution period by 1.

However, if the surviving spouse kept the inherited retirement account, and was still waiting to take post-death RMDs until when the original decedent would have turned age 70 ½, then the rules are different. In this situation, Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-3, Q&A-5 permits the surviving spouse to be substituted in as though he/she were the original owner (even though the account was not rolled over), and any successor beneficiaries can reset the stretch period based on his/her own designated beneficiary life expectancy. However, if the surviving spouse remarried, that subsequent new spouse cannot (re-)roll over the re-inherited retirement account themselves.

On the other hand, if the surviving spouse actually already rolled over the inherited retirement account to his/her own name, then all of the rules are applied as though he/she was the account owner to begin with. Which means not only can subsequent designated beneficiaries stretch the inherited account based on their own life expectancies (or the decedent’s life expectancy, if death occurred after the Required Beginning Date), but a new spouse can then re-roll over the surviving spouse’s rolled-over retirement account as well.

Notably, from the planning perspective, given that post-death RMDs for successor beneficiaries are more favorable in rollover situations, especially if the surviving spouse remarried (and wants to allow the new spouse to re-roll-over the originally inherited retirement account), it may be beneficial to consider a “deathbed rollover” in situations where the surviving spouse has an inherited retirement account and becomes terminally ill.

Properly Executing The Post-Death RMD Process For A Surviving Spouse

When a retirement account owner passes away, the first obligation is to determine whether it is a traditional or Roth-style account, and if it a traditional account, determine whether the deceased owner was past the Required Beginning Date where lifetime RMDs would have been due (i.e., April 1st of the year after the year in which the decedent would have turned age 70 ½).

If the deceased was in lifetime RMD phase for a traditional (pre-tax) retirement account, then it must be determined whether that lifetime RMD was actually taken for the current tax year, and if not, the RMD amount must be distributed by the end of the current calendar year. The executor is responsible for completing the post-death distribution of the decedent’s last lifetime RMD, though notably, the final lifetime RMD should be paid out to the named beneficiary (or split amongst multiple beneficiaries based on their respective shares), not paid out to the decedent’s estate. Accordingly, the tax consequences of the final lifetime RMD distribution go to the beneficiaries that receive the amount, not the decedent’s final income tax return (nor the estate’s income tax return, unless the estate was actually the beneficiary of the retirement account).

Next, it’s necessary to re-title (or “re-register”) the deceased’s retirement account as an inherited retirement account. Some IRA custodians will require this to be done before the executor can make the distribution for the decedent’s final lifetime RMD to the beneficiaries, while others will allow it to be done at the same time, or shortly thereafter.

Re-registering the inherited retirement account entails changing its title from the original – typically as “<owner’s name>, IRA” into something that recognizes both the original (now-deceased) retirement account owner and the beneficiary, such as “<original owner’s name>, inherited IRA For Benefit Of <beneficiary’s name>, beneficiary”. Some inherited account registrations will abbreviate “For Benefit Of” down to “FBO”, and some will want to include the owner’s date of death in the registration as well. Because the beneficiary (or multiple beneficiaries) are typically named directly in the registration of the inherited retirement account when it is re-registered, the inherited retirement account is often split into separate accounts for each beneficiary at the time this re-registration process occurs (though it may be done later instead, if so desired).

If the surviving spouse intends to complete a spousal rollover, it is permissible to simply re-title the decedent’s original retirement account directly into the spouse’s individual Roth or traditional IRA (without first taking the step of re-titling it as an inherited IRA). On the other hand, since there’s no limit on when a spousal rollover occurs, there is no downside to first re-titling as an inherited IRA and then later completing the spousal rollover to the spouse’s own individual retirement account. In addition, because a spousal rollover – once actually rolled over – is truly treated as the surviving spouse’s own IRA, it is also permissible to add new IRA contributions to the account thereafter (assuming the spouse is eligible to make contributions in the first place), and the surviving spouse can even choose to simply roll over the inherited retirement account into an existing IRA as well (as there’s no reason to keep the spouse’s inherited and original IRA accounts separate once the spousal rollover has occurred).

However, it’s crucial to recognize that under IRC Section 408(d)(3)(B), an inherited retirement account is not eligible to be “rolled over” to an IRA, where the recipient takes a distribution and re-contributes it to a rollover account within 60 days, unless it is being done as a spousal rollover. In other words, while “regular” retirement accounts can be distributed and subsequently rolled over, once an inherited retirement account is distributed, its treatment as an inherited retirement account ends irrevocably and cannot be unwound and “put back”, which means the spouse must complete a spousal rollover (and face potential early withdrawal penalties if under age 59 ½) or simply report a taxable distribution immediately, and a non-spouse beneficiary is entirely “stuck” with an irrevocable (taxable) distribution.

Notably, this doesn’t prevent inherited retirement accounts from being moved to other financial institutions. But it means the move must be done as a trustee-to-trustee transfer of the inherited retirement account, with the transfer payable directly to the properly titled inherited account at the new IRA custodian. (This is also why it’s necessary to re-title the account as inherited before transferring it – because the receiving custodian will want to register the account as inherited, and the transferring custodian typically won’t release it if the receiving account has a different registration.) A true “rollover” – where funds are actually distributed as a check payable to the owner, who cashes the check, and then writes a new check to “roll over” the funds to a new IRA – is only permitted for an individual’s own IRAs, and not an inherited IRA (unless the inherited IRA becomes a spousal rollover account).

Once the inherited retirement account has been re-titled (and/or rolled over), the surviving spouse must still be certain to actually comply with the post-death RMD obligations, which apply equally regardless of whether the account was a traditional or Roth-style retirement account (as while Roth accounts have no RMD obligations during life, they are still subject to the same post-death RMD rules and calculations). If the account remains as an inherited IRA, the surviving spouse can generally still wait until the earlier of either when he/she turns age 70 ½ or when the original decedent would have turned age 70 ½, and in the event of a spousal rollover can similarly wait until he/she turns age 70 ½. Nonetheless, it’s crucial to begin RMDs in a timely manner once due, not only because the failure to take a timely RMD is subject to a whopping 50% excise penalty tax under IRC Section 4974(a) for the amount of the RMD not taken, but also because the spouse’s failure to take the first timely RMD from an inherited IRA will automatically be deemed a spousal rollover event (which may or may not have been the intended plan!).

So what do you think? How do you help clients evaluate spousal IRA trade-offs? What strategies do you find most useful when dealing with spousal IRA planning opportunities? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Isn’t the triangle approach a more detailed and comprehensive version of the rectangle approach?

Thank you – an education.

Very much appreciated.

It seems to me that the process is an interaction of the concepts behind each of the shapes. I usually start with a goals based approach and ask clients to think about what they would envision for a retirement life and contrast that with a known or knowable data set – current living costs. The latter is a real number that can serve as a powerful tool to define a start point from which one can adjust with a reasonable degree of confidence. My experience is that most people live in retirement about the way they lived prior. They may add some bits and pieces, but a lifetime of habits tend not to change very much. Travelers travel, spenders spend, the frugal aren’t comfortable becoming spenders. But to achieve the goal the rectangle must be considered as the framework to get to the goal, with the saving and investment strategy as the most effective way to do so. And then there is the acceptance of the reality for some that they cannot achieve that goal. But that only comes from “manipulating” all of the data, making certain assumptions, and bringing the bad news that one cannot get there from here. Or the good news that perhaps have already arrived!

Thanks – nice overview of different ways of viewing retirement planning through different “lenses”. imho the Triangle is the easiest for consumers to understand and frame their thinking around. If they decided to go with that framework, then they can decide how to fund their retirement in different ways – ex.

1) Needs – optimally used guaranteed income sources like Social Security, Pensions and Fixed Annuities (or low risk bond ladders).

3) Wants – investments with lower risk

3) Wishes – investments with higher risk – assuming you the person is not already financially set.

note: If you start factoring in other sources of wealth like human capital (part time work) & home equity OR get very aggressive in the expense area (ala the FIRE community) – that can dramatically change your overall plan and portfolio construction for these 3 components.

Regardless our view is the person should be financially educated and make decisions that they understand, make efficient use of their assets and maintain a living plan that they can manage or collaboratively manage, since no one can predict the future 🙂 .

This very comprehensive article gives the financial planner much to consider. However when sitting in front of a client looking to see if the recommended financial plan will meet their needs not only in retirement but other important milestones such as funding school fees, the planner would need to disguise the methodology whichever they chose as the best. Complex theories will most likely be too difficult for the average person to understand.

As the article suggests that most likely the best solution can be found in exploring all three methods to then customize a plan to suit the specific financial needs of the client.

The problem with these models is that they don’t take into consideration the one-off needs of the client. For example, what if they plan to buy a caravan on retirement, buy a new car every 7 years of retirement or have a long overseas holiday every three years for the first 10 years of retirement. With the right software these scenarios can be included for the client.

Talking with financial planners, I constantly hear the problem that the financial planning software they use does not allow them to quickly display alternative scenarios when the client asks ‘What if I want to ……’ There seems to be little software available which will dynamically change in front of the client, all the plan as alternatives are discussed and selected. More importantly, most modelling tools are only rudimentary and don’t allow one to explore a range of outcomes from that estimated in the final design.

For example, all planning software uses average returns to make long term plans. However, as financial planners, we are all acutely aware the rhythm of the economic cycle for interest earning assets, equities and real estate will vary every single year. What happens if the next ten years if there is a cycle where equities or real estate compare poorly compared to the other?

In my research I was able to distinguish four distinct 10-year economic cycles between 1986 and 2011. The four cycles showed one were equities was the outstanding performer, one where real estate was the outstanding performer, one where both equities and real estate performed well and at about the same rate. Finally there was one cycle, during the GFC, where having your money in interest earning assets was most likely the safest option.

How much more effective will it be for the financial planner to demonstrate to the client his preferred financial plan and then with the click of one button, demonstrate that while we are hoping for the outcome suggested, in reality, no one can predict the future, and one needs to consider what may happen if one of those four cycles were to repeat. This gives a range of outcomes from best scenario to worst. Looking at the estimated outcome with the possible best and worst outcome, should give more comfort to both the financial planner and the client that at least the basics can be met if the forecasted returns do not eventuate.

Coming from a family of doctors, I was always reminded that when a patient has seen their doctor about an important new adverse medical condition, they can only reminder about 10% of what doctor told them. I think that many clients of financial planners are the same. When it comes to numbers they are ‘brain dead’. How much better will it be for the client, if the planner can share the financial model they have recommended to client when they return home. This gives the client the option to consider all the outcomes, make changes, uses modelling tools and print short targeted reports which are easy to read and understand.

The key is using software which has the level of detail required for the planner, but simplicity of use that any consumer can use the product without any formal training.

I believe it is only when this occurs that client can truly appreciate the plans created by their adviser. They can instantly see how much they can draw-down in any year of retirement and from which funds that draw-down will occur.

Nearing my sixties with a daughter headed to college, so I’m using the Vanishing Green Rectangles approach.

This very comprehensive article gives the financial planner much to consider. However when sitting in front of a client looking to see if the recommended financial plan will meet their needs not only in retirement but other important milestones such as funding school fees, the planner would need to disguise the methodology whichever they chose as the best. Complex theories will most likely be too difficult for the average person to understand.

As the article suggests that most likely the best solution can be found in exploring all three methods to then customize a plan to suit the specific financial needs of the client.

The problem with these models is that they don’t take into consideration the one-off needs of the client. For example, what if they plan to buy a caravan on retirement, buy a new car every 7 years of retirement or have a long overseas holiday every three years for the first 10 years of retirement. With the right software these scenarios can be included for the client.

Talking with financial planners, I constantly hear the problem that the financial planning software they use does not allow them to quickly display alternative scenarios when the client asks ‘What if I want to ……’ There seems to be little software available which will dynamically change in front of the client, all the plan as alternatives are discussed and selected. More importantly, most modelling tools are only rudimentary and don’t allow one to explore a range of outcomes from that estimated in the final design.

Great piece, Michael. Is there really ever a scenario where a spouse beneficiary would want to do a spousal rollover if their spouse died before the RBD? Another thought: leveraging a spousal rollover for a portion of the Bene account in a situation where the surviving spouse needs to make an emergency or opportunistic loan to his/her-self – the thought being that he/she can leverage the accessibility of the Bene IRA and the consequence of blowing up the transaction for an under 59.5 y/o is reduced because of the exception to the penalty for that particular distribution.

Well, there is some “risk” in leaving the inherited IRA as such and not doing a spousal rollover – because subsequent treatment for future beneficiaries is potentially less favorable if the surviving spouse dies (and the original decedent was past RBD at that future point, and/or if the surviving spouse remarried and wanted to allow a re-rollover to the new spouse). So if there’s truly NO real need to leave it as inherited – i.e., the surviving spouse has ample other assets and resources – there’s really not much upside to leaving as inherited, and at least some risk of downside for an ill-timed or ill-coordinated death.

For those surviving spouses who will potentially need the money though – which is certainly common, especially when the surviving spouse is under age 59 1/2 and therefore likely to still be working and/or not yet able to afford retirement – clearly it’s often more favorable to retain the flexibility of keeping it as an inherited IRA (at least until the surviving spouse does turn 59 1/2).

– Michael

Excellent information. One question though, if I may. If a Spouse A does not rollover/take ownership of an IRA inherited from Spouse B, and correctly takes the RMD in the year Spouse B would have turned 70.5, but does not take the RMD the following year due to sickness and eventual death prior to year end, does the IRA remain as an inherited IRA from Spouse B or does Spouse A, by not taking the RMD in the year required, “assume” ownership of the IRA for the purposes of Spouse A’s heirs? Does Child A use Spouse A’s Age on the Single Life RMD table or does Child A use the Single Life RMD table for their age as though they were inheriting Spouse A’s IRA?

Very timely article. I hope everyone reads and digests it. We just had a situation in our family where the widow got terrible advice: her husband was 71, she was 50. He was retired, she’s still working. Her investment advisor started the paperwork to roll everything over to her name as a spousal IRA to stretch it. But my family member relied on distributions from the IRA to fund living expenses! The advisor was NOT a financial planner and forgot to ask the new widow how much of this money she’d need over the next ten years. The answer is quite a lot. In fact, she’s going to want a large distribution this year, while she’s still MFJ and has reduced income (unpaid time on leave with her ill husband) to fill up a bracket. Leaving a bunch of it as a non-spousal inherited IRA means she can take as much as she wants without penalty before age 59.5. Happily, I asked snoopy questions of a family member and was able to save the situation.

Wendy, thanks for this insightful comment. I’m in a similar situation right now with a young(er) widow, age 54. The only difference in her situation (and the reason I’m scouring Kitces) is that she’s her husband’s pension beneficiary. She wants/needs a distribution right away, without waiting to age 59.5. So I’m trying to figure out if she can open a non-spousal inherited IRA and roll the pension into it. Any insight?

I gather there was nothing in the TCJA about ending the stretch for non-spousal inherited IRA’s.

Excellent very detailed, Informative article.

Thanks a millions for your passion ,& to educate confused Taxpayers.

H. Malik

[email protected]

What if a spouse is named with another co-beneficiary as a Primary beneficiariay on the Inherited IRA (post RMD)? …can the spouse rollover her portion to her own or existing spousal IRA and treat as her own? Or because she is a shared primary bene, the non-spousal inherited IRA rules will apply?