Executive Summary

It's become a well-recognized phenomenon that life expectancies are on the rise, and have been for more than a century now. For many, this leads to the "inevitable" conclusion that someday we'll all be living to age 150 and beyond, and that we need to plan for drastically longer retirement time horizons - or even that retirement itself will be transformed (or become irrelevant) if medical breakthroughs allow us all to enjoy 100+ years of active lifestyles. However, a fresh look at the data reveals that this may not actually be the likely outcome.

In this guest post, Derek Tharp – our new Research Associate at Kitces.com, and a Ph.D. candidate in the financial planning program at Kansas State University – delves into the nuances behind the changes in mortality rates over the past century and in recent decades, and what they imply about the future.

Because the interesting phenomenon of recent advances in life expectancy in particular is that while overall life expectancies have been rising, most of the gains are attributable to people living closer to the maximum human lifespan (rising up towards about 115 years), and not as much from increases in the maximum age itself. And in the past two decades, the empirical data suggests that the maximum lifespan of human beings has stopped increasing altogether, peaking out around age 115. As a result, future medical advances may simply make us more and more likely to live to that maximum age, but there's little evidence to suggest that anyone is ever going to live to 150 and beyond... a phenomenon known as "squaring the (survival) curve".

The significance of rising life expectancy being due primarily to an increasing likelihood of living to maximum age, but not increasing the maximum age itself, is that retirement planning may need to adjust for a longer active phase of life... or more pessimistically, for prolonged periods of substandard health as what might have killed us in the past now simply slows us down! The potential for continued squaring the curve may also dramatically change the pricing and even the relevance of various types of insurance products, as long term care insurance becomes less necessary (if we're healthy for more of our lifespan), and annuity mortality credits become less available (because people die close together at the end of their maximum lifespan).

But the fundamental point is simply to understand that the ongoing rise in life expectancies doesn't necessarily mean that someday everyone is going to live to age 150 and beyond. It may simply mean that more of us will live to approach what appears to be a "maximum" human lifespan around age 115... and in fact, recent shifts in who is living longer (and who is not) suggests that we may have already hit that longevity wall.

Life Expectancy Assumptions In Retirement

One of the most important assumptions in any financial plan is life expectancy. Assuming too short of a lifespan can result in an excessively high withdrawal rate that depletes all of a client’s assets prior to death. However, despite a desire from financial planners to avoid ever seeing clients run out of money, assuming an unrealistically long lifespan is problematic as well. Excessively low withdrawal rates may lead to a lower quality of life in retirement, a larger than desired legacy inheritance (which the heirs probably won’t complain about, but the retiree might regret!), unfulfilled life goals, and—assuming there may be a relationship between life satisfaction and longevity—possibly even a reduction in lifespan itself!

However, “life expectancy” can be a somewhat misleading term. Many people hear the term and think of it as a measure of how long they can “expect to live”. In reality, though, life expectancy is a measure of the average time a person within some particular population is expected to live. While the average is meaningful in many respects, it may not always provide the best measure for setting expectations about the actual age someone is likely to reach. Because mortality rates aren’t constant across a lifespan and the distribution of ages at death are heavily skewed (i.e., more people die old than young), commonly cited life expectancy measures—particularly life expectancy at birth, which is most often cited in the media—may result in misleading expectations.

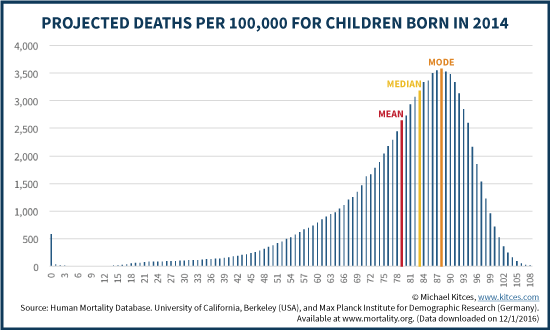

For instance, a child born in 2014 has a life expectancy (average age at death) of 79. However, the median age of death for the same child is 83, and the modal (most common) age at death is 89! Given the shape of the distribution of ages at death (negatively skewed), it’s simply a mathematical fact that the mean is going to be lower than the median or the mode.

Understanding Longevity Expectations With Survival Curves

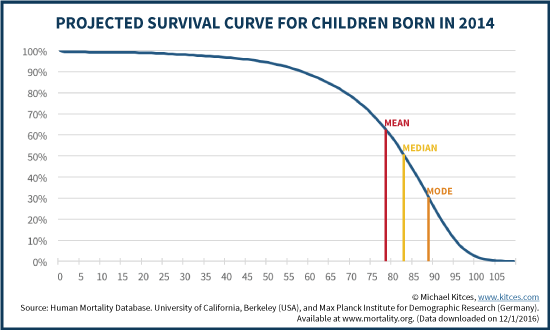

One way to explore some of the nuances within mortality figures is to visualize that data through the use of a survival curve – a figure which plots percentage of people still alive (i.e., the "survival rates" of a population) over time. Looking at the trends in how survival curves change over time can help us to not just see whether life expectancy is changing, but specifically where changes are occurring across the lifespan.

As you can see in the survival curve above, only roughly 1-in-10 people born in 2014 is expected to die prior to age 60 (i.e., 90% are still alive), but beyond that point, the rate of death begins to increase substantially. However, over 60% of children born in 2014 are still expected to be alive when the cohort reaches their “life expectancy” (i.e., average age at death) of 79. The median (age 83) is equivalent to the 50th percentile, and the mode (89) is roughly around the 30th percentile. By age 100, only 2% of people born in 2014 are expected to still be alive. While simple statistics like life expectancy certainly serve a purpose, survival curves give us a much better look at the “story” behind the data.

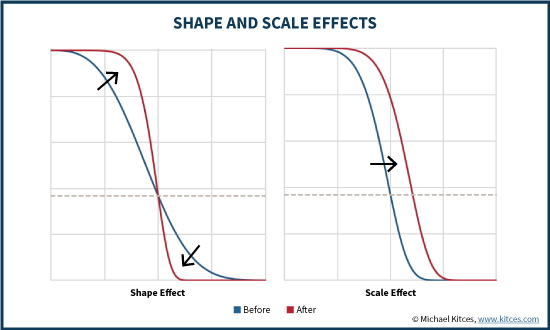

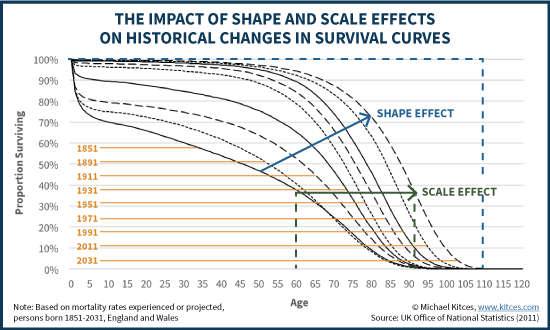

Demographers and population biologists identify two broad forms of change that can influence the shape of survival curves over time. There can be a “scale effect”, which refers to an increase in maximum age attained (i.e., the oldest people are reaching older ages), or a “shape effect”, which refers to changes in the curvature of a survival curve (i.e., more people are surviving long enough to approach or reach those maximum ages but not necessarily living longer than the maximum age).

This distinction is important because people often talk about rising life expectancy as though it goes hand-in-hand with increasing maximum age, but that’s not necessarily the case. In fact, when we look at how survival curves have shifted over time, changes have been attributable to both the shape effect (i.e., living closer to maximum age) and the scale effect (i.e., increasing the maximum age) at varying rates.

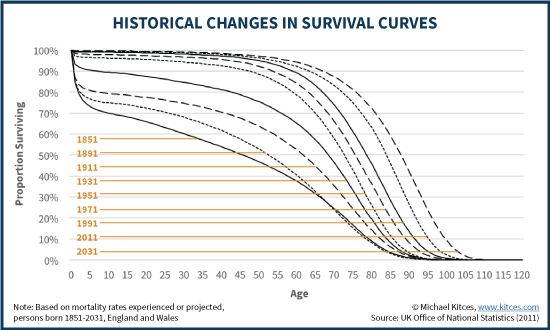

The graphic above shows experienced and projected survival curves from 1851 through 2031. The trends over time reveal one of the more interesting changes humans are experiencing in survival rates: while there has been some increase in the maximum ages, most of the change over time appears to be a “squaring-of-the-survival-curve” (which is also known as “rectangularization”). Squaring-the-survival-curve refers to the change in shape that results from people living closer to their maximum age without an equivalent increase in their maximum age. In a perfectly squared survival curve, nearly 100% of a population would survive to the maximum human lifespan and then suddenly pass away, forming a “curve” that takes the shape of a right angle (hence, “squaring-the-curve”).

Current Changes In Survival Curves

Survival curves are constantly evolving and subject to significant variation globally. A 2012 study published in Nature found evidence of variations in scale effects and shape effects even among relatively similar, wealthy capitalist societies. Though variations exist among societies, the long-term trends over the past several hundred years have shown both increases in maximum age attained and increases in the percentage of the population living closer to their maximum age, as noted in the chart above.

However, it’s possible humans in developed nations have recently reached a pivotal point in the evolution of our mortality. A 2016 study in Nature found evidence that the lifespan was increasing up until 1990, but has not increased since. In fact, the trend since 1990 has actually been a slight decrease in lifespan.

There is disagreement among researchers regarding whether a true maximum human lifespan exists, and exactly what that lifespan might be, but the same 2016 study in Nature found evidence that the human lifespan has plateaued around 115 years. This doesn’t mean no one will live beyond 115—Jeanne Calment was the oldest documented human at an age of 122 and few other exceptions have joined her living past 115—but the maximum age for all but truly the rarest exceptions appears to be stabilizing at 115, despite continued advancements in medical science.

Forecasting Changes In Advanced Age Longevity

It’s important to note that researchers are dealing with a relatively small sample when evaluating those approaching a maximum lifespan, so it is possible we are currently just experiencing some noisy data and lifespan will continue to increase in the future. Still, what we do know is that since 1990, almost all of the gains in life expectancy have been due to people living closer to their maximum age, rather than increases in maximum age. In other words, squaring-the-survival-curve now seems to be the sole driver of increasing life expectancies in developed nations.

The crucial insight from the phenomenon of squaring-of-the-survival curve is that increasing life expectancy does not necessarily mean increasing lifespans. At some point, we may see many (perhaps even the most!) people living beyond age 100, yet the likelihood of living to 125 may still essentially be zero! That’s not to say that we won’t encounter dramatic breakthroughs that fundamentally change these dynamics—for instance, technology that literally reverses aging—but barring any such technological breakthroughs, there is currently little foreseeable reason to forecast life expectancies beyond 115, even with ongoing medical advances. In other words, rising life expectancies don't necessarily mean we're likely eventually be living to age 150 and beyond... it may just be that we're increasingly likely to all make it right up to a "maximum" age around 115!

One potentially concerning behavioral consideration is the role that the availability bias may play in influencing longevity forecasts. Many clients forecast their own life expectancy based on the longevity of family members. While it appears that genetics play a significant role in longevity and it’s reasonable to take family health history into consideration, ironically, squaring-the-curve may mean that individuals with the lowest longevity expectations are actually the most prone to significantly outlive their expectations!

The reason is that people with longevity in their family already tend to die of old age, whereas families with without longevity often die of other health conditions. Yet, if squaring-the-curve results in increasing survival rates without a corresponding increase in maximum age, then the bulk of the gains in survival rates will go to those who aren’t dying of the same ailments that claimed the lives of previous generations. In other words, someone who has a family history of living into their 90s of 100s may have a good reason to believe they will also live that long, but there isn’t a huge risk they will live significantly longer. However, someone without longevity in their family who believes they will die in their 70s likely has the biggest “risk” of living 20-30 years beyond their expectations.

Individuals should also understand that average trends may not apply to them if their demographics make them significantly different from average. A recent report from the National Center of Health Statistics found that overall U.S. life expectancy dropped in 2015 for the first time since 1993. While it’s still possible this was just some statistical noise (and there’s some evidence that may be the case), it’s important to acknowledge that not every demographic experienced a decline in 2015. People seem relatively aware that differences exist among factors like gender, but it’s important to remember that race, education, wealth, income, and occupation are all important factors as well. Given the “typical” client of a financial advisor, these factors tend to be associated with more favorable life expectancies (relative to the average).

How Squaring-The-Curve Changes Retirement Planning

If we aren’t on a trajectory to live to 150, but instead, we’re on a path towards more and more people living into their 90s and 100s (and perhaps just a decade beyond), then this has some important retirement planning considerations. Most obvious, if we’re all dead by 115 but almost certain to be alive into our 90s or 100s, then (assuming norms surrounding retirement age don’t change) this will have the practical effect of increasing the length of the distribution phase of retirement, and, as a result, the assets needed for those entering retirement.

However, the good news is that for anyone who is already planning in accordance with distribution phase best practices, material changes to a plan may not be needed (at least not yet!). Most distribution research has historically used an assumption of a 30-year time horizon in retirement. Assuming a retirement age of 65, this still runs projections out until age 95, and for an average couple who has attained age 65, current joint mortality tables suggest that even just one of them living to age 95 or longer is only a 1-in-5 chance . And even with some continued squaring-of-the-curve, this assumption may be reasonably conservative for some time to come, particularly in light of how conservative the assumptions are that underlie the safe withdrawal rate, and the high likelihood that money withdrawn under the 4% rule will last more than 30 years anyway.

The more direct impact of increasing longevity will likely be on spending patterns throughout retirement. Just as we are starting to get a better grip on actual declining spending patterns of individuals in retirement, continued change among lifestyle factors may change these spending patterns further.

Notably, though, there are competing viewpoints on what these changes may look like. Some predict that squaring-the-curve will come from the ability to merely keep people alive (albeit possibly in a minimally-conscious and highly sedentary state). Under this scenario, life expectancies would be extended and healthcare expenses would increase, but it’s likely annual spending would decrease significantly within these final years of life.

More optimistic viewpoints see the extension of life coupled with more years of healthy life. In fact, gerontologists speak of different form of “squaring-the-curve” that comes from plotting quality of life over time – with an ideal of maintaining a high-quality lifestyle right up until death. Under this scenario, the decrease in retirement spending that is currently seen over time would be diminished. Not only would retirees live longer, but they would live longer with more years of higher levels of spending.

Of course, the optimistic and pessimistic views of squaring-the-curve are not mutually exclusive. It’s also possible—and perhaps, more realistic—that we’ll see a combination of longer time spent in good health and increased possibilities for extending life in poor health. Rather than the more gradual decline commonly seen in spending now, there may be an increased prevalence of steep declines in spending as the result of quicker and more dramatic lifestyle changes that coincide with rarer but more dramatic changes in health (that still can't be overcome by future medical science).

Another consideration is that if lifestyles become healthier and more active in old age, perhaps people will “retire” less—instead opting for "semi-retirement" consisting of scaled-back or different forms of work—and the nature of the need for income in retirement will begin to change. After all, retirement originated as something for people who were too old to work and became “obsolete” as workers. Its use as a time of leisure is a recent phenomenon.

It’s likely the meaning and conceptions of retirement will continue to change as well. When a retiree’s 60s and 70s are no longer their twilight years, will retirement itself become a less relevant milestone? Will new careers, civic engagement, or philanthropic work become even more prevalent in these stages of life? Will retirement become an even more popular transition as healthier retirees have even more to look forward to? Will the prospects of a longer, but perhaps less stressful career be more enticing than trying to save up enough to not work for many decades? Cultural shifts are hard to predict, but afforded the assurance that one is likely to live into their 90s or beyond (particularly in good health), it’s hard to imagine that cultural views on retirement wouldn’t change.

Farther Reaching Consequences Of Squaring-The-Survival-Curve

While squaring-the-survival-curve has many practical implications that affect the assumptions and practice of retirement planning, there are also some farther-reaching consequences that could influence the financial services industry more broadly, and are worthy of consideration.

Annuity Mortality Credits

One of the key benefits of annuitization is the ability to earn mortality credits. Mortality credits serve as a way to pool and spread out risk. However, in a world with a perfectly squared mortality curve, there would be no way to earn mortality credits. Everyone would live to their forecasted maximum age and then immediately pass away. Of course, this is an extreme example we are unlikely to see for a very long time (if ever!), but the general principle remains. As the distribution of age at death becomes more concentrated and uncertainty surrounding life expectancy is reduced, the conditions that make it possible to earn mortality credits are reduced as well. This may mean it’s a good idea to lock in mortality credit pricing in annuities today, but it may also mean that credit quality of the insurer is even more important, as low-quality annuity providers could be financially threatened if there is a dramatic squaring-of-the-curve with future medical breakthroughs!

Of course, the flip side of this is that as life expectancy becomes more predictable, the need to hedge against longevity is also reduced. If at some point in the future 95% of people are surviving to, and then dying between, the ages of 95-105, then retirement planning will have become a lot easier (at least from the perspective of dealing with one of the biggest planning contingencies of an unknown time horizon until death). It’s possible that future generations will look back and have as hard of a time fathoming our current mid-life mortality rates as we have looking back and fathoming maternal and infant mortality rates from as recently as the early 1900s.

Long-Term Care Insurance

Squaring-the-curve could have a tremendous impact on long-term care insurance, but the impact it has will ultimately depend on whether the optimistic or pessimistic perspectives on squaring-the-curve end up being more accurate.

If squaring-the-curve happens among both mortality and quality of life, then long-term care insurance could become largely obsolete. In fact, this may be what today’s still-struggling-to-be-profitable long-term care insurers are betting on (medical breakthroughs that turn their existing unprofitable policies into more profitable ones as claims decline)!

Alternatively, scenarios short of curve-squaring perfection could greatly enhance the risk characteristics of long-term care from a risk-transfer perspective. Ideally, insurable risks are high severity and low probability occurrences. With the expectation that 1-in-3 retirees will need some type of long-term care, the current characteristics actually aren’t great for creating products for the pooling and transfer of risk. However, with a healthier aging population and reduced need for long-term care services, long-term care insurance could significantly decrease in cost and begin to look much more like life or disability insurance does today – primarily used to address low frequency but high severity risks.

Increased Stress On Social Safety Nets

While living to 95 or 100 isn’t necessarily disastrous for the assumptions that go into current retirement distribution best practices, the reality remains that many Americans are simply not financially prepared for this type of longevity. As a result, squaring-the-curve will likely increase the amount of stress that already exists on social safety nets, such as extending and increasing the duration and amount of claims from Social Security and Medicare, not to mention the potential need to rely on Medicaid.

Of course, squaring-the-curve may have other effects that influence social safety nets as well. People in better health living more vibrant and active retirements may opt to delay retirement or engage in more work during retirement. Additionally, people may retain the ability to go back to work, even in “old” age. Particularly if the quality of life curve is squared as well, a retiree in their 90s may be much better equipped to re-enter the workforce in the event that they run out of money. Less extensive health care needs could reduce stress on certain social safety nets that provide health care as well.

Deeper Multi-Generational Families

Squaring-the-curve will likely influence generational family dynamics. Families with three, four, and possibly even five living generations will become more common. As families play an increased role as financial or personal caregivers across more generations, family relationships and support systems may become more complex.

Beyond pooling resources between generations, these changes could influence housing, caregiving, and child rearing. Multi-generational homesteads could become more common, and housing may need to adapt to provide the balance of independence and cohabitation families may desire. Adult children may continue to take a more active role in caring for elderly parents or grandparents, but at the same time, more active grandparents and great grandparents may play a larger role in raising and caring for children as well.

Generational transfers of wealth may also begin to change – not only because people are living longer, spending down their assets, and bequeathing less, but because of the greater need for assets to transfer up a generation or for inheritances to skip past generations (perhaps because children may commonly be in their 60s or 70s when their parents die and grandchildren or great grandchildren will be at a stage where they have greater needs for the inheritance). Or perhaps the ability to work longer will diminish the need for generational transfers as people can remain financially independent longer.

Mid-Career Investments In Human Capital

Few people today would seriously consider the possibility of going to medical school at age 50, but what would happen if they were relatively confident they would live to age 90? Four years of medical school and four years of residency may not seem so daunting to a 50-year old if they have a dream to be a doctor and the potential to still have a 20-year career with 10+ years in “retirement”.

In fact, a severe career reboot may be helpful in not only helping people pursue careers once they have a better idea of “who they are” and “what they want to do with their life” (i.e., they aren’t young adults with still developing frontal lobes), but also help facilitate a more efficient allocation of human capital. The effects of a higher willingness to re-invest in human capital mid-career likely wouldn’t be isolated to older adults either. The increased prevalence of older adults (even those in their 30s or 40s) pursuing entry-level positions in new fields or going back to school would likely result in competition that directly affects younger adults’ abilities to pursue these same economic opportunities.

The fact that life expectancy is rising is common knowledge, but the nuances behind that change are not. People are, on average, living longer, but that change isn’t necessarily the result of increasing lifespans. Rather, it is now the result of successfully living to our potential maximum lifespan and avoiding premature death.

That trend appears likely to continue, but if people are going to live healthy lifestyles into their 70s, 80s, and even 90s, there are implications for all areas of financial planning. Whether it’s our patterns of saving and dissaving across our life cycle, the financial products we use to achieve our goals, our living arrangements and family dynamics, or even our conceptions of work and retirement itself – squaring-the-survival-curve has profound implications to our clients’ finances and the goals we help them achieve.

So what do you think? Will maximum lifespans ever exceed 115-125 years? Are clients worried about the possibilities of living longer? How will financial planning be different if people regularly live 100+ years? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Thanks for the good posting this information.I have read your article briefly and check this blog …

winter survival kit