Executive Summary

For most financial advisors, the “ideal” client is one who simply delegates all decisions to the financial advisor. Delegator clients tend to allow the advisor to manage everything, and do so in a manner that lets the advisor’s expertise really shape the client’s financial outcomes.

Yet a new research study on delegation suggests that in reality, clients may not be delegating to advisors simply to let them deliver their expertise as efficiently as possible. Nor is it simply about delegating to save the time it would otherwise take to manage their own financial affairs. Instead, it turns out that the primary reason we delegate is so that we can absolve ourselves of the guilt and responsibility for a bad outcome. In other words, it’s all about having someone else to blame – i.e., the advisor.

However, from the advisor’s perspective, this is not necessarily a good thing. Because especially when it comes to managing a portfolio – or aiding clients with a goal that relies on market returns – the reality is that market outcomes, and the inevitable bear market that arises from time to time, is entirely outside the advisor’s control. And woe to the advisor who takes responsibility for bear markets they can’t necessarily avoid.

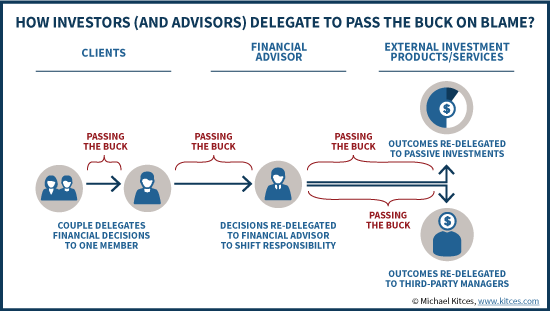

Of course, the reality is that the buck doesn’t have to stop with the financial advisor. In fact, whether it’s adopting a passive approach and blaming “the markets” themselves for the outcome, or hiring a third-party asset manager (whether as a mutual fund manager or a separately managed account) who can then be fired if results are poor, financial advisors have already adopted a wide range of approaches to avoid – or at least diffuse – the responsibility and blame for an unfortunate financial outcome.

Nonetheless, the reality remains that delegation may be less about finding expertise, and more about simply finding someone with the authority to accept blame and responsibility. Which suggests that financial advisors might even consider refining their marketing message, if the goal is to appeal to delegators, and recognizing the role we play in taking on at least some of the weight of responsibility. As long as the advisor remains cognizant of where to draw the line, to avoid being outright blamed, fired, or even sued, when the next bear market comes along!

Financial Advisors Typically Work With Delegators

The reality is that financial advisors don’t work with everyone. Many investors are “do-it-yourselfers” (DIY), who prefer to simply make their own financial decision and manage their own financial situation. After all, as the saying goes (amongst the DIY community), “no one cares more about your money than you do.” For those who have the time, inclination, and knowledge to be fully responsible for their own financial affairs, they can and do take the DIY approach.

However, not everyone is a do-it-yourself investor. Some recognize that they don’t have the knowledge and skillset to make good financial decisions, and need outside expertise. This may entail hiring a financial advisor to leverage his/her expertise about a particular topic or financial challenge, or even fully delegating financial decisions and responsibility to a financial advisor (e.g., to have full discretion to manage a portfolio). Especially in situations where the client is simply too busy – whether with work, or enjoying life or retirement – to take the time to fully manage their own financial affairs.

In fact, clients who are ready and willing to fully delegate to a financial advisor are often recognized as the “best” clients for advisors – the ones who by definition will hire the financial advisor for the most extensive range of services, and also tend to be the most hands-off in allowing the advisor to execute their role.

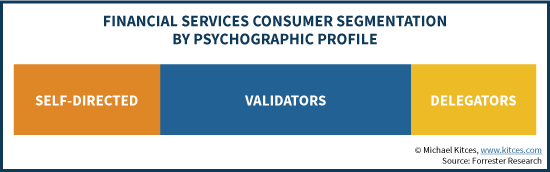

Notably, though, consumer segmentation research by Forrester finds that in reality, the majority of consumers are not full Delegators who give total discretion to advisors (nor full DIYs) in the first place. Instead, they’re “Validators”, who retain primary responsibility for their financial situations, while still seeking an advisor’s expertise to review and “validate” a financial decision.

In turn, though, the Forrester research raises an interesting question – if almost 3/4ths of consumers are interested in leveraging a financial advisor’s expertise, but of those only 1/3rd of them actually want to delegate while the other 2/3rds are validators, what is it about delegators that makes them want to delegate? And why do Validators still find value in an advisor’s expertise, but “not enough” to delegate to the advisor entirely? Is it simply because Validators have the time to still do most of the work themselves, while delegators are compelled to delegate due to lack of time? Or is it something else?

Delegation Is More About Passing The Buck On Blame Than Making Better Decisions?

A recently released study by Steffel, Williams, and Perrmann-Graham in Organizational Behavior And Human Decision Processes has attempted to delve into the driving factors that determine when and whether someone actually chooses to delegate or not. And as the name of the research implies – “Passing The Buck: Delegating Choices To Others To Avoid Responsibility And Blame” – it turns out that the driving factor to determine when and whether people delegate is not actually about the delegee’s expertise or available time at all.

Notably, research actually finds that in general, most of us prefer not to delegate at all. Instead, we like to have full control over our own decisions, at least/especially when we feel competent enough to make the decision. In fact, some research has already found that even when we’d be better off delegating, we still tend to keep responsibility for decisions, just because we like to have the control.

Sometimes, though, we really don’t want to have to make a decision. Perhaps it’s too hard or complex and we feel we don’t have the expertise. Or we’re just too tired and don’t have the time to weigh the options. If it’s not a serious issue, we may just engage in the easiest version of “choice avoidance” and defer it indefinitely. But for high-stakes issues, where a decision has to be made, and we don’t want to make it (or be the person who makes it), then it’s time to delegate the decision to someone else.

Yet when the researchers delved deeper, what they found is that the driving factor about whether someone chooses to delegate a decision is not just about handing off decisions to someone else who might have the time to do the analysis and the expertise to make a better choice. Instead, it turns out that the driving factor in the decision to delegate is a desire to avoid feeling responsible for the outcome.

In other words, people are most likely to delegate a decision when the person being delegated to can be blamed for the decision if there’s a bad outcome. Accordingly, the researchers found that people are much more likely to delegate to those with “high status” – who are in a role that has the authority to be responsible for the decision, and accept the blame. Especially when there are potentially negative outcomes, such that there’s a real possibility that there will be an unfavorable result for which someone needs to be blamed.

Furthermore, Steffel and her colleagues found that because assigning blame in the decision to delegate is so important, it requires having another person be involved in order to have someone to blame! As a result, the study found that if people had a chance to resolve a difficult decision by delegating it to someone else, or simply flipping a coin (and letting chance determine the outcome), there was a clear preference to delegate to another person and not just leave it to chance. More generally, it appears that the challenge with trying to ‘delegate’ to any form of inanimate object (e.g., a computer) or game of chance is that while it might ease and simplify the decision-making process, it still leaves the user as being primarily responsible for the decision (because they still chose the computer program or coin flip). Which in the case of delegation, isn’t enough, because there’s no one to shift the blame to if the outcome is unfavorable.

In essence, the researchers found that delegating to an expert is not so much about getting a better answer to a difficult question or decision, but about avoiding the responsibility that comes with making the “wrong” choice. In fact, the role of shifting responsibility was so important that people were more likely to delegate for responsibility regardless of expertise.

Why Do Clients Delegate Financial Decisions To Financial Advisors?

While financial advisors tend to focus on their value proposition as being their expertise and ability to (efficiently) help clients make financial decisions (or outright manage portfolios on their behalf), the Steffel et. al. research suggests a substantially different perspective on the advisor-client delegation relationship – that advisors aren’t merely being hired for their expertise, but for the client’s ability to absolve their own guilt/blame/responsibility if a decision goes wrong (e.g., an investment goes south).

In other words, perhaps a material portion of an advisor’s AUM fee for the discretionary management of a portfolio is not for their actual stock-picking or investment selection prowess, but simply for taking on the responsibility for the portfolio’s outcomes.

And given that the researchers found that people are 2-3 times more likely to delegate when their decisions could have an adverse impact on others, the delegation of responsibility and blame may help to explain why couples and families in particular engage advisors so frequently – not because their family situations are more complex, but because the dynamics of blame are more consequential. In other words, it’s nice to delegate to a financial advisor so you don’t have to feel as responsible for the potentially bad outcomes, but it’s really nice to delegate to an advisor if you’re married and don’t want to have to answer to your spouse for why your retirement portfolio is down.

In turn, this helps to explain why clients are so apt to blame their financial advisor when the markets take a downturn. Because the whole point of delegating was, at least in part, to have the advisor to blame if a negative outcome occurred!

On the other hand, this also raises a significant concern for the advisor – while the research suggests that clients might be hiring a financial advisor as a way to assign the blame if there’s a bad financial outcome, advisors don’t actually control what the markets do. Which means there’s a risk that the advisor is taking on the responsibility for an outcome they can’t necessarily impact – at least not fully – but in the extreme could be blamed for… and even sued for.

Third-Party Asset Managers And The Re-Delegation Of Blame And Responsibility

While the prospective appeal of delegation for an individual working with a financial advisor is that it provides the client the opportunity to shift responsibility (and potential blame) for unfavorable outcomes, it’s notable that delegation isn’t limited to what the client does. The financial advisor can delegate as well. In fact, Steffel et. al.’s research was focused on those very situations where (in businesses) people who are delegated to then re-delegate a task to someone else, effectively “passing the buck” along.

And the researchers found that people are especially likely to (re-)delegate tasks when the potentially negative outcomes impact not only themselves, but others as well… which is the precise context of the financial advisor who is making financial decisions and recommendations on behalf of a client. Because just as the task may have been delegated to that person (the financial advisor) for the client to absolve their blame and responsibility, so too may the advisor want to re-delegate the task to further shift the responsibility and potential blame down the line! (The effect was so strong in the research that even when delegees knew they couldn’t be blamed directly, they still tended to re-delegate tasks that could have negative outcomes for others, simply because they felt the self-imposed weight of responsibility!)

The desire to re-delegate to avoid potential blame for unfavorable outcomes helps to explain why so many advisors use and rely upon third-party investment products and solutions, from mutual fund managers to separately managed accounts and third-party asset management (TAMP) providers. Because they all create some path for advisors to re-delegate the responsibility that was originally delegated to them. Thus, when an investment turns out poorly, it’s not the advisor bearing the blame for poor investment results; instead, it’s the advisor sitting on the client’s side of the table, jointly blaming the third-party investment manager for the bad outcome.

Similarly, the desire to manage exposure to blame also helps to explain why advisors so often defer to “the markets” in the first place, including the use of index funds and ETFs. Because when the investment approach is passive in the first place, the advisor ostensibly cannot be blamed for the outcome; the markets (or market factors) will do whatever they do. In other words, from the advisor-client perspective, one virtue of passive investment approaches is that they facilitate the advisor’s attempt to show that portfolio results are largely out of the advisor’s control (such that the advisor shouldn’t be blamed). Of course, this also has the benefit of being true – the overall direction of the markets really is beyond the advisor’s control, and he/she shouldn’t be blamed for the outcome.

Nonetheless, the common focus of client conversations on this dynamic, whether it’s blaming the markets in a passive approach, or blaming third-party managers in an active approach, is that it simply reinforces the reality that often a key role of the advisor is “being ‘someone’ to blame”… which in turn creates pressure on the advisor to manage that blame exposure, or shift it to the extent possible, to minimize the risk that it actually does lead to the advisor being blamed, fired, or sued.

Implications Of The Financial Advisor Delegation Blame-Game

For most financial advisors, the idea that clients want to be able to blame the advisor for a bad outcome is downright terrifying, given that markets can’t be controlled and that bear markets are inevitable for anyone who stays invested long enough. In point of fact, it’s already a reality that the number of complaints and lawsuits against financial advisors spike whenever an (uncontrollable) bear market occurs. And accordingly, it’s not surprising that as advisors, we end out spending a lot of time simply trying to manage client expectations about market volatility, and making it clear that portfolio losses aren’t actually our fault… whether it’s because “the markets did it” to a passive portfolio, or if it’s due to underperformance of an active manager that the advisor and client will now work together to fire and replace.

Yet at the same time, the research on delegation suggests that financial advisors might have more success gaining (delegator) clients if they were clearer about taking on at least some responsibility for a client’s financial decisions (and implicitly their potential outcomes). Of course, this certainly wouldn’t amount to saying “we’ll take full blame for any market losses”. But it could mean making statements like:

Financial Advisors: We take responsibility for worrying about your portfolio, so you can take responsibility for enjoying your life!

Financial Advisors: When you’re tired of being blamed by your spouse for market volatility, we’re here to help.

Financial Advisors: You can rely on our expertise to guide your financial decisions. (Where it’s not actually about the expertise, but the opportunity for the client to rely upon it and not be responsible!)

On the other hand, the dynamics of the delegation blame-game also helps to explain why “pure” robo-advisor solutions are struggling, while cyborg platforms (tech-augmented humans) are doing so much better: because the robo-platform may provide the automation and the expertise, but it’s not effective for assigning blame. As the researchers found, we just don’t gain the blame-game satisfaction by delegating to games of chance or inanimate objects like computers; for better or worse, human beings are social animals, and we’re wired to blame other human beings. But that means there needs to be a human as a part of the picture, so that we have someone to blame (or at least, to complain to when there are unfavorable results).

And unfortunately, the delegation blame-game also helps to explain why so many advisors with a strong personality and sales skills, but little actual competency, still succeed in gaining clients. Because, as Steffel and her researchers noted, the decision to delegate is more about the perceived authority of the delegee to accept the blame, than their actual expertise to make a better (financial) decision. In other words, as long as the client trusts the advisor and is willing to give them the responsibility, the fact that they’re perceived as trustworthy enough to handle the responsibility ends out being more important than their actual ability to execute that responsibility. (And of course, there’s also the unfortunate challenge that not every client is a good judge of character and trustworthiness in the first place.)

In fact, the desire to find someone who has the authority to accept responsibility may even partially explain the rapid growth of the entire AUM model in recent years, and the consumer shift from broker-dealers to RIAs – it’s not merely about the difference in business models and conduct standards, but the fact that the discretionary management services of RIAs are more of a blame-shifting delegation than merely using a broker to buy some mutual funds (where the client still feels at least partially responsible for the decision).

The bottom line, though, is simply this: as much as financial advisors try to provide value by using their expertise to help clients make better financial decisions, the reality is that a material portion of the advisor-client relationship may be about shifting responsibility for the outcome of those decisions as well. Which means on the one hand, advisors must be careful not to accept so much responsibility that clients fire or sue them when a bear market occurs (given that it’s beyond the advisor’s control). Yet on the other hand, recognizing that clients who delegate are actively seeking an opportunity to shift some responsibility for the outcomes of their financial decisions may actually be an opportunity to better connect with client needs… as long as the advisor has a clear strategy about how to ensure he/she isn’t ultimately blamed for an unfortunate outcome beyond his/her control!

So what do you think? Is delegating to a financial advisor really more about shifting responsibility and blame, than hiring for expertise alone? Is that an unfair expectation for financial advisors, or a reality we must embrace? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!