Executive Summary

While it’s commonplace for investors to hold multiple investments in a portfolio – often comprised of mutual funds or ETFs that in turn hold dozens or even hundreds of underlying positions – the reality is that even multi-asset-class portfolios aren’t always really diversified.

The fundamental problem is that holding many different investments that are all aligned to the same “base case” market scenario – and all go up together – may be equally at risk to decline together if an adverse event happens instead.

For instance, a “well diversified” portfolio holding US stocks, emerging markets, commodities, and corporate bonds, may be invested into multiple asset classes – but they would all be expected to go up in a growth environment, and all would likely decline severely in a recession!

Of course, the investments that don’t go down in a recession, from “defensive” stocks to government bonds, are also the investments likely to perform the worst if markets continue to rise. But in the end, that’s the whole point of diversification – to own investments that will defend in the risky events, even if it means giving up some upside in the process. Or viewed another way, being well diversified means always having to say you’re sorry about some investment that’s not moving in the same direction as the rest!

And given the complexity of today’s investment environment, and the typical multi-asset-class portfolio, a growing range of tools are becoming available to “stress test” various risky scenarios, to help determine whether a portfolio is truly diversified, or just holds a large number of investments that are all expected to go up – and down – in an undiversified manner!

The Origins Of Portfolio Diversification

The roots of diversification trace back thousands of years. The Jewish Talmud illustrates the principle of diversification by stating “it is advisable for one that he shall divide his money in three parts, one of which he shall invest in real estate, one of which in business, and the third part to remain always in his hands,” (Tract Baba Metzia), and the Bible recognizes the importance of diversification even more directly: “But divide your investments amongst many places, for you do not know what risks might lie ahead.” (Ecclesiastes 11:2).

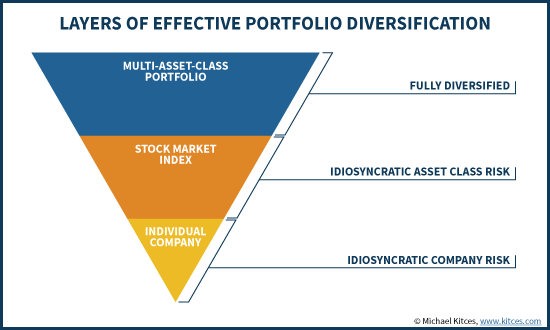

In the modern context, the Bible’s unknown risks that may lie ahead are further divided into two subcategories: idiosyncratic risk that is specific to a particular investment (also known as “unsystematic risk”), and systematic risk that an investor takes on by investing in the markets at all (also known as “market risk”). The distinction is important, because the finance research has shown that by owning a sufficient number of individual stocks, an investor can diversify away the specific company risk of any particular stock in the portfolio. However, because all the stocks are still tied to (and in fact comprise) the stock market, the investor cannot fully diversify away the aggregate risk of the market itself.

Of course, it is still possible to diversify out of the stock market itself, which in fact was what the Talmud prescribed by indicating that only 1/3rd of assets should be invested into businesses, with the other 1/3rd in real estate (an entirely different asset class), and the last 1/3rd in cash. More generally, this means that the next layer of diversification is to spread assets across entire asset classes – ideally ones that are so different from each other that the “idiosyncratic” risks of one asset class in the aggregate are still not shared by the others.

In other words, broader and broader diversification is simply about spreading investments out to minimize exposure to any one of a broader and broader range of potential risks.

Diversification Means Always Having To Say You’re Sorry

The principle of diversification is to spread out an investor’s exposure to various risks, so that if the risky event occurs, not all investments are adversely impacted. But an important corollary of diversification therefore applies as well: if the risky event does not occur, not all the investments will benefit, either.

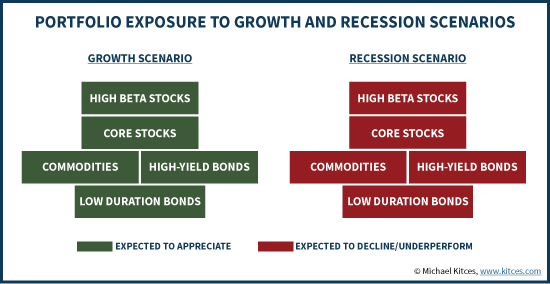

For instance, imagine a portfolio that’s invested on the base case that the economy is healthy and will keep growing. Such a portfolio would have a healthy allocation to equities, along with exposure to commodities, and would likely tilt towards more volatile “higher beta” stocks (e.g., small cap and emerging markets). A strong economy also tends to keep the default rate low, so the investor would likely also favor corporate bonds over government bonds (and “ideally” high-yield bonds with the greatest return boost in a low-default environment). Any interest rate sensitivity (i.e., duration) would be kept low, as a strong economy is likely to eventually face rising interest rates.

However, the fundamental problem with such a portfolio is that while it’s spread out across a number of different asset classes, it is actually very poorly diversified, because the portfolio actually just owns multiple asset classes all aligned towards the same risk – benefitting as long as the economy grows, and at risk if a recession occurs.

After all, if we look from the risk side of the spectrum, what happens if the base case for economic growth is wrong and a recession does occur. Markets will decline, with the most volatile “high beta” stocks falling the most. Default rates will rise, leading to widening spreads that hammer the price of “high-yield” corporate bonds. And if the Fed responds by trying to cut interest rates – or more generally, interest rates decline in anticipation of the lower real return environment – the portfolio’s low duration will not provide much benefit, either!

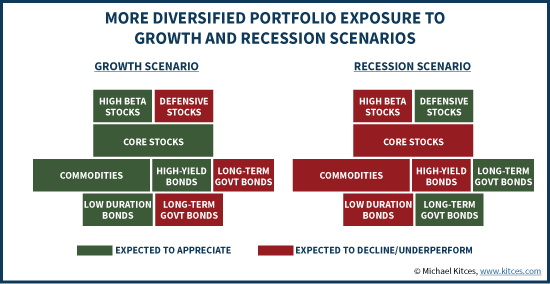

Which means if the reality is that the investor truly wants to be well diversified, it’s necessary to own investments that will perform well in the risky scenario (the recession), even if it means that investment will perform poorly and not work out well if growth is good and the markets are up. For instance, the portfolio would eliminate some of the high-beta stocks to own defensive stocks, and would carve out some of the high-yield and low-duration bonds to own long-term government bonds.

If the recession scenario occurs, the more defensive stocks, along with the government bonds, will perform well. Of course, if the growth scenario continues to play out, those same allocations will be the worst performers in the portfolio. But that’s actually the point – if the portfolio is well diversified against the risk of a recession, it will also be diversified enough to not perform as well if the risk doesn’t occur!

Or viewed another way, being truly well diversified means always having to say you’re sorry about some investment that’s not moving in line with the rest of the portfolio, to the upside or the downside!

Optimal Diversifiers – Correlated In Bull Markets But Not In Bear Markets

A notable caveat to the principle of diversifying by owning investments that will go up whenever else goes down is that if they always go down when everything else goes up, the portfolio doesn’t necessarily end out ahead. For instance, an investor could simply buy an inverse ETF fund – or in the extreme, a leveraged 2X or 3X inverse fund – and it would be assured of going up when the market goes down… but given that the market goes up more than it goes down, will really just drag down the long-term return of the portfolio! Diversification should still never be an excuse to own an outright inferior investment with no long-term return potential!

Ideally, then, the goal is to either find an investment that still has reasonable long-term returns, but just has an outright low correlation, or even more ideal an investment that has a correlation that is positive in up markets but a lower correlation (i.e., is a better diversifier) when markets are down.

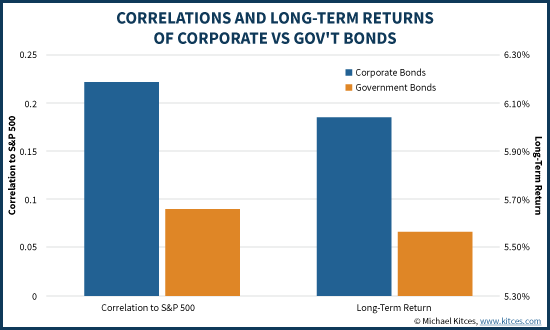

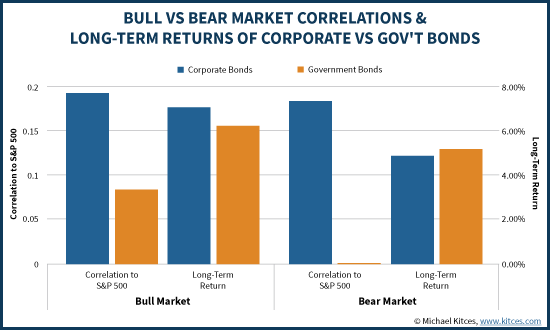

A case-in-point example is a comparison between corporate bonds versus government bonds in a portfolio. Both have fairly low correlations to the market overall – the rolling 12-month correlation between the S&P 500 and long-term corporate bonds is only 0.22, and the correlation between the markets and long-term government bonds is just 0.09. In this context, government bonds would be viewed as a slightly better diversifier than corporate bonds – given the low correlation – but unfortunately this superior diversification comes at the expense of long-term returns: the long-term average annual compound growth rate of (long-term) corporate bonds is about 6.0%, compared to just 5.6% for (long-term) government bonds.

However, the long-term correlation and returns of these investments are somewhat misleading, because they are not consistent throughout the economic cycle.

For instance, amongst all the historical rolling 12-month periods where the return on the S&P 500 is positive (based on Ibbotson monthly data), the average return of corporate bonds is a whopping 7.0%, and government bonds trail even more with a return of only 6.2%. In these environments, the correlation of corporate bonds is 0.19, while government bonds is 0.08.

However, in the historical rolling 12-month periods where the return on the S&P 500 is negative, the average return of corporate bonds falls to just 4.7%, while government bonds have a superior return of 5.0%. In the process, the correlation of corporate bonds holds fairly stable at 0.18, while the correlation of government bonds to the S&P 500 falls straight to 0.0!

In other words, it may appear that government bonds having a slightly lower return (compared to corporate bonds) in exchange for providing a lower correlation to the S&P 500. But as a diversifier government bonds are drastically better, because they underperform corporate bonds when stocks are already up, but outperform corporate bonds when stocks are down and it matters the most! Or viewed another way, the government bonds are the better buffer against bear market declines, and the lower return in a bull market is simply the price to pay – but, notably, a price that shouldn’t matter much because stocks are already making huge returns in a bull market anyway!

Stress Testing The Risks To Ensure You’re Diversified?

One significant challenge of crafting a well-diversified multi-asset-class portfolio is that not all risks impact all asset classes in the same way – in fact, arguably the reality that certain investments may respond differently to a similar risky event is what defines them as different asset classes!

For instance, consider the case of inflation. Both stocks and commodities react well to modest inflation, but significant inflation may be especially good for commodities while turning bad for stocks (in part because the more-expensive commodities cause higher input costs that drive down the price of stocks!). Similarly, modest inflation may allow government bonds to perform well, but significant inflation forces interest rate increases that adversely affect interest-rate sensitive bonds. On the other hand, corporate bonds may perform especially well in a rising inflationary environment, as companies eventually pass through price increases that lift their nominal earnings and make their debt easier to service (even if real earnings are not rising).

Different asset class dynamics can also apply to deflation (and may vary depending on the cause of deflation), growth vs recession environments, rising vs falling interest rates, or even times of peace vs environments with geopolitical unrest.

The added complexity to investing in this manner, as noted earlier, is that not only do different asset classes react differently to external events, but their reactions are not always symmetrical. Deflation is more severely bad for commodities than inflation is good. Modest inflation is good for stocks, but severe inflation can be bad (and deflation is bad, too). Government bonds underperform corporate bonds in growth environments, but outperform them in the recessions when they’re needed most for diversification.

These dynamics mean that in practice, it’s not enough to simply look at basic portfolio statistics such as long-term average correlations. Instead, portfolios must be evaluated for their exposure to specific risks, with recognition of how the portfolio might respond to those particular risks – and ensuring that there is a healthy level of diversification to a wide range of possible outcomes.

![]() Fortunately, a growing number of tools are becoming available to advisors specifically to analyze and “stress test” such scenarios. Companies like Hidden Levers, RiXtrema, and

Fortunately, a growing number of tools are becoming available to advisors specifically to analyze and “stress test” such scenarios. Companies like Hidden Levers, RiXtrema, and  MacroRisk Analytics all provide solutions for advisors to input portfolio allocations, and evaluate how the portfolio might respond to scenarios from an inflation shock to a further oil crash, from inflation picking up or rolling over into a deflationary direction.

MacroRisk Analytics all provide solutions for advisors to input portfolio allocations, and evaluate how the portfolio might respond to scenarios from an inflation shock to a further oil crash, from inflation picking up or rolling over into a deflationary direction.

The purpose of all these tools: to identify scenarios where a portfolio is “too aligned” towards a single outcome, and thus over-exposed to the potential of being wrong (or outright unprepared for a risk to occur).

The purpose of all these tools: to identify scenarios where a portfolio is “too aligned” towards a single outcome, and thus over-exposed to the potential of being wrong (or outright unprepared for a risk to occur).

As with all of these uncertainties, there is still some “base case” scenario that is most likely to play out – inflation is more likely than deflation (at least in the modern era), peace is more likely than an actual geopolitical war, and even though recessions may be “inevitable” growth is still more likely to occur from year to year (all else being equal). Still, the point of diversification remains the same: even if the expectation is for growth, modest inflation, and peace, there’s still a risk of recession, deflation, or a geopolitical crisis. Which means the portfolio should hold some investments that will perform well in these scenarios, even to the detriment of underperforming if everything else is working out as planned!

So what do you think? How do you evaluate whether a portfolio is really diversified? Do you segment the portfolio into its diversification in bull versus bear markets? Have you ever tried portfolio stress testing? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!