Executive Summary

In December of 2019, Congress passed the Setting Every Community Up For Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act, introducing substantial updates to the laws governing retirement accounts. Changes to post-death distribution rules resulted in the death of the ‘stretch’ provision for certain (most) non-spouse Designated Beneficiaries of inherited retirement accounts and introduced a new “10-Year Rule” for account distributions, which have important implications, not just for the Designated Beneficiaries of those retirement accounts, but also for their Successor Beneficiaries as well.

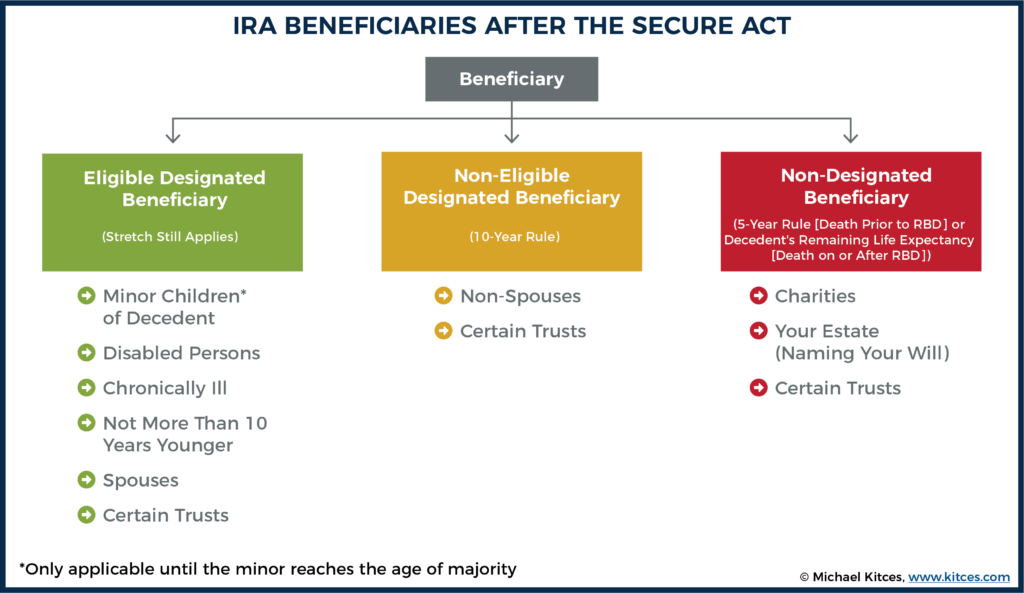

Prior to the passage of the SECURE Act, Designated Beneficiaries of retirement accounts were allowed to ‘stretch’ Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) from the account over their own life expectancies. However, the SECURE Act eliminated the stretch option for most non-spouse Designated Beneficiaries, and instead, requires the account to be emptied by the end of the 10th year following the year of the original owner’s death. The SECURE Act, however, also created a new category of beneficiaries – Eligible Designated Beneficiaries – that is still permitted to use the ‘stretch’ provision.

Any of these beneficiaries, of course, could, themselves, die prior to emptying their inherited retirement accounts, leaving the balance to a Successor Beneficiary. Accordingly, there are now three potential scenarios for Successor Beneficiaries of inherited retirement accounts: 1) Successor Beneficiaries of post-SECURE-Act-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, 2) Successor Beneficiaries of pre-SECURE Act Designated Beneficiaries, and 3) Successor Beneficiaries of post-SECURE Act Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries.

In scenarios 1) and 2), Successor Beneficiaries will generally be subject to the full 10-Year Rule. One exception to this is if the post-SECURE Act Eligible Designated Beneficiary (or pre-SECURE Act Designated Beneficiary) is the surviving spouse of the original account owner and dies before the decedent would have been required to begin taking RMDs. In such cases, upon death, they are no longer be considered a “Designated Beneficiary” of the account, but instead, are treated as if they had been the original account owner. Thus, the Successor Beneficiary wouldn’t be treated as a Successor Beneficiary and would not be automatically subject to the 10-Year Rule (i.e., if they were able to qualify as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary, they could qualify to take advantage of the ‘stretch’ provision).

For scenario 3, Successor Beneficiaries who inherit from post-SECURE Act Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries are, like other Successor Beneficiaries, subject to the 10-Year Rule; however, unlike other Success Beneficiaries, they will not have their ‘own’ 10-Year timeframe. Instead, their distribution period is a continuation of the 10-Year period that started when the Successor Beneficiary inherited the account.

Although the SECURE Act may negatively impact some Successor Beneficiaries by limiting the time they are allowed to prolong their Required Minimum Distributions, some Successor Beneficiaries may actually be able to benefit from the Act’s changes. In some instances, the number of years a Successor Beneficiary may have to empty their inherited retirement account may be extended, while in other instances, they may simply have a similar amount of time, but more flexibility than was previously allowed prior to the passage of the SECURE Act.

For example, for a Designated Beneficiary who ‘stretched’ RMDs and lives for a long time yet still dies with a substantial account balance, their Successor Beneficiary may have been left with only a few short years to distribute the remaining assets had it been under pre-SECURE Act rules (as they would have been required to use the original beneficiary’s remaining Single Life Expectancy). However, the 10-Year Rule of the SECURE Act now allows these Successor Beneficiaries up to 10 full years to distribute their accounts.

Ultimately, the key point is that while most of the attention on the SECURE Act’s impact on retirement account rules has focused on Primary Beneficiaries, the reality is that Successor Beneficiaries are impacted by the SECURE Act changes as well. While Successor Beneficiaries who inherit accounts from beneficiaries taking RMDs using the ‘stretch’ provision will get the 10-Year Rule (from scratch), some Successor Beneficiaries (i.e., post-SECURE Act beneficiaries of Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries) will ‘only’ be able to step into the initial beneficiary’s shoes, and will have to empty the balance of the IRA by the end of the 10-year period established by the original 10-year rule (i.e., the Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary’s 10-year window). For both the original account beneficiary and their own named Successor Beneficiaries, the SECURE Act has created changes and potential opportunities that impact them both.

On December 20, 2019, the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act was signed into law by President Donald Trump. The law made a number of sweeping changes to the rules for retirement accounts, but the headline news, for many, was the Act’s elimination of the ‘stretch’ option for most non-spouse beneficiaries of inherited retirement accounts.

The SECURE Act’s changes to the post-death distribution rules go deeper than just one beneficiary level, though. Rather, there are significant impacts to both the initial beneficiaries of retirement accounts, as well as Successor Beneficiaries of the same accounts. Advisors must be aware of the rules for both in order to properly guide clients in the coming years.

The SECURE Act’s Changes To The Post-Death Distribution Rules For Designated Beneficiaries Of Retirement Accounts

Prior to the passage of the SECURE Act, the default rule for Designated Beneficiaries (living people, as well as qualifying See-Through Trusts) of a deceased individual’s retirement account was that such beneficiaries would be able to ‘stretch’ distributions over their life expectancy. This ‘Stretch’ provision allowed Designated Beneficiaries – and younger Designated Beneficiaries, in particular – to begin taking relatively small distributions, based on their life expectancy (as calculated using the IRS-provided Single Life Expectancy Table), from inherited retirement accounts beginning in the year after the owner’s death. And while the percentage necessary to withdraw each year under the ‘stretch’ method increases, ‘stretching’ an inherited retirement account often allowed it to continue to grow for many years, and to last for several decades or longer.

For instance, using the ‘stretch’ method, an IRA beneficiary turning 49 years old in the year of the IRA owner’s death needed to begin taking required minimum distributions the following year, in which they turn 50. Furthermore, the Single Life Expectancy Table factor for a 50-year-old is 34.2. Thus, such a beneficiary’s first required minimum distribution would be less than 3% (100 ÷ 34.2 equals 2.92%), and distributions from the account could be ‘stretched’ for as many as 34.2 years!

The SECURE Act, however, eliminated the ‘stretch’ option for most Non-Spouse Designated Beneficiaries. Instead of being able to ‘stretch’ distributions, such beneficiaries now generally fall into a new group of SECURE Act-created beneficiaries, known as Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, who are subject to a new 10-Year Rule that requires them to distribute the entirety of an inherited retirement account by the end of the 10th year following the year of the original account owner’s death.

The 10-Year Rule does provide Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries some flexibility, though, as there are no requirements other than emptying the account by the end of the 10th year after the year of the IRA owner’s death (i.e., no distributions of any amount are required in years one through nine after the IRA owner’s death, but voluntarily distributions of any amount are allowed, allowing the owner to make the choice of spreading out the distributions or simply waiting to liquidate the entire account balance in the 10th year).

Still, other than in the case of a much older Designated Beneficiary (with a Single Life Expectancy Table factor of less than 10), the 10-Year Rule compresses the amount of time over which a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary may spread distributions from their inherited retirement account, as compared to the ‘old’ lifetime Stretch rules.

The SECURE Act does, however, provide a limited exception to the changes to the post-death rules for Designated Beneficiaries. More specifically, the SECURE Act creates another new group of beneficiaries, known as Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, which includes spousal beneficiaries, the disabled and chronically ill, beneficiaries who are not more than 10 years younger than the decedent, and certain minor children, who are exempt from the 10-Year Rule as outlined above, and who may still utilize the ‘stretch’.

Certain See-Through Trusts drafted to benefit individuals who fall into one or more of the groups described above may qualify to be treated as Eligible Designated Beneficiaries as well. Generally, such trusts would have to be Conduit Trusts. However, Discretionary Trusts which meet the Applicable Multi-Beneficiary Trust requirements (also created by the SECURE Act) may also be treated as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary.

Successor Beneficiaries Are A Beneficiary’s Beneficiary

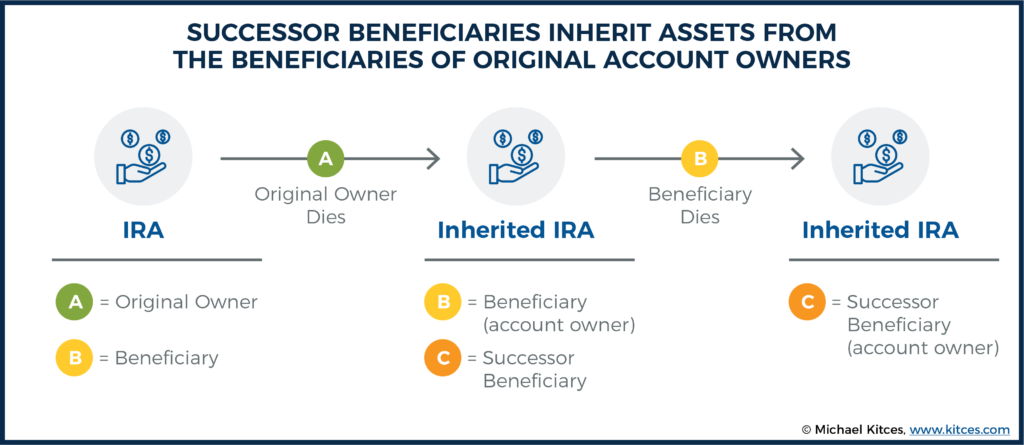

At its core, a Successor Beneficiary is simply the beneficiary of a previous beneficiary.

More specifically, when an individual inherits a retirement account from the original owner, they become a beneficiary. In many cases, the assets in the inherited retirement account will be completely distributed to that beneficiary prior to the beneficiary’s own death (in which case, there won’t be a Successor Beneficiary). In other cases, however, there are still funds remaining in the inherited retirement account at the time of the original beneficiary’s death.

Those assets don’t just disappear. They have to go somewhere!

And the person (or entity) to whom those assets pass is known as a Successor Beneficiary. They are, quite simply, the beneficiary’s own beneficiary.

Notably, since the passing of the SECURE Act, much attention has been placed on deciphering the new post-death distribution rules for Designated Beneficiaries (including both Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries and Eligible Designated Beneficiaries). Far less focus, however, has been placed on understanding what happens when a beneficiary in the post-SECURE Act world dies, and leaves money to their Successor Beneficiary.

This is certainly understandable, as the SECURE Act’s 10-Year Rule will undoubtedly reduce the number of such beneficiaries as compared to years past, when there was no limit to the length of time in which an account had to be liquidated. Nevertheless, whether it be from a pre-SECURE Act Designated Beneficiary ‘stretching’ distributions, a post-SECURE Act Eligible Designated Beneficiary ‘stretching’ distributions, or a post-SECURE Act Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary who dies prior to the end of the 10-Year Rule, a nontrivial number of Successor Beneficiaries will continue to inherit the remaining balance of retirement dollars from the original beneficiary… and will need guidance from their advisors as to how to timely distribute those assets.

Example #1: Jamie inherited an IRA from her father in 2003, having been named the original beneficiary by her father.

Upon inheriting the account, she set up an inherited IRA and named her daughter, Maxine, as the subsequent beneficiary of her inherited IRA, should something happen to Jamie before the account was fully distributed.

In March 2020, Jamie passed away, and Maxine inherited Jamie’s inherited IRA. Maxine, therefore, became the Successor Beneficiary of the account.

Nerd Note:

There is no special terminology for a subsequent beneficiary, beyond that of Successor Beneficiary. Thus, if a Successor Beneficiary dies, the individual (or entity) that inherits the Successor Beneficiaries inherited (inherited) IRA is also still simply called a Successor Beneficiary (not a Successor-Successor Beneficiary!).

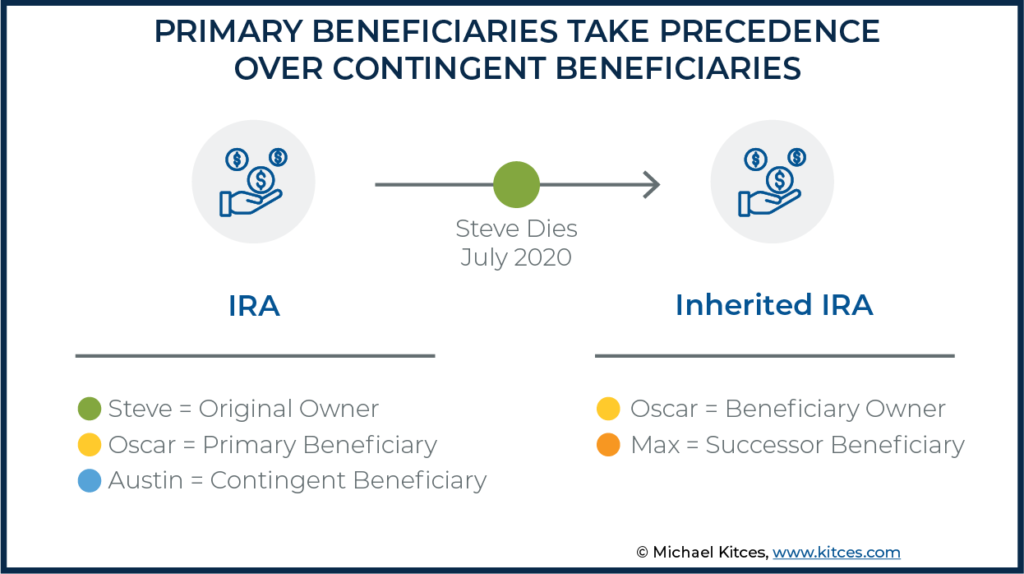

Critically, though, a Successor Beneficiary is not the same as a Contingent Beneficiary. A Contingent Beneficiary is an individual’s second-choice beneficiary if their first-in-line (primary) beneficiary predeceases them (or disclaims the asset, in which case the first-in-line beneficiary is treated as though they predeceased the owner).

If a retirement account owner’s Primary Beneficiary survives them and inherits their retirement account, the decedent-IRA-owner’s Contingent Beneficiary becomes meaningless. They are not entitled to any of the assets in the inherited retirement account, nor are they automatically in line to receive any remaining funds in the inherited account upon the Primary Beneficiary’s death.

The Primary Beneficiary, of course, may name the original decedent’s contingent beneficiary as their own Primary Beneficiary of the inherited account (which would make them a Successor Beneficiary upon inheritance), but there is actually no requirement for them to do so. Rather, they may choose whoever (or whatever) they’d like as their own Primary Beneficiary of the inherited account.

Or stated more simply, the Contingent beneficiary steps in for the Primary beneficiary (effectively becoming the new Primary beneficiary) if the original Primary dies before the account owner themselves. Whereas the Successor beneficiary steps in after the Primary beneficiary if the original account owner has already died, and the Primary beneficiary has already become ‘the’ beneficiary.

Example #2: Steve is the owner of an IRA and has named Oscar as their Primary Beneficiary, and Austin as their Contingent Beneficiary.

If Oscar were to die before Steve, then Austin as the Contingent Beneficiary would effectively become the new Primary beneficiary, to inherit the account when Steve passes away.

Alternatively, if Steve dies first, then Oscar inherits the account, and Austin no longer is on the list of Steve’s beneficiaries (as his role as Contingent beneficiary is now a moot point).

On the other hand, as Oscar inherits the account, he must subsequently set up an inherited IRA, and name his own Successor beneficiary to receive the account if Oscar now dies. Oscar names Max as the beneficiary of the inherited IRA.

Notably, this means that if Oscar dies prior to exhausting the funds in the inherited IRA, Austin will (still) not receive any of the remaining funds in the account (as the Contingent beneficiary is no longer relevant once Steve, the original account owner, has died), as the funds will pass to Max as the Successor Beneficiary (the newly named Primary Beneficiary of Oscar’s inherited IRA).

Rules For Successor Beneficiaries After The SECURE Act

The 10-Year Rule of the SECURE Act shortens the time period during which most post-SECURE Act non-spouse beneficiaries have to distribute assets from their inherited retirement account. So too does it shorten the time period during which most post-SECURE Act Successor Beneficiaries have to distribute the funds from their inherited (inherited) retirement accounts. But for a small subset of post-SECURE Act Successor Beneficiaries, the Act will actually extend the amount of time they have to distribute their inherited assets.

In analyzing the rules for Successor Beneficiaries in the post-SECURE Act world, there are three scenarios that must be considered for Successor Beneficiaries. They are as follows:

- Successor Beneficiaries of post-SECURE Act Eligible Designated Beneficiaries

- Successor Beneficiaries of pre-SECURE Act Designated Beneficiaries

- Successor Beneficiaries of post-SECURE Act Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries

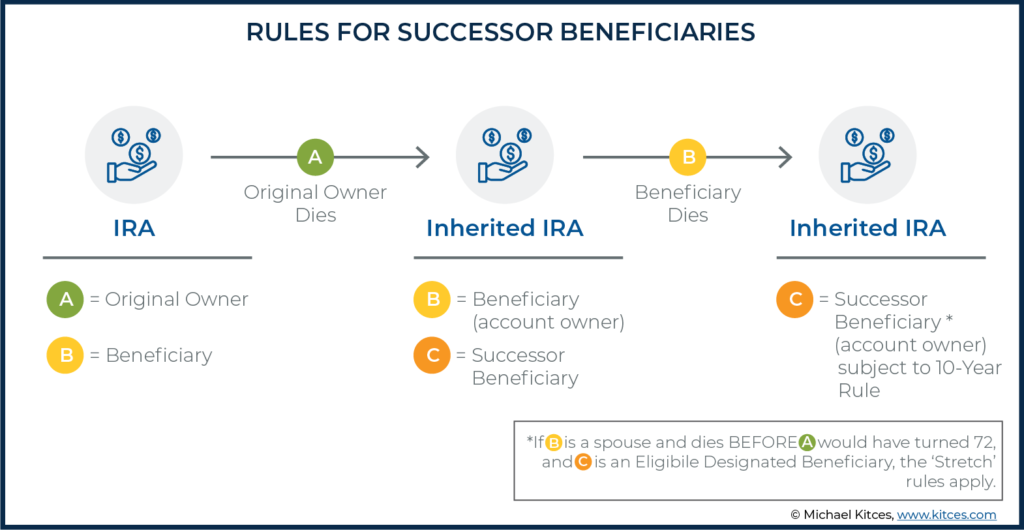

In scenarios 1 and 2, a Successor Beneficiary will generally (subject to an exception for certain Successor Beneficiaries discussed below) find themselves subject to the (full) 10-Year Rule. By contrast, in scenario 3, Successor Beneficiaries will find they can ‘only’ continue enjoying any time remaining in the original Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary’s 10-Year Rule.

Scenario #1: Successor Beneficiaries Of A Post-SECURE Act Eligible Designated Beneficiary

When analyzing the SECURE Act’s impact on Successor Beneficiaries, it makes sense to start by evaluating the impact on Successor Beneficiaries who inherit from a post-SECURE Act Eligible Designated Beneficiary (i.e., those beneficiaries who actually can still stretch the inherited retirement account even after the SECURE Act). In fairness, this is unlikely to be the situation for the majority of Successor Beneficiaries who inherit in 2020, and in the immediate years thereafter, as it requires:

1) The death of the original retirement account owner in 2020 or later;

2) The beneficiary of that account owner to be an Eligible Designated Beneficiary (which is a fairly limited group in and of itself); and

3) The death of the Eligible Designated Beneficiary before all the funds in the inherited retirement account have been distributed.

Nevertheless, the Act’s statutory language makes this the logical place to begin one’s analysis (the reason for which will become clearer, momentarily).

Specifically, the SECURE Act created new IRC Section 401(a)(9)(H)(iii), which states:

Rules upon death of eligible designated beneficiary.— If an eligible designated beneficiary dies before the portion of the employee’s interest to which this subparagraph applies is entirely distributed, the exception under clause (ii) shall not apply to any beneficiary of such eligible designated beneficiary and the remainder of such portion shall be distributed within 10 years after the death of such eligible designated beneficiary. [Emphasis added]

The reference to “clause (ii)” in the excerpt from the SECURE Act above refers to the section of the SECURE Act that creates Eligible Designated Beneficiaries. Thus, new IRC Section 401(a)(9)(H)(iii) essentially says that “any” Successor Beneficiary of an Eligible Designated Beneficiary will not, themselves, be treated as a clause (ii) Eligible Designation Beneficiary, and that Successor Beneficiaries should instead be treated as a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, subject to the SECURE Act’s 10-Year Rule.

Example #3: On February 1, 2020, Abbott, a 70-year-old individual, inherited an IRA from his brother, who is 78. As such, Abbott was an Eligible Designated Beneficiary, able to ‘stretch’ distributions over his life expectancy (as he was less than 10 years younger than his brother).

At some point, of course, Abbott, himself, will pass away. And when that happens, if there is any money still left in the inherited IRA, ‘stretch’ distributions will cease, and the next beneficiary (the Successor Beneficiary named by Abbott) will be subject to the 10-Year Rule. Notably, this is true whether Abbott lives 10 weeks after inheriting the IRA, or 10 years, or even more.

Furthermore, it’s important to emphasize that in the example above, it makes no difference who is named as the successor beneficiary. That person (or entity) will be subject to the SECURE Act’s 10-Year Rule. Put differently, it is not possible to be an Eligible Designated Beneficiary of an Eligible Designated Beneficiary… because “any beneficiary” of an eligible designated beneficiary must distribute the inherited assets “within 10 years after the death.”

Nor, for that matter, can a Successor Beneficiary continue taking distributions over the initial beneficiary’s remaining life expectancy, as was the case before the SECURE Act took effect.

The 10-Year Rule applies to Successor Beneficiaries. Period.

Well… sort of…

Exception For Eligible Designated Beneficiaries Of Spousal (Eligible Designated) Beneficiaries

Depending upon your reading of the Internal Revenue Code, there may actually be one exception to the no-Eligible-Designated-Beneficiary-of-an-Eligible-Designated-Beneficiary rule. In truth, it’s somewhat a matter of semantics.

More specifically, IRC Section 401(a)(9)(B)(iv)(II) states that “if the surviving spouse dies before the distributions to such spouse begin, this subparagraph shall be applied as if the surviving spouse were the employee.”

Thus, while a surviving spouse who chooses to remain a beneficiary (often because they are under the age of 59 ½ and want to continue to maintain penalty-free access to the inherited funds) is treated as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary under the SECURE Act for as long as they live, if they die before required minimum distributions ‘kick in’ on the inherited account (beginning in the year that the original decedent would have turned 72 for deaths occurring after the SECURE Act), IRC Section 401(a)(9)(B)(iv)(II) will treat them as though they were the owner of the account at the time of their passing.

Thus, at the instant such a ‘surviving’ spouse dies, they are essentially transformed from Eligible Designated Beneficiary to retirement account owner (and as a result, the no-Eligible-Designated-Beneficiary-of-an-Eligible-Designated-Beneficiary rule continues to ring true, as the next beneficiary is actually the first beneficiary… again!).

Accordingly, if a surviving spouse with an inherited IRA, 401(k), or other retirement account dies before the year in which the original post-SECURE-Act decedent would have been 72, they will be treated as though they were the original owner upon their death. This allows the surviving spouse’s beneficiary to be treated as the first beneficiary – and not as a Successor Beneficiary – which may in turn enable them to qualify as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary (assuming that they otherwise meet the qualifications to be treated as such).

Nerd Note:

To date, the IRS has provided little guidance on how to implement some of the rules created by the SECURE Act, and as a result, there remains a substantial amount of ambiguity surrounding various provisions. Case in point?

It is absolutely clear that a surviving spouse who remains the beneficiary of a retirement account will not have to take RMDs from the inherited account until the deceased spouse would have been 72 if that spouse died after the SECURE Act’s effective date. By contrast, if death occurred prior to the SECURE Act’s effective date (and the deceased spouse would not yet have reached age 70 ½ by the end of 2019), it is not clear whether a surviving spouse remaining as the beneficiary of a retirement account would be required to begin RMDs when the deceased spouse would have turned 70 ½, or whether they’d be able to wait until the deceased spouse would have been 72.

Example #4a: On March 1, 2020, Ann, age 45, inherited an IRA from her spouse of the same age. Given her age, Ann chose to remain a beneficiary of the inherited IRA to allow her penalty-free access to its funds.

Suppose now that Ann dies in 2030 at the age of 55, and leaves her IRA to her 53-year-old younger sister, Nancy.

Since Ann died before her deceased spouse would have turned 72, the exception under IRC Section 401(a)(9)(B)(iv)(II) will apply, and Ann will be treated as though she were the original owner upon her death. Thus, Nancy will be treated as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary (because she is less than 10 years younger than Ann) and will be able to ‘stretch’ distributions over her life expectancy.

Nancy will not be considered a Successor Beneficiary, and will not be subject to the SECURE Act’s 10-Year Rule.

By contrast, if the ‘surviving’ spouse dies in the year the original decedent would have been 72 or later, this exception no longer applies, and the Eligible Designated Beneficiary-surviving-spouse will continue to be treated as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary upon their death. Thus, the ‘surviving’ spouse’s beneficiary will be a Successor Beneficiary, and definitively subject to the 10-Year Rule.

Example #4b: On April 20, 2020, Helena, age 48, inherited an IRA from her 65-year-old spouse. Given Helena’s age, she chose to remain a beneficiary of the inherited IRA to allow her penalty-free access to its funds.

Suppose now that Helena dies in 2030, at the age of 58, and leaves her inherited IRA to her 53-year-old sister, Ava.

Since Helena inherited her IRA in 2020, when her spouse was 65, by 2030, at Helena’s death, her deceased spouse would have been 75 years old. Therefore, since Helena’s deceased spouse would have been older than 72, Required Minimum Distributions from the inherited IRA would have already begun, and the exception under IRC Section 401(a)(9)(B)(iv)(II) would no longer apply.

Thus, despite the fact that Ava is less than 10 years younger than Helena, she would not be treated as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary. Rather, she would be considered the Successor Beneficiary of an Eligible Designated Beneficiary and is ‘automatically’ subject to the SECURE Act’s 10-Year Rule.

Scenario #2: Successor Beneficiaries Of Pre-SECURE Act Designated Beneficiaries

The most common way an individual is likely to become a Successor Beneficiary – at least for the foreseeable future – is by becoming the Successor Beneficiary of a retirement account that was first inherited by a Designated Beneficiary prior to the SECURE Act’s effective date. As given the recent enactment of the legislation, there are simply more Designated Beneficiaries around today who inherited retirement accounts prior to the SECURE Act than there are of those who inherited after the SECURE Act’s effective date (January 1, 2020 for most retirement accounts).

The rules for Successor Beneficiaries of pre-SECURE Act Designated Beneficiaries will be rather straightforward for advisors who understand the rules for Successor Beneficiaries of post-SECURE Act Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (as discussed above in Scenario #1).] That’s because the rules are essentially the same!

Subject to the same ‘exception’ for surviving spouses as discussed above, any Successor Beneficiary inheriting an IRA, 401(k), or other retirement account from an individual who died before the SECURE Act’s effective date will find themselves subject to the SECURE Act’s 10-Year Rule.

Nerd Note:

Prior to the SECURE Act, when a Designated Beneficiary stretching distributions died, the Successor Beneficiary was able to, in essence, step into the Designated Beneficiary’s shoes, and continue taking distributions calculated using the original ‘stretch’ schedule. That’s no longer the case. In short, the SECURE Act treats a pre-SECURE Act Designated Beneficiary as though they are an Eligible Designated Beneficiary.

More specifically, Section 401(b)(5) of the SECURE Act states:

5) Exception for certain beneficiaries.--

(A) In general.--If an employee dies before the effective date, then, in applying the amendments made by this section to such employee’s designated beneficiary who dies after such date--

(i) such amendments shall apply to any beneficiary of such designated beneficiary; and

(ii) the designated beneficiary shall be treated as an eligible designated beneficiary for purposes of applying section 401(a)(9)(H)(ii) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 (as in effect after such amendments).” [emphasis added]

Simplifying The Successor Beneficiary Rules For Beneficiaries Of ‘Stretch Beneficiaries’

Since the rules for Successor Beneficiaries of pre-SECURE Act Designated Beneficiaries and post-SECURE Act Eligible Designated Beneficiaries are the same, it’s fair to simplify things and discuss the rules and planning for such beneficiaries together.

As described above, these beneficiaries are generally subject to the SECURE Act’s 10-Year Rule, and the only exception, in either case, is when a ‘surviving’ spouse beneficiary dies before the original decedent-spouse would have reached the year in which they turn 72.

Notably, surviving spouses who remain a beneficiary of a deceased spouse’s inherited retirement account do not have to take Required Minimum Distributions from the inherited account until the same time… the year in which the deceased spouse would have turned 72. Thus, the Successor Beneficiary rules can be simplified to say that any beneficiary (including a surviving spouse) of a previous beneficiary who was taking RMDs using the ‘stretch’ is subject to the SECURE Act’s 10-Year Rule.

Put differently, the Successor Beneficiary of a ‘Stretch Beneficiary’ will always be subject to the 10-Year Rule.

Scenario #3: Successor Beneficiaries of post-SECURE Act Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries

The third and final scenario for a Successor Beneficiary is one in which they inherit from a post-SECURE Act Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary. In such situations, the Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary would have been subject to the SECURE Act’s 10-Year Rule upon inheriting the retirement account.

Not surprisingly, a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary’s beneficiary (the Successor Beneficiary) cannot be an Eligible Designated Beneficiary. Does this mean that the Successor Beneficiary gets their own new 10-Year Rule?

Unfortunately, the answer is “no.” Rather, the Successor Beneficiary of a post SECURE Act Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary simply steps into the original (Non-Eligible Designated) beneficiary’s shoes. Which means the best they can do is to fill the original Primary Beneficiary’s 10-Year Rule (and they don’t even get to reset with their own new 10-Year Rule!).

Example #5: On May 1, 2020, an IRA owner died, leaving his account to his adult, healthy son, Joey. Joey is, therefore, a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary, subject to the SECURE Act 10-Year Rule. Accordingly, he must empty the inherited retirement account by the end of 2030.

Suppose, however, that Joey only lives for another four years, and dies in 2024. At that time, Joey’s Successor Beneficiary will step into his shoes. Thus, Joey’s beneficiary does not get a new 10-Year Rule running until 2034. Instead, Joey’s beneficiary would ‘just’ have flexibility over how much or (or how little) to distribute from the inherited retirement account for the six tax years beginning in 2024, and ending in 2029.

Either way, in 2030, any amounts remaining in the account would have to be distributed by year-end, as that would be the end of the 10th year following the year of the original account owner’s death.

The SECURE Act Extends The Distribution Period And Enhances Flexibility For Some Successor Beneficiaries

While the SECURE Act negatively impacts some Successor Beneficiaries, interestingly, it also will improve things for other Successor Beneficiaries, by either extending the number of years they have to empty their inherited (inherited) retirement accounts and/or by providing them with more flexibility than was available under the pre-SECURE Act rules.

Notably, under the pre-SECURE Act rules, a Successor Beneficiary of a ‘Stretch Beneficiary’ would continue taking ‘stretch’ distributions using the original beneficiary’s remaining Single Life Expectancy. Thus, if the original beneficiary of a retirement account lived long enough, or inherited the account at an advanced (enough) age, the Successor Beneficiary could have been left with fewer than 10 years to distribute the remaining assets. But now, thanks to the SECURE Act, such beneficiaries will benefit from the 10-Year Rule.

Example #6: In 2005, Monica, age 67 at the time, inherited an IRA from her mother. As such, Monica began taking ‘stretch’ RMDs from her inherited IRA in 2006 using the Single Life Expectancy Table factor for a 68-year-old of 18.6.

Since 2006, Monica has continued to take RMDs from the inherited IRA using the ‘stretch’ by reducing the factor by one each year. Accordingly, in January 2020, Monica (now aged 82) took her 2020 inherited IRA RMD using a factor of 18.6 - 14 = 4.6.

Now, suppose that Monica passes away in November 2020 with $200,000 remaining in the inherited IRA. Under the pre-SECURE Act rules, Monica’s Successor Beneficiary (whoever, or whatever, it is) would be ‘stuck’ using Monica’s remaining life expectancy to calculate future distributions. Thus, the Successor Beneficiary would have needed to take an RMD in 2021 using a factor of 4.6 - 1 = 3.6, producing an RMD of $200,000 ÷ 3.6 = $55,555.55.

By contrast, under the SECURE Act rules, Monica’s Successor Beneficiary is now automatically subject to the 10-Year Rule. Thus, the successor beneficiary will have 10 years – or roughly 3 times as many years – over which to spread distributions, if desired, in addition to greater flexibility over the timing of distributions (as there would be no RMD until 2030, the 10th year after Monica’s death, as opposed to drawing annually for the next 3.6 years under Monica’s original stretch).

Planning For Successor Beneficiaries Of Stretch Beneficiaries

As outlined earlier in this article, the majority of non-spouse Designated Beneficiaries inheriting after the SECURE Act’s effective date will be Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, and subject to the SECURE Act’s 10-Year Rule. This is the exact same rule that will apply to any Successor Beneficiary of a ‘Stretch Beneficiary’. Accordingly, the planning strategies for all such individuals are the same.

For individuals subject to the 10-Year Rule, that planning essentially comes down to one thing: deciding when, during the period of time covered by the 10-Year Rule, it makes sense to distribute the inherited retirement account assets. Thankfully, the 10-Year Rule provides a significant amount of flexibility, enabling beneficiaries to engage in a variety of planning strategies.

For example, beneficiaries of Roth accounts subject to the 10-Year Rule should generally wait until the end of the 10th year after the year of death to distribute any and all of the inherited assets, as it will allow for the maximum amount of tax-free compounding.

Alternatively, individuals who inherit taxable retirement accounts will often benefit from spreading distributions out over a number of years in order to minimize the chances of being pushed into a (much) higher tax bracket. And in still other instances, it will make sense for individuals to target large distributions over a small number of years, if those years happen to be years in which income is much lower, or deductions much higher, than in other years during the 10-year window during which the inherited retirement account must be emptied.

The SECURE Act made massive changes to the post-death distribution rules governing retirement accounts. The majority of the attention surrounding those changes has been focused on its elimination of the ‘stretch’ provision for most non-spouse Designated Beneficiaries, but the changes also have a substantial impact on the beneficiaries of beneficiaries – the Successor Beneficiaries – as well.

With the Baby Boomer generation continuing to age, it is likely that the number of Successor Beneficiaries will continue to rise in the coming years. Thus, advisors must have a sound understanding of the rules that apply in such situations in order to properly guide clients.

Thankfully, the rules for Successor Beneficiaries in the post-SECURE Act world are pretty simple in most instances. Any Successor Beneficiary of a (pre- or post-SECURE Act) beneficiary taking required minimum distributions using the ‘stretch’ method will be subject to the 10-Year Rule. Which, unfortunately, will usually be shorter than the prior Stretch beneficiary’s remaining distribution period… though for some older beneficiaries, the new 10-Year Rule can still be more favorable.

By contrast, any Successor Beneficiary of a Post-SECURE Act beneficiary subject to the 10-Year Rule will step into the post-SECURE Act beneficiary’s shoes and will have to empty the account by the end of the 10th year following the original account owner’s death (rather than receiving their own new 10-Year Rule).

Ultimately, the key point is that the SECURE Act changes things for both ‘regular’ original beneficiaries of retirement accounts, and the beneficiaries they name as their Successor Beneficiaries. And both types of beneficiaries need to be aware of the rules in order to avoid penalties and minimize the impact of taxes on any distributions.

CFP “Fiduciary” in Boca Raton having problems!! It’s now been 8 months since the passing of the SECURE ACT and there is still disarray in the qualified “SPIA” markets to such a degree, that pre-purchase illustrations for post SECURE ACT contracts of how contracts are to supposed to operate relative to the Beneficiary(ies) and also their Beneficiary(ies), are not reliable. For post-Secure Act issue contracts, the entire carrier market has refused to address how such contracts might be altered when Annuitants die when the contract falls outside SECURE Act compliance. And Spousal beneficiaries, who are not within 10 years of age, have to be married at TIME OF DEATH. If they aren’t, they will not be eligible for spousal treatment. So, another SPIA contract problem the cariers refuse to address!!!!

In 2020, a son inherits an Inherited IRA and Inherited Roth IRA from his mom who originally inherited them 10+ years ago from her sister. From what I read here these 2nd Generation Inherited IRAs are subject to the new 10 year distribution rule regardless if they are first/second/third generation. Furthermore, the son also inherited a 1st Generation IRA and Roth from his mom. Therefore, the underlying question is given that both the 1st and 2nd Gen Inherited IRAs are subject to the same 10 year rule can we consolidate the them into one Inherited IRA and one Inherited Roth IRA for the beneficiary. This would result in 2 accounts instead of 4 and simplify ongoing administration. Mom passed in May 2020 and Aunt passed 10 plus years ago. Thanks for any insight you have.

Side note: We have a custodian that has already allowed the commingling of these accounts (but they are passing on confirming IRS compliance). Trying to determine if we should reclaim the assets back to the contra firm and set up separate accounts instead.

What is the source for the conclusion in scenario #3 that the successor designated beneficiary (of a non-EDB who passes after 2020) does not get their own 10-year payout beginning at the death of the non-EDB, but instead must “step into the shoes” so to speak, of the non-EDB’s 10-year payout? I cannot find a reference to this conclusion here or anywhere else. Thank you!

Regarding the 10-year timing, what is their interpretation of 10 years? For example, the language is reading “within 10 years after death” but what if the death occurs July 1, 2020. Does it need to be emptied by the end of 2029? If so, it’s like 9.5 years. Or is it the year after the year of death, thus making it 12-31-2030 that it needs to be empty (which essentially makes it 10.5 years to empty it)?

I’m equally confused on the timing. MGP is showing an IRA Inherited in 2020 would need to be distributed in 2029. Fidelity and this article state 2030… It’s very confusing!

I’m still confused! My wife inherited an IRA from her sister in 2017.

My wife passed in November 2020 and I am the sole beneficiary. We had been taking RMD’s based on my wife’s age (69), I am older. I was under the impression I would continue RMD’s based on my wife’s age (step into her shoes?)

Am I wrong? Is this under the old rules?

How old would your SIL have been at your wife’s DoD? Sounds like, if under 70.5, you (as a successor bene) would be the exception and not subject to 10-year rule.

I’m receiving conflicting information regarding the timing of distributions. If a non-eligible beneficiary inherits – for example, in May 2020. Do they have until 12/31/2030? Or is it 2029? MGP is showing the distribution to be in the 10th year in 2029. Fidelity says 2030 and I believe this article states 2030. Can anyone help confirm this for me? Thank you!!!

What happens if parent passes away in 2019, Son 1 inherits the IRA, then Son 1 dies in 2020 and Son 2 inherits Son 1’s inherited IRA? Is it still eligible to be a stretch IRA

This is very helpful but leaves one situation ambiguous: what happens to successor beneficiaries when both the original owner AND first beneficiary died before 2020?

This would seem to fall under scenario 2 – SUCCESSOR BENEFICIARIES OF PRE-SECURE ACT DESIGNATED BENEFICIARIES – which suggests that “the Successor Beneficiary of a ‘Stretch Beneficiary’ will always be subject to the 10-Year Rule.”

However, I wonder if there is an unstated assumption here that your article is only addressing first beneficiaries who died in 2020 or beyond, after the SECURE act took effect. I have seen others cite this article to argue that, for example, if a stretch beneficiary died in 2018, the successor beneficiary would need to switch from RMDs to the 10-year rule. Is that correct?

That would also imply that a successor beneficiary of a stretch beneficiary who died in 2008 would have to apply the 10-year rule even though more than ten years have already passed since they inherited the IRA.

It would be very helpful to add a clarification to this point to your article to make it unambiguous whether Scenario 2 is just considering beneficiary deaths post-2019 or whether it includes pre-SECURE-act beneficiary deaths as well.

My mother inherited an IRA from her father – post SECURE Act. At the time it was advantageous to defer distributions to later in the 10 year period and no distributions have been taken to-date. Recently, due to a serious illness my mother is now disabled. Can she now use the SECURE act distribution method for disabled individuals (or is she locked into the 10 year period). Thank you.