Executive Summary

The “Paradox of Skill” is the recognition that as the average skill level of a group increases, it actually becomes harder and harder for superstars to occur; as the skill level rises, the variability around the group average declines. This phenomenon helps to explain why despite the improvement in baseball players, no one has hit over .400 since Ted Williams did it 75 years ago, and also provides insight on why it’s getting harder and harder to find “good” active investment managers. Because the whole field has gotten so much better, it’s actually become incredibly difficult to stand out from the (already excellent) pack.

As a result, a growing base of data suggests that the amount of available alpha is shrinking, a combination of both the paradox of skill itself, and the mere fact that more and more investment research is revealing previously unknown investment factors that, once known, can no longer be exploited the way they were in the past.

Yet despite this trend, a number of known investment opportunities have continued to persist, even though they’re widely known. For instance, it’s long since been documented that small cap outperforms large cap, that value generates a long term premium over growth, and that stocks exhibit momentum effects. But for all the research showing these outperformance opportunities to be available, investors fail to invest sufficiently to fully take advantage of them.

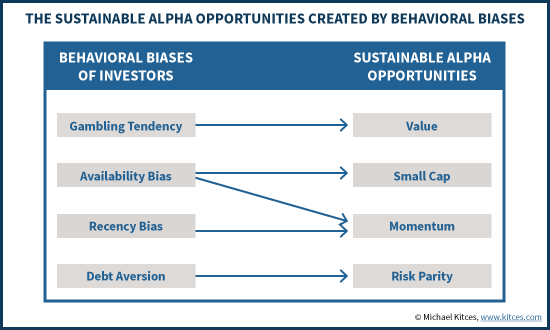

The gap, however, may be at least partially explained by the growing field of behavioral finance, and research that shows all the ways that we fail to invest “rationally” despite having all the available information (or without bothering to get it in the first place). And in point of fact, many of the most popular – and persistent – alpha opportunities, from small caps to value to momentum, are actually well-explained by common behavioral biases (including the availability, familiarity, and recency biases) that are hard-wired into our brains. Which helps to explain why they’re persistent – because their very nature is the tendency to impact our investment decisions, even when we “should” know better.

Of course, the caveat is that “sustainable alpha” opportunities created by persistent behavioral biases may be the hardest to exploit, precisely because those behavioral biases impact us as well – both in the investment decisions we make, and as advisors, the investment decisions we must justify to clients (who themselves have the same biases). Or viewed another way, it may be the persistent challenge and “risk” of trying to buck the behavioral trends that generates the risk premium associated with sustainable alpha in the first place!

The Paradox of Skill and The Incredible Shrinking Alpha

One of the fundamental challenges of today’s investing landscape is that there are a lot of smart people involved, and they have better tools than ever.

While one might think that smarter people with better tools would lead to more superstars, though, the reality – as first articulated by Michael Mauboussin in his book “The Success Equation” – is that a “Paradox of Skill” emerges: the better the average talent pool, the harder it is for standout winners who persistently outperform the rest. Because it’s hard to be that much smarter and better than everyone else, when the others are also very smart people with similarly quality tools.

Consequently, even as our capabilities to identify good investment opportunities gets better, the pool of available alpha appears to be shrinking – as articulated most eloquently by Larry Swedroe and Andrew Berkin in their 2015 book “The Incredible Shrinking Alpha”. The greater the shift of investing away from individuals and over to institutions (in the 1940s households held 90% of US corporate equity, and now it’s down to 20%), the fewer “investing mistakes” leading to market mispricings (alpha opportunities) there are on the table, and the more institutions there are trying to carve up the same fixed alpha pie (resulting in each getting an ever-smaller share).

In the logical extreme, some have suggested that eventually available alpha will go all the way down to zero – or at least to an imperceptibly low level that virtually no investor will be able to effectively capitalize on the small and very short term pricing discrepancies that emerge. Simply put, with so many investors competing at the same time with so much capital, it’s getting almost impossible to “see” an investment opportunity by having a better grasp of the information than everyone else (and of course, it’s still illegal to possess insider information that no one else has).

How Behavioral Biases Limit Market Efficiency

Notwithstanding the steady trend of shrinking alpha, as the capabilities and average skill level of investors rises, it’s not entirely clear that alpha can go all the way to zero. Because such a path presumes that all alpha is derived by simply better using available information than everyone else, and ignores the fact that a material number of investors aren’t making their investment decisions based solely on information (alone) in the first place.

After all, one of the “hottest” areas in finance in recent years has been research on behavioral finance, and a study of all the various ways that we do not invest rationally. As just a brief list of our problematic tendencies, we tend to…

- Exhibit a “recency bias”, where we overweight what happened recently and extrapolate it into the future (e.g., since markets are rallying, they’re going to continue to rally, and I should buy more!).

- Show an “availability bias”, making us more willing to invest into stocks we can readily recall (e.g., since Apple products are popular, we presume Apple must be a good stock to invest in…even without ever actually look at the underlying investment fundamentals).

- Perceive less risk in something we have familiarity with (thus helping to explain why so many are so comfortable keeping concentrated positions in their employer – because it feels like a known quantity that is “safe”, even if the employee has no actual access to special information that markets don’t!)

- Pursue gambles that have significant upside potential, despite their improbable outcome (which explains why we continue to buy lottery tickets with a highly negative expected value)

- Exhibit a significant aversion to losses and debt

- Move with the herd, showing a strong bias to do what everyone else is doing, and avoid the risk that comes with being singled out (especially if there’s a bad outcome and someone needs to be blamed)

All of these behavioral biases (along with many more not listed here) mean that when we make investment decisions, we may do so in a manner that contradicts the available information (or at the least, is done without fully assessing the information that is available). In other words, the research on behavioral finance suggests that there are a material number of investors who are not playing along with the “shrinking alpha” dynamic, because they’re not actually investing consistent with the available information in the first place.

Behavioral Biases Lead To Sustainable Alpha

The significance of behavioral biases leading to “irrational” investing – trading in ways that are not consistent with available information and investment fundamentals alone – is that it not only creates the potential for the mispricing of assets, but that it can result in persistent investment opportunities as long as the behavior itself persists. And in this context, persistence appears quite likely, given that these are investment “mistakes” driven by the brains are hard wired!

In other words, the idea that available alpha is shrinking as investors become more skilled and get better tools presumes that those investors are carving up an ever-shrinking pie of available alpha as markets more efficiently price in the available information. But in a world where mispricings are created at least in part due to behavioral biases that are simply part of our human nature, then no amount of information and expertise can make them entirely disappear.

In fact, the persistence of behavioral biases helps to explain why many risk premia and investment “factors” continue to persist, even long after they’re known to exist.

For instance, the small cap premium (that small cap stocks outperform large caps in the long run) arguably should not exist, once everyone knows that it exists and anticipates in advance that they’ll be fully rewarded for any short-term risk they take. However, the availability bias and the familiarity bias helps to explain why the small cap premium persists. Because people who are looking to invest are more likely to invest in stocks they have heard of, with companies they are familiar with. For instance, if an investor wants to buy a tech stock, they’re more likely to think of Apple or Google or Amazon, than a small cap company they’ve never heard of (which means the small cap stocks get less buying demand than they “should”). Even for an investment manager, there is a similar dynamic; as professional, you’re not as likely to get fired if you bought Apple or Google and it went down, compared to losing money in a small cap tech company that was perhaps more promising but no one had ever heard of previously.

Similarly, the value premium (that value stocks tend to outperform growth stocks in the long run), is another opportunity for outperformance that “shouldn’t” exist, given how well it’s been documented and that everyone “knows” it now. Yet from the perspective of our behavioral tendencies towards gambling – that growth is exciting and has ‘unlimited’ upside, while value is boring and unexciting and doesn’t stir our animal tendencies – it’s not difficult to see why investors would keep buying high-flying growth stocks even after they’ve been shown to average out with lower returns. Again, we also persistently buy lottery tickets, despite the fact that they, too, have a negative expected value over time.

Continuing this theme, it’s also easy to see why a persistent momentum effect exists. Because the recency bias leads us to persistently overweight the recent trend of the market, and assume it will continue. Or viewed another way, if our brains are hard-wired to assume that recent market trends will persist, we invest that way (continuing to pile dollars in), and it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, even if there’s no rational basis for it to begin with. Thus leading to John Maynard Keynes famous observation, “the markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent”.

And the impact of behavioral biases on investment opportunities isn’t exclusive to the Fama & French three-factor model (or Carhart’s four-factor model with momentum). For instance, the somewhat controversial risk parity strategy also has a behavioral underpinning: as Cliff Asness of AQR notes, most investors have a natural aversion to leverage (i.e., debt), and the aversion to leverage causes an under-investment in risk parity strategies that are mathematically more efficient but psychologically/behaviorally unappealing.

What all of this suggests is that even as some forms of available alpha are shrinking, and active managers continue to struggle, that the end game is not a world where the opportunity for alpha goes to zero. Instead, the existence of behavioral biases means that at least some firms of alpha can persist, even after they’re known and exploitable, but that alpha opportunity will only be sustainable if it is in fact predicated on a behavioral bias. If the alpha is based on expert information alone, the investor will inevitably be “outforcasted” by an increasingly sophisticated competition.

Of course, the caveat to recognizing that the most sustainable alpha opportunities are the behaviorally-derived ones is that they will also be the hardest ones for other human beings to take advantage of, for the very same reason. Whether it’s succumbing to the very biases that create the opportunities, or simply trying to move against the herd – and as an advisor, risk being fired by most of your clients, even if you’re right in the long run – behaviorally-driven alpha is arguably one of the riskiest forms of alpha to try to capture. Which, perhaps, explains exactly why it provides a persistent risk premium in the first place, even when it’s known to all!

So what do you think? Do behavioral biases create sustainable alpha? Can that alpha be captured in a profitable manner? Does trying to capture behaviorally-driven alpha put advisors at risk of being fired by clients? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!