Executive Summary

Tax-loss harvesting – i.e., selling investments at a loss to capture a tax deduction while re-investing the proceeds to maintain market exposure – is a popular strategy for financial advisors to increase their clients’ after-tax investment returns. For many, however, tax-loss harvesting remains somewhat more of an art than a science: Because the value of harvesting losses is so dependent on an individual’s own tax situation, there is no single strategy that can be implemented across an entire, diverse client base. And to complicate things further, when it is decided to go ahead with tax-loss harvesting, there are numerous considerations involved to ensure the strategy is carried out correctly and avoids running afoul of the IRS’s wash sale rules (which could disallow losses and negate the value of the strategy altogether).

But because tax-loss harvesting can be so valuable in certain situations, having a framework for deciding which clients could be good candidates for tax-loss harvesting and a process for executing the strategy properly can be beneficial for advisors. And given the challenges of scaling the strategy across dozens or even hundreds of clients, a key consideration when developing these best practices should be how well they can be systematized and repeated whenever the advisor reviews client accounts for tax-loss harvesting opportunities – a factor which can be aided with technology, including software tools that many advisors already use regularly.

For example, advisors who use a Customer Relationship Management (CRM) tool may be able to use that tool to narrow down the list of clients to those who are good tax-loss-harvesting candidates, such as those in higher tax brackets (who are likelier to realize more value from deducting capital losses). From there, the advisor’s financial planning software may be able to model the client’s future tax rate when the investment is ultimately sold, allowing the advisor to estimate the long-term value of harvesting the loss today. Finally, many software tools for trading and rebalancing may incorporate tools for tax-loss harvesting, such as checking for potential wash sale violations and allowing the advisor to designate replacement securities. With these three tools (i.e., the advisor’s CRM, planning software that models future tax scenarios, and trading and rebalancing tools), advisors can build a systematic start-to-finish process for tax-loss harvesting – and because all three are already core parts of many advisors’ existing technology stack, doing so might require no additional investment in technology!

The key point, however, is that – like many tax planning strategies – tax-loss harvesting requires at least some individual attention to each client’s tax situation to ensure it is the right strategy for that client. Additionally, there are many considerations both in deciding when to harvest losses and in executing the strategy, which makes it all the more important to have a repeatable process to ensure that nothing gets missed.

At a minimum, advisors can consider using a standardized tax-loss-harvesting checklist to reduce the likelihood of overlooking any important information. And because there is often pressure to act fast when markets are down and when tax-loss harvesting opportunities present themselves, having a well thought-out framework for harvesting losses can help advisors focus more of their attention on the clients who will get the most value from it (and fully deliver on that value in the end!).

Many financial advisors incorporate tax-loss harvesting into their portfolio management as a way, at least in theory, to boost their clients’ after-tax investment returns by lowering their tax bill when opportunities come along to sell assets at a loss and to use those capital losses to offset taxable gains.

But tax-loss harvesting is more than just a technique for portfolio management; rather, it is a tax-planning strategy that requires consideration of the investor’s broader tax situation. For financial advisors, then, the value of tax-loss harvesting can be minimal – or even negative! – for clients if the advisor doesn’t take everything into account. And even when it is a good idea to harvest losses, a mistake in execution could result in those losses being disallowed by the IRS’s wash sale rules.

Consequently, it’s important for advisors to have a framework for the two main steps of tax-loss harvesting:

- Deciding when (and when not) to tax-loss harvest; and

- Carrying out the process when the advisor does decide to harvest losses.

Furthermore, repeating these steps across dozens or hundreds of clients requires a way to systematize the process to ensure that all of the important considerations are accounted for without bogging down all of the advisor’s resources.

Which means that, for advisors who tax-loss harvest for their clients, having a basic set of best practices to follow, along with a framework for carrying them out, can be very valuable.

Step 1: Deciding When Tax-Loss Harvesting Is A Good Idea

Before getting into the details of implementing a tax-loss harvesting strategy, it’s beneficial to first take a step back and consider whether it is even a good idea to harvest losses. Because while many clients may have unrealized losses in their portfolios (particularly during a year in which markets are broadly down), they may not all be good candidates for tax-loss harvesting – and for some, harvesting losses now may even turn out negatively for them in the long run.

Deducting Losses Against Capital Gains Vs Ordinary Income

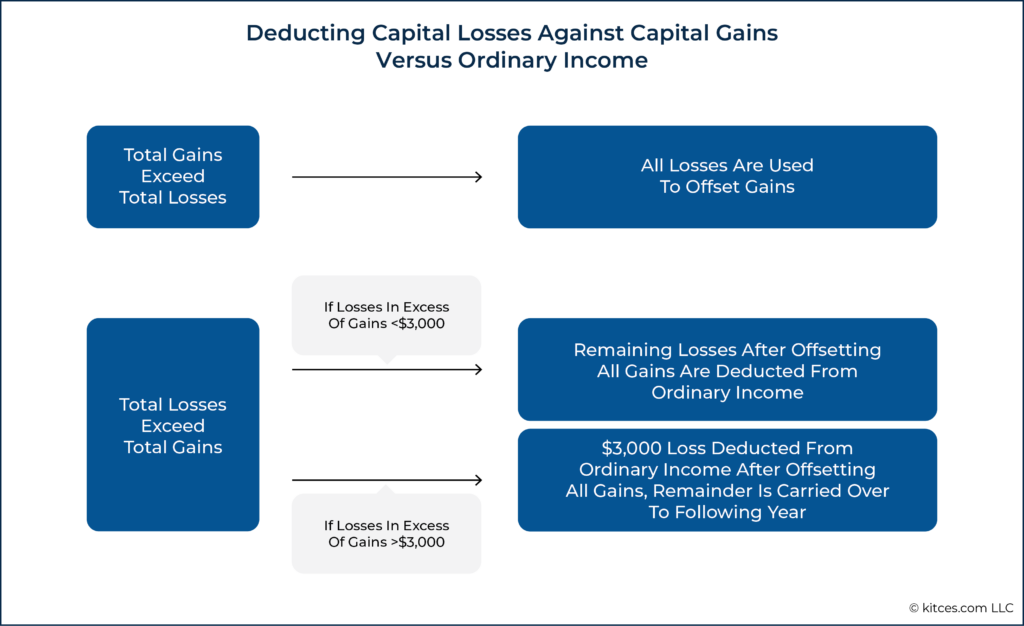

The first consideration could be whether there are capital gains elsewhere in the portfolio that would (or could) be offset by harvesting the loss. In general, capital losses can only be deducted to the extent of the taxpayer’s capital gains in the same year, with any unused losses being carried over to the next year. The exception to this rule is that, when net losses exceed net gains, up to $3,000 of losses can be deducted against the taxpayer’s ordinary income each year.

In many cases, it could make sense to harvest a loss if it can be deducted against ordinary income. But when there are more than $3,000 in losses used to offset ordinary income, then the remaining excess losses are carried over to future years. Which means the taxpayer must wait to capture some of the tax deduction from realizing the remaining loss – either until there are capital gains for the carryover losses to offset, or until the annual $3,000 deduction against ordinary income eventually ‘uses up’ the carryover loss. And in the case of large losses of tens of thousands of dollars or more, the taxpayer could go years between when they realize the loss and when they finally receive the tax deduction for doing so.

While it might make intuitive sense to ‘bank’ the loss when there are no gains to offset it in the current year (with the assumption that the carried-over loss will come in handy later on), there are cases where that strategy could backfire. Because any available carryover losses must be used to offset capital gains, having carryover losses could become a hindrance in situations where a taxpayer might actually want to realize capital gains without offsetting losses, such as in a temporarily low-income year where they find themselves in the 0% tax bracket.

Example 1: Sasha is an investor who has realized $100,000 of capital losses this year and has reinvested the proceeds into similar investments. She does not realize any capital gains that the loss can be used to offset in the current year.

However, in each of the first five years after harvesting the loss, she deducts $3,000 against her ordinary income and carries over the remaining loss to the next year, leaving her with $100,000 – ($3,000 × 5) = $85,000 in carryover losses after the fifth year.

In the sixth year after harvesting the loss, Sasha decides to take a year-long, unpaid sabbatical from her job, putting Sasha in the 0% capital gains tax bracket. While it would be appealing to use her temporarily low tax rates to realize capital gains in her portfolio, she would first need to realize $85,000 of gains just to ‘use up’ her existing carryover losses before she could realize any net gains to be taxed at 0%.

As the example above illustrates, when there aren’t enough capital gains to offset harvested losses, it’s important to weigh the possible downsides of carrying over losses into future years where they could impact other tax planning goals.

There are additional downsides to carrying over losses. One risk is that, if the taxpayer dies before all carryover losses are used up, the opportunity to use the remaining losses will also be lost upon the taxpayer’s death. Another risk is that carryover losses can potentially reduce how long taxes on gains can be deferred, along with the compounded growth associated with tax-deferred growth. This is because the benefits of tax-loss harvesting don’t start until the taxpayer actually deducts the loss, so having carryover losses that delay the deduction can sacrifice potential compound growth that could be achieved if the loss were deducted earlier.

One of the first indicators that an investor is a good candidate for tax-loss harvesting, then, is when they have (or will have) taxable capital gains that could be offset by losses. Common sources for capital gains could be withdrawals from the portfolio or trades made to rebalance the portfolio, but it’s also possible for capital gains to exist outside of the portfolio – such as taxable gains from the sale of real estate or a business. For clients in either of those scenarios, it might make sense to find losses to harvest when possible (particularly if a real estate or business sale would create enough of a taxable gain to temporarily bump the client into a higher capital gains tax bracket).

Tax Deferral Vs Tax Arbitrage

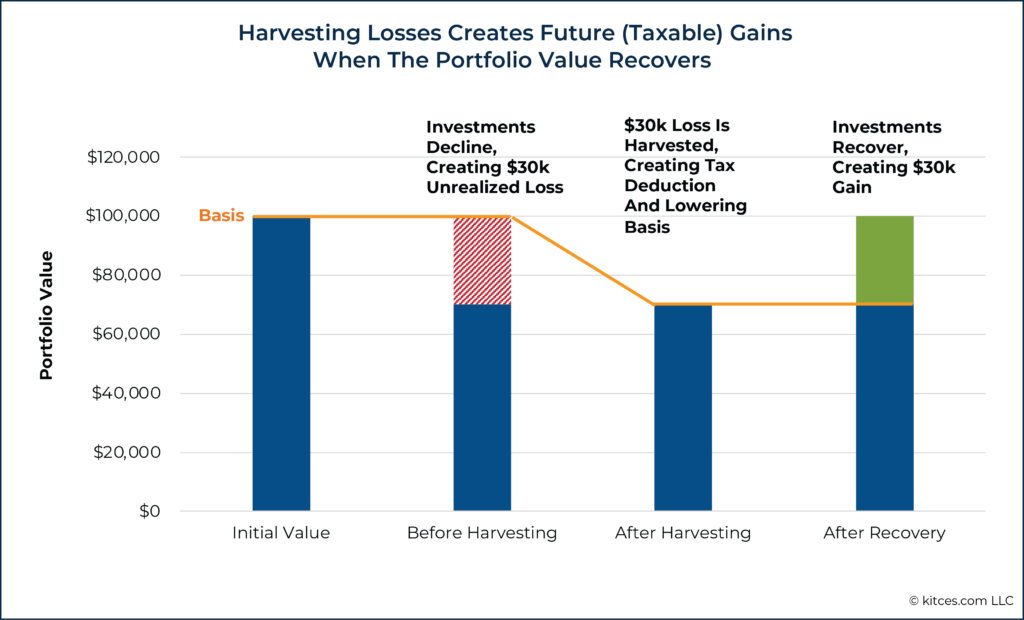

In many cases, tax-loss harvesting does not permanently reduce an investor’s taxes but rather defers them to a later date. This is because, after the investor sells the original investment at a loss and uses the proceeds to buy a similar replacement, the new investment’s cost basis is lower than that of the original. So, as seen below, if the replacement investment appreciates in value up to or beyond the cost basis of the original investment, it creates a capital gain equal to the loss that was captured by tax-loss harvesting.

Consequently, if the investor’s tax rate is the same when they harvest the loss as it is when they sell the subsequent ‘recovery’ gain, the values of the upfront tax deduction and the subsequent capital gain cancel each other out completely. The only difference is the timing of paying the tax: by harvesting the loss, the taxpayer effectively defers paying tax until they sell the recovery gain.

There is modest value in that tax deferral. By putting the tax off to a later date, the taxpayer is able to invest the funds that would have otherwise gone toward paying tax, and any growth on those funds (minus capital gains tax on the growth itself) represents a net gain for the investor. But the funds actually need to grow in order to achieve this gain, and it may take many years for that growth to compound enough to achieve substantial extra wealth. So when the investment horizon is short, or the investment has a low growth rate, the tax deferral benefits alone of tax-loss harvesting might be minimal.

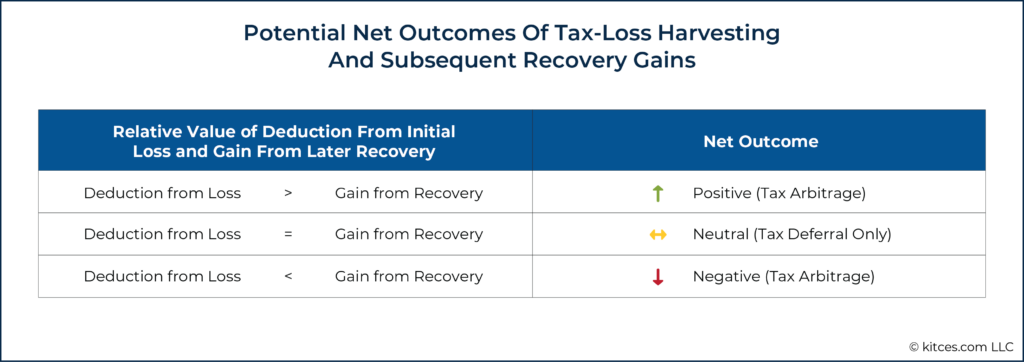

There is a greater chance of the investor gaining from the strategy if they are able to realize a deduction from a capital loss at a higher tax rate than the recovery gain of the repurchased security when it is later sold. This creates a potential opportunity for tax bracket ‘arbitrage’ and can result in an actual permanent reduction in taxes (as opposed to the mere deferral of taxes when the investors’ tax rate remains the same).

Tax bracket arbitrage can happen in several beneficial ways, including (but not limited to):

- Realizing a capital loss at ordinary income rates – either by harvesting the loss with no gains to offset it and deducting up to $3,000 against ordinary income, or by using the loss to offset short-term capital gains (which are generally taxed at ordinary income rates) – and realizing the recovery gain of the repurchased security at capital gains tax rates (which will generally be lower than the ordinary income tax rate when the loss was originally harvested).

- Realizing a capital loss at a higher capital gains tax rate, and realizing the recovery gain at a lower capital gains rate (e.g., realizing losses at 23.8%, and realizing gains at 15% or 0%).

- Realizing a capital loss and ultimately donating the repurchased security to charity (which will not pay tax on the gain when the security is sold), or never selling it and leaving it to one’s heirs, who will receive a stepped-up basis – both of which would result in never paying tax on the recovery gain.

The effect can work detrimentally in the other direction as well: If tax-loss harvesting creates a higher tax liability from the recovery gain than the initial tax savings of the capital loss, then the strategy has a net negative value over the long run.

What this all means is that, rather than having the same value for everyone, tax-loss harvesting really has a range of outcomes depending on the investor’s starting and ending tax bracket:

It may not always be possible to know which outcome will apply to a client; after all, we can’t perfectly predict things like a client’s future tax rates or whether or not they will be able to hold on to an investment until the end of their life to pass to their heirs. But advisors often use models of current and future tax rates to analyze and make informed recommendations on other questions, such as when to make Roth conversions – and doing the same can also help them decide whether tax-loss harvesting would be a good idea.

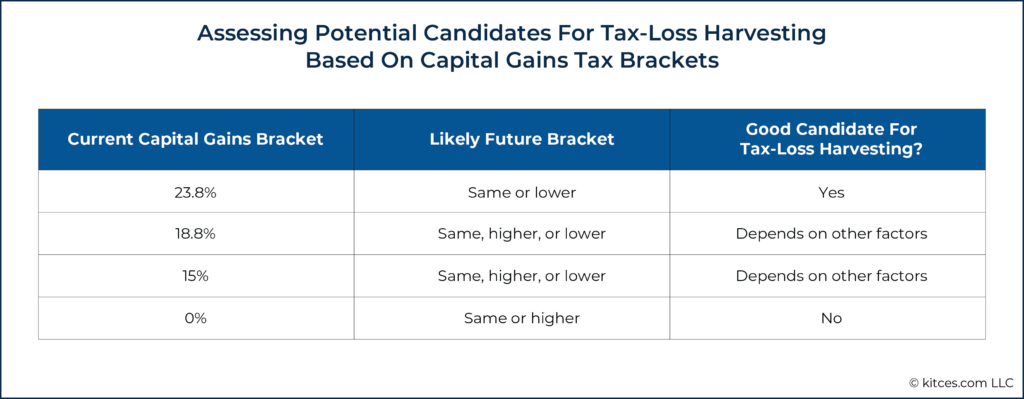

Advisors can also make reasonable predictions of the value of tax-loss harvesting for some clients based on their current tax rates. For example, a client who is currently in the 0% tax bracket for capital gains – and who, therefore, would not capture any upfront tax deduction for realizing a capital loss – would not be a good candidate for tax-loss harvesting. Because the best-case scenario for them is if they were to remain in the 0% tax bracket when they realize the recovery gain, they would end out with a zero net gain for the strategy. Alternatively, if their tax bracket changes (i.e., it goes up) in the future, realizing the recovery gain at their higher tax rate will ultimately have a negative outcome for the client.

Conversely, clients in the highest (23.8%) capital gains tax bracket are more likely to realize better outcomes from tax-loss harvesting strategies, both because of the higher initial tax savings resulting from harvested losses (and more growth on that savings over time when reinvested) and also because of the potential tax bracket arbitrage if the taxpayer were to drop into a lower tax bracket later on when their recovery gains are realized.

As a rule of thumb for deciding which clients will benefit from tax-loss harvesting, then, advisors can generally start by ruling out those in the 0% capital gains bracket (who likely stand to gain the least from tax-loss harvesting) and focusing the most on clients in the highest bracket (who are likely to benefit most). With the clients who fall in the middle, the advisor can go on to other factors that can confirm the value of tax-loss harvesting to them, such as how current and expected future tax rates compare, whether existing carryover losses might impact potential tax benefits in the future, and if the client has particular charitable and legacy plans as described above.

Step 2: Carrying Out Tax-Loss Harvesting Transactions

If the advisor determines that their client is a good candidate for tax-loss harvesting strategies and makes the decision to go ahead with harvesting losses, it’s key to do so in a way that doesn’t run afoul of the IRS’s wash sale rules, which prohibit selling an asset to capture a deductible loss and then immediately buying it (or something very similar) back to maintain their position. Specifically, IRC Section 1091 notes that if an investor sells an asset for a loss and purchases a “substantially identical” investment within 30 days before or after the day of the sale, the sale is a “wash”, and the loss is disallowed.

There are no additional penalties or taxes on wash sales per se, but if a loss is harvested with the intent of offsetting a capital gain, having that loss disallowed (and consequently having the realized gains become taxable rather than being offset by the losses) can result in a nasty surprise during tax season. And if those gains are substantial enough, they could end up bumping the taxpayer into a higher capital gains bracket, resulting in a substantial tax increase rather than savings.

Identifying Replacement Securities

The IRS is fairly specific when it comes to the certain types of securities that could trigger a wash sale: Publication 550 includes stocks, bonds, options, warrants, convertible bonds, and other types of assets under its Wash Sales section. But when it comes to pooled investment vehicles like mutual funds and ETFs, the IRS is notably vague around how to determine whether the investments are “substantially identical” and prone to the wash sales rules, which is problematic for the many advisors today who rely on these types of securities as building blocks of their portfolio management strategies.

As a result, many advisors have developed their own interpretations with the intention of finding the right balance between the advisor’s portfolio management strategy and the spirit of the IRS’s rules. These interpretations can be classified as conservative, moderate, and aggressive approaches, depending on how each security’s underlying holdings overlap with each other.

Conservative Approach: Different Fund, Different (Enough) Holdings

Because mutual funds and ETFs are generally made up of underlying holdings in stocks and bonds, some investors take the stance that two funds with a significant number of the same underlying holdings would be close enough to be “substantially identical”.

While few, if any, would argue that two funds must have completely different holdings to be acceptable as replacements, some investors have a threshold, such as no more than 70% of shared holdings between the funds (which is often enough to generate a 99%+ correlation in return outcomes); anything more would be considered identical enough to rule out as a replacement.

As a result, managers with large, diversified holdings – for instance, two active large-cap fund managers who both have several hundred stocks that ultimately have very substantial overlap – may be conservatively viewed as ‘substantially’ identical because of how closely their underlying holdings resemble one another.

Moderate Approach: Different Fund, Potentially Similar Holdings, Different Index

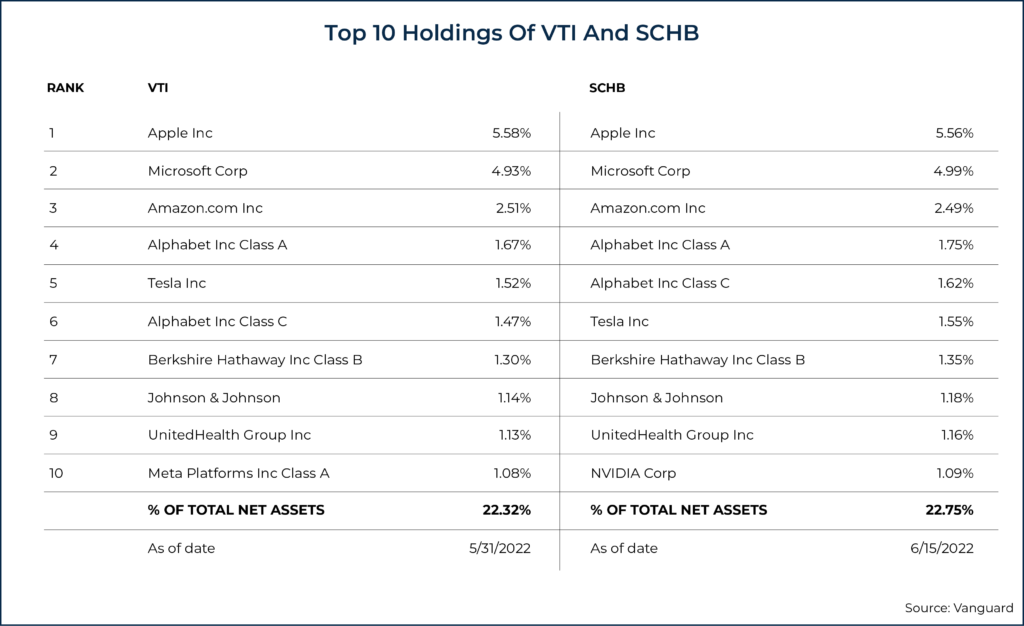

Another philosophy argues that, though two funds may have similar holdings overall, they are not substantially identical to each other if they are each tracking a different market index. So for instance, Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF (VTI) tracks the CRSP US Total Market index, and Schwab US Broad Market ETF (SCHB) tracks the Dow Jones US Broad Stock Market index.

VTI and SCHB both track market-weighted indices that are meant to represent a large percentage of the U.S. stock market, but ‘broad’ market indices tend to leave out many smaller stocks and are typically less comprehensive than ‘total’ market indices. So while both VTI and SCHB may have many of the same stocks of large corporations, VTI, a total market index fund, holds 4,100 stocks that include a wide range of large, medium, small, and micro-stocks, whereas SCHB, a broad market index fund, has only 2,486 holdings of the largest companies. Which means that these funds would be acceptable replacements for one another in this philosophy, even though their top 10 holdings are nearly identical (and their respective performance is 100% correlated):

While more conservative investors might be uncomfortable with this philosophy – especially if it was the largest (overlapping) holdings that were down and driving the bulk of the losses being harvested – it is used by many advisors who want to minimize tracking error by using highly correlated replacement funds (including robo-advisors like Betterment that automate tax-loss harvesting), meaning that if the IRS deemed these to be wash sales, it would potentially affect millions of investors who rely on those services.

Aggressive Approach: Different Fund, Same Index

Given the number of different funds that track identical market indices like the S&P 500, it’s natural to wonder if, for instance, one S&P 500 index fund like Vanguard 500 Index ETF (VOO) could be substituted for another like SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY). Though this would effectively eliminate the risk of tracking error (since it is literally both funds’ mandate to replicate the performance of the S&P 500), it could be difficult for a taxpayer, if put on the spot, to argue how the two funds are not substantially identical to each other.

However, the investor may still argue that the asset managers responsible for the funds may not be implementing them in a completely identical way, whether due to the timing of how they manage changes to the index, how they manage (albeit very limited) cash holdings and liquidity requests, or how they handle fractional shares. Though again, since they manage the same holdings in the same way to achieve the same performance, they would arguably still be substantially identical. (And notably, the wash sale requirement itself is not that they be completely identical, just substantially identical.) Which, at the least, would make this an ‘aggressive’ position to take when trying to avoid the wash sale rule.

Notably, given that there are other funds available that could achieve nearly as high a level of correlation while technically being managed to track different indices – to name one example, Vanguard Large-Cap ETF (VV) is also nearly perfectly correlated with VOO and SPY while being managed to the CRSP US Large Cap index – some advisors might find it simply not worth the risk of using two funds that track the same index.

Absent more concrete guidance from the IRS, it will come down to the advisor’s own comfort level and desire to minimize tracking errors when choosing a replacement security.

Timing And Cross-Account Considerations

The wash sale rule has a second component in addition to disallowing “substantially identical” investments. There is also a time component in which the rule is in effect, consisting of the 30-day periods before and after the day of the sale (61 days in total). The forward- and backward-looking nature of the rule makes it important to prepare to avoid wash sales that could occur anytime during the entire 61-day wash sale window, both before and after tax-loss harvesting.

A common scenario where investors are tripped up by the wash sale rules occurs when an investment pays out a dividend within 30 days of when a loss is harvested, and the investor – who has set dividends to automatically reinvest – unwittingly reinvests in the prohibited investment during the wash sale window. This can be avoided easily enough by setting up dividends so that they are not reinvested before harvesting a loss (and ensuring that none have been reinvested in the 30 days prior to realizing the loss), but there are additional ways that investors can unintentionally trigger wash sales that are more difficult to catch.

For instance, wash sales are not solely restricted to the same account in which the tax-loss harvesting occurred. In Revenue Ruling 2008-5, the IRS established that a purchase of substantially identical securities within a Traditional or Roth IRA during the 61-day wash sale window would cause a loss in the taxpayer’s taxable account to be disallowed. And even though the ruling did not specifically address other types of retirement accounts like 401(k) plans, its logic could easily be applied there as well. In other words, the purchase of substantially identical security in any of the investor’s accounts – not just their taxable account – could trigger a wash sale.

Which means that investors not only need to turn off dividend reinvestments and hold off on purchases of investments that are candidates for tax-loss harvesting in their taxable accounts, but they must also do the same for all other accounts, including retirement accounts. And in the case where an individual is investing in the same fund in their employer’s 401(k) plan, they may even need to re-allocate their plan contributions during the wash sale period so their automatic payroll deductions don’t inadvertently purchase the investment and cause a wash sale.

By the same token, the wash sale rules that apply to a taxpayer’s taxable and retirement accounts also apply to their spouse’s accounts. For married couples, then, capturing a loss in one spouse’s taxable account, then repurchasing the same security in an account belonging to the other spouse (including an IRA or 401(k) plan) is, you guessed it… a wash sale. So the same procedures necessary for the taxpayer’s own accounts – disabling automatic dividend reinvestments and contributions in taxable and retirement accounts – are also needed for the accounts of their spouse in order to avoid an inadvertent wash sale.

Avoiding Short-Term Gains When Switching Back To The Original Security

Though the main focus in tax-loss harvesting is usually on the initial trades (i.e., harvesting the loss and re-investing the proceeds into a similar-but-not-substantially-identical 'replacement' security), there remains another consideration after those trades have been executed: When to sell the replacement security and re-invest back into the original security once the 30-day wash sale period is over. In a perfect world, investors could simply sell the replacement and switch back to the original after 30 days with no additional tax consequences. But depending on what happens in the markets during the wash sale window - and depending on the investor's tax situation apart from the losses - the tax impact of switching back could negate much (or all) of the tax benefit of harvesting the loss in the first place, or even cause the investor to owe more taxes than they would have had they not harvested the loss to begin with.

If the replacement security is worth less after the end of the 30-day wash sale than its original value, it is effectively just a second tax-loss-harvesting trade: Trading back to the original security creates a loss that will be added to the investor's other losses during the year. While the value of the loss is subject to all the tax planning considerations already mentioned in this article – and the wash sale rules that applied to the first trade will also apply now when going in the other direction – there is not likely to be much downside risk in trading back to the original security.

It is when the replacement security has increased in value that there is potential danger in switching back to the original. At first glance, it would seem that selling the replacement security at a gain would simply negate part of the value of the original loss – for example, if the original loss was $20,000 and the subsequent gain on the replacement security was $10,000, one might think that realizing that gain would just reduce the value of the original loss by $10,000 ÷ $20,000 = 50%. But unfortunately, the IRS doesn't see it that way.

The main issue that occurs in this scenario is that selling the replacement security doesn't simply cancel out part of the original loss; instead, it creates an additional gain. And because the replacement has been held for less than one year, that gain is short-term in character, taxable at ordinary income rates.

Furthermore, the IRS requires that short- and long-term gains be netted against each other first before being added together to create a total gain or loss – which means that, depending on the make-up of existing short-term and long-term gains and losses, an investor may end out with a net short-term gain taxed at ordinary income rates, which would eat up a good chunk of the value of harvesting losses to begin with.

Example 2: Bennie is an investor who harvested $20,000 in long-term losses in April and reinvested the proceeds in a replacement security.

In June, after the end of the wash sale period, the replacement increased in value by $10,000. Bennie sells the replacement and invests back in the original security, realizing a $10,000 short-term capital gain.

During the rest of the year, Bennie makes several withdrawals from his portfolio and realizes an additional $20,000 in long-term capital gains.

At the end of the year, then, Bennie has the following:

- $20,000 in long-term capital losses from the original tax-loss-harvesting trade in April

- $20,000 in long-term capital gains from portfolio withdrawals throughout the year

- $10,000 in short-term capital gains from the sale of the replacement investment in June

Per the IRS's netting rules, the long-term capital gains and losses must be netted against each other first. Since the long-term loss from the tax-loss-harvesting transaction in April and the long-term gains from portfolio withdrawals both equal $20,000, they completely cancel each other out, leaving just the $10,000 short-term gain from the sale of the replacement investment in June.

If we assume that Bennie is in the 15% long-term capital gains tax bracket and the 32% ordinary income (i.e., short-term capital gains) bracket, he saved $20,000 × 15% = $3,000 in taxes by offsetting his $20,000 in long-term gains from portfolio withdrawals with $20,000 of long-term losses in the initial tax-loss harvesting trade – but he also incurred $10,000 × 32% = $3,200 in taxes by subsequently realizing the $10,000 short-term gain that resulted from selling the replacement investment in June.

Which means that in net terms, Bennie actually lost $3,200 – $3,000 = $200 from these transactions – plus he will incur more taxes when he eventually liquidates the portfolio because the basis of his investment is still $10,000 lower than before he realized the initial loss!

In general, unless the investor has realized enough short-term losses to fully offset the short-term gains, it makes more sense to wait at least one year plus one day (the point at which short-term gains and losses convert to long-term) to switch back to the original security if the replacement has appreciated in value.

The key point is that it's best to ensure that the gains and losses that might arise from switching from the replacement security back to the original will net out in a way that doesn't saddle the investor with a higher tax burden than what was saved by the original loss. Just like the decision to harvest the loss to begin with, then, deciding when to sell a replacement security is really a tax planning decision first and a portfolio management decision second, since the consequences are so dependent on the taxpayer's outside circumstances.

Ensuring That Tax-Loss Harvesting Is Carried Out Correctly

Successful tax-loss harvesting requires careful planning and execution, both to decide whether it is the correct strategy for the client in the first place and to ensure that it is carried out without running afoul of the wash sale rules. But when advisors work with dozens or even hundreds of clients (almost all of whom could be potential candidates for tax-loss harvesting, particularly in a broad market downturn), it’s almost a requirement to have some kind of framework in place to narrow down the client base to focus on those who would most likely benefit from tax-loss harvesting, and then to carry out the strategy smoothly.

Technology can provide part of the answer. There are many AdvisorTech solutions, from all-in-one investment management platforms like Orion to specialized rebalancing tools like iRebal, that provide some automation of tax-loss harvesting. But these solutions focus almost exclusively on the execution step: selecting tax lots to trade, identifying substantially identical securities that could trigger wash sales, repurchasing investments after the end of the wash sale period, and so on. These tools can make the advisor’s job easier in carrying out a tax-loss harvesting strategy, but they don’t necessarily help the advisor decide which clients would truly benefit from tax-loss harvesting. So, in reality, tax-loss harvesting software only helps with the last step in the process.

In a perfect world, there would be an all-in-one solution that could account for all of the relevant factors – current and estimated future tax rates, existing capital-loss carryovers, investing time horizon, and so on – and automate the execution of harvesting losses. But no such solution exists (that I’m aware of), and, given the client-specific nuances involved, it may not even be possible to develop a single technology that can create and execute optimal tax-loss harvesting strategies for every client all of the time. Furthermore, many advisors might be reluctant to hand over complete control to an automated tax-loss harvesting solution anyway, given the downsides (and potential liabilities) of a software glitch or user error triggering trades at the wrong times.

In reality, most advisors can use a combination of tools to go through the steps of tax-loss harvesting for their clients. Luckily, many of these tools are already integrated into many advisors’ tech stacks. For example, CRM platforms often include a field for the client’s current marginal tax rate, which the advisor can use to pull a report to filter out clients in the 0% capital gains bracket who would not be likely to benefit from tax-loss harvesting.

For the remaining clients, financial planning software like RightCapital can model the client’s future tax rates to provide a better idea of the tax liability their recovery gain might produce. Combining these tools with the advisor’s own knowledge of the client’s goals and plans allows for a repeatable framework, such as the one below, that can systematize the process of tax-loss harvesting for a large number of clients:

Step 1: Pull CRM reports of clients by their marginal tax rates, and filter out those in the 0% capital gains bracket (the least likely group to benefit from tax-loss harvesting).

Step 2: For those in the highest (i.e., 23.8%) capital gains bracket, review for any red flags (such as plans to sell investments within one year or carried-over losses that won’t be used in the client’s lifetime) that could jeopardize the value of harvesting losses.

Step 3: For clients in the ‘middle’ (i.e., 15% and 18.8%) capital gains brackets, review the clients’ plans for future withdrawals and analyze their future tax rates in the financial planning software. Rule out clients for whom the future tax liability from harvesting losses would be higher than the initial tax savings.

Step 4: For the remaining eligible clients, review for previous trades that may trigger wash sales rules and use investment management/rebalancing software to execute tax-loss harvesting.

The above steps can be repeated at regular intervals (e.g., quarterly or monthly) and integrated into the advisor’s portfolio rebalancing process. While some advisors may go about it in slightly different ways (depending, for example, on the amount of back-office support they have available to perform the analysis of current and future tax brackets), the steps above should be manageable for most small- and medium-sized firms to add value with tax-loss harvesting for their clients without bogging down their resources.

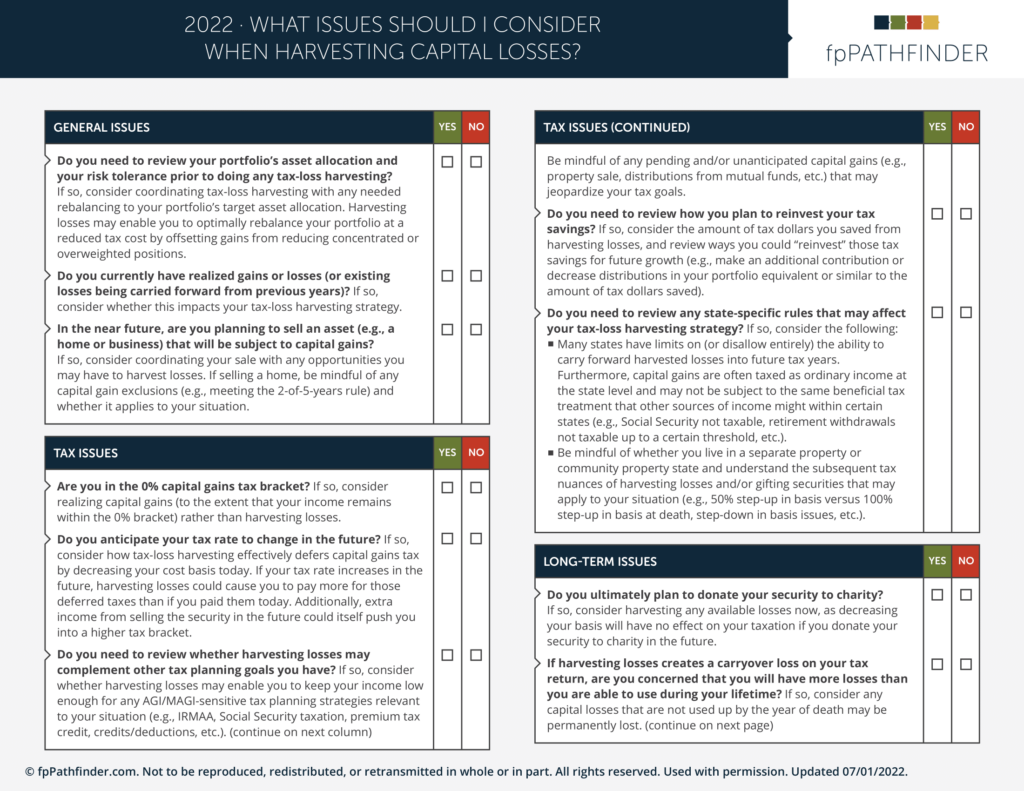

A Checklist For Tax-Loss Harvesting

It’s important for advisors to be proactive in determining not only when it is a good time to tax-loss harvest, but also how to go about it to ensure the value of the loss is captured as intended. With so many moving parts to consider, a checklist such as the one below can help to ensure that no important steps or information get missed:

With the speed at which markets move, it can be tempting to act quickly to capture losses when the market is down and provide at least a nominal ‘win’ during difficult times. However, the reality is that tax-loss harvesting is just one way – and a relatively narrow one at that – that advisors can help clients during down markets. When done quickly and without regard for the client’s bigger picture – from their retirement accounts to their retirement income plans – tax-loss harvesting can just as easily have a negative outcome for the investor as a positive one.

By slowing down to carefully consider the client’s current and future tax rates and other circumstances that might be relevant, advisors can overcome the temptation to make haste by simply doing something and, instead, be certain that what they eventually end up doing is well thought out and valuable for the client in the long run.

Ben, great piece!

Have there been any indications that the IRS views TLH by swapping two ETFs benchmarked to the same index unfavorably?

Hi Zach, thanks for reading! To my knowledge, there haven’t been any publicly-released rulings or guidance from the IRS on what might make one ETF “substantially identical” to another. However, it’s worth noting that two ETFs benchmarked to the same index would likely have a near-100% overlap in underlying holdings. That might not tell the whole story – e.g., if one ETF was passively managed to the index while the other was actively managed, the IRS could be less likely to see them as substantially identical – but on the holdings alone it would be tough to argue there is a substantial difference if the IRS did push back.

The IRS’s rules on options straddles do give a specific threshold of underlying securities – 70% – that makes up the line substantially identical and not, so some advisors use that as a guideline even though it wasn’t specifically written for ETFs

Of course, many advisors (including robo-advisors) also take the more aggressive approach of swapping out ETFs that track the same index, so there seem to be many people willing to bet that the IRS won’t notice, or won’t push back on, that strategy. So far they don’t seem to have been wrong, but time will tell if the IRS decides to start taking a harder look at tax-loss harvesting trades.

Note that the straddle rule language is “substantially similar,” not “substantially identical.” The former would tend to be seen as a lower barrier. It is very conservative to stay under 70% overlap based on the straddle standard.

Regarding replacement securities, would holding the sale proceeds in cash and then repurchasing the sold security after 30 days not be the better practice? You really have only one potential negative outcome, the sold security goes up in value and you repurchase at a higher price a security that is a long term holding anyway. Buying a replacement security, you could both be selling the replacement security for a ST Gain and buying back the sold security at a higher price.

Possibly, but the question then is: if the value of the replacement security went up significantly – say by 5% – during the 30-day wash sale period, would you rather (1) be up by 5%, but need to do some planning to minimize the tax consequences of getting back into the original; or (2) not have participated in the 5% gain at all, but be able to easily re-purchase the original security?

There’s not necessarily a single right answer to this, but it speaks to the importance of figuring out a game plan in advance for getting back into the original security. Maybe in some lower-volatility asset classes, like bond funds, parking the proceeds of the tax-loss harvesting trade in cash for 30 days might make more sense because there’s less chance of a big short-term gain. Maybe if there’s a high chance for tracking error between the replacement and the original, you’ll want to swap back out as soon as the short-term gains become long-term. What’s important is to know what you’re going to do BEFORE doing the initial tax-loss harvesting trade, so you aren’t at a (figurative) loss when you have a (literal) gain to deal with.

Great piece Ben. Few questions:

1) If clients are at least in 22% or higher marginal today, would you agree TLH should typically at least break even since client can deduct $3k from ordinary income today, and at worse realize 20% cap gains rate later?

2) You mention a risk to TLH is how long taxes can be deferred along with compounded growth associated with tax-deferred growth. Can you re-explain what this means, and if you rebuy a nearly identical security is this risk still valid?

thanks!

Hi Jay – I apologize I’m just seeing this. Good questions!

1. The first caveat is that most people in the 20% capital gains tax bracket actually pay 23.8% on most or all of their capital gains because of the Net Investment Income (NIIT) tax on investment income above $200,000 (S) / $250,000 (MFJ). So if there is a bracket for harvesting losses at ordinary rates that’s likely to at least break even (assuming capital gains rates don’t change in the future), it’s the 24% bracket.

2. Let’s say you’re in the 15% capital gains tax bracket and you harvest a $10,000 loss that offsets a $10,000 gain. Your upfront tax savings from harvesting the loss is $10,000 x 15% = $1,500.

Now, you re-invest that $1,500, and it grows at a 6% annual rate for the next 10 years, you’ll have ($1,500 x (1.06^10) = $3,594.84. If at that point you liquidate the investment – again in the 15% capital gains bracket – you’ll owe back the original $1,500 (because the basis in your investment is $10,000 lower from harvesting the loss), but you’ll have $3,594-$1,500 = $2,094 more than you would have had without harvesting the loss (though you’ll also owe capital gains on the $2,094 itself, you’ll still come out ahead). That’s the tax deferral value of tax-loss harvesting.

The longer the time horizon you have to invest, the greater the deferral value, because there is more time for that re-invested tax savings to compound. Conversely, if you liquidate after only a year or two, the deferral value is much less. And if you don’t invest the upfront savings at all, then you completely miss out on the deferral value and end up just breaking even.

So even if you buy a nearly-identical replacement security in place of the original, you need to invest the upfront savings to realize the tax-deferral benefits. And the longer you wait until liquidating the investment, the more value there is in that deferral.