Executive Summary

Judge Learned Hand once famously stated that “Any one may so arrange his affairs that his taxes shall be as low as possible” and that there’s no duty to pay any more in taxes than is absolutely necessary. And the corollary when it comes to an investment portfolio might be “Any one may so manage a portfolio to defer taxes as long as possible,” given that if the investor ever intends to use the money, eventually the tax bill must still come due, but it still pays to minimize tax drag along the way.

Yet while it’s appealing to manage investments in a tax-efficient manner – or buy “tax-managed” mutual funds to do it for you – in today’s tax environment, there actually is such thing as being too tax efficient and deferring too much in taxes for too long.

The reason is that since the beginning of 2013, investors effectively face four different capital gains tax brackets (including the 3.8% Medicare surtax on net investment income), with higher rates applying to higher levels of income and larger capital gains. Which introduces the possibility that an investor is so tax efficient, and defers their tax liability for so long, that when the taxable event finally occurs, the sheer size of the gains propel the investor into higher tax brackets, who then ends out finishing with less wealth!

Which means ultimately, while “tax drag” is bad, and strategies to minimize it – such as tax loss harvesting – are valuable, doing too much tax minimization now can just cause even more harm later. Instead, for some investors, the best approach is to recognize that in low tax rate years it’s better to harvest the gains instead of the losses. And in other situations, the best way to minimize tax drag is not to buy a tax-managed mutual fund at all, and instead leverage the asset location opportunity of sheltering growth investments that generate capital gains inside of an IRA (or ideally a Roth IRA) instead.

The Anti-Compounding Effect Of Tax Drag

A fundamental challenge of accumulating wealth is the burden of government taxation. In the U.S., as with most countries around the world, we tax income as it is generated every year, whether from the fruits of our labor or the growth or yield of our capital. And to the extent that Uncle Sam taxes the income, there’s less we get to keep for ourselves, whether to spend or save.

In the context of investors and their portfolios, the impact of taxation means that when a portfolio generates a return, only a portion of that return is available for the investor to keep and reinvest for the future. Which means there’s less money to enjoy the benefits of future returns. Over time, the lost compounding produces a “tax drag” on the cumulative growth of the portfolio.

In the short term, the direct impact of taxation may be immediate (not all the returns stay in your pocket), but the consequences of tax drag are minimal, because there haven’t been a sufficient number of years for those lost tax dollars to have grown in the first place. (And either way, the tax bill was going to come due eventually.)

Example 1. Jeremy’s $100,000 investment grew by 8% last year (an $8,000 return), but that growth was subject to 25% taxation, reducing the available dollars for reinvestment to only $6,000. However, that $2,000 tax bill was going to be owed someday no matter what; to Jeremy, the true lost economic value was the growth that could have occurred on that $2,000 tax bill. At an 8% future return, the $2,000 could have grown by another $160, which relative to Jeremy’s $100,000 account balance is “just” 0.16% of foregone returns. While that dollar amount is not irrelevant, it is a very small financial impact.

In the long term, though, the impact of tax drag becomes more pronounced. Every year of taxation is another year where a portion of the gains are lost to taxation instead of being able to reinvest, which cumulatively adds up to a significant amount of foregone growth over time. In addition, the longer the time horizon of the portfolio, the more years those tax dollars (particularly the early payments) lose out on multi-year compounding growth.

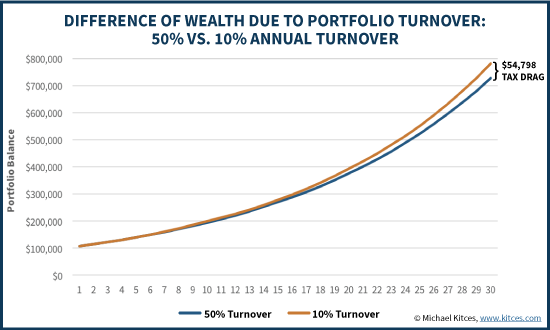

Given enough time, tax drag alone can produce a substantial difference in cumulative wealth. For instance, the chart below shows the long-term wealth impact of an equity portfolio that generates 8% annual growth and is subject to a 15% capital gains tax rate, when facing either 10% vs 50% annual turnover.

As the results show, the higher turnover rate produces a trivial difference in wealth initially, but a very material compounded difference due to tax drag over time. Over a multi-decade time period, tax drag alone equated to a 0.24% difference in the (after-tax) average annual compound return, even after accounting for taxes that would be due at the end!

Indexing Or Tax-Managed Mutual Funds To Reduce Tax Drag

The potential impact of tax drag on long-term compounding returns is serious – a similar order of magnitude to the impact of investment expenses. Consequently, as with the impact of investment costs, it’s even possible to have an investment strategy that generates investment outperformance on a gross return basis, but produces lower returns on a net (after-tax) basis, once the impact of tax drag is considered. In fact, Morningstar even calculates a “tax cost ratio” to measure how much of a fund’s annualized return is being lost to taxation (which, again, in some cases may more-than-offset any outperformance from the fund’s investment strategies on an after-tax basis).

Accordingly, this recognition that tax drag might completely offset at least modest investment outperformance (in a world where it’s already difficult to find alpha) has led to a growing number of “tax-aware” investment approaches. Most commonly, these include indexing and tax-managed investing (also sometimes labeled as “tax-efficient” investing).

The indexing approach to managing tax drag is simply to make the decision that if tax drag is bad, and is caused by turnover, the easiest solution is simply to invest to a (static) allocation of index funds that will have no (material) turnover. If no trades occur, no taxable events occur, and there can be no tax drag. (Notably, at least some small amount of trading must occur, simply to rebalance and prevent portfolio drift, although otherwise-passive pure rebalancing activity generally triggers no more than a roughly 2% turnover rate over time.)

Alternatively, the “tax-managed” approach is one that ultimately still accepts that turnover may trigger taxation (and that active management strategies may necessitate some turnover), but explicitly looks to minimize taxable turnover (or more generally, any taxable events). This might be accomplished through a combination of several tax strategies, from using specific lot identification to choose the highest cost basis shares to be sold when a partial sale occurs, to doing tax loss harvesting to offset any recognized (or anticipated) capital gains, or in the extreme deciding not to do a particular sale that might otherwise have been appealing but isn’t executed because it’s just “not worth it” given the looming capital gain that would be triggered.

Given this demand, the “tax-managed investing” category of funds has grown significantly in the past decade.

The Downside Of Tax-Efficient Investment Strategies

While the compounding impact of tax drag is a real ‘cost’ in the long run, and therefore valuable to manage to the extent possible, there is a significant caveat to trying to minimize (or entirely eliminate) turnover for an extended period of years.

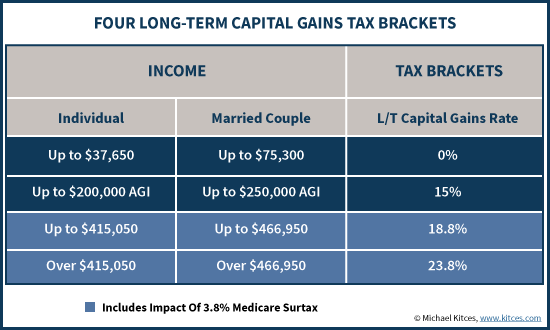

The issue that arises is the existence of multiple capital gains tax brackets, that have progressively higher rates at higher income levels. Under current law, those in the bottom two ordinary income tax brackets (10% and 15%) are eligible for 0% long-term capital gains rates, while anyone subject to the middle four tax brackets (25%, 28%, 33%, and 35%) pay a 15% long-term capital gains rate, and those in the top 39.6% tax bracket are subject to a 20% capital gains tax rates. In addition, individuals with an AGI above $200,000 (and married couples over $250,000) also face a 3.8% Medicare surtax on net investment income, which includes interest, dividends, rents, royalties, annuity gains, passive income, and virtually any otherwise-taxable capital gain. Thus, taxpayers are effectively subject to four capital gains tax brackets: 0%, 15%, 18.8%, and 23.8% (plus state income taxes as well where applicable).

The reason this capital gains tax structure is problematic is that the higher capital gains tax rates themselves are triggered by larger capital gains. Which means that “extremely tax efficient” investment strategies that minimize current capital gains taxes can create even larger tax bills later!

Example. Fred and Ethel are married and generate about $90,000 of ordinary income after deductions, from a combination of Fred’s pension, the couple’s joint (and mostly taxable) Social Security benefits, and taxable interest income from their portfolio. Their investments are also generating an average of about $50,000/year of long-term capital gains. If the couple recognizes the gain every year and pays taxes on it, their long-term capital gains tax rate will be 15% (as the couple is in the 25% ordinary income bracket), resulting in $75,000 of cumulative taxes over the next decade (on $500,000 of cumulative gains).

If Fred and Ethel instead decide to deploy a tax-managed investing strategy that minimizes their capital gains (by not trading them at all, and/or finding an investment to loss harvest to offset any gains), then by the decade Fred and Ethel will have a $500,000 unrealized gain. However, if the couple ultimately needs to make an investment change after that cumulative gain, and triggers the (large) long-term capital gain then, the gain will be taxed at a blend of 15, 18.8%, and 23.8% rates.

The end result: the couple ends out paying significantly more in taxes by being tax efficient for a decade! Of course, the virtue of the more tax efficient approach is that at least if there’s a higher tax bill, it’s not paid until later. However, the investor would have had to earn a significant internal rate of return for the first decade to actually come out ahead, given the tax liability that occurred at the end!

And notably, this dynamic is playing out today. For instance, many tax-managed mutual funds today have very large embedded capital gains, thanks to the 7-year bull market. That’s been great for tax efficiency along the way, but it now turns into a tax time bomb where the investor/manager will find it harder and harder to make investment changes as “everything” has a big embedded capital gain. And triggering “too much” in gains at once can propel the investor into higher tax brackets and actually result in less wealth in the end!

Or viewed another way, there really is such thing as being “too good” at deferral capital gains (at least, for those who ultimately intend to use the money and won’t be donating it to charity or a donor-advised fund, or holding it until death for a step-up in basis).

How To Manage The Tax Efficiency Tax Bomb

So how can advisors help investors manage the potential tax bomb of being “too” tax efficient in a portfolio?

The solution is not merely to ignore trying to be tax efficient. While not being tax efficient may avoid amplifying tax exposure in the future, blindly increasing turnover may just accelerate taxes today for no reason. After all, deferring “too much” in gains to the future can trigger higher tax brackets, but deferring some gains into the future is still good tax deferral, taking advantage of the time value of money.

Harvesting Capital Gains

The first strategy for managing to good tax efficiency (but not “too good”!) is to monitor for years where it may be effective to harvest capital gains. Harvesting capital gains – similar to harvesting capital losses – is a transaction where the clients sells an investment and buys it back again. Except while harvesting losses involves selling an investment with a loss (claiming the tax loss and stepping down the cost basis, but waiting the 30-day wash sale period), harvesting gains is about selling an investment that is up and buying it back again (which, notably, can be done instantaneously as the wash sale rules only apply to losses), which triggers a tax gain but steps up the cost basis in the process.

Of course, aggressively harvesting capital gains is simply the equivalent of ‘causing’ high portfolio turnover, and can trigger higher capital gains tax rates today (which isn’t productive). Instead, the goal is to harvest only to the extent that the taxes paid today can avoid being subject to even higher capital gains rates in the future, such as systematically harvesting at 15% rates now to avoid a cumulative gain that would be taxed at 18.8% or 23.8% in the future.

And if the investor’s long-term capital gains rate is 0%, it is virtually always appealing to harvest the gains, as it’s hard to get a rate better than 0% in the future (though watch out for the indirect effects of 0% capital gains, including triggering the taxation of Social Security benefits and the impact of state income taxes).

Notably, investors should be wary of tactics that harvest capital gains for mutual funds, though, as harvesting gains of the fund itself still leaves the investor exposed to potential (additional) end-of-year capital gains distributions from the fund based on its own internal activity. Even with tax-managed mutual funds, which generally distribute less in gains (as that’s the whole point), there’s still a risk that with years of cumulative gains, the fund may eventually have little choice but to distribute at least some (potentially significant) capital gains, representing years’ worth of prior tax deferral being liquidated all at once.

Asset Location As A Tax-Efficiency Alternative

An alternative strategy to manage the potential capital gains exposure of a portfolio is to not seek out “tax-managed” investments in the first place, but to simply own investments that generate turnover inside of tax-deferred retirement accounts instead. In essence, this simply means relying on the tax-preferenced retirement account “wrapper” as the tax efficiency tool, rather than the other tactics for minimizing tax drag.

In fact, tax-deferred retirement accounts like an IRA can be so effective at reducing tax drag that holding stocks in an IRA can actually result in more wealth than holding them in a brokerage account in the long run, despite the fact that preferential capital gains rates will be converted into ordinary income. In other words, the tax drag of even just a moderate level of dividends and portfolio turnover (e.g., 2.5% dividend rates and 20% turnover) does even more harm than losing out on capital gains tax rates over very long (i.e., multi-decade) time periods. And of course, the tax-free Roth IRA avoids tax drag altogether simply by virtue of being a tax-free account.

The bottom line, though, is that while tax drag can significantly (and adversely) impact wealth accumulation, avoiding it through various “tax-efficient” investment strategies (including tax-managed mutual funds) isn’t necessarily better if it creates cumulative capital gains so large that it triggers higher tax rates. Notably, that doesn’t always mean a year with very large capital gains is a “tax disaster” (at least as long as the tax rate isn’t propelled higher); it can merely be a sign of years’ worth of prior tax efficiency! But ultimately, there is such thing as being too tax efficient with a portfolio, such that years of low tax bills eventually lead to especially large tax liabilities – at higher tax rates – when those investments eventually need to be sold, whether to make investment changes or simply to consume in retirement!

So what do you think? Have you had challenges where the portfolio was so tax efficient that eventually huge capital gains became inevitable? Do you ever have clients who are upset with their big capital gains who don't recognize it's a result of years of prior tax efficiency along the way?