Executive Summary

In the world of investing, the Holy Grail is finding an investment manager who can reliably, persistently deliver alpha – a feat that seems to be of increasing rarity, as active managers in the aggregate continue to see outflows due to ongoing underperformance.

Yet in their new book “The Incredible Shrinking Alpha”, Larry Swedroe and Andrew Berkin make the case that the woes of the active management industry are not merely an artifact of the post-financial-crisis investment environment, but are a result of the ongoing evolution of the investment management industry.

As research continues to identify unique risk factors that are rewarded with excess returns, what was once believed to be alpha is increasingly turning out to be an active manager who simply invested to benefit from a not-yet-identified-as-such risk factor. Yet as the number of known risk factors increases – along with the availability of new solutions to passively invest in them at a low cost – it is more and more difficult to find active managers really adding something beyond an appropriately-factor-adjusted benchmark. And the situation is only further complicated by an increasing volume of professional managers competing against each other for a limited pool of available alpha where it is harder than ever to outperform against similarly-highly-skilled peers.

Of course, the caveat is that just as the investment research has evolved from one factor to three and now five, more factors may be found in the future that still create alpha opportunities in today’s marketplace. And given that not all factors are favored at once, tactically allocating amongst the risk factors may also present an opportunity for an active manager to add value. Nonetheless, Swedroe and Berkin do make a compelling case that the odds an active manager can even find any alpha, and wrest it from increasingly competitive set of peers, is not great, as getting a hold of a reasonable share of the shrinking pool of alpha is truly harder than it has ever been.

In his now-famous 1991 paper, “The Arithmetic of Active Management”, Bill Sharpe noted that active management in the aggregate is a zero-sum game. After all, the market itself is comprised of the aggregate of all the underlying transactions in the first place… which means by definition, the weighted average returns of active investors must add up to the market itself. Some investors will outperform (by luck or even by skill), but an offsetting number must underperform (again by luck or [lack of] skill) as well. And to the extent that transaction and management costs drag the return down, the after-expenses sum of active management is negative.

Notwithstanding this truth in the aggregate, though, there are no shortage of active investors who try to be in the “outperforming” group, seeking to either be (or find) a manager who can deliver “alpha” – an excess return after accounting for exposure to risk. And while such managers are rare, they can be found historically – from Graham and Dodd and John Maynard Keynes to Peter Lynch and Warren Buffett. Yet a growing base of research is raising the question of whether even the greatest investment managers in history were really active investing geniuses, or were simply rewarded for investing in and taking advantage of a unique form of risk factor that just hadn’t been identified as such at the time.

When Alpha Is Just Beta In Disguise

In their new book “The Incredible Shrinking Alpha”, authors Larry Swedroe and Andrew Berkin make a compelling case for how our ever-improving understanding of markets and their risks (and associated rewards) are undermining the very existence of alpha.

In their new book “The Incredible Shrinking Alpha”, authors Larry Swedroe and Andrew Berkin make a compelling case for how our ever-improving understanding of markets and their risks (and associated rewards) are undermining the very existence of alpha.

The key distinction is to recognize that alpha is measured as an excess risk-adjusted return – the outperformance of the investor over what could have been achieved simply by (passively) owning the underlying (market) risk of beta. In its original formulation under the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), the “beta” was simply the risk of the overall stock market. Alpha was the excess return of the investor above what would have been expected due to market risk alone.

However, subsequent research found that there were certain persistent factors that resulted in excess returns – risk factors that provided their own unique reward beyond just the reward for taking market risk. In the 1980s, a series of studies came forth showing that excess returns had favorable relationships with stocks that were either small cap, high-earnings-yield, and/or low-book-to-market. These “size” and “value” risk premia were highlighted in the now-famous 1992 paper “The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns” by Fama and French, who found that their three-factor model (size and value, in addition to market exposure) could explain more about investor returns than “just” CAPM and market risk alone.

In the process of adopting the three-factor model, though, Fama and French’s research indirectly explained the investment outperformance of many historically famous and successful investors. For instance, the success of Graham and Dodd (and many of their value-investing predecessors) can be explained heavily by the fact that their portfolios – by definition of their value school approach – were tilted heavily towards value, which Fama and French had shown is a unique risk/reward factor. In other words, once controlling for a comparable amount of value exposure in a passive portfolio, much of the outperformance for many value investors seems to disappear. Similarly, a small-cap investor who appears to generate excess long-term returns may in reality be doing nothing more than taking advantage of the passive small cap premium that is available; again, once compared to an appropriate small-cap-weighted benchmark, the outperformance of many (small cap) investors disappears altogether.

In essence, the key is that many successful active investors aren’t actually successful because of their investing efforts, per se, but simply because their process is providing them exposure to risk factors that would reward any investor, even a passive one. In other words, what looked like alpha and excess risk-adjusted return against the “wrong” (or at least, incomplete) benchmark, merely looks like matching market performance (or worse) once the benchmark is adjusted for the appropriate (small and value) risk factors!

Similarly, Mark Carhart’s 1997 study “On Persistence in Mutual Fund Performance” found a fourth factor of momentum (measured as the average return of the top 30% of [positive] momentum stocks minus the average return of the bottom 30% of [negative] momentum stocks), which in turn reveals that some outperforming managers were taking advantage of a momentum effect that, again, could have been replicated and invested passively.

And even more recent research is finding the potential presence of a fifth factor of profitability; Swedroe and Berkin cite a study “The Other Side Of Value: The Gross Profitability Premium” by Robert Novy-Marx finding that high-quality persistently profitable firms seem to generate significantly higher returns despite typically having higher valuation ratios than the least profitable (and lower-valued) stocks. In fact, a just-released study from Fama and French is now articulating a “Five-Factor Asset Pricing Model” of market, size, value, profitability, and investment (the latter representing the company’s investment into new assets), although notably the profitability and investment factors appear to subsume the value factor.

The significance of all these risk factors and their associated rewards is that they go a long way towards explaining the incredible returns of even Warren Buffett – who built an amazing track record with a career of buying stocks that were safe, cheap, and high-quality, but may have simply been capturing some of the available return premia from the value and quality (profitability and investment) factors. In other words, yes the returns of the companies that Buffett buys have been amazing, but so were the returns of almost any stocks with similar value and profitability/quality characteristics!

Notably, the key point here is not to undermine the great results of investors with long-standing track records of success like Buffett or Graham and Dodd – these factors may go a long way towards explaining their results in retrospect, but the factors were not recognized as such, and couldn’t be invested as such, at the time.

Going forward, however, when an increasing number of passive investment vehicles/managers are available that can provide access to these factors at a low cost, it’s no longer worthwhile to pay an investment manager who merely replicates the same results at a higher cost. In other words, favorable results that were once characterized as active manager alpha are, in the future, nothing more than factor-loading beta – and in the process, Swedroe and Berkin emphasize that the pool of available alpha has been dramatically reduced, and is continuing to shrink as more factors are added!

A Review Of The Increasingly Competitive Landscape For A Shrinking Pool Of Alpha

In addition to the phenomenon that the pool of available alpha is shrinking as research reveals more and more factors that allow even a passive investor to take advantage (without the active management cost), Swedroe and Berkin also note how the dynamics are changing amongst the players for that pool of alpha as well.

The first notable shift is that individual households – classically known as the “dumb” money against which the “smart money” institutions would trade to generate the biggest alpha – are forming a smaller and smaller share of direct equity ownership in the first place. At the end of World War II, households held more than 90% of U.S. corporate equity; by 1980, the ratio had fallen below 50%; and by 2008, it was down around 20% (and the trend certainly isn’t materially reversing since the financial crisis).

To some extent, this shift is because consumers have increasingly relied upon mutual funds and professional managers – instead of being direct equity investors – yet the explosion of mutual funds, paired with the decline of direct individual investors, means that professional fund managers are now mostly just competing against each other! As Swedroe and Berkin note, there are now over 7,500 mutual funds, up 14-fold since 1979, and paired with the explosion of hedge funds as well (up from $1T to $3T in assets in just the past decade), it is estimated that as much as 90% of daily trading is simply institutional investors (trading mostly with and against each other!). In other words, if individual investors are the “low-hanging fruit” for the smart money to generate alpha by trading against, there isn’t much low-hanging fruit left to take advantage of (with at best 10% of daily trading being done by non-institutional investors), which further shrinks the pool of potential alpha.

The fact that the overwhelming majority of trading is now amongst professional investors trading with each other has another indirect effect as well – it becomes more and more difficult to become a standout manager, because outperformance comes not from absolute skill but from the relative superiority of skill over the other participants. In other words, even the most amazing investor in history will have trouble outperforming when his/her competition are other investors who are also better than anyone else in history; the overall skill level may be drastically higher, but the expected outperformance is actually lower, as the range of outcomes narrow.

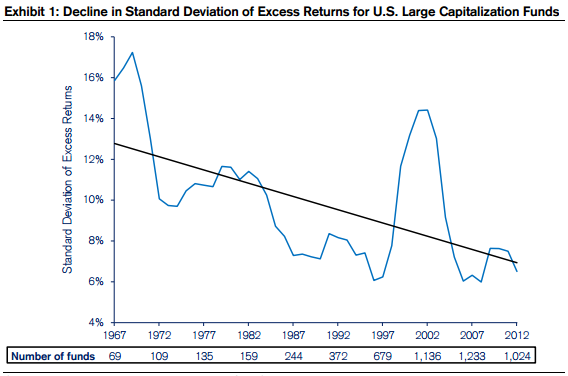

Dubbed “The Paradox Of Skill”, this phenomenon is the same that helps to explain why there has been no baseball player to hit over .400 since Ted Williams in 1941; while the average baseball hitter is far better today than in 1941-and-prior, implying there should be even more .400 hitters, the reality is that there are also far better fielders and pitchers, and the end result is that as the average skill of all baseball players has increased, the range of results has actually narrowed while the average remains the same. Thus, in 1921 the average hitter batted a little over .250, with a standard deviation of 40.6 points; by the early 2000s, the average hitter still batted a little over .250, but the standard deviation was down to 26.1, as the rising average skill level reduced the ability for any one player to stand out. Hitting over .400 has gone from being a 3-standard-deviation event to a 5-standard-deviation event, even as the quality of hitters improved!

And researchers are finding that this “Paradox of Skill” effect is present in the search for alpha as well, as the standard deviation of excess returns is shrinking as well and it’s becoming harder for anyone to be a standout performer; by one study, about 10% of managers showed statistically significant skill in outperforming in the late 1980s, but it’s down to 1.6% today.

Beyond even all these challenges, Swedroe and Berkin also note the caveat that by some research, alpha itself may literally be a finite resource; there’s just only so many “investment mistakes” on the table, in the aggregate, for professional managers to monetize and carve up amongst themselves. Which means as the active management industry has grown larger in recent decades, it’s spreading the available alpha thinner and thinner.

For instance, Swedroe and Berkin note that hedge funds researcher David Hsieh once estimated the total amount of alpha on the table for hedge funds is about $30B per year; when the industry was $1T in total, this meant there was potential for 3% of (gross) alpha per hedge fund. When the industry was even smaller the prior decade, with only $300B under management, each fund had the potential for 10% alpha. Yet in today’s environment, with a $3T+ hedge fund industry, that pool of alpha may be down to only 1%/year. Which is not terribly promising for investors in a world where hedge fund fees are often 2% of investments, plus 20% of alpha (if there’s even any left!?).

Be Passive, But Not Necessarily An Index Fund Investor– An Indirect Plea For Smart Beta?

Given these dynamics – that the pool of alpha was/is of limited size to begin with, is shrinking as much of what was once believed to be alpha is now beta, is shrinking further as the most mistake-prone individual investors stop participating directly, and whatever is left must be finitely divided amongst a larger number of players, who in turn are increasingly professionals with higher average skill where it is difficult to stand out – Swedroe and Berkin perhaps not surprisingly reiterate Charles Ellis’ reprise that active management is “The Loser’s Game”. In other words, investors would be better off simply trying to invest passively at the lowest feasible cost to capture as much as the factor-based beta as they are comfortable (given risk tolerance), and forego trying to win the “loser’s game” of finding a “good” active manager and paying the costs of active management.

Notably, though, Swedroe and Berkin do not necessarily equate “passive” investing with “index” investing. As they note, traditional index investing does not necessarily take advantage of most of the available factors like small, value, momentum, and quality; the only factor explicitly included is the “original” beta of market exposure. Accordingly, the alternative is to construct passive portfolios, not based on indices but designed specifically to maximize (or at least optimize based on risk tolerance) the exposure to those factors.

Swedroe and Berkin also note other negatives to pure/classic indexing, including: because (most) indices are reconstituted annually, even if they have exposure to certain (desired) risk factors, it won’t necessarily remain constant over time; the process of reconstituting the index can result in higher trading/transaction costs, in addition to the danger of being front-run by other managers; inclusion of “all” stocks in the index may not only fail to overweight “favorable” factors, but will fail to underweight known-to-be-unfavorable factors (i.e., there is research showing “penny” stocks, extreme small growth stocks, stocks in bankruptcy, and IPOs, all have poor risk-adjusted returns, but those stocks are still included in an all-encompassing index fund); and limited control of certain tax features (e.g., some tax-loss harvesting strategies, meeting the holding period requirement for qualified dividend treatment, losing qualified dividend treatment due to securities lending activity, etc.).

In fact, although they don’t ever directly use the label, Swedroe and Berkin appear to be supporting so-called “smart beta” strategies, where portfolios are not necessarily actively managed on an ongoing basis, but are not simply invested to cap-weighted index funds, either. In fact, there are arguably many parallels between Rob Arnott’s “Fundamental Indexing” smart beta strategies, and the kinds of portfolios that would be designed under Swedroe and Berkin’s factor-based approach (they simply use slightly different factors).

To say the least, the authors do seem to indirectly make the point that there is a mid-point between “ongoing active management” and “passive indexing” (which perhaps needs a better name than “smart beta” to describe?) that investors should be considering, where the role of the manager is relevant for upfront portfolio design, even if the portfolio is not actively managed/adjusted thereafter.

Finding The Next Alpha Factor, And Dynamic Factor Rotation?

Notwithstanding Swedroe and Berkin’s admonition against the pursuit of (an ever-shrinking) alpha, for those who do wish to continue trying to pursue it anyway, “The Incredible Shrinking Alpha” also provides some indirect but key takeaways in how to go about it.

First and foremost, there’s the fact that the research started out as one factor, but was then three, and is now becoming five… which certainly leaves the door open to the possibility that there will one day be six or 10 or 15 factors! In other words, while the continued addition of factors eventually turns what was once believed to be “alpha” into “just another factor beta”, it doesn’t change the fact that those factors were contributors to alpha before they were recognized as factors, and that could be true of the next factor(s) as well.

Similarly, there’s still not even agreement as to which factors are factors right now; for instance, the Fama-French addition of profitability and investment to their five-factor model just happened, 23 years after the creation of the three-factor model, which itself was several decades after CAPM created the one-factor model, and Carhart (and others) are still maintaining that momentum should be a factor as well (though it was not included in Fama-French). So while in another 20-30 years we may conclude that the next great investment manager’s outperformance was simply the result of a yet-to-be-identified factor (as of today) that will simply be classified as beta thereafter, it’s still potential alpha by today’s standards. As long as we don’t agree on what “the” factors are, those who figure out the next factor successfully before the rest of the investment community agrees will have an advantage. Alternatively, to the extent a factor turns out to be arbitraged away over time – perhaps because “everyone” really does invest it successfully – there may be opportunity in figuring out which factors will and will not persist in the future. (Though notably, the increasingly predictive nature of more multi-factor models suggests that, while there are still “anomalies” that may become new factors in the future, their magnitude and potential for alpha may be limited, as there’s only “so much” left not already captured by the currently-recognized factors.)

Also notable in factor investing is the fact that any one factor in particular may go in and out of favor over time; mathematically, it’s the varying impact of the factors over time that allows them to be identified, and contribute to a more robust multi-factor model in the first place. But this also means that at least in theory, investment strategies that rotate in and out amongst factors (or across asset classes as a means to increase/decrease factor exposures within each asset class) may still have an opportunity to generate alpha.

In other words, while the value factor may replicate much of the “alpha” of value investing, and the “profitability” factor may explain the alpha of Buffett, and the baseline “market” factor provides broad-based market beta, knowing when to overweight value versus profitability versus being in or out of the market at all can still create the opportunity for alpha. For instance, the small and value factors were rewarded heavily in the early 2000s, but momentum was the winning factor of the 1990s, and profitability was the mainstay through the financial crisis. Owning the “right” factor at the “right” time can be more valuable than just owning a diversified portfolio of all of them. Of course, the notable caveat is that thus far, such “tactical” or “dynamic” asset allocation strategies haven’t had a great track record (though as Sharpe noted, that wouldn’t be expected in the aggregate, either, and few funds have really been designed to invest in this exact manner, at least so far); nevertheless, the “meta” factor of making good decisions about when to own the factors could itself be an alpha opportunity.

In any event, Swedroe and Berkin certainly make the case that if anyone is going to invest in an active manager (and pay for his/her services), it needs to be one whose portfolio design materially differs from what could be achieved by just owning an index fund, and/or with other passive factor-loading strategies. In other words, not only is it bad to own a “closet index” fund with low active share, but it’s bad to invest with and pay an active management fee to a “closet factor-loader” as well – a fund manager whose outperformance may beat a benchmark, but doesn’t beat a properly-factor-loaded benchmark. At least, unless that fund manager is dynamically changing the factor exposures over time, and that is the active management value-add.

The bottom line, though, is that a review of the research covered in Swedroe and Berkin's "The Incredible Shrinking Alpha" certainly puts active managers on the defensive to justify where and how they truly add value, beyond what can be achieved by increasingly sophisticated portfolios that are simply designed up front to (passively) capture the rewards of the recognized risk factors. Of course, the active management industry has already been struggling in recent years, with an increasing amount of dollars flowing to index funds and passive strategies. Yet that’s the whole point of “The Incredible Shrinking Alpha” – that such a transition is not merely a coincidence, but the natural outcome of too many expensive investment managers chasing a finite and shrinking pool of alpha in the first place.

The bottom line, though, is that a review of the research covered in Swedroe and Berkin's "The Incredible Shrinking Alpha" certainly puts active managers on the defensive to justify where and how they truly add value, beyond what can be achieved by increasingly sophisticated portfolios that are simply designed up front to (passively) capture the rewards of the recognized risk factors. Of course, the active management industry has already been struggling in recent years, with an increasing amount of dollars flowing to index funds and passive strategies. Yet that’s the whole point of “The Incredible Shrinking Alpha” – that such a transition is not merely a coincidence, but the natural outcome of too many expensive investment managers chasing a finite and shrinking pool of alpha in the first place.

So what do you think? Is the available pool of alpha really finite and shrinking? Does the availability of factor-based investing make the search for active manager who can deliver alpha an increasingly futile effort? Or does it simply necessitate the search for a new kind of manager? If factor-based investing is passive but doesn't use cap-weighted indices, would you call it "smart beta" or something else?

If you accept the assumptions upon which the book is based then it is a real tour de force (and you may do a better job of presenting the key arguments that the authors). However, “factors” are retrospective average asset characteristics based upon linear repressions, and when applied to investors who apply an identifiable style explain very little since the factor exposure of these managers in fact change (sometimes radically and repeatedly) and it is the changes that are interesting (since the process itself does not change).. Relative to the actual irrevocable decisions

of the managers (which at the point of decision were one of many possibilities), the factors are just footprints in the sands of time. The real difference is probably not well presented as “active” vs. “passive”, but might be thought of as “quantitative”–data dependent– vs. “fundamental”–security analysis–and the popularity of indexing should lead to greater opportunities for a process which in effect uncovers accounting errors and misconceptions. In the case of the baseball analogy, there would be lots of .400 hitters if batters were given unlimited opportunities to swing (or not)–no walks and no called strikes, which allows patient investors to wait for what Buffet calls a “fat pitch.”

Until there is zero return dispersion within and across asset classes there will always be opportunities to generate alpha.