Executive Summary

Welcome to the July 2024 issue of the Latest News in Financial #AdvisorTech – where we look at the big news, announcements, and underlying trends and developments that are emerging in the world of technology solutions for financial advisors!

This month's edition kicks off with the news that AI meeting support solution Jump has raised $4.6 million in venture capital, as meeting support has increasingly shown itself as a leading use case for AI as it applies to financial advisors given the sheer amount of time advisors spend on meeting preparation and follow-up tasks between multiple systems and the ability of AI tools like Jump to quickly scan through meeting notes and transcripts and produce meeting summaries, draft follow-up emails, and assign tasks.

From there, the latest highlights also feature a number of other interesting advisor technology announcements, including:

- Digital prospecting solution AIdentified has raised $12.5 million in Series B funding as it looks to further develop and scale its solution for finding qualified prospects for referrals among an advisors' network in order to drive more organic growth – though it remains to be seen how many advisors are ready to engage in a more proactive prospecting approach to the extent that it makes sense to adopt a new technology solution for doing so.

- AI-driven investment research solution Brightwave has raised $6 million in seed funding for its digital "investment analyst" – although in a tech landscape where solutions tend to cater either towards 'active' advisors who seek out investment opportunities on their own or 'passive' advisors who focus more on educating clients to keep them in the markets, it isn't clear where on the divide Brightwave lies (or whether advisors will want to pay for a solution that seeks to do both, given that most advisors fall in either one camp or the other)

- The state of Missouri has joined Washington state in scrutinizing advisors' use of third-party technology like Pontera to access and trade in clients' held-away accounts – which on the one hand, is striking in that those tools seem to be widely popular among clients and advisors alike due to their ability to give advisors secure access to client accounts, making it confusing that regulators would choose to scrutinize them; but on the other hand may be understandable given how quickly the technology to trade held-away assets has emerged, leaving regulators to find any way they can to pump the brakes on further development until they can come up with an acceptable regulatory framework

Read the analysis about these announcements in this month's column, and a discussion of more trends in advisor technology, including:

- A new technology solution, RIA Growth Catalyst, has launched as a tool for firms to identify potential Mergers & Acquisition partners by using current and historical public Form ADV data to gauge which firms actually have a solid track record of organic growth and productivity metrics

- A new survey shows that around 21% of advisors use direct indexing in their practice, which on the one hand, indicates that a large majority of advisors and clients aren't yet sold on the tax efficiency and other benefits of direct indexing (at least enough to make up for the added complexity it introduces), but on the other hand reflects how at least some advisors see direct indexing as a way to more effectively serve high-net-worth clients and values-based investors, leaving the question about whether it will eventually see more widespread adoption than those specific use cases

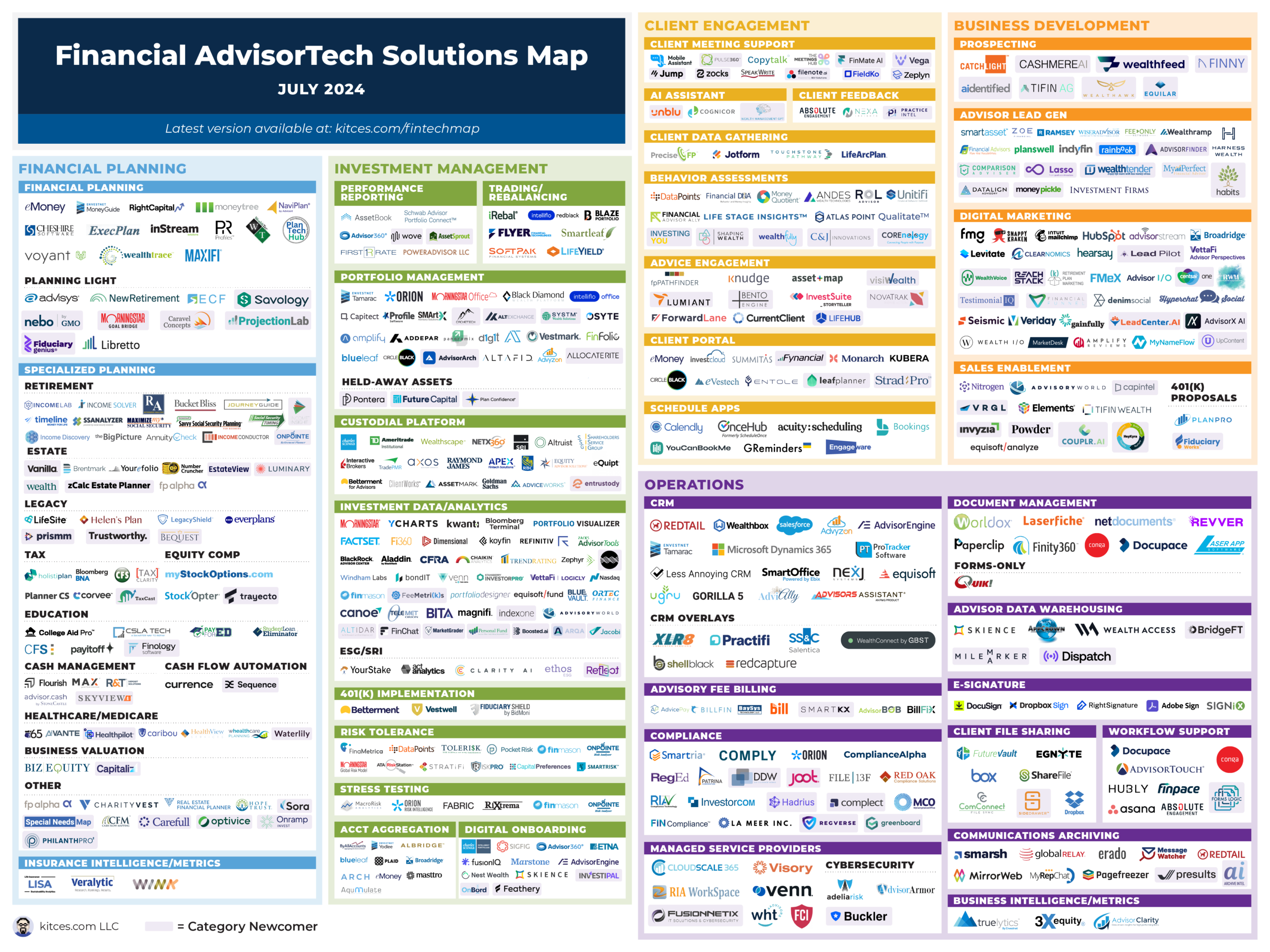

And be certain to read to the end, where we have provided an update to our popular "Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map" (and also added the changes to our AdvisorTech Directory) as well!

*And for #AdvisorTech companies who want to submit their tech announcements for consideration in future issues, please submit to [email protected]!

Jump AI Raises $4.6M As AI Client Meeting Support Gains Traction Among Advisors

One of the challenges with giving financial advice at scale is that the more clients an advisor has, the harder it is for them to keep track of the details of each client's situation: What issues they're facing, what strategies have been recommended to them, what actions they need to take next, etc. Which means that each time an advisor meets with a client, they need to spend significant time on meeting preparation just to get up to speed – and indeed, according to the most recent Kitces Research on the Financial Planning Process, meeting preparation (and subsequent follow-up) takes up about as much of advisors' time as the client meetings themselves.

That time spent on meeting preparation and follow-up is valuable, in a sense, in that it helps the advisor refresh themselves on the details of the client relationship, their financial planning issues and challenges, and the status of any outstanding items from the previous meeting, which is a necessity for an advisor managing dozens (if not 100+) client relationships, who can't necessarily be expected to keep all of that information in their head at all times. After the meeting is over, it's important to archive meeting notes, assign follow-up tasks, and send the client at least a summary of the meeting's key takeaways to keep the momentum going and make it easier to prepare for the next meeting.

But despite the importance of meeting preparation and follow-up, the process that most advisors have for doing these tasks is far from efficient. Advisors usually have client data across multiple systems (CRM, financial planning software, performance reporting, email, etc.), which means poring over the client's details, and the advisor's interactions with them involves pulling together a dispersed set of data in a coherent way. And the problem repeats itself after the meeting, when advisors need to go back to all of those systems to make updates and kick off the required follow-up tasks. Which is ultimately what makes meeting preparation and follow-up so time-consuming because while it doesn't necessarily take a long time to review prior meeting notes or write a summary email, what does take time is managing the manual tasks of data entry and retrieval among the various systems involved.

The glaring inefficiency of the meeting preparation and follow-up process make it an obvious use case for the generation of AI technology that, having emerged following the introduction of ChatGPT in late 2022, has only recently begun to find specific areas where its capabilities align with actual problems needing to be solved. The realm of meeting support, where so much of the information is in written form (or spoken and transcribed into written text), from client CRM data to meeting notes to post-meeting emails to the meeting transcription itself, is particularly conducive to the Large Language Model (LLM) format used in most of today's AI products, which are at their core all about taking text-based inputs and turning them into coherent and (to varying degrees) accurate outputs.

In that vein, it's notable that Jump, one of what has become an eruption of AI-powered meeting support tools in the AdvisorTech landscape over the last year, has raised $4.6 million in venture capital as it continues to build out its AI assistant tool. As a financial advisor-focused solution (rather than a general-purpose AI meeting note tool like Fireflies or Fathom AI), Jump integrates into leading advisor CRM systems like Wealthbox, Redtail, and Salesforce to create pre-meeting prep summaries, log meeting notes, compose follow-up emails, and assign tasks to team members – which for busy advisors has the potential to save several hours per week spent on manually moving information across systems.

Notably, AI meeting note tools won't necessarily eliminate the tasks of meeting prep and follow-up entirely – advisors still need to read the summary to get up to speed on the client, and likely to review edit the follow-up email before sending it. But the point of these tools is to get the whole process done faster, and if AI automation can even cut the meeting prep and follow-up time in half, that would amount to a savings of 5%-10% of their total working time, or over 200 hours per year – which, if the solution works as advertised, could be easily worth Jump's $100+ per user monthly subscription fee.

As meeting notes (and more broadly, everything that goes into meeting preparation and follow-up) has quickly become the hot category of AI as it applies to advisors – spawning not just Jump but also Zocks,Finmate.ai, Vega, Filenote, and FieldKO– the question remains which competitor will ultimately win the race for user adoption and market share. For now, Jump's head start in funding positions it well to continue along the R&D curve to further hone its technology, and to market itself competitively to get advisor attention, while its advisor-friendly features have already won it accolades within the industry. In the end, the question for Jump is whether it can maintain its momentum to separate itself from its competition in a rapidly evolving AI landscape, while for the broader industry, the question is whether (as with any new category) AI meeting support tools like Jump can truly save enough time and deliver enough value to be worth adding yet another piece of technology to the advisor tech stack. Given the sheer amount of time advisors spend on meeting preparation and follow-up, meeting support seems as obvious as an advisor use case for AI as there is – it's now up to tools like Jump to do the job well enough to convince advisors to adopt them.

FactSet Invests $12.5M In AIdentified's AI-Powered "Connection Mapping" Prospecting Tool

Referrals are the lifeblood of organic growth for many financial advisors. According to the most recent Kitces Research on Advisor Marketing, nearly 2/3 of advisors' new clients came as a referral from some trusted source that the prospect already had a relationship with. Whether it's asking a friend or colleague for a recommendation, or a professional like an attorney or accountant, in a world where it's incredibly difficult to find out on one's own which advisors are trustworthy and good at what they do, the majority of consumers look for guidance from people they already know and trust on where to go.

Because of this, financial advisors have long focused on how to generate more referrals, whether that's building relationships with accountants and attorneys, conducting compliant appreciation events as a means for clients to introduce friends and colleagues to the firm, or simply asking clients outright for an introduction to other people they know who would benefit from the advisor's services. The caveat, however, is that as a strategy, the referral-based approach tends to be relatively passive, since it by definition relies on other people to send prospects to the advisor. Advisors can take a more proactive approach and ask clients for referrals, but in reality, most clients struggle to do so, often for the simple reason that they just don't know which of their existing friends or colleagues would be a good fit for the advisor (e.g., they won't necessarily know if their neighbor or coworker can meet the advisor's asset minimums, and it's awkward to ask). Ideally, advisors would already know who in the client's existing network they might want an introduction to, but that requires the advisor to know both who is in the client's network, and of those, who if any would make a good introduction for the advisor.

Meanwhile, in the Internet age, an entire industry has grown up around compiling data on people and their activities, behaviors, and connections and making it available to anyone willing to pay for it, and so it was only a matter of time before digital prospecting tools, using troves of publicly available data to identify opportunities, became a part of the prospecting toolkit for advisors. Big data-driven solutions like Catchlight, Wealthfeed, Equilar, and more recently tools like AIdentified, Wealthawk, Cashmere, and Finny, have all arisen seeking to enhance advisors' ability to identify prospects to more efficiently drive organic growth.

It's notable, then, that this month saw the news that AIdentified has raised $12.5 million in Series B funding from data and analytics provider FactSet, which the company will used to build its team and continue developing its digital prospecting solution.

What's unique about AIdentified is that unlike solutions like Catchlight (which identifies likely-to-convert prospects from an advisor's existing contact list) and Wealthfeed (which tracks "money-in-motion" events involving households that the advisor may or may not have any connection to), it seeks to identify everyone who may be connected to an existing client or anyone else in the advisor's network – creating a 'map' of not just the advisor's direct contacts but also second- and third-order connections. AIdentified also tracks money-in-motion events within the advisor's web of connections, putting it at the nexus between relationship-oriented prospecting (based on warm introductions from people the advisor already knows), and a more proactive approach of reaching out to prospects at the moment a liquidity event such as a home or business sale puts them in need of the advisor's services.

In the industry at large, organic growth among advisory firms has been in steady decline, with most industry studies showing just over 3% in annual organic growth from new clients. Which has created both an immense hunger for mergers and acquisitions among advisory firms (since if you can't grow organically, the next-best path to growth is to grow via acquisition), as well as a significant expansion in digital prospecting tools for advisors looking for new ways to ignite growth. What remains to be seen, however, is how many advisors are actually ready to engage in a more outbound prospecting effort to drive higher organic growth – because, in reality, not every firm is fully in active growth mode, and some advisors may be happy to passively let referrals come to them rather than seeking them out proactively. But Factset's investment in AIdentified at least suggests that there's enough hunger among advisors for organic growth beyond the lukewarm industry-wide numbers to find an appealing value proposition in a solution to find warm introductions to the most qualified prospects in their network.

Brightwave Raises $6M In Seed Funding As An AI "Investment Research Assistant"

It's incredibly difficult to design a portfolio that can reliably beat the market. Professional investors like hedge funds spend billions of dollars in conducting investment research and developing technology that can give them the edge over the competition, which at the micro level has culminated in developments like high-frequency trading firms placing their servers 100 feet closer to the stock exchange in order to get an extra fraction of a microsecond's advantage over their competitors in getting market information, and in the aggregate, has produced markets that are remarkably efficient, so that it's exceedingly difficult for any one investor to do better than the market as a whole.

This has led financial advisors to evolve broadly in 2 different directions. On one side are advisors who work to create their own original views about market opportunities based on deep-dive analysis of market data, and seek to be one of the select few that can prevail over the rest of the market. On the other side are those who believe that the "market" return itself is sufficient for most clients to achieve their goals, and have accordingly adopted a more passive approach to portfolio design. For this second group, there is less time or effort spent on poring over market data that will inform investment decisions (since those decisions are largely dictated by what the market itself is doing), and more time spent on educating clients so they can understand what's happening in the markets and ideally stay on course (and not panic) when volatility arises.

The distinction between these 2 broad investment approaches also shows up in the technology used by advisors in each group. Advisors who try to design portfolios to beat markets often seek to delve deeply into the data to find trends or connections that have not yet been discovered (and thus haven't been arbitraged away), which means the primary challenge of advisors in this group is in collecting and synthesizing enough data from across a wide range of sources to find those heretofore undiscovered insights (particularly when there isn't a dedicated investment research team to delegate that work to). By contrast, advisors who take the more passive approach tend to be more focused on how to educate clients and illustrate what's happening in the portfolio so the clients remain comfortable with their investments, which makes their primary challenge more about efficiently compiling and creating the handful of high-level charts or illustrations that can make the most sense out of complicated market and portfolio dynamics for a nonexpert client.

Into this environment, Brightwave has emerged as an investment research tool that seemingly seeks to cater to both approaches, using AI both to scour and synthesize market data to create investment insights, and to produce client-facing content like market commentary and marketing materials. And this month the company announced that it has raised $6 million in seed funding to expand its 6-person team and invest in new data sources to be used in its software's model.

While Brightwave ostensibly fills a demand among advisors seeking to expedite their investment research efforts – framing itself as a way to "accomplish more, faster" – the somewhat ironic reality is that advisors who do their own investment research tend to do so because they enjoy it, and might not actually want to spend less time doing it (but may welcome a tool that can help them do more research in the same amount of time). At the same time, advisors with a passive approach might not have a need for "more" research – since there's only so much high-level market commentary that can go into a client meeting before it gets overwhelming for the client – but just want a tool that can help them easily communicate the essentials without getting bogged down in market minutiae. In other words, while some advisors might be looking for a tool to help them do more research in the same amount of time, and others might be looking for one that can help them deliver the same level of client-friendly market commentary in less time, there are few who truly need both types of tools. All of which ultimately raises the question about how many advisors will be willing to pay for a solution like Broadwave that caters to both sides of the investment philosophy divide, since in actuality most advisors will likely fall only on one side or the other.

Additionally, given the fact that investment research and data analytics tools like Morningstar, YCharts, and Kwanti have been a staple of the advisor tech stack for years, it's fair to wonder what a generative AI tool like Brightwave is capable of that the incumbent solutions aren't – and if that technology does give them some advantage, whether the incumbents will roll out their own AI research assistants embedded within their popular existing tools. Because there are certainly opportunities in AI tools related to investment research, whether it's helping an advisor get up to speed on a stock or sector by ordering up an AI-generated report summarizing information on multiple sources, or generating a client-friendly market summary around a certain theme. But in an area of the AdvisorTech map with several highly entrenched and well-regarded incumbents, the question is whether new AI-driven tools like Brightwave can hone in enough on where their actual value lies – either as a research tool to help advisors find and test original investment ideas, or as a generator of client-focused investment commentary and summaries – to convince advisors that the tool can enhance their own value proposition enough to make it worth adding another investment-focused tool to their tech stack.

Missouri Sends Warning Letter To RIAs About Access To Held-Away Accounts, Adding To Regulatory Scrutiny Of Popular Data Aggregation Tools

The average American's financial life is splintered among numerous institutions. At any one time, someone may have a bank account for their daily spending, retirement accounts for their current and/or previous employers, investment accounts with brokerage firm, credit cards and a mortgage at another bank, and so on – and for many of these assets, it's common to have multiples of the same type of account spread across different financial institutions. Which means that for the average household, it can be remarkably difficult just to understand what's out there and what it all adds up to, which in turn creates a challenge for advisors in giving holistic advice about what to do with all those assets.

In the 2000s and 2010s, a generation of account aggregation tools arose which, while not exactly solving the problem of having a scattered array of financial accounts, at least made it easier to view them all in one place by pulling data from every account together into a single financial dashboard that kept itself continuously updated (originally by literally logging in as the client and then "scraping" account information from the institution's user interface, and later by back-end API integrations). Although the earliest aggregation tools like Mint were consumer-facing, it wasn't long before account aggregation became a central part of many advisor-facing technology tools, from Mint-like personal financial management dashboards embedded in financial planning software to investment performance and custodial billing software powered by back-end aggregation providers like Yodlee and ByAllAccounts.

The fundamental value of these aggregation tools for advisors was that they provided a secure way to access clients' account information in real-time. The alternative method – collecting the client's login credentials for each site and logging into each website as the client to pull the needed information – represents a security and compliance nightmare, as not only would it be a challenge for advisors to securely store their clients' login credentials, but in the eyes of many regulators merely possessing client credentials can amount to having custody over client assets. In contrast, with most aggregation tools, the client themselves enters their credentials into the system once (where they can't be accessed by the advisor) and grants the tool access to their account data for the advisor and client to view.

In more recent years, however, a key development in account aggregation has been tools that not only allow an advisor to view client accounts, but to actually trade in accounts held outside the advisor's custodian or broker-dealer. Starting with Pontera and more recently with Future Capital, technology tools have built on the account aggregation approach to allow advisors access to make trades in 401(k) and other employer plans, effectively allowing the advisor to manage held-away client accounts that previously had been outside their purview. And while regulators seemed to have had few concerns about account aggregation tools when they were predominantly "read-only" in nature (maybe out of sheer relief that such tools removed the temptation for advisors to collect client credentials and log in to client accounts directly), some regulators now appear to be questioning advisors' use of third-party tools to access and actually trade in clients' held-away accounts.

To that end, it's notable that Missouri has become the latest state to scrutinize the third-party tools that advisors use to manage held-away assets, which comes on the heels of Washington state's crackdown on advisors' use of Pontera in late 2023. Missouri's action came in the form of a warning letter reportedly sent this month to around 45 state-registered RIA firms which, unlike Washington's crackdown which targeted Pontera specifically, broadens the scope to apply to all tools used to access outside accounts using client credentials – that is, even those used solely to view account information, not to directly trade in them.

What's most striking about these concerns is that in the vast majority of cases, allowing third-party access to client accounts is the most client-friendly, and client-secure, solution to sharing information with an advisor. Allowing an advisor to see real-time account information cuts an immense amount of time from the information-gathering process, which in turn improves the advisor's ability to give holistic financial advice while also reducing the cost of providing that advice. And from a client's perspective, allowing an advisor to trade in their 401(k) plan arguably isn't any different from giving them discretionary trading authority in their other investment accounts; in other words, if the client wants the advisor to manage their investments, why shouldn't they be able to manage all of their investments? In turn, to the extent that clients do want their advisor to manage it all, it's arguably far better to entrust the handling and storage of client credentials to a trustworthy third-party company that specializes in exactly that, rather than an advisor collecting passwords on their own while risking numerous security and custody issues.

At the same time, however, the regulators do have a valid point about the particular ways that such data and execution access for advisors is being executed. For instance, as Washington state's commentary pointed out, allowing advisors to access client accounts at outside financial institutions can in some cases constitute a violation of those institutions' own terms of service, which understandably ban the use of third-party client credential sharing to ward off the potential for data breaches or other events to cause liability issues for the institution. Which means advisors encouraging their clients to use third-party aggregation tools that are built around credential-sharing to log in as the client can effectively make the advisor complicit in violating financial institutions' terms of service. Such that regulators don't want to condone that behavior, even if clients happily agree to share their credentials and arguably benefit from doing so.

From a broader perspective, however, the scrutiny of Pontera and other aggregation-based tools may be less about the terms-of-service issues and more of a reflection of regulators' discomfort with the screen-scraping approach that they were originally built around. Which only becomes more concerning when the use cases progress from a relatively innocuous "view-only" tool to a much higher level of capability, where advisors are able to trade in (and bill on) client accounts outside of the highly-regulated custodial framework. Perhaps as regulators labor to assess the risks of third-party account access and distinguish what constitute permissible uses of account aggregation with those that are more problematic, they've found in the terms-of-service issues a way to pump the brakes and keep the situation from progressing any further before they can settle on an acceptable regulatory framework?

In the longer term, the current standoff can most likely be resolved by financial institutions agreeing to share direct API integrations with approved third-party tools to enable functions like trading, similar to how account balance, transaction, and other data points have already been heavily shifting to an API-based approach that doesn't require credential sharing (and thus can be managed within institutions' own terms of service). Although that approach comes with its own set of questions, such as how much it will cost to build and maintain those integrations, and how much of that cost will be passed downstream to tech vendors, advisors, and clients themselves.

But ultimately, it remains to be seen if Missouri and Washington end up as regulatory outliers in questioning advisors' use of third-party tools to manage the security of getting access to clients' held-away accounts (either to get data, a la account aggregation, or to engage in more proactive tasks like trading), or if other states and/or the SEC start to raise their own concerns such that advisors' use of Pontera and similar tools is seriously thrown into question. In the meantime, however, regulatory friction around data aggregation may simply be the cost of living in our splintered financial world. Technology can come up with a solution to patch everything together quickly, but it takes time and money to build something that satisfies the interests of not only advisors and their clients but also financial institutions and regulators.

RIA Growth Catalyst Launches As A Data Engine For RIA Acquirers

Organic growth has always been a challenge for advisory firms, and it's only gotten harder in the last 5–10 years. In part, the challenge is around marketing: There are simply more advisory firms providing comprehensive financial planning services than there were in the past, meaning financial planning itself is not the differentiator that it was in the past. Similarly, many firms have switched from commission-based models to fee-only, making compensation model less of a differentiator as well. And on the whole, it's getting more and more difficult to find a prospective client who doesn't have an advisor at this point, especially as institutions increasingly employ strategies (such as the 2018 merger of Edelman and Financial Engines) that integrate advisors into 401(k) plans, meaning fewer employees at those companies end up looking for outside help.

In general, advisory firm owners have taken 1 of 2 approaches to the challenge of achieving organic growth. Either they invest in marketing, lead generation, or other ways to spur natural organic growth in a competitive market; or they decide that if they can't grow organically, they'll grow through Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A) instead.

The problem for many firms that have gone down the M&A path (and for the private equity firms that often back these deals) is that it's difficult to get an adequate return on the dollars invested in M&A if the resulting firm can't figure out how to achieve its own organic growth. In practice, many of the largest acquirers of advisory firms have ended up with diminishing valuations as they've struggled to either ignite their own growth after the acquisition, or to at least acquire firms with their own solid organic growth rate that can be sustained in the new enterprise. In other words, while a firm can always grow by tacking on more acquisitions, the resulting conglomeration will never be worth more than the sum of its parts unless it can either learn how to grow itself, or bring in enough high-growth acquisitions to move the needle.

It's notable, then, that this month a new startup has emerged specifically to tackle the challenge of identifying acquisition targets for achieving growth through M&A. Dubbed RIA Growth Catalyst, the tool culls through both current and historical firm regulatory data (as listed in public Form ADV filings), allowing it to identify firms with proven organic growth of assets and (especially) clients, and which have healthy productivity metrics as measured by common ratios like per-employee and per-client AUM.

At a high level, RIA Growth Catalyst may only be relevant to a small subset of advisory firms that are committed to a serial acquisition strategy that makes it worth investing $10,000+ into technology to identify a stream of optimal-fit acquisition targets. Yet for the few firms this does apply to, RIA Growth Catalyst appears to be positioned in unique ways by being able to reflect historical growth metrics, as well as to hone in on other metrics like client types and publicly disclosed investment holdings.

So while the market for a tool like RIA Growth Catalyst might not be huge in terms of the number of firms it reaches, it has the potential to be very valuable to those that it does apply to, by allowing acquirers to identify firms that – by their own regulatory disclosure – have a solid track record of organic growth and align with the acquirer in terms of client composition and investment approach. (With the caveat, however, that finding 'good' acquisition targets doesn't mean those targets actually want to be acquired – indeed, the owners of many high-growth firms might be uninterested in acquisition, other than a few that might be willing to 'tuck in' and continue to focus on growth without having to worry about the operational challenges of scaling up the firm.)

In the end, however, the financial advisory industry's M&A boom is unlikely to end anytime soon, as evidenced by the continued flow of PE dollars into the RIA channel. However, the length of the current cycle means that most of the 'low-hanging fruit' of straightforward acquisition targets has largely been gobbled up, which means that increasingly sophisticated acquirers will need to be more nuanced and selective in finding firms that are worth the investment. Ultimately, that positions RIA Growth Catalyst well for being the data source for the few dozen firms that appear committed to the strategy.

Study Shows That 21% Of Advisors Use Direct Indexing, But Will It Achieve Mainstream Adoption Beyond 'Just' Tax- And Values-Focused Advisors?

About once every 20 years, a new vehicle for investing emerges that changes the way financial advisors build portfolios for clients. While advisors had their roots in selling stocks and bonds for clients in the 1960s and 70s, individual securities largely gave way to mutual funds in the 1980s and 90s, which themselves were largely supplanted by ETFs in the 2000s and 2010s. Notably, none of these vehicles were exactly brand-new by the time they became widely used by advisors: Mutual funds have been around since the 1920s, and ETFs since the early 1990s. But while they may not have seemed like an improvement over the status quo when they debuted, they each gradually grew in use until they became what seemed like the obvious default choice as the building block for portfolio construction.

Direct indexing, which has itself been around in some form for over 20 years, has for a number of years now been seen by some as the future of investment management. Originally employed only by a few specialized managers for ultra-high net worth clients, more recent developments like automated rebalancing, commission-free trading, and fractional shares have both drastically reduced the cost of direct indexing and made it feasible to implement for a much higher number of households and smaller accounts.

To its believers, direct indexing has the potential to do to ETFs what ETFs did to mutual funds before them by becoming the new paradigm in portfolio management. Because in theory, direct indexing eliminates the need for investors to buy an off-the-shelf investment vehicle since at the click of a button they can simply allocate an individual stock portfolio that holds all the same components of an index fund without the cost of the ETF or mutual fund wrapper, while at the same time being more tax-efficient (since direct indexing allows for tax-loss harvesting at the individual security level instead of the fund level) and allowing for client-specific modifications like adjusting the portfolio to fit within client-specified values or ESG parameters or allocating around a client's concentrated stock holdings.

At the same time, however, there are practical challenges around direct indexing that have limited its adoption so far. While mutual funds and ETFs each arguably represented a more simplified portfolio management approach than their predecessors, where advisors could pick 1 or 2 broad-based funds per asset class to build a portfolio of 'only' 5–10 holdings representing nearly all investable public markets, direct indexing is significantly more complex due to its vastly higher number of holdings, continuous tax-loss harvesting (and subsequently more complicated tax reporting), and the requirements of monitoring the software to ensure it does its job and manages the portfolio to its specified parameters (which presents an additional compliance burden for advisors who promote the benefits of their direct indexing strategy and need to subsequently ensure that their software does what they say it does). And at a base level, it's simply a tougher sell for advisors who have worked for decades to internalize in their clients the appeal of a simplified investment approach, only to be told that the future of investing lies in a model that involves constantly monitoring and trading hundreds of individual securities. Not to mention that direct indexing providers want to earn their own revenue for providing the platform or trading service… which in many cases is more costly than a low-cost index ETF they might have replaced. Which means direct indexing 'only' works if the tax-loss harvesting, portfolio customization, or other client benefits, can exceed a potentially higher cost.

All of which helps to explain why a recent industry study by FTSE Russell highlights that 'only' 21% of advisors are using direct indexing in their own advisory practice. Notably, the survey's sample population of 631 advisors, all of whom had at least some familiarity with direct indexing, might not be representative of the industry at large (in other words, 'true' adoption across all advisors is likely lower). But if we compare the Russell study's 21%-adoption-rate findings with FPA's most recent Trends in Investing Report (which doesn't break out direct indexing as its own category but presumably lumps it in within Separately Managed Accounts), direct indexing would fall behind ETFs, mutual funds, individual stocks and bonds, ESG funds, and fixed and variable annuities in terms of products used by advisors – but slightly ahead of private equity, structured products, options, and cryptocurrency.

So while direct indexing has certainly seen some pickup among advisors – and notably, 48% of the advisors in the Russell survey stated that they planned to try direct indexing in the next 5 years, meaning it's still potentially poised for further growth – it has a long, long way to go to dethrone ETFs in terms of advisor adoption. However, advisors do at least seem cognizant of direct indexing's benefits from a tax perspective, and with the increasing emphasis by financial advisors on the tax value of their advice, the ability to efficiently integrate tax-loss harvesting into the investment management process could boost direct indexing's adoption, particularly among advisors of high-net-worth clients for whom investment income really does pose significant tax issues. But still, the enthusiasm for direct indexing hasn't trickled down to the client level, with 34% of advisors in the FTSE Russell survey citing a lack of client demand as a reason for not implementing direct indexing, and just 7% of advisors in the FPA study indicating that any of their clients have inquired about direct indexing over the previous 6 months… meaning that for all its potential benefits, at best advisors have to "sell" those direct indexing benefits to differentiate themselves, because very few clients are coming in asking for it.

For now, the debate around direct indexing is really about whether it truly has the potential to become a mainstream alternative to ETFs and mutual funds, or if it will remain within its current niche as a more specialized offering for a number of distinct (but definitely-not-for-all) use cases. For advisors of high-net-worth clients for whom the tax benefits of direct indexing are particularly valuable (and who are already accustomed to a high level of complexity in their financial life), direct indexing could certainly become a standard offering, even as just a sleeve for the subset of clients who have taxable accounts that would most benefit from it. And for the relatively fewer advisors who specialize in values-based investing, the customization capabilities of direct indexing can allow for a much more personally-aligned portfolio than an off-the-shelf fund, at less expense than an actively-managed SMA.

In any of the use cases, though, direct indexing is less a story about changing the way portfolios are managed, and more a story about technology making it feasible to enact a specific approach at the scale of a client base, and so like any technology, whether or not it's widely adopted depends on how much it improves advisors' ability to deliver advice, scale their operations, and grow their business. For advisors who have a critical mass of tax-sensitive high-net-worth clients or a specialization in values-based investing, direct indexing may well fit in with that value proposition – but elsewhere, it remains to be seen if the potential benefits are enough to overturn the decades-long trend towards overall simplification in investing.

In the meantime, we've rolled out a beta version of our new AdvisorTech Directory, along with making updates to the latest version of our Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map (produced in collaboration with Craig Iskowitz of Ezra Group)!

So what do you think? Is client meeting preparation and follow-up enough of a pain point to adopt an AI meeting support solution? Do regulatory concerns put the future of held-away asset management tools like Pontera in doubt? Do the tax and customization benefits of direct indexing make it worth the added complexity? Let us know your thoughts by sharing in the comments below!

Leave a Reply