Executive Summary

The modern form of retirement – a period of non-work that you can and must enter because you’re no longer able to work – is itself a rather modern phenomenon, and one that ironically became both more feasible and more necessary as life expectancies increased over the past 100 years. Because when coupled to the industrial revolution and the shift from farms to factories, rising longevity became both a business and societal necessity to figure out what to do with the “obsolescent” human beings who couldn’t productively work anymore, but still needed to support themselves!

Yet as life expectancies and medical science continued to advance, we reached the point where retirement wasn’t just a stage of being unable to work, but instead a stage of being able to enjoy a period of non-work leisure. The only requirement was to save and invest enough to be able to afford to not work. Which in turn led to those who tried to reach the threshold earlier and earlier, younger and younger, until the “Financial Independence, Retire Early” (FIRE) movement was born.

But the challenge of trying to “FIRE” out of work as quickly as possible – sometimes as early as one’s 40s or even 30s – is that it leaves a very long time to be in “retirement.” So long, in fact, that the classic “4% rule” of retirement should probably be more like a 3.5% rule (given the extended time horizon). But also so long that most human beings will struggle to be idle for so long… which often leads back to productive engagement that even ends out producing post-retirement employment income. Which ironically means that if many of those accumulating towards FIRE considered this likely income, they might even transition sooner instead! (Because even earning “just” $20,000/year of side income in retirement can reduce nearly $500,000 from the required retirement savings!)

And ironically, despite the focus on accumulating enough assets to FIRE (often as quickly as possible), the real challenge is that while sequence of return is a real risk, it is more often a great boon. In fact, while a 3.5% initial withdrawal rate is necessary for the one worst sequence… 50% of the time, a FIRE retiree at a 3.5% initial withdrawal rate finishes with more than 9X their starting principal left over!

Which suggests the real key, especially for the kinds of extended time horizons that FIRE retirees face, is to develop more flexible spending rules that can adapt to whatever markets (or post-retirement income) may bring. Because while 30-year retirement time horizons have both some upside and downside risk, 40-50+ year time horizons end out with extraordinary upside potential… if only the retiree can weather any potential initial storm. Creating options to ratchet spending higher over time, to create spending “guardrails” to remain in a safe zone, or to segment expenses to ensure the essentials are covered but allow more adaptive lifestyle expenses to creep higher over time (as it will likely be feasible to do!).

In the end, though, the key point is simply to understand that, with extended retirement time horizons under FIRE, it becomes necessary to be more conservative against the potential worst-case scenario, but flexible to the overwhelming number of more positive scenarios likely to occur. Especially when considering that most retirees will struggle to remain “idle” for 40-50+ years (especially when retiring in their early still-productive years). The good news is that more flexible spending rules create many options to still adjust spending dynamically along the way. The problem is simply that they’re arguably the area that most needs to be studied further, to determine spending rules that are both comfortable to manage lifestyle and spending expectations, and really can weather the adverse-returns storm should it happen to come!

The Problem With FIRE: Human Beings Aren’t Meant To Be Idle For Life

For most of our history as human beings, a safe “retirement” simply meant having enough children to farm the land when you were no longer able to. It was only over the past century or two – with the industrial revolution and the move from farm to factory – that the more modern concept of retirement began to emerge. A world where humans were workers who earned wages to buy the necessities of life… right up until they couldn’t work anymore, and as “obsolescent factory equipment” had to be “retired” from the factory.

Which meant, in essence, that saving for retirement was simply about being able to financially support yourself after you were retired into obsolescence. And in turn led to the creation of social safety nets – like Social Security – to help protect those who older workers were "obsolescent" and unable to work, but who hadn’t saved enough to support themselves.

It was only in the mid-1900s that the financial services industry really attached onto the concept of retirement, and began to morph it from being not just a stage of obsolescence (where you hopefully had enough to get by), but as a stage of post-work leisure that you wanted to work towards, and where you would save enough that you could not just get by, but actually enjoy retirement. (And, hopefully, save in the financial services industry’s investment and annuity products in order to get there!)

Of course, once retirement is about saving enough to retire – instead of simply retiring when you have to because you can’t work anymore – a natural opportunity emerges: to save more, faster, and retire even earlier. In other words, once achieving retirement and a life of leisure was simply about saving enough in order to do so, it was only a matter of time before at least some people would make it a goal to reach that financial threshold as quickly as possible. And thus was born the Financial Independence/Retire Early (or FIRE) movement.

The problem, however, is that even as the FIRE movement develops strategies to reach financial independence earlier and earlier, to have a longer time window for that life of leisure… retirement research is finding that even "normal" retirees often aren’t nearly as happy in that retired life of than they expected!

Instead, retirement is associated with everything from the rise of Gray Divorce (divorce rates amongst those ages 65 or older has tripled in the past 25 years), to increased isolation that can lead to depression and other health complications, along with the birth of “encore careers” and the numerous ways that retirees are figuring out to (re-)engage themselves in retirement to avoid these adverse outcomes… which, ironically, often includes an income component, as retirees take new/different jobs, start new careers, or even start new businesses altogether. In fact, recent research suggests “retirees” in their 60s actually have the highest rates of entrepreneurship and business ownership in America, and those who retire (FIRE) earlier may have even more entrepreneurial potential (as entrepreneurial success rates peak for founders that start around age 40).

In other words, FIRE is arguably less about “Retire Early,” and more about simply achieving “Financial Independence”… which doesn’t mean a world of not working, but simply a world where the choice of what to do with your time happens to be independent of the need to generate financial income. Because retiring early implies a life of indefinite leisure vacation... even though, as Anna Rappaport recently put it, “You can’t be on vacation all the time. Vacation is a break from what you normally do. People who retire with the idea of an endless vacation are likely to be disappointed or bored within a year or two, if not sooner.”

All of which is incredibly important, because even just modest levels of income can drastically change how much is needed to “FIRE” in the first place!

For instance, the common rule of thumb is to use the 4% rule to FIRE (i.e., that it’s safe to retire early when you have 25X your expenses saved up). Thus, for someone that spends $40,000/year, they’ll need $1M to FIRE (retire early); those spending $80,000/year need $2M.

Except what happens if that early retiree realizes he/she will earn “just” an average of $10,000/year in “retirement” for the next 40 years after all? It cuts down the net spending need by $10,000/year, which reduces the required savings to FIRE by $250,000! And what if the part-time income after financial independence is $20,000/year? It cuts $500,000 – a half million dollars – off the required savings, just by recognizing some post-Financial-Independence income will likely still be there!

(Of course, the retiree may still need to make this up after he/she really can’t work anymore in their later years of retirement, but that’s often a point where discretionary spending is declining… which means the income may no longer be necessary to support the lifestyle at that point anyway!)

How Longer Time Horizons Amplify Sequence Risk – To The Downside And The Upside

On the other hand, while the failure to recognize the potential for post-Financial-Independence income causes many people to save more than they need and wait longer than necessary to FIRE, the caveat is that, for those retiring extremely early – who may have 40-50+ year time horizons – the “safe withdrawal rate” isn’t actually 4% in the first place.

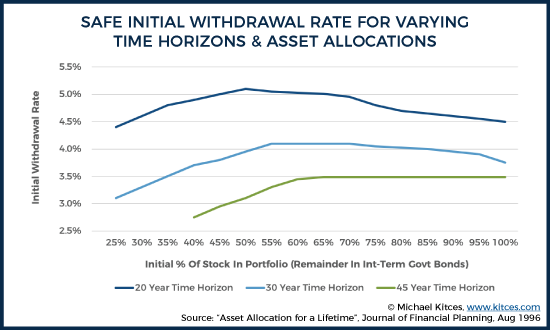

Because the original “4% rule” safe withdrawal rate, first published by Bill Bengen in 1994, was specifically based on a 30-year time horizon. In fact, in a 1996 follow-up to him seminal study entitled “Asset Allocation for a Lifetime”, Bengen himself recognized that the safe withdrawal rate is actually 5% for those with a 20-year time horizon, but only 3.5% for those with a 45-year time horizon.

Notably, decreasing the time horizon by “just” 10 years increases the safe withdrawal rate by 1% (to 5%), but increasing the time horizon by 15 years decreases the safe withdrawal rate by only 0.5% (to 3.5%). Which would turn the classic 25X post-retirement spending target (a 4% rule on your accumulated retirement savings) should perhaps be a 28X rule instead (or 30X for those who prefer to be a little more conservative?).

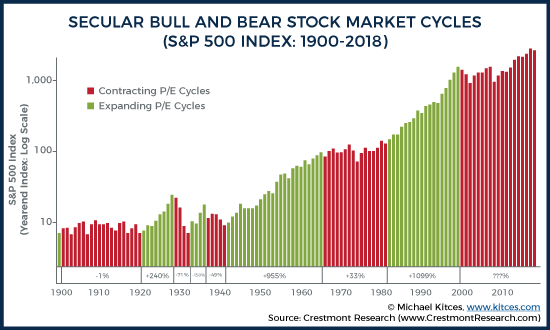

Notably, though, the reason that the withdrawal rate only decreases slightly, even for a much longer time horizon, is that markets themselves tend to move in 10-20 year secular cycles, with extended periods of substantial growth, followed by substantial periods of largely-sideways markets. Which are the cycles that create “sequence of return” risk and necessitate the 4% (or 5%, or 3.5%) rule in the first place. Because even if market returns average out in the long run, if you get there with a bad sequence – 15 years of mediocre returns followed by 15 years of great returns – you can literally run out of money in the bad sequence, before the good returns finally show up to average out in the long run.

Except, given that secular bear markets typically run in roughly 15 year cycles, if a withdrawal rate is low enough to “survive” until the recovery and last for another 15 years (30 total), it doesn’t take much more to survive the same difficult period and then last for another 30 years (45 total). Because the secular bull market cycles are typically so good that they create more than enough wealth at a modest withdrawal rate to weather the next storm that may follow!

In fact, ironically, the real challenge of 45+ year time horizons is that a longer time period increases the upside potential if returns go well, far more than the downside risk if returns are poor! As in scenarios where the sequence is not horrific and doesn’t necessitate needing an initial withdrawal rate of 4% for 30 years (or 3.5% for 45 years), the excess returns above that amount, compounding for 40-50 years, can create absolutely extraordinary upside!

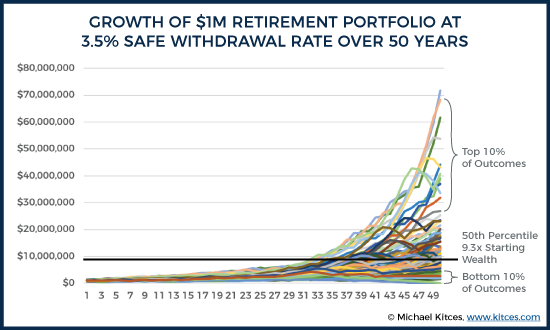

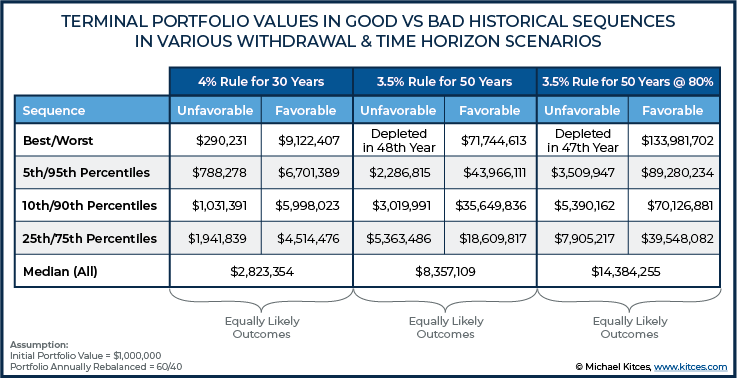

Accordingly, the chart below shows the trajectories of wealth for 50-year retirement time horizons for those FIRE very early with a $1M account balance, at a 3.5% initial withdrawal rate, for a 60/40 annual rebalanced portfolio, through various rolling return periods in history.

As the chart reveals, it is “necessary” to take a 3.5% withdrawal rate for the one scenario that is depleting after 50 years at that rate. Yet with “just” a $1,000,000 starting balance, there is a 90% chance of finishing with over $3,000,000 (or 3X the starting wealth) at the end (i.e., only a 10% chance that wealth is anywhere below $3,000,000, from a $1,000,000 starting point!), and a 50% chance of finishing with more than $9.3M (i.e., 9.3X the starting wealth) left over after 50 years (which would still be more than 2X starting wealth on an inflation-adjusted basis)! In fact, the wealth accumulations are so extreme, it’s impossible to see the one failing scenario that necessitated a 3.5% initial withdrawal rate!

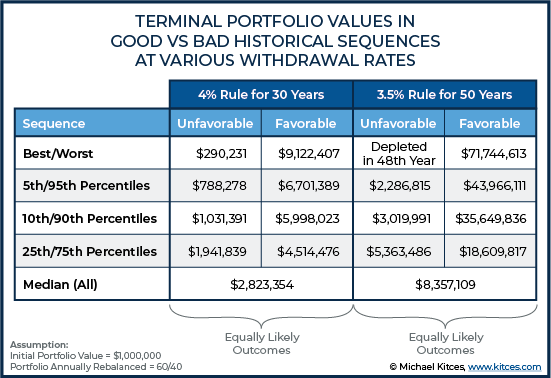

To highlight just how wide the range of outcomes actually are, the chart below shows equally-probable percentile outcomes with both a 4% withdrawal rate for 30 years and a 3.5% withdrawal rate for 50 years.

In fact, the upside potential is so significant after weathering the “initial” speed bump of a mediocre first 15 years of returns, that the results are even better using an 80% equity portfolio instead of “just” 60% in equities. Again, one scenario just barely falls short of the 50-year mark (in this case, a 1966 retiree who had to suffer through the challenging 1970s until the bull market finally arrived)… but 50% of the time, the retiree finishes with almost 15X their original wealth on top!

Why FIRE Necessitates Spending Rules For Adaptive Flexibility

The fact that 40-50 year retirement time horizons create such a wide range of outcomes – with a $1M portfolio equally likely to be depleted, or finish with over $150M(!) in wealth left over – suggests that it’s really not enough to just set a safe withdrawal rate spending target and then cruise forward from there. As at best, doing so creates an overwhelming likelihood of simply leaving “extreme” wealth accumulations left over. Which, in turn, also means that those pursuing Financial Independence might have even been able to retire sooner, or at least lift up their lifestyle sooner, especially when also considering the “unexpected” introduction of post-Financial-Independence income streams from voluntary work.

Of course, the caveat is that there’s still “that one scenario” where financial disaster may occur – or more realistically, a very-extended period of poor returns, such as those during the Great Depression or the 1970s – that can cause even a 3.5% initial withdrawal rate to fail after 50 years. Which means any increase in spending, initially or in subsequent years after retirement, must be accompanied by some means to adapt, in case that one disastrous scenario appears to be playing out.

In other words, the longer the retirement time horizon, the more conducive it is to rules-based spending strategies that change and adapt over time, rather than simply a fixed “anchor” spending level that can become extremely de-coupled from the wealth accumulation reality over time.

Using Ratcheting Rules To Adjust Up When Times Are Good

The first option is to consider adopting a “ratcheting rule.” The idea of a ratcheting rule is to set a spending “floor” that is intended to be relatively impermeable (e.g., a baseline 3.5% initial withdrawal rate for a 50-year time horizon), but with a concrete target for how spending will be increased if/when a disastrous scenario does not unfold and returns are even merely “decent” (not to mention when returns are very good, or additional post-Financial-Independence income comes into the picture). In other words, like a ratchet itself, spending is only meant to turn one direction (increased when safe), but is locked in the other direction (not to be cut), in acknowledgment that most people find it very distressful to cut something out of their lifestyle once accustomed to it. (Thus starting spending more conservatively in the first place.)

In terms of implementing the ratcheting rule itself, one approach is a version previously discussed on this blog: simply track ongoing wealth, increase spending by 10% if the portfolio has accumulated at least a 50% buffer over its original value, and re-check every 3 years. Another option might simply be to re-calculate a 3.5% “initial” withdrawal rate any year the portfolio grows above its high water mark (under the auspices that if it was “safe” at 3.5% in the first place, it should still be safe to reset to 3.5% of a new higher amount, especially as the years go by and the time horizon gets shorter anyway).

Using Guardrails To Keep FIRE Spending In A Safe Range

A second approach would be a “Guardrail” strategy, such as the rules-based spending approach delineated by Jon Guyton in his prior research. The idea of a Guardrail strategy is to set thresholds on either side of the intended withdrawal rate and make spending adjustments any time withdrawals deviate outside that range.

For instance, rather than spending a “fixed” 3.5% initial withdrawal rate (only adjusting for subsequent inflation), the retiree might start spending at 4% instead, but set guardrails at 3% and 5%. Then in each subsequent year, inflation-adjusted spending is compared to the value of the portfolio. As long as the then-current withdrawal rate remains in the 3% to 5% range, spending remains on track. If the portfolio rises more quickly and outpaces spending – such that the withdrawal rate falls below 3% - then the retiree gets a 10% raise to their real-dollar spending. Conversely, if the portfolio falls (or simply lags spending increases) and the withdrawal rate drifts above 5%, the retiree must take a 10% real-dollar cut. Notably, in Guyton’s original methodology, an additional “tweak” is not to take the annual inflation increase any year that the portfolio’s returns aren’t positive –a small-but-permanent cut to baseline spending, which also has a surprisingly large positive impact on helping portfolio spending to adapt to unexpected adverse market sequences.

In essence, the goal of the Guardrail approach is to get spending in a protected channel – at least for the next 20-30 years, until the time horizon is shorter (and withdrawal rates can naturally drift higher).

Of course, the caveat to the Guardrail approach – unlike following a Ratcheting Rule – is that it assumes that spending cuts will occur when the portfolio veers off track from its original withdrawal rate course. Which, unless the guardrails are set extremely wide, is almost a certainty to happen at least temporarily at some point, given market volatility.

And in a sustained period of poor market returns, it’s possible that multiple cuts could occur sequentially/repeatedly over time, which can take the retiree’s standard of living even lower than just having started at a more conservative withdrawal rate. But that’s also the point – for those willing to take cuts along the way, it’s feasible to spend more, and “often” works out… except sometimes it doesn’t, and the guardrails will do what they need to do ensure the retirement accounts aren’t depleted (at the cost of downgrading lifestyle along the way).

Segmenting Retirement Spending To Maintain An Essentials Floor With Upside

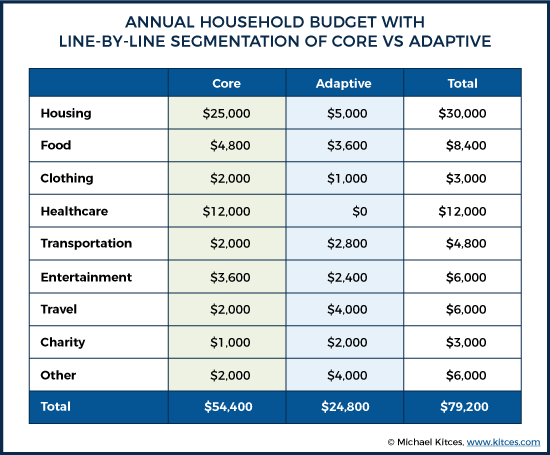

A third approach to manage the FIRE path more dynamically is to segment the spending itself, effectively combining a ratcheting strategy for a spending “floor” with more dynamic guardrails for the more adaptive components of spending along the way.

For instance, a prospective FIRE saver might decide to make the Financial Independence transition when a 3.5% spending rate against their assets is enough to cover the pure essentials – the food, clothing, and shelter kinds of expenses that you cannot afford to outlive, along with the “basic” niceties of life (some form of transportation, simple entertainment, and travel expenses, etc.) – and then allow any portfolio upside, plus any post-Financial-Independence work and the income it generates, to cover and enrich the lifestyle along the way.

The key distinction of this approach is simply to recognize that these more adaptive expenses – eating out more often, at nicer and fancier (and more expensive) restaurants, taking longer and more exotic vacations, buying designer clothes, etc. – are by definition more flexible. They’re the “nice-to-haves” that we may hope for… and in all likelihood, will be able to afford in the overwhelming majority of scenarios where there is not a catastrophic return sequence and/or there is a non-trivial amount of post-Financial-Independence employment income.

In fact, if/when better (or at least non-catastrophic) market returns do arrive, and/or there is additional income, the FIRE retiree would actually have a choice, to increase the adaptive expenses, or to ratchet higher the core lifestyle to a higher standard of living in the first place (e.g., moving to a larger house or a more expensive location, buy a fancier car, etc.).

Nonetheless, expenses are still segmented in a way that ensures the core lifestyle is feasible to afford and sustain even if the upside doesn’t come.

In the end, arguably the biggest challenge in the FIRE movement – and ultra-long-term retirement planning in general – is that we haven’t done enough to develop “rules”, and a framework for rules-based spending adjustments, to know not just what is a safe point to retire, but what is a safe spending path as the subsequent future unfolds. Recognizing that, with 40-50+ years to compound, the range of future outcomes is actually much much wider than more retirees realize (or can even comprehend, with “equal” likelihood of a $1M retirement account running out, or turning into $150M, at a 3.5% initial withdrawal rate!).

Either way, though, a deeper look at the retirement research suggests that, with the 40-50+ year time horizon of FIRE retirees, that the “4% rule” is really more of a 3.5% rule (or to round down a little further for "safety," 30X post-retirement spending may be a better target than 25X as implied by the 4% rule). Though at the same time, it’s equally crucial to remember that the 3.5% withdrawal rate should reflect the intended spending after giving some consideration to whether any post-Financial Independence income will eventually arrive (and that, simply given human nature, it is very likely to come at least for a material subset of FIRE retirees).

Yet again, even with a more accurate initial withdrawal rate, and a better reflection of the likelihood and potential amount of post-FIRE income, the reality remains that even most FIRE retirees will not need to stick with that spending floor indefinitely, most will have some (or a lot) of upside, and that those who are willing and able to be more flexible in their spending actually have the latitude to start with a higher withdrawal rate and spending amount in the first place (as long as they really have the flexibility to make the adjustments if/when/as necessary). Which, ironically, means, that in the end, perhaps the problem isn’t that the 4% rule is too aggressive for an unusually long time horizon, but that it’s too conservative – at least for those who have any comfort and ability to make mid-course adjustments along the way? (But to each their own about their individual tolerance for spending changes!)