Executive Summary

Despite the fact that one research paper recently found Americans are more afraid of outliving their money during retirement than death itself, and economics research has long since shown that leveraging mortality credits through annuitization is an “efficient” way to buy retirement income that can’t be outlived, the adoption of guaranteed lifetime income vehicles like a single premium immediate annuity purchased at retirement remains extremely low.

In a recent new book entitled “King William’s Tontine: Why The Retirement Annuity Of The Future Should Resemble Its Past”, retirement researcher Moshe Milevsky makes the case that perhaps the primary blocking point of immediate annuitization really is its cost, and that guaranteeing mortality credits takes an unnecessary toll on available retirement income payouts (not to mention creating systemic risk for insurance companies if there’s a medical breakthrough!).

As an alternative, Milevsky advocates for an alternative retirement income vehicle, called a tontine. Similar to an annuity, a tontine provides payments that include both a return on capital and mortality credits stacked on top. The difference, however, is that with a tontine the mortality credits are not paid until some of the tontine participants actually pass away – which eliminates the guarantee of exactly when mortality credits will be paid, but also drastically reduces the reserve requirements for companies that offer a tontine (improving pricing for consumers).

Ultimately, it remains to be seen whether consumers would be willing to adopt a payment structure that involves getting more money for outliving your tontine peers. Yet Milevsky’s look through history reveals that tontine agreements have actually been very popular in the past, and nearly 100 years ago the use of tontines by Americans for retirement was similar to the adoption of IRAs today. Which means it really may not be much of a stretch to suggest that they should be brought back as a new form of retirement lifetime income vehicle for the 21st century as well!

What Is A Tontine Agreement?

A tontine agreement is a form of pooled investment fund to which the investors contribute a lump sum and in exchange receive ongoing payments (or “dividends”) as a return on their investment. Similar to a single premium immediate annuity, the payments from a tontine are typically made “for life” and end only at death. However, with a tontine the payments that cease at the death of one investor are redistributed to the other investor participants, increasing their subsequent payouts (until they, too, pass away).

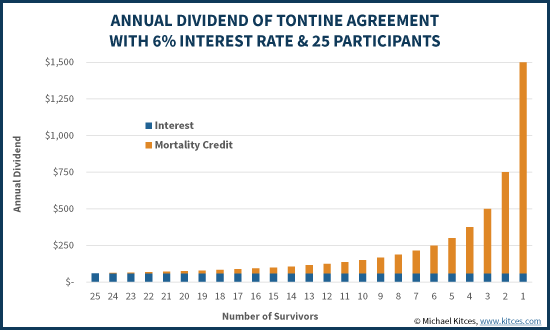

Thus, for instance, if 25 people were to put $1,000 each into a tontine – for a total contribution of $25,000 – and the tontine stipulated that it would pay out 6%, each year the $25,000 principal would generate $1,500 of dividends. As long as all 25 people are alive, each will receive a 1/25th share, or $1,500 / 25 = $60, which is simply equal to a 6% payout on their original $1,000 principal.

However, if after several years only 20 people remain alive, the $1,500 annual dividend (6% of the principal) is now split amongst just those 20 people, resulting in a per-person dividend increase to $1,500 / 20 = $75.

As more people pass away, the tontine payments to the survivors continue to grow (as the same total dividend payment is shared amongst a smaller and smaller pool of people), with the final few participants receiving extraordinarily large dividend payments in their final years (especially relative to their individual investment of only $1,000).

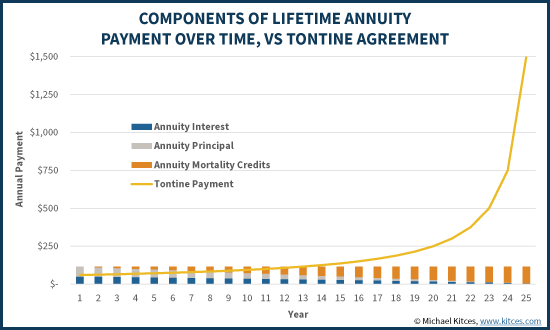

Notably, the concept of redistributing a share of pooled payments from those who pass away to the survivors is not unique to tontines. Such “mortality credits” – which increase the size of distributions beyond what could be paid from principal and interest alone – are also a core aspect of any lifetime annuity product. However, in the case of lifetime annuities, the payments are typically structured to be level – where distributions are technically larger than what the principal and interest alone could sustain, but are done in anticipation of the fact that some annuitants will pass away, allowing their shares to be redistributed in a manner that sustains the level payments. By contrast, with a tontine, the payments start out smaller – typically just what the interest itself can support – and grow larger over time as deaths occur and mortality credits are added.

In other words, conceptually a tontine is quite similar in structure to an annuity, in that both pay “mortality credits” – a redistribution of the shares of those who passed away, to support the payments of survivors. The key distinction, however, is that in the case of an annuity the mortality credits are paid from the start (based on the assumption of how deaths will occur in the future, and typically backed by the guarantee of the annuity company), while with a tontine only the baseline interest is paid from the start and the mortality credits are not added on until deaths actually occur (and the dollar amount to redistribute occurs based on those known deaths).

(Notably, another distinction between a tontine and annuity is that usually, the tontine pays only interest plus a rising amount of mortality credits over time, while annuity payments are typically calculated based on a combination of principal as well as interest and mortality credits. The source and significance of this distinction will be discussed further below.)

The History Of Tontines

While the concept of a tontine is new to most advisors and investors of the modern era, it actually has a long and rich history. As documented in his recent book “King William’s Tontine”, retirement researcher Moshe Milevsky finds that the origins of the Tontine date all the way back to the late 1600s. But unlike their annuity cousins – which were primarily designed specifically to provide lifetime income to the annuitant and as a form of “longevity insurance” – the tontine actually originated as a strategy for government borrowing and financing.

While the concept of a tontine is new to most advisors and investors of the modern era, it actually has a long and rich history. As documented in his recent book “King William’s Tontine”, retirement researcher Moshe Milevsky finds that the origins of the Tontine date all the way back to the late 1600s. But unlike their annuity cousins – which were primarily designed specifically to provide lifetime income to the annuitant and as a form of “longevity insurance” – the tontine actually originated as a strategy for government borrowing and financing.

The first documented proposal of a tontine was made by Lorenzo de Tonti (for whom the tontine is named) in 1653, and was proposed as a means for the French king Louis XIV to borrow money to finance his military for its ongoing wars.

In this context, the tontine was actually meant as an alternative to borrowing money through the issuance a bond. Both collect a lump sum from lenders/investors in exchange for ongoing interest or dividend payments, but the hope was that by appealing to the “lottery” nature of the tontine – for at least some investors, there was the potential to get some very big payments if they survived long enough, far beyond those of bond interest alone – that the government might be able to obtain funds at a lower overall interest rate.

In other words, if the government might have to borrow $1,000,000 at 8% for a bond, perhaps the government would be able to borrow at 6% with a tontine, because the investors might be willing to hope/gamble that their share of the 6%-payout-rate from the tontine would eventually exceed the 8% interest rate from the bond. Yet while an individual could receive larger payments over time from the tontine, from the government’s perspective dividend payments would remain at “just” 6% (as the subsequent increases are redistributed from other tontine investors, not from the government making the payments). In addition, since early tontines did not require a repayment of principal either (the payments over time were ultimately meant to provide a recovery of principal and a return on that capital), the effective “borrowing” cost of the tontine was even lower than just the stated interest rate.

While this version of the tontine was not adopted when Tonti first proposed it, several decades later it was implemented, both by King Louis XVI and also King William of England (both done to finance their ongoing French-English war with each other!). With King William’s tontine (after which Milevsky’s book is named), issued in 1693, the payout rate was 7% (plus a 3% bonus to increase the rate to 10% for the first 7 years), while the French issued a tontine in 1689 with a payout rate that varied from 5% to 12.5% based on the age of the tontine nominee upon whose life the payments would be made (which makes sense as those who are older and have a shorter life expectancy should get a higher payout in recognition of the fact that their time horizon is shorter).

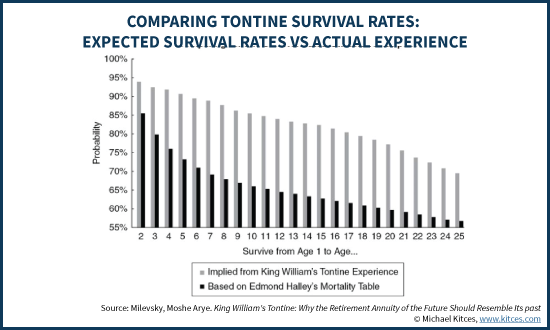

Of course, an obvious risk of the tontine is that the participants may discover a financial incentive to murder fellow tontine annuitants, or take other steps to hasten their demise, given the financial benefit of mortality credits that would accrue. However, in practice the problem with these early tontines was actually the opposite. Some tontines were structured to at least reduce this incentive (e.g., King William’s tontine capped the payments once there were only 7 survivors remaining), but as it turned out, the survival rates of those who participated in tontines was actually far superior to the general survival rates of the population.

In fact, survival rates were so astonishingly good in the earliest tontines that not only does it appear there was a self-selection bias (in favor of healthy participants), and a tendency for investors to take especially good care of their tontine nominees (the “nominee” was the measuring life for tontine payouts), but that there may have been outright fraud as well (e.g., investors choosing a young child as their tontine nominee and if the child unfortunately passed away, picking another child instead and pretending that child was the original tontine nominee).

As a result, ironically within less than a century, tontines had mostly been eliminated as a government financing strategy… because they turned out to be too expensive for the government to keep making tontine payments to so many survivors! In 1770 the French government forcibly converted existing tontines into straight life annuities (eliminating the accrual of any further mortality credits), and during the decade of the French Revolution (beginning in 1789) the tontine payments were further devalued and debased by the French government. The English government issued its own last major tontine in 1789, and their use generally declined from there across Europe (though they still occurred on a smaller local scale for various public and private projects, including a “Tontine-funded Hotel” that still bears the name!).

Tontine Insurance In America And The Origin Of Cash Value Life Insurance

While the use of tontines in Europe as a government financing approach were on the decline by the late 1700s and into the early 1800s, the tontine didn’t even make its first appearance in the U.S. until 1867, where it actually was sold as a form of savings plan for retirement by insurance companies. The first company to issue a tontine was Equitable Life Insurance Company, and the explosive popularity of the tontine built the company into a behemoth. Soon thereafter, other insurance companies joined in, and by the early 1900s a whopping 9 million individuals in the U.S. owned tontine policies, the value of which amounted to an incredible 7.5% of total national wealth at the time (roughly akin to the amount of U.S. national wealth in all IRAs today)!

Since the tontine in the U.S. was used for retirement savings, it was structured differently to accommodate ongoing contributions. According to Milevsky, the policies were typically purchased in small increments over a long period of time (e.g., 20 years) – most commonly using the dividends from participating life insurance policies – and at the end of that time period they would mature and could either be withdrawn as a lump sum, liquidated slowly over time, or used to purchase a single premium immediate annuity (from the same company that had provided the tontine in the first place). However, consistent with the tontine principle, if the investor did not survive the 20-year period, the funds were forfeited (and redistributed to the other policyowners).

Unfortunately, though, the U.S. tontines of the late 1800s not only redistributed the funds to the other policyowners in the event of death during the waiting period. The policies could also lapse – with a total loss to the investor – if he/she was ever delinquent with a single payment along the way (and since the tontines were bundled to the dividend payments from permanent life insurance, this meant the life insurance would have been forfeited too). In other words, the tontine policies would only make their payouts of the cumulative life insurance policy dividends at the end of 20 years if the individual survived, and made every single insurance premium payment on time along the way (and didn’t have any disruptive financial/life event that might cause them to miss a payment). The bad news is that this requirement for “persistency” put extreme pressure on investors/insureds to continue to make timely payments for the insurance/tontine policies. The good news was that with even just a moderate lapse rate, on top of potential deaths, a tontine with a base return of just 4% per year could provide an internal rate of return of more than 10% for those who held on for the entire time period!

Nonetheless, it was this form of loss-through-lapse – and the fact that there were many horror stories of people who lost their tontine investments due to innocent mistakes or even nefarious actions of under-regulated insurance companies – that led to the demise of the tontine in the U.S. In 1904 the New York state legislature convened a special committee to investigate tontine insurance policies, both because of the funds being lost by investors if the tontines were forfeited early, but also because the insurance companies were accumulating huge investment reserves (holding all the tontine investor payments before the end of the 20 year periods) and had almost no oversight or regulation of how the funds must be used (leading to everything from huge commissions for selling tontines, to even bribes to judges and politicians to look the other way and not scrutinize the tontine business).

The end result of the investigation, and subsequent legislation that came from it, forced insurance companies to more thoroughly account for and report on their dividends, and provide a form of “non-forfeiture value” that couldn’t be lost even if the insurance policy were to lapse (which is actually the origin of the “cash value” of permanent life insurance!). The weight of these and other crackdowns on how insurance companies would be required to treat insurance policy owners going forward effectively killed the tontine policy, as within a few years of the new rules no companies (including Equitable) were selling tontines any longer (though the life insurance industry itself actually flourished with the improved public trust brought about by the new regulations).

The Benefits Of A Tontine Agreement Versus An Immediate Annuity

Notwithstanding the disappearance of the tontine from the U.S. retirement picture in the early 1900s, Milevsky makes the case that it’s an idea worth resurrecting for the modern retirement era.

The key distinction, from the perspective of today’s era with pensions and single premium immediate annuities, is that the tontine does not pay mortality credits in advance of (and in anticipation of) the deaths occurring. Instead, mortality credits don’t accrue to the survivors until some members of the tontine pool actually pass away.

The reason this distinction matters is that for an annuity to allocate the payment of mortality credits in advance, based on anticipated life expectancy, there is a risk – the danger that not everyone actually passes away as expected, resulting in a shortfall that can cause the pension or annuity company to default. In other words, the annuity company must not only project expected mortality rates – it must be right, or risk coming up short.

By contrast, with a tontine, where the mortality credits aren’t actually paid until the deaths actually occur, there’s no way a tontine provider can “default” on its promised payments, because the payments themselves are nothing more than distributions of interest (which can be passed through directly from the underlying investments) and re-distributions of mortality credits (which are only passed through as the deaths occur). In other words, in a pure tontine, the “insurance” company acts more as a mere administrator and overseer and conduit for the payments, rather than acting as a provider and guarantor.

Fortunately, in practice annuity companies rarely default. But this is due primarily to the fact that insurance regulation requires insurance companies to hold substantial reserves, specifically to leave a buffer as a margin for (mortality) error. And while this does reduce the danger for annuity owner, it also raises the cost of the annuity itself, as the annuity buyer implicitly pays not only for the annuity itself, but a share of insurance company reserves to hedge against the “risk” of improvements in mortality. Yet if a major medical breakthrough doesn’t actually occur, the excess reserves that aren’t necessary just turn into profits for the insurance company, and don’t inure to the benefit of the annuity policyowner.

From this perspective, the benefit of the tontine is that because there’s no insurance company or other entity backing a mortality “guarantee”, there’s no need for a portion of every annuity purchase to be (implicitly or explicitly) allocated to the insurance company’s reserves. Instead, virtually every dollar placed into a tontine policy can be invested directly for the policyowner, and paid out based on actual earnings and actual mortality credits. Which allows the tontine buyer to get a better dollar-for-dollar return than what the annuity provides for a similar premium contribution.

Of course, the one major caveat of a tontine is that it’s rising-over-time payments do not necessarily align well with the typical retirement spending goal, which at best is for steady (inflation-adjusting) payments over time (as many annuities can and do provide), or even declining payments as discretionary spending falls off in the later years.

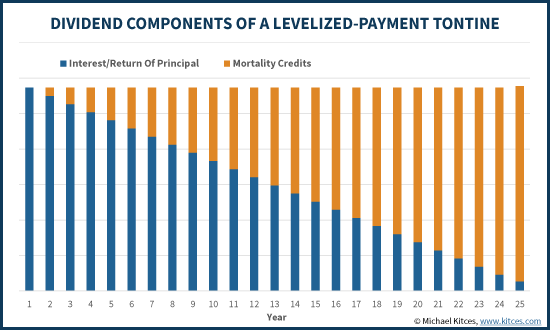

Yet as Milevsky notes, it’s not necessarily a requirement for a tontine to have payments that rise over time. That’s simply the result when the tontine agrees to make level payments of interest (and/or principal) up front, and then stacks mortality credits on top. A tontine could easily be designed with the assumption that the underlying interest payments will start out higher in the early years, and decline over the retirement time horizon (still based on the known cash flows produced by a ladder of bonds), with the idea that as the interest payments decline the mortality credits will increase to offset the decline and maintain a level payment throughout.

The graphic above illustrates a hypothetical tontine payout, where the interest payments are planned (in advance) to be front-loaded and decline over time, but the total payment remains level thanks to the rise of mortality payments as time passes (and tontine participants pass away). In fact, the graphic above is arguably almost identical to the payout from a traditional annuity (which also has declining interest [and principal] over time, supplemented by a growing mortality credit). The difference is that with a tontine, the mortality credits are not guaranteed to follow this path, and could grow slightly faster or slower, depending on actual mortality experience (i.e., the orange portion of the payment in the above graphic could be slightly larger or smaller than projected).

The bad news of this approach to use a tontine in lieu of an annuity is that significant changes in survival rates for the general population (e.g., a major medical breakthrough) could cause the payments to deviate at least slightly (and in theory, significantly) from the original projection (whereas with an annuity they’re locked in, at least as long as the insurance company doesn’t default). The good news, however, is that the payments can potentially be higher in the first place, without the need to have a significant set aside for annuity company reserves (to provide the “mortality credit guarantee”).

Getting Comfortable Again With Tontine Thinking And Are Tontines (Still) Illegal?

Of course, perhaps the most significant challenge of re-introducing the tontine into retirement is simply getting comfortable with the idea of what Milevsky calls “tontine thinking” where payments are determined not based on an insurance company’s estimate of (and guarantee of) mortality credits, but instead the actual mortality of a pool of tontine participants.

In point of fact, Milevsky highlights the reality that there have been novels, movies, and even a Simpsons episode about the tontine concept, all of which includes jokes about – or outright plot twists regarding – the potential for tontine participants to murder one another to more rapidly accrue their mortality credits.

Yet despite these criticisms and fears, the actual history of tontines shows absolutely no evidence that such wrongdoing ever commonly occurred. As noted earlier, if anything the historical data on the earliest tontines suggests that the primary problem was that people consistently lived too long, not too short! In part this was due to the protective design of most tontines – which limited increases in mortality credits once there were only a few participants left (when the incentives for murder would have been greatest). And despite folklore to the contrary, Milevsky shows that even the early 1900s regulations that entirely eliminated tontines from the retirement landscape in the U.S. were driven primarily by the shenanigans of the insurance companies issuing tontines, not the people who were purchasing them.

Notably, there’s also still some debate about whether current law makes tontines outright illegal, or whether the laws of the early 1900s were simply so restrictive insurance carriers chose to stop issuing them (but could start again). And in fact, Milevsky notes that some indirect forms of tontines actually exist in practice today. TIAA-CREF itself, widely known as a major issuer of annuities to teachers, actually offers a form of “participating” annuity (with payouts at least partially adjusted for actual mortality results of the participants), which is at least a cousin to the “pure” tontine structure. And in Israel, it’s common on many kibbutzim for those who live in the kibbutz collective to contribute their funds to a shared tontine pool with their fellow kibbutz participants, who view it as a positive that at least if they pass away, their wealth endows to the survivors of their community. Accordingly, Milevsky points out that one recent effort to blend together the small tontines of many kibbutzim into one many group tontine was actually met with great negativity, because while the larger pool of participants would make tontine payments more stable and predictable (better leveraging the law of large numbers), it would mean the tontine funds of the decedents wouldn’t necessarily go directly to the tontine benefit of their fellow kibbutz members!

At the most basic level, though, arguably a tontine – at least one designed to have level total payments (declining interest payments paired with projected-to-rise mortality credits) – is really nothing more than a form of annuity, where the mortality credits are simply not guaranteed. And of course, the reality is that until we have a medical breakthrough that results in immortality, even without a mortality credit guarantee there’s still a “guarantee” that we will all die someday, and that the mortality credits will eventually be paid. Which means a tontine that “may or may not” be clearly legal under current insurance law is not really very different from a traditional (and completely legal) lifetime annuity that simply allows its annuitants to participate in the changes/improvements in the mortality of the group (or alternatively, a mortality-indexed annuity!).

But in the meantime, Milevsky’s book on “King William’s Tontine” and the history of the tontine agreement makes a compelling case for bringing back tontines, both because the cost structure for the tontine participants can be lower (without the mortality credit guarantee), the group may be comforted by the fact that if they all live longer than expected they will mutually share in the “pain” of a payment decline (which can still only deviate by “so much” given the inevitability of death even with medical breakthroughs), and at least with the simple structure of a tontine the source of every payment will be clear and transparent (which aids in everything from the understanding of the payout structure to the oversight and regulation of tontine companies). All of which are significant positives over the recent woes of the variable annuity industry and their guaranteed withdrawal rider guarantees, not to mention the good old-fashioned traditional lifetime immediate annuity… which, notably, is rarely purchased in today’s environment, unlike the far-more-popular tontines of old!

But in the meantime, Milevsky’s book on “King William’s Tontine” and the history of the tontine agreement makes a compelling case for bringing back tontines, both because the cost structure for the tontine participants can be lower (without the mortality credit guarantee), the group may be comforted by the fact that if they all live longer than expected they will mutually share in the “pain” of a payment decline (which can still only deviate by “so much” given the inevitability of death even with medical breakthroughs), and at least with the simple structure of a tontine the source of every payment will be clear and transparent (which aids in everything from the understanding of the payout structure to the oversight and regulation of tontine companies). All of which are significant positives over the recent woes of the variable annuity industry and their guaranteed withdrawal rider guarantees, not to mention the good old-fashioned traditional lifetime immediate annuity… which, notably, is rarely purchased in today’s environment, unlike the far-more-popular tontines of old!

So what do you think? Would you consider a tontine investment structure for your retiring clients? Would you view the lower cost and greater transparency of a tontine to be worth trading off the ‘certainty’ of an annuity’s mortality credits?