Executive Summary

Every February, the President formulates a budget request for the Federal government, which Congress then considers in coming up with its own budget resolution. And while many provisions of the President’s budget pertain to actual recommendations on appropriations for various government agencies, the proposals often include a wide range of potential tax law changes, recorded in the Treasury Greenbook.

Given that this is an election year and already within less than 12 months of the end of President Obama’s term, there is little likelihood that any of the President’s substantive tax changes will actually come to pass, from a version of the so-called “Buffet Rule” (a “Fair Share Tax” for a minimum 30% tax on ultra-high income individuals), an increase in the maximum capital gains rate to 24.2% (which would total 28% including the 3.8% Medicare surtax on net investment income), or a rewind of the estate tax exemption back to the $3.5M threshold from 2009.

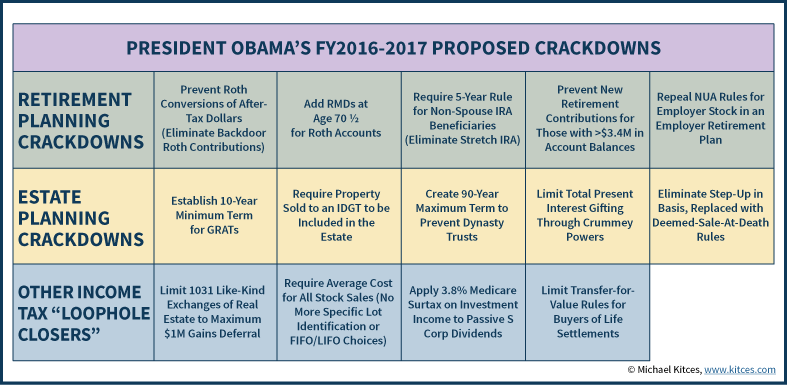

However, the President’s budget proposals do provide an indication of what’s “on the radar screen” inside Washington, including a wide range of potential “crackdowns” and “loophole closers” that could appear in legislation (as was the case with the crackdown on Social Security file-and-suspend and restricted-application claiming strategies last year).

And in this context, it’s notable that the President’s budget proposal does include a wide range of potential crackdowns on individuals, from a new cap on the maximum gain to be deferred in a 1031 like-kind exchange of real estate, to the addition of lifetime Required Minimum Distributions for Roth IRAs after age 70 ½, the elimination of stretch IRAs and step-up in basis at death, shutting down the “backdoor Roth contribution” strategy, and more!

"Loophole Closers" And Other Retirement Planning Crackdowns In The Treasury Greenbook

When it comes to cracking down on retirement accounts, the President’s budget re-proposes a series of new restrictions and limitations, from killing the so-called "backdoor Roth IRA" to the stretch IRA.

When it comes to cracking down on retirement accounts, the President’s budget re-proposes a series of new restrictions and limitations, from killing the so-called "backdoor Roth IRA" to the stretch IRA.

Fortunately, the reality is that all of these crackdowns have appeared in prior proposals, and none have been enacted - which means it's not necessarily certain that any of them will be implemented this year either, especially given that it is both an election year (which tends to slow the pace of tax legislation), and that there won't even be any Tax Extenders legislation this December after last year's permanent fix.

Nonetheless, the proposals provide some indication of what could be on the chopping block, should any legislation happen to be going through Congress that needs a "revenue offset" to cover its cost.

Key provisions that could be changed in the future include:

Elimination Of Back Door Roth IRA Contributions

The back door Roth IRA contribution strategy first became feasible in 2010, when the income limits on Roth conversions were first removed. Previously, those with high income could not make a Roth IRA contribution, nor convert a traditional IRA into a Roth. With the new rules, though, it became possible for high-income individuals ineligible to contribute to a Roth IRA to instead contribution to a non-deductible traditional IRA and complete a Roth conversion of those dollars – effectively achieving the goal of a Roth IRA contribution through the “back door”.

Arguably, completing a backdoor Roth IRA contribution was already at risk of IRS challenge if the contribution and subsequent conversion are done in quick succession, but the proposal in the Treasury Greenbook would crack down further by outright limiting a Roth conversion to only the pre-tax portion of an IRA. Thus, a non-deductible (after-tax) contribution to a traditional IRA would no longer be eligible for a Roth conversion at all (nor any existing after-tax dollars in the account).

Notably, a matching provision would apply to limit conversions of after-tax dollars in a 401(k) or other employer retirement plan as well, limiting the “mega backdoor Roth” contribution strategy that was made possible by IRS Notice 2014-54.

If enacted, the new rule would simply prevent any new Roth conversions of after-tax dollars after the effective date of the new legislation.

Introduce Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) Obligations For Roth IRAs

Under the auspices of “simplifying” the required minimum distribution (RMD) rules for retirement accounts, the President’s budget proposal would “harmonize” the RMD rules between Roth and traditional retirement accounts.

This change would both introduce the onset of RMDs for those with Roth IRAs and Roth employer retirement plans upon reaching age 70 ½ (ostensibly the still-employed exception for less-than-5% owners would still apply to employer retirement plans).

Notably, this “harmonization” rule would also prevent any additional contributions to Roth retirement accounts after reaching age 70 ½ (as is the case for traditional IRAs).

Elimination Of Stretch IRA Rules For Non-Spouse Beneficiaries

First proposed nearly 4 years ago as a revenue offset for highway legislation, and repeated in several Presidential budget proposals since then, the current Treasury Greenbook once again reintroduces the potential for eliminating the stretch IRA.

Technically, the new rule would require that the 5-year rule (where the retirement account must be liquidated by December 31st of the 5th year after death) would become the standard rule for all inherited retirement (including traditional and Roth) accounts. In the case of a retirement account bequeathed to a minor child, the five year rule would not apply until after the child reached the age of majority.

In the case of beneficiaries who are not more than 10 years younger than the original IRA owner, the beneficiary will still be allowed to stretch out required minimum distributions based on the life expectancy of the beneficiary (since the stretch period would not be materially different than the life expectancy of the original IRA owner). A special exception would also allow a life expectancy stretch (regardless of age differences) for a beneficiary who is disabled or chronically ill.

Limit New IRA Contributions For Large Retirement Accounts (Over $3.4M)

First introduced in the President’s FY2014 budget, this year’s Treasury Greenbook also re-proposes a rule that would limit any new contributions to retirement accounts once the total account balance across all retirement accounts reaches $3.4M. As long as the end-of-year account balance is above the threshold, no new contributions would be permitted in the subsequent year (though if the account balance dipped below the threshold, contributions would once again become possible, if otherwise permitted in the first place). All account balances across all types of retirement plans (not just IRAs) would be aggregated to determine if the threshold has been reached each year.

The dollar amount threshold is based on the cost to purchase a lifetime joint-and-survivor immediate annuity at age 62 for the maximum defined benefit pension amount of $210,000 (which means the dollar amount could change due to both inflation-indexing of this threshold, and also any shifts in annuity costs as interest rates and mortality tables change over time).

Notably, the proposed rule would not force existing dollars out of a retirement account once the threshold has been reached. There are no requirements for distribution to get under the threshold, and the rule explicitly acknowledges continued investment gains could propel the account balance further beyond the $3.4M level. The only limitation is that no new contributions would be permitted.

Repeal Of Net Unrealized Appreciation Rules For Employer Stock In An Employer Retirement Plan

In the section of “loophole” closers, the President’s budget proposes (for the second year in a row) to eliminate the so-called “Net Unrealized Appreciation” rules, which allow for employer stock in an employer retirement plan to be distributed in-kind to a taxable account so any of the gains in the stock (the unrealized appreciation) can be sold at capital gains rates.

Characterizing these NUA rules as a “loophole” is ironic, given that the strategy is explicitly permitted under IRC Section 402(e)(4), and has been in existence as an option for employees with holdings in employer stock since the Internal Revenue Code of 1954!

Of course, employee savings habits have changed significantly since the 1950s, as has our understanding of investing and portfolio diversification. The proposed justification for the elimination of NUA is that employer retirement plans now have many other tax preferences, and that at this point the NUA could be an inappropriate incentive for employees to concentrate their investment risks in their employer stock (which further concentrates their risk given that their job is also reliant on the same employer!). The proposal also specifically cites a concern that the NUA benefit may be ‘too’ generous when used with employer stock in an ESOP, which already enjoys other tax preferences.

To ease the transition for those who have already been accumulating employer stock in their retirement plan for many years, the proposal would only apply for those who are younger than age 50 this year (in 2016). Anyone who is already 50-or-older in 2016 would be grandfathered under the existing rules, and retain the right to do an NUA distribution in the future.

Ending GRATs and IDGTs, And Other Estate Planning Crackdowns In The President's FY2017 Budget Proposal

The President’s budget proposal also includes a number of estate-planning-related crackdowns and loophole closers. As with most of the proposals for changes to retirement accounts, these potential “loophole closers” are not new, but do represent the broadest list yet of areas that the IRS and Treasury wish to target.

Elimination Of The Grantor Retained Annuity Trust (GRAT) Strategy

The Grantor Retained Annuity Trust (GRAT) is an estate planning strategy where an individual contributes funds into a trust, in exchange for receiving fixed annuity payments back from the trust for a period of time. Any funds remaining in the trust at the end of the time period flow to the beneficiaries.

To minimize current gift tax consequences, the strategy is often done where the grantor agrees to receive a series of annuity payments that are almost equal to the value of the funds that went into the trust – for instance, contributing $1,000,000 and agreeing to receive in exchange payments of $500,000. To the extent any growth above those payments results in extra funds left over at the end, they pass to the beneficiaries without any further gift tax consequences.

In today’s low interest rate environment, this strategy has become extremely popular, because the methodology to determine the size of the gift is based on calculating the present value of the promised annuity payments. The lower the interest rate, the less the discounting, the more the assumed annuity will return to the original grantor, and the small the gift. In some cases, grantors will simply create a series of “rolling” GRATs that run for just 2 years and start over again, just trying over and over again to see if one of them happens to get good investment performance to transfer a significant amount to the next generation tax-free (as the remainder in the trust).

To crack down on the strategy, the President’s budget proposes that the minimum term on a GRAT would be 10 years (which largely eliminates the relevance of rolling GRATs and introduces far more risk to the equation for the grantor). In addition, the rules would require that any GRAT remainder (the amount to which a gift would apply) must be the greater of 25% of the contribution amount, or $500,000, which both increases the size of the GRAT that would be necessary to engage in the strategy and forces the grantor to use a material portion of his/her lifetime gift tax exemption to even try the strategy.

To further eliminate the value of the strategy, the proposal would also require that in any situation where a grantor does a sale or exchange transaction with a grantor trust, that the value of any property that was exchanged into the trust remains in the estate of the grantor – included in his/her estate at death, and subject to gift tax during his/her life when the trust is terminated and distributions are made to a third party. This would likely kill the appeal of the GRAT strategy altogether, as it would cause the remaining value of a GRAT distributed to beneficiaries at the end of its term to still be subject to gift taxes.

Notably, this crackdown on transfers via a sale to a grantor trust would indirectly also eliminate estate planning strategies that involve an installment sale to an intentionally defective grantor trust (IDGT), as the inclusion of the property exchanged into the trust would prevent the grantor from shifting the appreciation outside of his/her estate.

Eliminate Dynasty Trusts With Maximum 90-Year Term

Historically, common law has prevented the existence of trusts that last “forever”, and most states have a “rule against perpetuities” that limits a trust from extending more than 21 years after the lifetime of the youngest beneficiary alive at the time the trust was created.

However, in recent years, some states have begun to repeal their rules against perpetuities – largely in an effort to attract trust business to their state – and creating the potential of “dynasty” trusts that exist indefinitely for a family, and allow the indefinite avoidance of estate (and generation-skipping) taxes for future generations of the family.

To prevent the further creation of new dynasty trusts, the President’s budget proposal would cause the Generation Skipping Tax exclusion to expire 90 years after the trust was created. As a result, the Generation Skipping Transfer Tax itself could then be applied to subsequent distributions or terminations of the trust, eliminating the ability for subsequent skipping of estate taxes for future generations.

Notably, the proposed rule would only apply to new trusts created after the rule is enacted, and not any existing trusts. However, new contributions to existing trusts would still be subject to the new rules as proposed.

Limit Total Of Present Interest Gifts Through Crummey Powers

IRC Section 2503(b) allows for an annual gift tax exclusion (currently $14,000 per donee in 2016) for gifts that are made every year. However, an important caveat to the rule under IRC Section 2503(b)(1) is that in order to qualify for the exclusion, the gift must be a “present interest” gift to which the beneficiary has an unrestricted right to immediate use.

The present interest gift requirement makes it difficult to use the annual gift tax exclusion for gifts to trusts, as contributing money into a trust that won’t make distributions until the (possibly distant) future means by definition the beneficiary doesn’t have current access to the funds. It’s not a “present interest” gift, and thus cannot enjoy the $14,000 gift tax exclusion.

The classic strategy to work around this rule has been to give the trust beneficiaries an immediate opportunity to withdraw funds as they are first contributed to the trust. The fact that the beneficiary has an immediate withdrawal power ensures that it is a “present interest” gift and eligible for the exclusion. However, the trust is commonly structured to have that beneficiary’s right-to-withdraw lapse after a relatively limited period of time, such that in the short run it’s a present interest gift but in the long run it still accomplishes the goals of the trust. This strategy has been permitted for nearly 50 years, since the famous Crummey Tax Court case first affirmed it was legitimate (such that these present-interest-lapsing powers are often called “Crummey powers”).

However, in recent years a concern has arisen from the IRS is that some trusts had a very large number of Crummey beneficiaries, all of whom would have Crummey powers, such that the donors could gift significant cumulative dollar amounts out of their estate by combining together all the beneficiaries. In some scenarios, there were even concerns that the Crummey beneficiaries had no long-term interest in the trust at all, and were just operating as ‘placeholders’ to leverage gift exclusions. Unfortunately, though, from the IRS’ perspective, the Service has been unable to successfully challenge these in court.

Accordingly, the new proposal would alter the tax code itself to impose limit the total amount of such gifts. The change would be accomplished by actually eliminating the present interest requirement for gifts to qualify for the annual gift tax exclusion, and instead simply allowing a new category of future-interest gifts, but only for a total of $50,000 per year for a donor (regardless of the number of beneficiaries). The new category of gifts would include transfers into trusts, as well as other transfers that have a prohibition on sale, and also transfers of interests in pass-through entities.

Notably, this rule wouldn’t replace the $14,000 annual gift tax exclusion. Instead, it would simply be an additional layer that effectively limits the cumulative number of up-to-$14,000 per-person gifts if they are in one of the new categories (e.g., transfers into trusts). For instance, if four $14,000 gifts were made to four beneficiaries of a trust, for a total of $56,000 of gifts, each $14,000 gift might have individually been permissible, but the last $6,000 would still be a taxable gift (or use a portion of the lifetime gift tax exemption amount) because it exceeds the $50,000 threshold.

It is also notable that since the new category includes “transfers of interests in pass-through entities”, the rule may be used to limit aggressive present-interest gifting of family limited partnership shares across a large number of family members!

Ending Step-Up In Basis And Other Income Tax And Capital Gains Proposed Crackdowns

In addition to the targeted retirement and estate planning crackdowns, it’s notable that the President’s budget proposal includes several additional rules that would impact general income tax strategies, particularly regarding planning for and around capital gains.

Elimination Of Step-Up In Basis, To Be Replaced By A Required-Sale-At-Death Rule

As a part of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001, Congress repealed the estate tax in 2010, and at the same time repealed the existing rules allowing for a step-up in basis, to be replaced with a rule for “carryover cost basis” from the decedent to the beneficiary.

The problem with carryover cost basis rules at death is that they are extremely problematic to administer. Beneficiaries (and/or the executor) don’t necessarily know what the cost basis was in the first place for many investments, or lose track of it, especially if the property isn’t sold until years later. In practice, step-up in basis at death functions as much as a form of administrative expediency for administering the tax code, as an intended “tax break” at death.

Accordingly, the President’s budget proposes a new way to handle the situation: simply tax all capital gains at death, as though the decedent had liquidated all holdings. The capital gains would be reported on the decedent’s final income tax year, and gains could be offset by any capital losses in that year, and/or any capital loss carryforwards. There would an exclusion for the first $100,000 of capital gains (eliminating any capital gains exposure for the mass of Americans with moderate net worth), in addition to a $250,000 exclusion for any residence. Any household furnishings and personal effects would also be excluded from consideration.

Assets bequeathed to a surviving spouse would still retain a carryover in basis, and any unused capital gains exclusion (the $100,000 amount for general property and the $250,000 for a residence) would be portable and carry over (thus making the exclusions $200,000 and $500,000, respectively, for a married couple, due at the second death of the couple). Any transfers to a charity at death would also not be subject to the capital gain trigger.

To avoid lifetime avoidance of the tax through gifting, the proposal would also eliminate carryover cost basis for gifts, and instead require the same capital-gains-upon-transfer rule for a lifetime gift (again with carryover cost basis applying only for gifts to a spouse or charity).

Limit 1031 Like-Kind Exchanges Of Real Estate To A $1,000,000 Annual Limit

Under IRC Section 1031, investors are permitted to exchange a real estate investment for another “like-kind” piece of real estate, while deferring any capital gains on the transaction. For the purpose of these rules, “like kind” is broadly interpreted, even including the swap of unimproved real estate (i.e., raw land) for improved real estate (e.g., an apartment building) or vice versa.

Congress notes that historically, the rules for like-kind exchanges for real estate (and other illiquid property) were allowed primarily because such property could be difficult to value in the first place, such that it was easier to simply permit the exchange and tax the final transaction later, rather than try to set an appropriate value at the time of the transaction (if the investor wasn’t converting the property to cash anyway).

However, given that property is far more easily valued now than it was decades ago when the 1031 exchange rules were originated, the President’s budget proposes to limit the rule to only $1,000,000 of capital gains that can be deferred in a 1031 exchange in any particular year. Any excess gain above that amount in a particular year would be taxable as a capital gain, as though the property had been sold in a taxable event, with the proceeds separately reinvested.

The proposal would also eliminate the 1031 exchange rules for art and collectibles altogether.

Elimination Of Specific Lot Identification For Securities And Requirement To Use Average Cost Basis

Under the tax code, investors that hold multiple shares of property can choose which lots are sold. In the case of dissimilar property like multiple lots of real estate, this rule simply recognizes that only the actual lot being sold should be taxed. However, the case is less clear for portfolio investments, where market-traded securities are fungible and “economically indistinguishable” from each other.

Accordingly, the President’s budget proposes to eliminate the specific lot identification method for “portfolio stock” held by investors, along with any ability to choose a FIFO or LIFO default cost basis methodology, and instead require investors to use average cost basis instead (in the same manner as is done for mutual funds. The rule would only apply to stocks that had been held for more than 12 months, such that they are eligible for long-term capital gains treatment, and would apply to all shares of an identical stock, even if held across multiple accounts or brokerage firms. However, it would only apply to “covered securities” that are subject to cost basis tracking in the first place (generally, any stocks purchased after January 1st of 2011).

Notably, this change was proposed previously in the President’s FY2014 budget as well. Its primary impact would be limiting the ability to “cherry pick” the most favorable share lots to engage in tax-loss harvesting (or 0% capital gains harvesting) from year to year.

Apply The 3.8% Net Investment Income Medicare Surtax To S Corporations

A long-standing concern of the IRS has been the fact that while pass-through partnerships require partners to report all pass-through income as self-employment income (subject to Social Security and Medicare self-employment taxes), the pass-through income from an S corporation is treated as a dividend not subject to employment taxes. Historically this has allowed high-income S corporation owners to split their income between self-employment-taxable “reasonable compensation” and the remaining income that is passed through as a dividend not subject to the 12.4% Social Security and 2.9% Medicare taxes. (Most commonly though, the strategy “just” avoids the 2.9% Medicare taxes, as reasonable compensation typically is high enough to reach the Social Security wage base anyway.)

Since the onset of the new 3.8% Medicare surtax on net investment income in 2013 (along with a new 0.9% Medicare surtax on upper levels of employment income), the stakes for this tax avoidance strategy have become even higher, as upper income individuals (above $200,000 for individuals or $250,000 for married couples) are now avoiding a 3.8% tax (either in the form of 2.9% Medicare taxes plus the 0.9% surtax on employment income, or the 3.8% tax on investment income).

To curtail the strategy, the President’s budget proposal would automatically subject any pass-through income from a trade or business to the 3.8% Medicare surtax, if it is not otherwise subject to employment taxes. This effectively ensures that the income is either reported as employment income (subject to 2.9% + 0.9% = 3.8% taxes), or is taxed at the 3.8% rate for net investment income instead.

In addition, in the case of professional service businesses (which is broadly defined to include businesses in the fields of health, law, engineering, architecture, accounting, actuarial science, performing arts, or consulting, as defined for qualified personal service corporations under the IRC Section 448(d)(2)(A), as well as athletes, investment advisors/managers, brokers, and lobbyists), the rules would also outright require that S corporation owners who materially participate in the business would be required to treat all pass-through income as self-employment income subject to self-employment taxes (including the 0.9% Medicare surtax as applicable).

New Scrutiny Of Life Settlements And Limitations On The Transfer-For-Value Rules

The growth of life settlements transactions in recent years – where a life insurance policyowner sells the policy to a third party, who then keeps the policy ‘as an investment’ until the insured passes away – has brought a growing level of scrutiny to the area.

Under the standard rules for life insurance, IRC Section 101(a)(1) permits a life insurance death benefit to be paid out tax-free to the beneficiary. However, that tax preference is only intended for the original policyowner (who had an insurable interest in the insured), and not necessarily an investor. In fact, IRC Section 101(a)(2) explicitly requires that if a life insurance policy is “transferred for valuable consideration” (i.e., sold) that the death benefits become taxable. Exceptions apply for scenarios where the buyer is the insured (e.g., buying back his/her own policy from a business), or in certain scenarios where the policy is bought by a business or a partner of the business.

From the perspective of the IRS, the primary concern is that some life settlement investors may be evading these rules by forming “business” entities where they can be a partner of the insured (even if the insured just becomes a 0.1% owner), just to buy the policy in a tax-free context.

Accordingly, the President’s budget proposal would modify the transfer-for-value rules by requiring that the insured be (at least) a 20% owner of the business, in order to avoid having minimal partners added just to avoid the standard life settlements tax treatment.

In addition, the new rules would require that, for any insurance policy with a death benefit exceeding $500,000, that details of the life settlements purchase – including the buyer’s and seller’s tax identification numbers, the issuer and policy number, and the purchase price – be reported both to the insurance company that issued the policy, the seller, and the IRS so the Service can track life settlements policies. In addition, upon death of the insured, the insurance company would now be required to issue a reporting form for the buyer’s estimate cost basis and the death benefit payment, along with the buyer’s tax identification number, to the IRS so the Service can ensure (and potentially audit) that the gain was reported appropriately. (For those who actually do report life settlements gains properly, this part of the new rule would have no impact, beyond just confirming what was already reported.)

Silver Linings In The President's FY2017 Budget Proposals

Notwithstanding all the looming "crackdowns", it's important to note that not everything in the Treasury Greenbook is "negative" when it comes to financial planning. There are some silver linings. Favorable provisions include:

- Elimination of Required Minimum Distribution obligations for those with less than $100,000 in retirement accounts upon reaching age 70 1/2

- Marriage penalty relief in the form of a new up-to-$500 two-earner tax credit

- Consolidation of the Lifetime Learning Credit and Student Loan Interest Deduction into a further expanded American Opportunity Tax Credit

- Expansion of the exceptions to the IRA early withdrawal penalty to include living expenses for the long-term unemployed

- Ability to complete an inherited IRA 60-day rollover

- Expansion of automatic enrollment of IRAs and multi-employer small business retirement plans

Of course, as with the proposed loophole closers, these silver lining proposals aren't likely to see implementation in 2016 either. Nonetheless, they form the basis for potential points of change and compromise for tax reform in 2017... which means it's not likely the last time you'll be hearing about these potential changes either!

So what do you think? Which of the proposed changes would be the biggest impact to you and your clients? Do you think some of more appropriate "loophole closers" than others? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

My main motif for Roth conversions in recent years has been to avoid the MDRs of regular IRAs because of the stiff penalties associated with not getting the MDs right. I am shocked that the under the auspices of “simplifying” the required minimum distribution (RMD) rules for retirement accounts, the President’s budget proposal would make my life potentially difficult / subject me to potential penalties again. I also liked the option of being able to leave a chunk of (still tax-free growing) money for my minor daughter(‘s education) should I not need the Roth IRA money for myself.

First, thanks again Michael for a comprehensive write-up on the subject. So informative!

My question relates to backdoor Roth conversion strategy and your statement, “If enacted, the new rule would simply prevent any new Roth conversions of after-tax dollars after the effective date of the new legislation.”

You may not be able to answer this, but I’ll ask anyway. Is it fair to interpret that sentence to say that any Roth conversion done already in 2016 is likely to not be impacted by new legislation or is it possible that the “effective date of the new legislation” could be backdated to January 1, 2016 therefore calling into question any Roth conversion done at any time this year?

Thanks,

Mike

Mike,

It’s certainly POSSIBLE for Congress to backdate the rule. It would be within their purview. But for political expediency, I suspect realistically what you’d see is a near-term future enactment (e.g., this rule will apply for all conversions beginning after 12/31/2016, which is actually the proposed date in the Greenbook).

– Michael

Thanks Michael.

The non-step-up rules proposed for estates are just as unworkable as the 2010 rules. Unless the basis was tracked, no one will know the tax basis for any assets. Also, it will be devastating to any family business.

The real issue is that all the politicians want to use the tax system to right all of society’s ills. Problem of concentrated wealth: Use the tax system to take it from the wealthy. Problem of unaffordable education: Use the tax system to give students money. Problem of unaffordable health care: Use the tax system to subsidize insurance premiums. and on and on. We want to do some of these things, but we need to figure out how to simplify the tax system and accomplish policy goals without using the tax system. There needs to be a simple progressive income tax system, but it has to max out at around 50% all inclusive. There should be a wealth transfer death/gifting tax system, but it also needs to max out (around 30% makes sense to me). That’s it. Get rid of everything else. No deductions, credits, surcharges, AMT, or anything.

Then we have to tackle the corporate tax system!

Michael, your ability to digest so much information and write about it so succinctly always blows me away. You are one of a kind, my friend! May God keep you around and interested in our business for decades to come.

Thanks Burt! 🙂

– Michael

It would be a real nightmare to know the average cost basis for shares in accounts at different broker-dealers. Each BD knows the average cost basis for the shares that it holds, but might not even be aware that shares are being held elsewhere. Trying to create a system to automatically track that information across different BDs would also be a nightmare.

Bruce,

Agreed. Historically the tendency on provisions like this has been to restrict it to “just” the current brokerage firm.

I understand why they would want to go cross-firm on this (otherwise it begs for abuses), but I agree that this seems like a VERY difficult thing to implement in practice. We’ll see?

– Michael

I second Burt’s comments!

Michael, first, I agree with the earlier comment that your ability to digest this information so quickly, and present it in an understandable fashion to us mere mortals, is truly outstanding! One of the provisions I found troubling was the undoing of Notice 2014-54 on NUA. Are taxpayers who are 50 or older grandfathered?

Are you sure this isn’t Bernie’s budget?

Nothing to see here folks. Complete waste of time to read these things just like the last ~5 of them.

These budget proposals are only for show. I mean the least you could do is point out that over half of these have been included in every fake Obama budget proposal and low and behold not a single one has ever been proposed or debated by a single senator or congressmen even in committee.

I realize that few, if any of these proposals will become the law of the land, but still… I don’t like the idea of the rules of the game changing at halftime, or midway through the 4th quarter. I recall the proposal for taxing 529 gains upon withdrawal that was made at last year’s State of the Union address. Of course it gained little traction, but the main reason we use the 529 is for the tax-free withdrawal. The same goes for many of these proposed changes. Simply unfair to those who have been planning based on the rules at the start of the game.

Just helped me to cross lines in becoming a Repudlican

Socialism is alive and well everywhere we look. The people that have done what they should to prepare for their retirement are finding that all that our socialist government has to do to take more of it away from them is to simply change the rules to make a money grab. Voters better pull their head out and vote accordingly!

Amazing to read just how complicated taxes have become and how it then becomes necessary for whole gaggle of professionals (lawyers, accountants, investment advisors) to exist just to tell me WHAT I OWE THE GOVERNMENT WHILE I AM ALIVE AND AFTER I HAVE DIED. Flat tax anyone? Cruz’s plan, as one example, looks mighty good…