Executive Summary

The rule allowing IRA distributions to be rolled over within 60 days to avoid taxation has been around as long as IRAs themselves have existed, whether used simply to facilitate the transfer of an account, to fix a distribution mistake, or for those who want to use their IRA as a form of “temporary loan” to be repaid in a timely manner. However, to prevent abuse, Congress did enact a rule that limits 60-day rollovers to only being done once every 12 months, which the IRS has historically applied on an IRA-by-IRA basis.

In the recent case of Bobrow v. Commissioner, though, the Tax Court expanded the interpretation of the once-per-year rollover rule, changing it from applying one account at a time to instead being applied on an aggregated basis across all IRAs, effectively killing a popular form of sequential-rollovers-as-extended-personal-loan strategy.

The IRS has declared that it will begin to enforce the new aggregation-based IRA rollover rules in 2015, with a special transition rule that will still allow old 2014 rollovers to cause a 1-year waiting period for just the accounts that were involved and not all IRAs. Nonetheless, going forward advisors and their clients will need to be more cautious than ever not to run afoul of the rules when engaging in multiple 60-day rollovers over time… or better yet, simply ensure that IRA funds are only moved as a trustee-to-trustee transfer to avoid the rules altogether!

The Original Once-Per-Year 60-Day IRA Rollover Rule

When funds are withdrawn from an IRA to be spent, they become taxable as ordinary income (with a possible early withdrawal penalty to apply as well). However, in some cases – especially in the early days of IRAs – the account owner might take a withdrawal from the IRA, not with an intent to spend the money, but simply because the owner was in the process of transferring the account to another financial institution. Alternatively, in other cases, the funds were withdrawn as a mistake (e.g., the ‘wrong’ account was liquidated where the account owner had an IRA and another bank or investment account).

To facilitate correcting such mistakes, and allowing for transfers between institutions, Congress included IRC Section 408(d)(3), which allows for an IRA distribution to be treated as a “rollover” that is contributed to a new account. Under the relatively straightforward rules, any distribution taken from an IRA would not be treated as taxable, as long as the funds were re-contributed to (the same or) another IRA within 60 days of receipt. Technically, it didn’t matter whether the purpose of the distribution was to facilitate a transfer, because it was taken as a mistake, or simply out of a desire to use the funds as a personal short-term loan; as long as the rollover contribution was made within 60 days, the distribution would not be taxed.

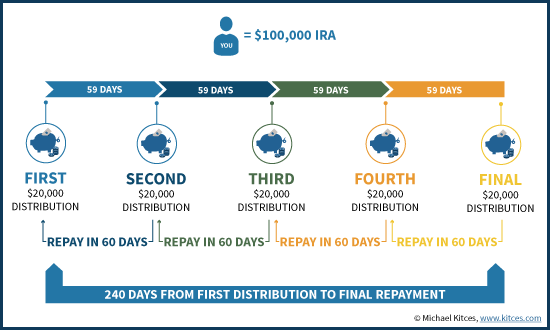

However, the caveat to this rollover rule is that it created the potential for abuse. An individual with a larger IRA could potentially chain together a series of smaller rollovers, allowing for an extended period of personal loans far beyond the 60-day period. For instance, an individual with a $100,000 IRA could take a $20,000 distribution, and then 59 days later take a second $20,000 distribution to repay first, and then another 59 days later take a third $20,000 distribution to repay the second, etc., ultimately stretching out a $20,000 60-day rollover into series that spans more than 9 months before the final $20,000 replacement must be made.

To prevent this kind of potential abuse, Congress also created a limitation to rollovers under IRC Section 408(d)(3)(B), which stipulates that the special rollover treatment from an IRA only applies once in a 1-year period; in other words, if an IRA distribution is received, it cannot be rolled over if there was another distribution received (that was also rolled over) within the past 365 days. Or viewed another way, once a distribution is received (with a plan to roll it over), no subsequent distribution that is received within 365 days of when the original distribution was received will be eligible for a rollover. In the earlier example, this would prevent the strategy because once the first $20,000 distribution was replaced as a rollover, the second $20,000 distribution wouldn’t be eligible for 60-day rollover treatment until 365 days had passed from the first distribution (and likewise for the third and subsequent distributions as well).

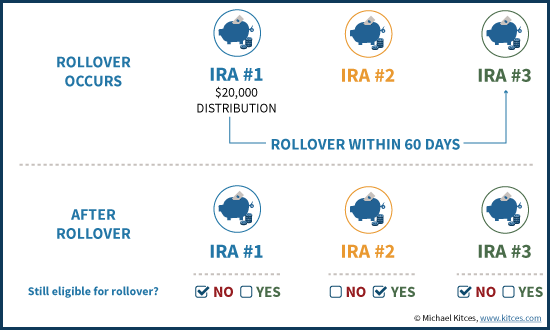

Notably – in part to ease administration and oversight – the IRS interpreted this once-per-year rollover rule to apply on an IRA-by-IRA basis. Thus, as explained in Publication 590, if an individual had IRA #1 and IRA #2, and took a distribution from IRA #1 and did a 60-day rollover to new IRA #3, then for the next 12 months there could be no new IRA rollovers from accounts #1 or #3. However, any distributions from IRA #2 would remain eligible for a rollover, since that particular IRA had not been involved in a rollover (yet).

In addition, under long-standing Revenue Ruling 78-406, a transfer that is handled as a direct trustee-to-trustee transfer (from one IRA custodian to the other, without ever having the funds paid out directly to the IRA owner themselves) does not actually count as a “rollover”, and thus does not have the 60-day requirement nor trigger the start of a 1-year period for preventing subsequent rollovers.

Bobrow v. Commissioner And The Use Of Sequential Separate IRA Rollovers As An Extended Loan

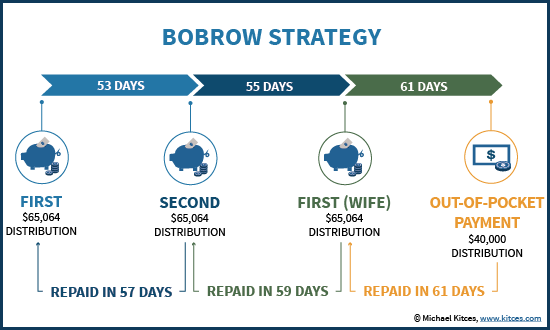

In the recent case of Bobrow v. Commissioner (TC Memo 2014-21), the taxpayer Bobrow did in fact engage in a series of sequential rollovers from separate IRAs to try to facilitate a form of the extended loan strategy. Using a combination of two of his own IRAs, and one from his wife, Bobrow first took $65,064 from his IRA #1, then took $65,064 from his IRA #2 and used it to repay IRA #1, and then took $65,064 from his wife’s IRA to repay his IRA #2, with the ultimate plan of finally replacing the $65,064 in his wife’s IRA later.

This kind of sequential loan strategy was indirectly based on the IRS’s view that the 60-day rollover period applies separate for each IRA under the aforementioned guidance in Publication 590. However, in the process of executing the strategy, Bobrow made a mistake – the final rollover to his wife’s IRA accidentally occurred after 61 days, violating the 60-day rollover rule. In addition, the final rollover contribution to the wife’s account was only $40,000, and not the full $65,064. (Bobrow claimed that he had made a timely request to complete the last rollover and that he had requested the full $65,064 and therefore should have been in the clear, but couldn’t produce any evidence to substantiate this.) Given that the last rollover was not complete, it was reported as being partially taxable, but Bobrow disputed it, which is what ultimately drew the IRS’ attention.

In Tax Court, the IRS did acknowledge the separate IRA rule, but nonetheless maintained that since IRA #2 was involved on both sides of a rollover (as the distribution from #2 was repaying #1, and a later distribution was then also used to repay #2), it should be ignored as an intermediary step, and that under the step transaction doctrine the whole arrangement should be treated as a single IRA rollover that started when the money came out of IRA #1 and ended when the money was repaid into IRA #2 (which would mean it violated the 60-day rule).

In the end, the Tax Court not only supported the IRS’ decision, it went even further, and declared that since under IRC Section 408(d)(2) that IRAs are aggregated together for income tax purposes, that the aggregation should apply for the once-per-year rollover rule as well. In other words, in the Tax Court’s view, once a distribution is taken from any IRA that an individual owns (and is subsequently rolled over), the 12-month blackout period for 60-day rollovers will apply for all of that individual’s IRAs! In other words, the once-per-year rollover rule would apply across all the IRAs, even if different IRAs were involved in each rollover transaction. Notably, this meant the Tax Court even overrode the IRS’s own Publication 590, as in the Tax Court’s view, once a 60-day rollover occurs from IRA #1 to IRA #3, then no 60-day rollover can occur from any IRA for another 12 months, including the previously untouched IRA #2!

The New 60-Day IRA Rollover Rules And The 2015 Transition Rule

Shortly after the Bobrow decision, the IRS issued Announcement 2014-15, in which it declared that it would acquiesce to the Tax Court regarding the rollover rule and begin applying it on an aggregated basis across all IRAs (and change the wording in Publication 590 accordingly). However, to allow time for it to update its rules, and as a form of amnesty for those who were previously relying on its “old” guidance, the Service declared that it would not begin to enforce the rules until 2015 (so those who were in the midst of rollovers already would have until the end of the year to wrap them up).

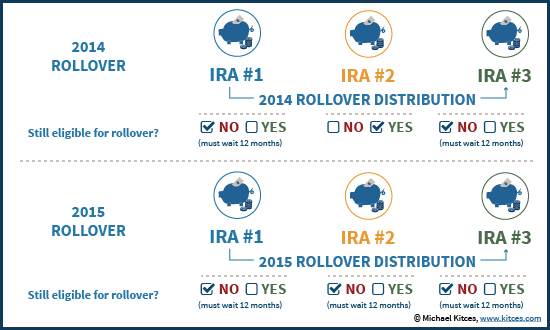

In its recent subsequent IRS Announcement 2014-32, the Service has further clarified how it will apply the rules going forward, including most notably the transition from the old rules (separate IRA treatment) in 2014 into the new rules (aggregated IRA treatment) in 2015. Under the transition rules:

- A distribution that occurs on/after January 1st of 2015 and is rolled over will trigger the 1-year waiting period for all IRAs. (This is a standard application of the new rules.)

- A distribution that occurred in 2014 will continue to only trigger the 1-year waiting period for the IRAs actually involved in the rollover, and will not trigger a waiting period for any/all other IRAs on an aggregated basis.

These transition rules will effectively apply for just 2015, as by 2016 any/all prior IRA rollovers will have occurred since January 1st 2015, and thus all IRA rollovers will be subject to the new (aggregated) rules for determining the 1-year waiting period.

In Announcement 2014-32, the IRS also clarified the treatment of certain other types of rollovers and transfers that do not trigger the 1-year waiting period for any other 60-day rollover, and are not restricted to being done if already within a blackout period due to another rollover:

- Conversion from a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA

- Trustee-to-trustee transfer (under the existing Revenue Ruling 78-408)

- Rollover to or from a qualified plan (e.g., rolling over from a 401(k) to an IRA, or from an IRA back to a 401(k))

On the other hand, the IRS did point out that while a Roth conversion doesn’t trigger the rules, the aggregation rule does draw together both traditional IRAs and Roth IRAs for their own 60-day rollovers. Thus, for instance, if an individual did a 60-day rollover from one Roth IRA to another Roth IRA, that would trigger the 1-year waiting period for another 60-day rollover from any other Roth or traditional IRA from that same individual (and vice versa that a 60-day rollover from a traditional IRA would trigger the blackout period for a Roth-to-Roth 60-day as well).

Beyond the transition rules, though, the simple reality is that under the new once-per-year 60-day rollover rules, the kind of sequential-rollover “extended loan” strategy that Bobrow (and others) have engaged in over the years is now dead. Although a single 60-day rollover could still theoretically be used as a temporary short-term loan (but be very cautious to complete it in the requisite 60-day time window!), chaining together multiple rollovers is just no longer feasible. And in fact, those who otherwise do 60-day rollovers from time to time – for any reason – need to be cautious in recognizing that such a rollover from any one IRA can trigger the waiting period and invalidate a subsequent rollover from any other IRA within a year!

Of course, the reality is that most IRA transfers are already done as a trustee-to-trustee transfer, which both avoids the risk of violating the 1-year waiting period, and does not trigger the start of a new one either. And for most who simply want to transfer IRA funds, the trustee-to-trustee transfer remains the best path. But for those who want and need to do a 60-day rollover for other purposes – e.g., where just transferring the money isn’t enough, or isn’t the sole goal, because the IRA owner actually wants to take possession of the funds and “use” them for a period of time – it will become more important than ever to monitor when other IRA rollovers have been done, as the 12-month waiting period is now broader than ever!

Thanks for the article, Michael. For some reason, in scanning the various headlines on this new rule, I never picked up that this is not an issue with trustee-to-trustee transfers or 401(k) rollovers.

I can’t recall ever having a need to do a 60-day rollover, so thankfully this is a non-issue for my clients!

-Elliott

Finally a piece that does a great job of explaining this! Thank you!

Happy to be of service! 🙂

I’m aware of the Bobrow v. Commissioner case and the 1 yr. wait period between all clients’ IRAs,

yet is it 1 yr from date of distribution or 1 yr from date of repayment or rollover please?

1) Client distributed funds from IRA Jan 2, 2015 to use as RE bridge loan.

2) Client repaid exact sum distributed back into his IRA 59 days later, on 3/2/2015.

Can client take a new 60-day IRA Int free distribution after Jan 2nd, 2016, or after March 2, 2016, and not violate the new law please?

Thanks so much!

Debra,

The 1-year blackout period for rollovers is measured back to the date of the original distribution.

So if the client took the first distribution on January 2nd of 2015, the next 60-day rollover can happen for a distribution on January 3rd of 2016 (or later). When the January 2nd 2015 distribution was actually rolled over is irrelevant (presuming it was successfully rolled over at all). The distribution dates (or technically, the dates the distributions are RECEIVED) are what trigger the measuring period.

– Michael

What if, within the 60-day limit, Mr. Bobrow had repaid his original loan from his IRA with a loan from his wife’s IRA, and then repaid that loan, also within its 60-day limit. Would the Bobrows have successfully borrowed the loan amount for 120 days without penalty?

So we have been dealing with a company takeover then funds were issued for direct rollover…after several attempts to have the recieving company take the funds ie..incomplete forms, missi g info, things getting sent back…1 check missing…we are now being reissued for the second time a check to rollover only at this pont so much time has passed…should we worry or does the 60day period restart? We have never cashed or deposited funds…we are in a mess of miscommunication and missinformation and scared to death

I have made the mistake of taking two separate withdrawals paying them both back unaware of this new ruling. If I am liable for the taxes on the second one then his do I withdraw the funds again without an additional flag being raised?

Bob

I have been told by a tax accountant that if I take a 60 day rollover the tax must be paid immediately, and will not be returned until the following year’s refund is received from the IRS. Can this be correct?

If you take a direct distribution FROM AN EMPLOYER RETIREMENT PLAN, the employer may withhold 20% for taxes, which requires you to make up that amount out of pocket as part of your rollover and then receive it back as a refund later.

However, this does NOT apply if you do a direct trustee-to-trustee transfer from the employer retirement plan to the IRA. And it does NOT apply to an IRA-to-IRA rollover, ONLY to a distribution from an employer retirement plan (e.g., a 401(k)).

– Michael

Thank you. My self directed IRA rollover should be without a tax event.

If I take money out and do a 60-day transfer, am I allowed to pay that money back in installments? Or does all of the money have to go back into the original account at the same time?

If I withdraw 100,000 from brokerage Ira and the send the endorsed check to one insurance company withloi to open 2 annuity accounts of 50,000 each, have I violated the one 60 day per 365 days because I put the rolled over funds into more than one new Ira; or does a a violation occur if and only if I do a second Ira withdrawal within 365 days of first? In short does the number of iras set up at the receiving company have any bearing on whether a violation has occurred.

If I take a 401K distribution on Nov 3, 2016 and the 60 day period expires on January 2, 2017, does the distribution apply to my 2016 tax return or to the 2017 tax return?

It was a 2016 distribution, it applies on your 2016 tax return.

– Michael

Hello. On the off chance that anybody see this (!), per the above scenario of taking the distribution on Nov 3rd (and it applying to the 2016 tax return)…how would I show in my 2016 taxes that the distribution was rolled back in on Jan. 3rd 2017? I would not have 1099R until the next tax year and would only have a confirmation from the fund company that the rollover happened within 60 days.

Michael, Thank you for the informative blog. a few questions: I read that the a 401(K) plan to IRA rollover, be it direct or indirect, not trigger or count against the 1-year limitation. is this correct?

Below is the scenario i am facing:

1) Dec 2015 – 401(K) to IRA#1 Direct Rollover (Check was mailed to me but it was addressed to IRA bank with my name as FBO. No tax withheld as Employer considers this direct rollover (i.e. i can’t cash the check) 1099-R: Box 2 = 0, Box 7 = G

2) May 2016 – IRA#2 to IRA#1 Indirect rollover. Received check from IRA#2 in my name and deposited check “as is” in IRA#1. No tax withheld as per my direction.

Question: Can i repeat the 401(k) rollover just as in 1) above in Sep 2016? my employer allows me to rollover matching funds but want to be careful not to trigger any tax issues

Michael,

Here’s a scenario I can’t find an answer for easily. An IRA owner set up monthly payments out of her IRA. She took two of those payments out of her IRA ($5,000 each) on July 2 and August 2. Then she rolled the $10,000 back into the IRA on August 10. Monthly payments were then discontinued.

I’m assuming since there was only one redeposit that it was one rollover. But am I wrong?

David

So I take this to mean that I can withdraw traditional IRA funds to pay a medical bill and, as long as I can repay/redeposit the amount within 60 days, and I only do it once every 365 days, it will be tax free?

Can I withdraw a portion of money from an IRA within an annuity ,use it for a real estate purchase, then pay it back to a different IRA within 60 days, , from a different real estate transaction? Burning question?. I was already told AIG, doesn’t have that plan, but can I roll it over to another retirement ira that I have with Waddell and reed?

So I take this to mean that I can avoid tax when I withdraw traditional

IRA funds to pay a medical bill (for example), as long as I can

repay/rollover amount within 60 days and I only do it once every 365

days?

Also should I tell the institution anything at the time I

take the initial withdrawel about how I’m planning to pay it back? Or

will they automatically understand and categorize it correctly when the

funds are repaid/rolled over within 60 days?

The once-per-year rule only applies to the same money7. If you have two 401(k)s, you can roll both over in the same year. Generally, do a trustee-to-trustee, because it’s safer.

I have 3 separate IRA’s. Being unaware of the new one rollover rule, I contacted the separate trustees of my IRA1 and IRA2 on the same date and requested that they wire transfer the funds to my personal account. Once I received those funds, I wrote one check for the full amount of both IRA’s and deposited it into one new IRA well before the 60 day period expired. Since both distributions were received and the total amount of both were deposited to one account within the same 60 day period, will this qualify as one rollover within the 12 month period?

(additional info) – the wire transfer deposits from my IRA1 and IRA2 do show up on my personal account on different dates due to processing time. One shows 9/27/16 and the other 9/29/16.

I am still looking for an answer to the following. I took a withdrawal on 11/20/16 and plan on taking an additional withdrawal on 12/20/16. If I put the full amount of both withdrawals back in the IRA with the 60 days of the first withdrawal (1/19/2017), will I avoid tax and penalties on both withdrawals?

Ed,

This doesn’t appear to be permissible under the new rules.

The fact that the 11/20 distribution is rolled over, means the subsequent 12/20 distribution would be ineligible for rollover. The rules are specifically written to prevent two different distributions being rolled over in a 12-month period (even if you try to roll over both at the same time). It may be hard to catch if you roll over both at the same time, but it would be a violation of the once-per-12-month rollover rules.

– Michael

Thanks Michael. My gut told me that was the case.

Michael – Great blog. Thanks. Can you confirm if this is per SSN? If my wife and I have independent IRA’s could we repay one IRA with a rollover from the other?

Question: I did a 60 day, $50,000 indirect rollover, classified as a premature distribution from Trowe on Dec 1st. This made the full repayment to a new retirement account due Feb 1st. On Jan 20th, I deposited $40,000 into the new retirement account. On Jan 30th, I deposited the remaining $10,000 into the same retirement account. To confirm, though paid on two dates, all $50,000 was indirectly rolled over from Trowe to the new retirement account within the 60 days. Now the new requirement account is balking at the 2nd payment, saying it can’t be done as two payments, even though within 60 days.

I did this before, no issue. Any suggestions on how to handle? Or documentation to provide to the new retirement account?

thanks,

John

My bank mistakenly transferred monies to another IRA without my knowing it. When I found out I called The Insurance Company where the monies were sent and was told they would reverse my monies back to the bank – however at that point I got one of those releases saying I release them of any consequences. I would like the monies to be returned to the Bank and then transfer those monies to a different account What will be the result??? Total is $27K – Can I have them send to the Bank and then transfer that money into an IRA I already have and can add to..

I plan to use the proceeds from deregistering my previous employer’s 401(k) to fund a bridge loan for a new home purchase with my spouse, with the intention of subsequently depositing 100% of the deregistered funds into an IRA within 60 days. Does anyone here know what would happen in the event that I were to die during those 60 days? Although it’s an unlikely scenario, I want to ensure that my estate (and my spouse) is not saddled with a few hundred thousand dollars of extra income for that tax year should this occur. Can I pre-authorize the deposit into my existing IRA with a signed form that my spouse could use to deposit the funds if necessary? Are there any other strategies that might address this risk?

Thanks!

Great blog! Quick question…

I withdrew $5000 from my IRA (it’s a personal IRA, not through an employer) on May 1st. Paid $1000 on May 15th and I want to pay the balance of $4000 on June 15th, which is well within the 60-day period. It seems I can’t make payments back to my own account and have to wait until the completion of 365 days because of IRS?

I read about the 60-day rule, it talks about not withdraw funds within 365 days but doesn’t talk about repaying multiple times…. any thoughts??

Does IRS care where the proceeds come (ex. a loan ) from to meet the 60 day rule to repaid the withdrawal?

If I take 100K from my IRA to use as a RE bridge loan (IRA with Fidelity, and they have withheld 10%) Can i borrow 100K from another financial institution and repay my IRA within 60 days to avoid paying ordinary income tax on the initial $100K distribution?

1) So what happens if one screws up and does a second 60-day rollover before the 1-year waiting period is up? Which one doesn’t count? Are there other penalties associated with that scenario?

2) Are 60-day rollovers in a spouse’s IRA completely independent of those in one’s own? i.e. Do they each have their own separate 60 days to repay and their own separate 1-year waiting period before doing another?

Thanks.

Micheael,

Does the 60 day pay back period also apply to the self directed IRA. For example, i had a debt due, borrowed the money from IRA, now have a loan in place to pay the debt, and want to repay the IRA. Can I without difficulty if it is a self directed IRA?

Michael,

Thank you for the information above. It cleared up a lot as did some of questions below. I have a question also: My husband took a $5000 distribution from his IRA on 2/10/17 and then a $24,000 distribution on 2/23/17. He paid the entire amount of $29,000 back on April 6, 2017, which was before the 60 day rollover limit starting with the first distribution on 2/10/17. Is it ok that he took 2 distributions as long as the entire amount was paid back before the first 60-day rollover limit?

I wish to take some money out of my Roth IRA but plan on returning it prior to 60 days. I assume it is ok to do so since it will be from my account and not his? Thank you.

Am I allowed to take additional funds from my IRA during a 60 day rollover period? E.g. I take $10000 out of my IRA on November 1 intending to put it back on December 15. Am I allowed to take an additional $5000 out on December 1st without affecting the rollover of the original $10000? I plan to pay taxes on this $5000.

We are using the 60-day rollover to make it simpler for us to come up with a down payment on a new home purchase. I took a withdrawal in early December 2017 and plan to repay the money in late January 2018 (the mortgage closes in Dec). Is there any problem with this because it involves two different tax years?