Executive Summary

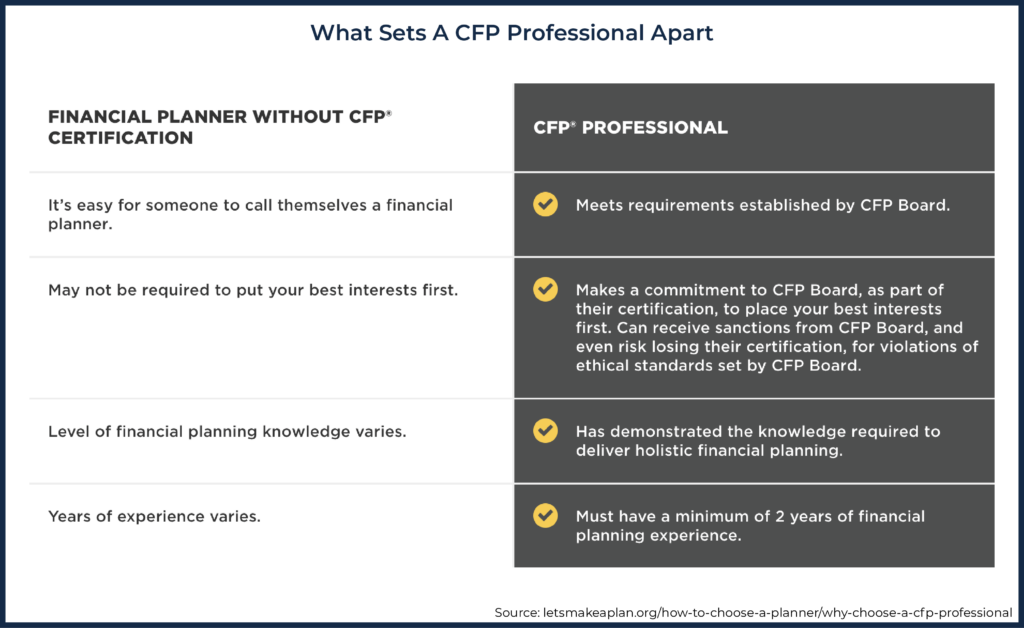

One of the most important aspects of the development of financial planning as a profession is the setting of standards, both for the practice of financial planning and for those who can call themselves a Certified Financial Planner (CFP) professional. But while CFP Board has created a universal set of practice standards, the experience requirement for CFP certification can be fulfilled in a variety of ways and does not require experience working directly with clients.

The range of accepted options available to fulfill the experience requirement leads to newly minted CFP professionals with varying skill levels to handle the client issues they will face as a financial planner. Which means that clients may not get a consistent level of quality and service from financial advisors, even though they may be CFP practitioners. However, by replacing the current options of broadly defined experience requirements with a comprehensive universal training program for all aspiring CFP certificants, the profession could potentially elevate what it means to have CFP certification, in addition to ensuring that clients of CFP professionals can be confident that they will receive consistent, high-quality financial planning consumer experiences.

Such a comprehensive universal training program could be modeled on the accredited experience requirements that prospective doctors must complete to achieve certification. Following medical school – which provides a mixture of didactic lectures, interactive training opportunities, and heavily supervised patient experiences – graduates generally engage in a 1-year internship and a 2- to 6-year residency program where they are given increasingly more responsibility under the supervision of higher-level residents and attending physicians. This model of accreditation emphasizes the resident reaching significant experience ‘milestones’ instead of just the amount of ‘time served’. The resident’s progress is tracked by monitoring education and achievements using real-time data.

A financial planning residency program that replicates this format, where an expansive body of knowledge is reinforced through relatively standardized educational experiences, would help to create a consistent curriculum providing CFP professionals with the right breadth and depth of training to prepare them for a wide range of client encounters. Over the course of 3 years, aspiring CFP professionals (who have already completed the education requirements for CFP certification) can gain the experience needed across the range of financial planning practice areas to become a successful CFP professional. At the same time, throughout the 3-year program, residents are immersed in aspects of practice management, including compliance, business planning, and understanding the firm’s financial status. In addition to assuring clients that the CFP professional they are working with has both the education and expertise to serve their needs, such a training program would also give new advisors the confidence that they have been prepared to handle client issues they will face in their work as a planner.

Ultimately, the key point is that by using the medical field as a guide to create standardized and valuable residency programs for financial advisors, the financial planning profession can develop an educational structure that will not only raise the image of the profession among consumers, but also provide new financial planners with the real-life experience they need to build confidence and serve clients on their own!

The financial planning profession has matured tremendously since its conception roughly 50 years ago. Today, the primary credentialing organization of the profession, now known as the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards, Inc. (CFP Board), oversees more than 90,000 currently active CFP professionals in the United States and its territories operating under a universal set of practice standards.

The CFP Board, with the help of professional organizations like the Financial Planning Association (FPA) and the National Association of Personal Financial Advisors (NAPFA), as well as hundreds of educational institutions, work to arm financial planners with tools, education and communities that will maximize their ability to serve consumers effectively. These organizations have elevated the profession by bringing planning professionals together to share knowledge and practices over the last several decades.

As the profession has matured, these professional and educational institutions have grown to share increasingly similar information about how best to practice financial planning. The CFP Board now provides very clear expectations for practicing CFP professionals. Yet, the experience component required to ‘enter’ the profession under the CFP Board has not yet been standardized to ensure that professionals have the skills necessary to meet those expectations. As a consequence, the experience a consumer can have with a newly minted CFP professional can vary significantly, as can the professional’s capacity to actually adhere to the standards and processes set forth by the CFP Board itself.

New CFP Professionals Must Often Rely On Luck To Gain The Experience Needed To Become Successful Advisors

While the CFP Board provides lucid direction for the education, examination, and ethics components of attaining its preeminent financial planning credential, best practices for the experience requirement component remain ambiguous and explicitly do not require comprehensive planning experience before obtaining the mark! This poses a challenge in the CFP Board’s quest to produce excellent, holistically focused financial planners.

As financial advisors, our profession is not the first to face a uniform-training challenge. Other vocations, like the medical field, have conquered this struggle in the past by creating formalized programs that include a universal training experience requirement before awarding professional independence in the field. Medical residency programs provide a bridge upon which medical school graduates can apply the technical knowledge they’ve learned with real patients under the supervision and guidance of practicing doctors.

Beyond the curriculum for CFP certification, initial opportunities for new advisors to gain the skills needed to succeed in the field largely come down to luck. This suggests that the next step in our journey as a profession is to explore how we, too, can universalize the training experience of up-and-coming advisors to mirror that of deeply established professions like medicine.

By directing a standardized financial planning residency program, CFP Board can help us achieve a common standard of excellence, boosting trust in the CFP mark itself and the profession at large.

How Candidates For CFP Certification Can Fulfill Their Experience Requirement

The CFP Board’s required education curriculum and examination introduce advisors to a swath of important information; however, the absence of a formalized and universal experience curriculum leaves it up to firms and aspiring advisors to create their own plan for learning how to effectively apply that knowledge with clients in the real world.

The four key components of the CFP Board’s certification process – education, examination, experience and ethics – are essential to the cultivation of competent advisors. However, without deeper instruction, oversight, and uniformity across the experience process itself, there is no measurably consistent standard of skill and competence that lies at the end of the credentialing process.

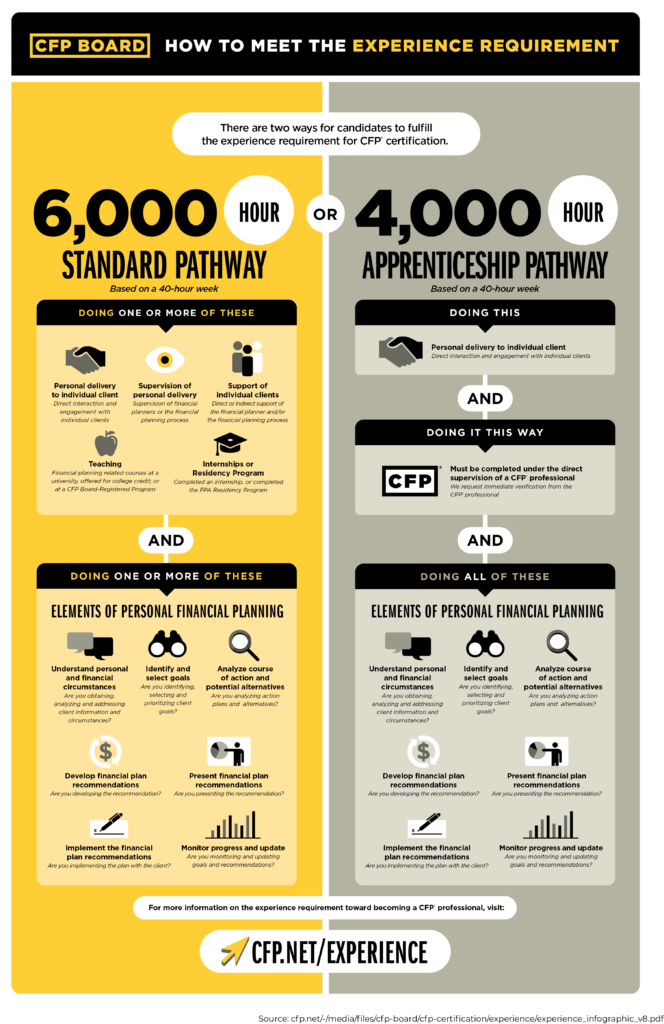

The experience component, as it exists now, is fairly loose. There are two pathways by which candidates can satisfy the experience requirement: the “Standard” 6,000-hour pathway and the 4,000-hour “Apprenticeship” pathway.

The 6,000-hour Standard pathway requires that a candidate’s experience fall in at least one of the following seven primary areas of financial planning:

- Understanding the client’s personal and financial circumstances;

- Identifying and selecting goals;

- Analyzing the client’s current course of action and potential alternative course(s) of action;

- Developing the financial planning recommendation(s);

- Presenting the financial planning recommendations(s);

- Implementing the financial planning recommendation(s); and/or

- Monitoring progress and updating goals and recommendations.

The above experience requirement can be satisfied through the following five ways:

- Personally engaging with individual clients;

- Supporting the financial planner and/or financial planning process (directly or indirectly);

- Supervising financial planners and/or the financial planning process (which may also involve direct client interaction);

- Completing an internship or the Financial Planning Association (FPA) residency program; and/or

- Teaching college-level courses in financial planning concepts.

These very general guidelines render the experience requirement for candidates largely meaningless as an indicator of actual experience to consumers of the mark, simply because almost anything in financial services will be counted toward the requirement, despite the Board’s call to CFP professionals to use their experience and education in adopting a holistic, personalized approach to planning. As it stands, the CFP Board allows candidates to meet the experience requirement under the Standard pathway by providing “indirect support”, such as employee benefits administration, alone for 6,000 hours. Can you imagine if doctors were deemed to have met their experience requirement to service patients because they had three years of experience working in the administration and billing department of the hospital?

The 4,000-hour Apprentice pathway improves on the Standard pathway in that it requires experience in all seven primary areas of financial planning. In addition, all 4,000 hours must be delivered by personally engaging with individual clients and all 4,000 hours must be completed under the direct supervision of a CFP professional, which is ultimately verified by the CFP Board with that CFP professional. This second pathway’s set of requirements is much more supportive of the Board’s assurances of what the mark indicates about the professional.

Even so, the 4,000-hour pathway does not provide a roadmap for progressing or measuring skill acquisition in each of the eight core planning areas from the education requirement component or the seven steps of the overall financial planning process. The ambiguousness of the criteria allows the overseeing CFP professional to be subjectively lenient in their assessments of a candidate’s experience because there is no formal guidepost against which they can measure the candidate’s training experience.

How Advisors Currently Obtain Experience

Budding advisors are left to depend on the education encouraged and provided by the institutions for which they work… which can vary a great deal depending on factors like work culture and revenue-generation sources for each firm.

Furthermore, without a detailed roadmap to proficiency, it is difficult for new planners to assess their own readiness to handle client situations. And the same is true for the mentors training those new advisors, as mentors often use benchmarks based on their own personal performance metrics, or rely on the existing standards of the institution for which they work, to assess the readiness of new planners to be turned out to the consumer population.

Naturally, these standards of excellence and scope can vary widely from firm to firm. In practice, firms will diverge in how they triage attention to the core planning areas depending on their revenue model, internal structure, and the current needs of the firm. And with no apparent incentive to design universal training and progress measures, why would firms be motivated to rise to the challenge to do so – especially if what they’re already doing is enough to satisfy the requirements for the CFP mark, which will (hopefully!) continue to enhance consumer trust in the firm and the advisor later on?

Minimal training requirements from the CFP Board leave firms free to place budding advisors in positions and programs most beneficial to the organization first, making the long-term cultivation of an advisor who can provide the level of care desired by the CFP Board a lower priority! Which does not align with the Fiduciary Standard of Care applied to all CFP professionals in October 2019.

Without More Formalized Experience Requirements, We Cannot Advance The Financial Planning Profession

Because of the lack of a formal process for advisors to gain relevant financial planning experience, the consumer experience with a CFP professional can range widely – serving as an obstacle to the CFP Board’s quest of bringing financial planning forward as a reliably identifiable and consistent profession in the eyes of consumers.

How would the service provided by a CFP professional who spent three years solely servicing employee benefits compare to the CFP professional who sat through hundreds of comprehensive planning meetings covering all areas of the planning process? Consumers should have an expectation that all CFP professionals have the broad experience required to meet their needs.

Additionally, is this fair to the Standard-pathway CFP professional who spends 6,000 hours outstandingly conquering all tasks set before them during their experience requirement phase? Would greater direction from the CFP Board increase the scope of exposure all candidates for CFP certification receive during their training period, or possibly lead them to be more discriminating in their choice of roles if their time served did not count toward the experience required to obtain the CFP mark?

How Medical Education Can Provide A Model For Building A Residency Program For New Advisors Entering The Financial Planning Profession

The knowledge necessary to create a standardized training program exists in conference discussions and firm practices across the country. And taking the step to formalize that knowledge into a comprehensive universal training program for all CFP candidates will elevate the CFP mark, financial planning consumer experiences, and the profession at large.

To this end, we can structure a residency-style training program that mirrors the training provided in medicine to educate new advisors. To create such a program, we should follow the model medicine uses for post-graduate training.

Formal training for physicians in the United States commenced in the 18th century at the University of Pennsylvania, when medical education still consisted mainly of just didactic lectures and medical students had to seek out apprenticeship opportunities separately. As medical schools popped up around the country, a lack of training consistency stymied the development of the profession for many decades. It wasn’t until after the Civil War that the framework of modern medical education was developed.

As medicine became more grounded in science, some program standardization followed. In 1910, a report sponsored by the Carnegie Foundation and supported by the American Medical Association shone a light on the need for uniform training that facilitated new standards for medical schools. It also recognized that burgeoning medical knowledge was increasing the need for training beyond medical school, which resulted in formal residency programs. The training of physicians has continued to morph over the past century to meet the needs of the public and medical providers.

The Role Of Medical Internship Programs And Accreditation Milestones

Medical school provides a mixture of didactic lectures, interactive training opportunities, and heavily supervised patient experiences. Medical school graduates can obtain a license to practice after a one-year internship (known as Post Graduate Year 1, or PGY-1) in a supervised program. However, most institutions and many states require that physicians maintain board certification in their specialty, which requires another two to six years of training past the internship year (PGY-2 through PGY-7). Additionally, physicians may complete additional fellowships to become highly trained in one specific area of their specialty.

The current model of accreditation is beginning to emphasize the resident reaching certain ‘milestones’ instead of just the amount of ‘time served’. The resident’s progress is tracked by monitoring education and achievements using real-time data that is documented by the resident and the residency program. This includes measures such as the number and types of procedures performed and hours completed in clinic, and provides opportunities for potential acceleration of certification for those who bring appropriate experience from other fields or who are highly motivated to graduate from their training.

Because of the consistent process in place for training medical professionals, the public has confidence that a board-certified physician has met a base of standards and has been determined to have the competence to use the credentials. That baseline standard allows the patient to search for the right physician based on additional standards such as personality fit, ease of access, and cost factors, often with less concern for the physician’s technical skills and ability to practice medicine.

The Administration Of Residency Programs

In the last year of medical school, students apply to interview with various residency programs. After formal interviews, the students rank their desired residency and the residency programs rank their desired students. “Match Day” occurs every March and students start their new programs in July.

Residency programs are provided both in university and community hospitals and in outpatient practice settings. All programs are approved and monitored by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). There are common program requirements regardless of specialty that outline oversight, personnel structure, education, evaluation of residents, and working environment. These program requirements are regularly reviewed by ACGME and updated to keep pace with societal and educational changes.

In addition to developing residency requirements, the ACGME is also charged with addressing workforce needs, especially in medically underserved areas and populations, and with clearing the way for new programs as needed to meet those needs. It also conducts occasional remote and in-person site visits to monitor a program’s compliance with ACGME requirements.

Beyond the general education requirements, the ACGME has specific requirements for different medical specialties and provides a structure for the attainment of unique milestones required to graduate from a program. This enables consistency of experience and teaching from program to program. These guidelines delineate required topics and skills and a minimum of dedicated time toward topics and skills.

Once a student graduates from an ACGME accredited program, they are then eligible for board certification in their specialty. Each specialty board provides a certifying exam and monitors the continuing education and training of practicing physicians.

Mechanics Of Residency Training

The length of residency is 3 to 7 years, depending on specialty. Non-surgical specialties tend to have shorter training periods than surgical specialties do. Residents rotate through different outpatient clinics and hospital services to learn about different areas of their specialty. Rotations are usually from 2 to 4 weeks between clinics and hospital services.

There is a hierarchy of responsibility for patient care. The PGY-1 interns interview patients, gather their data, and write patient notes, and these are all strictly monitored by higher-level residents. Higher-level residents answer to the lead physician, known as the attending. The main responsibility for patient care and outcomes falls on the attending.

In the hospital, each day the patient care team “rounds” on the patients. The care team consists of first-year interns, upper-level residents, and attending physicians. The intern arrives early to see the patient, pull up lab data, and enter the patient notes. The upper-level resident reviews the intern’s and lower-level resident’s work before rounds commence. During rounds, the intern presents the case to the team, including the attending. The attending and team check on the patient and the attending makes the final decision as to what is needed next for the patient.

Residents learn out-patient care in ambulatory clinic settings. They may consult with the attending if they have questions or concerns about the patient. One attending will supervise a number of residents during each clinic and will also review the medical records of patients seen by the residents. Primary care residents often have a patient panel, so both the patient and the resident experience the benefits of continuity. This tightly managed structure helps ensure quality care that is appropriate for the patient.

Didactic Training

In addition to clinical rotations, interns and residents have regularly scheduled didactic lectures, grand rounds discussing patient cases or major topics of interest, and hands-on practicums. These sessions are mostly delivered by the attendings and residents; although invited guests may sometimes give presentations.

The intention of medical education is to cover a wide breadth of subject matter throughout the years of training. The goal is two-fold – to prepare the resident with the depth of knowledge required to provide good patient care, and to cover all the topics that will be tested in their board certification.

Many programs have moved from predominantly traditional didactic lectures to more hands-on learning, workshops, and other interactive opportunities. With the advent of information readily available through the internet, programs are designing curricula that are linked to patient-care outcomes rather than the ability to recall discrete medical knowledge.

Physicians are required to continue their medical education throughout their career to maintain board certification and, in most instances, to maintain their license to practice in their state. This requirement can be met not only with didactic learning and repeated board examinations, but also with practice improvement activities. This continuing education further enhances competent delivery of care and public trust in the board certification process.

Application Of Medical Residency Program Structure To Financial Planning

Relative to the medical field, financial planning is a young profession. After World War II, the need for financial advice boomed. However, without a standardized system of teaching individuals how to give financial advice, the advice provided was fragmented and delivered by myriad professionals – brokers, insurance agents, attorneys, and accountants. In 1969, a group of individuals saw the need to have a profession dedicated to bringing integrated knowledge to the public. They created the College for Financial Planning and the International Association for Financial Planners (IAFP – which later merged with the Institute of Certified Financial Planners in 2002 to become the Financial Planning Association). In 1972, IAFP enrolled the first class of students into the Certified Financial Planners course.

Over the next decade, great strides were made in developing the body of knowledge needed to develop a profession. It was recognized that an educational institution such as the College for Financial Planning was not the appropriate entity to enforce ethical standards. To address this issue, it was determined that an independent, non-profit certifying board was important to move the profession forward. Thus, in 1985, the International Board of Standards and Practices for Certified Financial Planners, Inc. (IBCFP) was created. This is now known as the CFP Board.

Over the subsequent decades, the CFP Board has expanded the footprint of institutions offering the education required to obtain the CFP mark. There are now over 300 institutions registered with CFP Board that offer certificate or full degree programs in the United States, with masters and doctorate programs also available. The testing, education, and experience requirements have morphed throughout the years – at times becoming more stringent and, at other times, less rigorous.

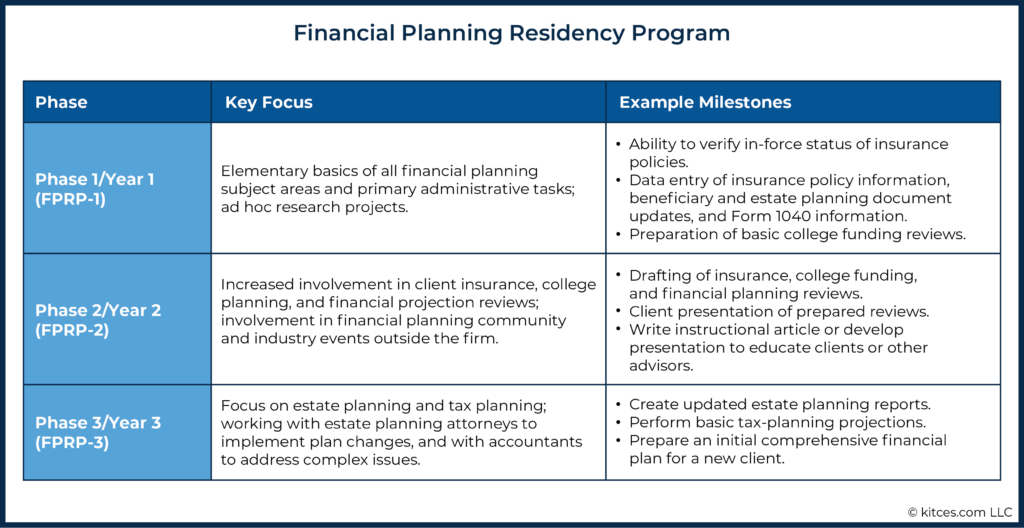

This situation very much mirrors the early years of medical education training, where an expansive body of knowledge is being passed through fairly standardized educational experiences, and the opportunities for training to apply that knowledge in real-world situations are sorely lacking. A small number of financial planning practices have created short-term positions to address this issue, but there is no standardized formal training process. Recognizing the need, our firm built a 3-year financial planning residency curriculum in three phases, to mirror the ACGME process applied in medicine.

Financial Planning Residency Phase 1 (FPRP-1)

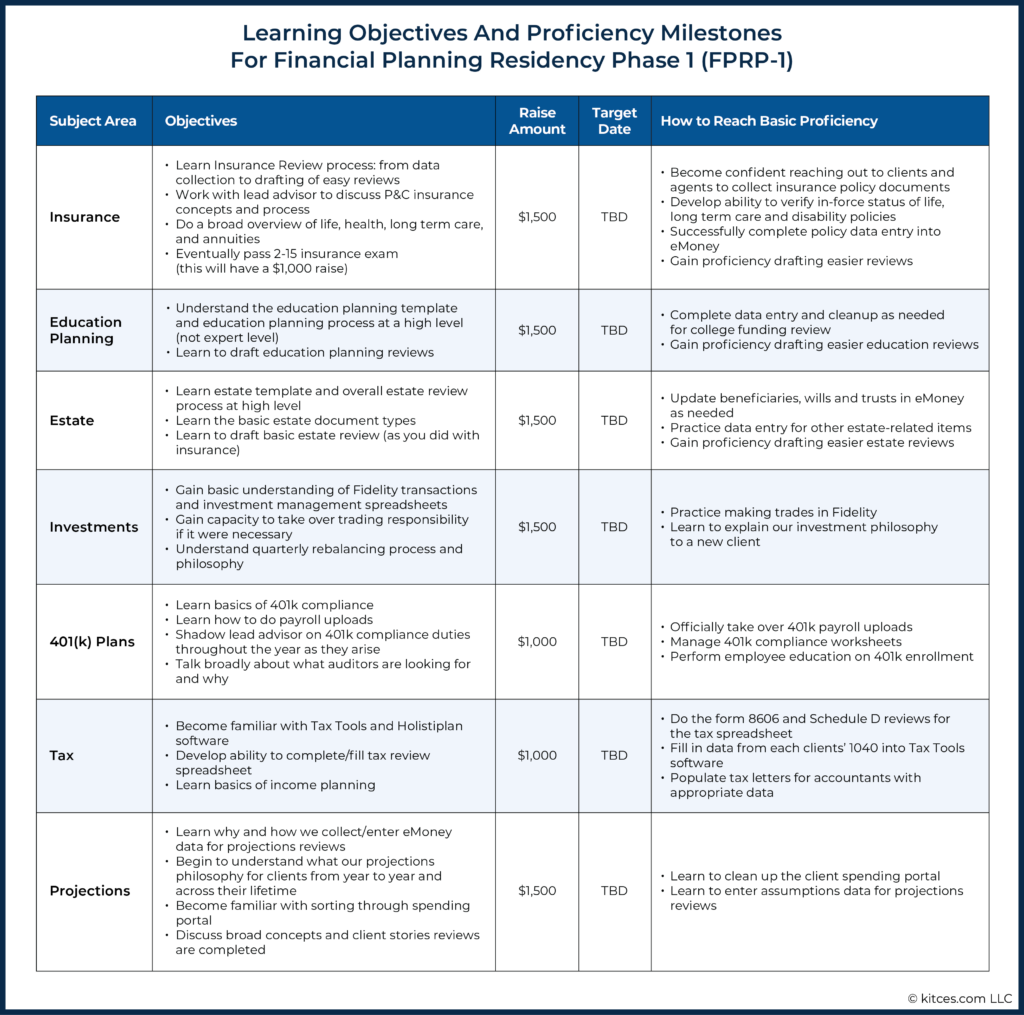

The first year of the financial planning residency, Financial Planning Residency Phase 1 (FPRP-1), focuses on the elementary real-world basics of all core planning ideas, including nuts and bolts administrative tasks. We provide the resident with learning objectives and the requirements to reach basic proficiency (see chart below).

Target dates when residents focus on particular subject areas are chosen based on the needs of the firm. For example, we intentionally have residents begin with insurance and education planning. With insurance, we reach out to agents and clients to gather policy information – although usually done by administrative support staff, this is an opportunity for the new advisor to have client interaction and learn how to work and communicate with consultants.

Once residents gain proficiency on the administrative items involving retrieving information from clients and verifying policy information, this duty is returned to the admin staff. The FPRP-1 then learns to input insurance policy data into financial planning software and draft the easier insurance reviews for clients. After proficiency is obtained in these areas, they receive a raise to celebrate their success. In our practice, since the state of Florida requires a 2-15 license to provide advice on insurance, we also provide a raise after this license is obtained.

As a new grad, the resident may have had their own recent experience in financing a college education. This gives them the confidence to tackle both the planning and conversations with clients about paying for education. Early client interaction is important to work on communication skills and it is fun for the advisor.

Other core areas are tackled at specific points in the year. Tax letter first drafts are created in November and December. 401(k) plan compliance has specific requirements in certain months. The remaining objectives are obtained throughout the year based on the motivation of the resident. It is expected that all objectives will be reached by the end of one year.

Other responsibilities of the FPRP-1 resident include one-off help with client tasks and research projects. In medicine, there are diseases that a resident will see only occasionally in their career, and they need the opportunity to learn about those outliers. We face the same dilemma in financial planning – recent examples in our firm include a client who was talked into buying a timeshare, and another client who received notice of an IRS audit. The FPRP-1 resident researched the timeshare situation quickly so the client could get out of the contract, and she is currently helping the other client gather the needed data for the IRS audit.

Financial Planning Residency Phase 2 (FPRP-2)

We address each part of the planning process as a team for every client throughout the year – reviewing insurance, investments, and estate plans; updating financial projections and cash flow needs; and tax planning. The client is contacted about each review to get their input in advance of creating the update, and a report is sent to the client with recommendations for changes required. If needed or requested by the client, we’ll review the report with them through a phone call, video, or in-person meeting. The second year of the residency is Financial Planning Residency Phase 2 (FPRP-2), in which residents have increased levels of responsibility for these processes.

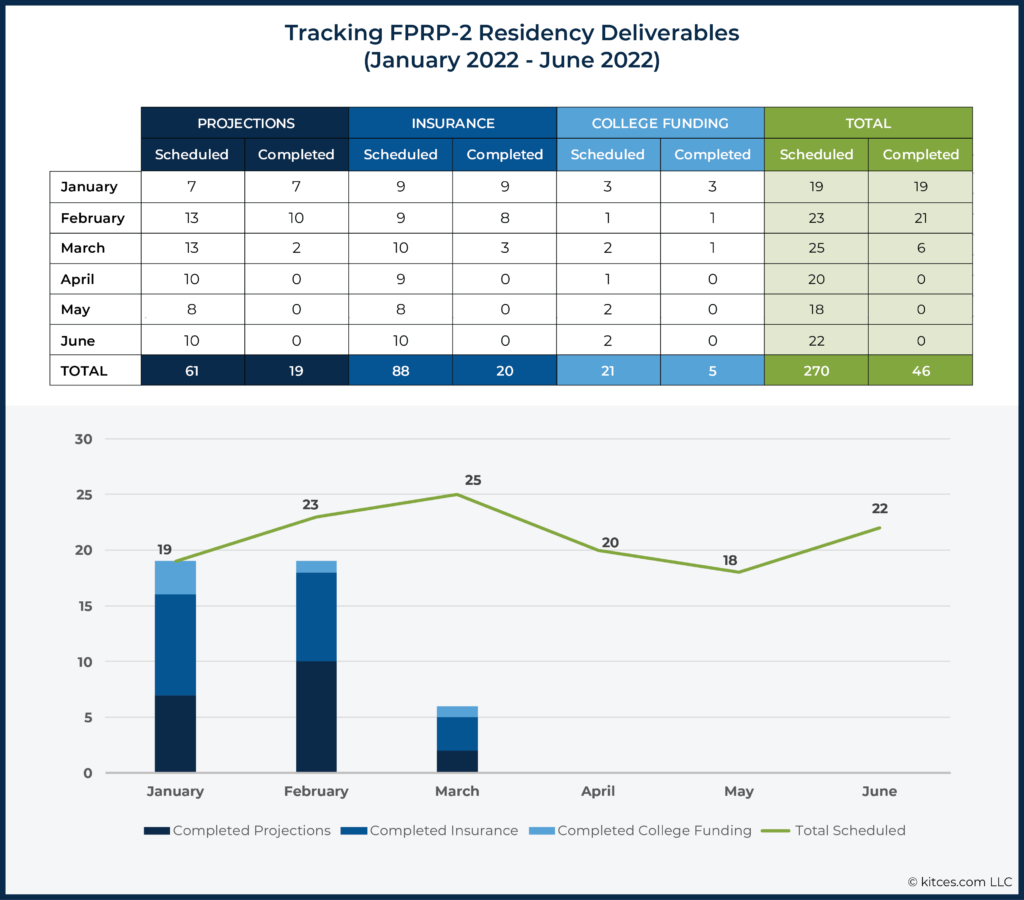

Our firm maintains a spreadsheet that outlines the report deliverables throughout the year and allows residents to track their progress. The resident is tasked with managing their workflow and entering the date of completed projects on the spreadsheet. The FPRP-2 is responsible for the insurance, college planning, and projection reviews. They are assisted by the FPRP-1 in gathering data and producing the report. As reports are completed, they are reviewed by the ‘attending’ planner. The report is signed by both the resident and attending and sent to the client by the resident.

When a client meeting occurs, the resident is in charge of presenting the report information to the client. All planners are in most client meetings – the number of actual in-depth meetings is less than one a year on average per client. Since our communication throughout the year is intentional and frequent, these meetings mostly entail life discussions and presentations of the area of planning that stimulated the need to meet.

Investments in our firm are managed by our in-house CFA. The residents work with him to understand the client’s investment policy and assist in meetings on client investment education. They are also trained on trading and rebalancing so they can assist in the event the CFA is not available.

In addition to drafting and presenting client reviews, the FPRP-2 is responsible for the tasks generated by the reviews, such as shopping for new insurance. They also assist clients with common tasks, such as employee benefits enrollment, mortgage research and application, and major purchase assistance.

The FPRP-2 is encouraged to write articles and develop presentations for other advisors or for clients. It is our belief that involvement in the industry outside the firm is an important component of elevating financial planning as a profession.

Financial Planning Residency Phase 3 (FPRP-3)

In the last year of the program, Financial Planning Residency Phase 3 (FPRP-3) residents take on the responsibilities of estate planning and tax planning. Since these two areas contain significantly more nuance in understanding the client's situation and the constantly changing rules, it is more challenging to let the resident operate entirely independently during this one-year immersion.

Estate planning responsibilities include creating an updated estate report, checking for changes in assets to ascertain appropriate titling and beneficiary designations, and working with the estate planning attorney to implement any needed changes.

Tax planning involves a review of the prior-year tax return, verification of appropriate retirement plan contributions, planning optimal retirement plan distributions, tax withholding, and present and future tax efficiency. More complicated tax issues will entail working closely with the accountant.

The key to comfort with this increasing level of client-facing responsibility is that our corporate engagement standards are adhered to strictly. Our insistence on good communication, teamwork, reliability, and integrity sets the tone for a resident to step out of their comfort zone, knowing they are totally supported by the team.

Being a financial planner is very similar to being a family physician – a practitioner has to be adept at handling the common situations, which encompass about 95% of client encounters. It is also important to recognize critical situations so that assistance from specialists is obtained early before disasters occur.

And finally, for anything that is not clearly common, the practitioner should have good relationships with specialists – in the case of personal finance, we frequently consult with accountants, attorneys, insurance agents, and therapists. The residents facilitate many of these conversations to increase their exposure to higher-level issues.

Practice management is included in the residency through multiple experiences. We have regular meetings for compliance, business planning, and review of the company's financial status. Residents are encouraged to participate in press opportunities and other marketing events. This open dialogue is foreign to many practices, yet it is important for the well-rounded development of the next generation.

Our future vision for financial planning residencies is for these programs to be implemented as a joint effort of multiple firms who actively use residencies in their practices. And in order to get there, our next step is to create a formalized structure of regularly available didactic programs. These programs could be presented remotely by the residency firms themselves and backed by the CFP Board.

Eventually, we could even have an organization for the teachers of financial planning, including those in residencies and academic institutions. Such an organization could be developed to offer a forum to help educators collaborate and create a standardized, high-quality didactic curriculum, similar to the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine who advocate high-quality family medicine education and training.

It took over a century to formalize the training of doctors, and that training continues to grow and evolve. By using the medical field as a guide to create valuable residency programs, we can ideally come full circle with our own profession, developing an educational structure that will help consumers – and practitioners! – to recognize financial planning as the esteemed profession that provides clients with critical services that they need and deserve!