Executive Summary

From the moment the Roth IRA was created in the late 1990s, it has been a popular vehicle to generate future tax-free growth and income, whether by contributing to the account on an ongoing basis, or even doing a Roth conversion of an existing IRA or other pre-tax retirement account.

Yet the caveat is that the decision to contribute or convert to a Roth IRA incurs an immediate tax liability. And in the extreme, a large Roth conversion can generate so much taxable income that it actually drives up the IRA owner’s tax bracket to the point that the transaction becomes wealth destructive!

Fortunately, though, the decision to do a Roth conversion doesn’t have to be “all or none” – and in fact, not only is a “partial” Roth conversion permitted, but in practice it’s often the optimal strategy, allowing retirement account owners to convert just enough to fill the lower tax brackets, without causing “too much” income that would trigger the top tax brackets.

In fact, the Roth recharacterization rules make it feasible to precisely fill the bottom tax brackets, but not a dollar more, by converting more than enough to fill the lower tax brackets each year, and then doing a partial recharacterization to back into the optimal partial Roth conversion amount after the year is over!

How To Do A Partial Roth IRA Conversion – It Doesn’t Have To Be All Or None!

Beginning in 1998, taxpayers have been permitted to both contribute to a Roth IRA (subject to income limits), and to convert existing assets in a traditional pre-tax IRA to a Roth. In 2006, under the Pension Protection Act (and the subsequent IRS Notice 2008-30), the Roth rules were further expanded to allow conversions of pre-tax 401(k) plans directly to a Roth IRA. And in 2010, delayed provisions from the Tax Increase Prevention And Reconciliation Act of 2005 finally took effect, eliminating Roth conversion income limits altogether, allowing anyone with a pre-tax retirement account – IRA or 401(k) (or any other employer retirement plan) – to convert to a Roth IRA (or even intra-plan to a Roth 401(k)).

Notably, though, while the Roth conversion rules are often discussed as though an entire IRA or other pre-tax retirement account might be converted, the reality is that IRC Section 408A(d)(3) simply stipulates that whatever dollar amounts are distributed to a pre-tax IRA and rolled into a Roth will be treated as taxable as a Roth conversion. There’s no minimum or maximum regarding how much must be converted. In other words, a Roth conversion doesn’t have to be all or none; it’s up to the investor/taxpayer to decide whether to convert everything, or to simply do a “partial Roth conversion” instead.

Similarly, under the Roth recharacterization rules of Treasury Regulation 1.408A-5, any Roth conversion amounts that are rolled back to a pre-tax IRA (in a timely manner by the following-year-October 15th deadline) are no longer taxed as a Roth conversion. Yet again, there’s no requirement that a recharacterization be all or none; instead, the account owner can recharacterize as little or as much as desired (with the caveat that all amounts recharacterized must share in a pro-rata portion of any gains or losses, unless the Roth conversion was done to separate accounts in the first place). Thus, even a pre-tax retirement account that is fully converted to a Roth can end out being a partial Roth conversion, if partially unwound via a partial recharacterization!

The fundamental point: Roth conversions really don’t have to be an all-or-none transaction, and can either be done as a partial Roth conversion on a prospective basis, or partially recharacterized after the fact to create the same result. And in practice, doing a partial Roth conversion – or rather, a series of them – is often the best way to maximize the long-term value of a pre-tax retirement account!

Using Partial Roth Conversions To Fill Lower Tax Brackets

The virtue of doing a Roth conversion is that once converted, subsequent growth in the account can be spent tax-free as a qualified Roth distribution in the future. The caveat, of course, is that doing the Roth conversion forces the value of the account to be reported as income today, triggering an immediate tax liability. To come out ahead, the current tax rate at the time of conversion must be lower than what the marginal tax rate would be in the future.

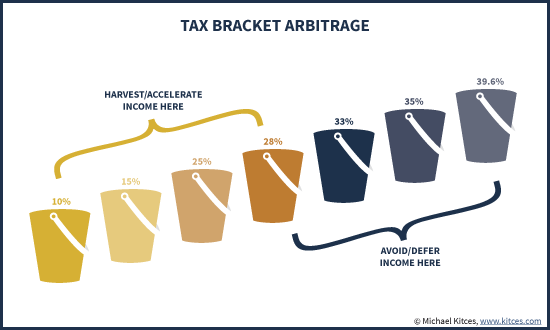

Yet given that a Roth conversion itself is income for tax purposes, a large single-year Roth conversion can become self-defeating; because tax brackets are progressive (the higher the income, the higher the tax rate), if enough dollars are converted at once, so much income is created that the taxpayer is driven into the top tax brackets. Which ironically means there really is such thing as doing “too much” of a Roth conversion, where the effort to create a large tax-free account all at once with a huge conversion drives up tax rates to the point of making it less desirable (or outright destructive!) in the long run to have done so!

Example 1. Jeremy and Linda’s current combined income after deductions is $60,000, putting them in the 15% tax bracket. They have a $500,000 IRA that they are considering whether to convert to a Roth IRA to avoid what is anticipated to be a 28% marginal tax rate in the future when their RMDs begin. If they convert the entire account, though, their taxable income will be increased to $560,000, driving them up into the top tax bracket of 39.6%. Which means a Roth conversion that may have been appealing initially (converting at 15% to avoid a future 28% rate) becomes very unappealing by the end (as the last ~$100,000 crosses into the 39.6% tax bracket today, just to avoid a lower 28% rate in the future!).

In this context, the partial Roth conversion suddenly becomes appealing. Converting the entire account may drive the couple’s marginal tax rate into the top 39.6% bracket, which is so high that they probably would have been better off just leaving the money as a pre-tax IRA and spending it in the future at a lower rate! A partial Roth conversion, on the other hand, allows the couple to create just enough income to be subject to the lower tax brackets, while stopping before they reach the upper brackets.

Example 2. Continuing the prior example, Jeremy and Linda could convert as much as $14,900 and still remain within the 15% tax bracket (which tops out at $74,900 for a married couple in 2015). Alternatively, the couple might choose to convert as much as $91,200, filling up the remainder of the 15% bracket and all of the 25% bracket (which ends at $151,200 for married couples filing jointly), but stopping before they ever actually hit the 28% bracket today. Thus, the couple is avoiding the top tax brackets today, while also avoiding an anticipated future 28% tax bracket for those converted dollars paid at 15% or 25% now!

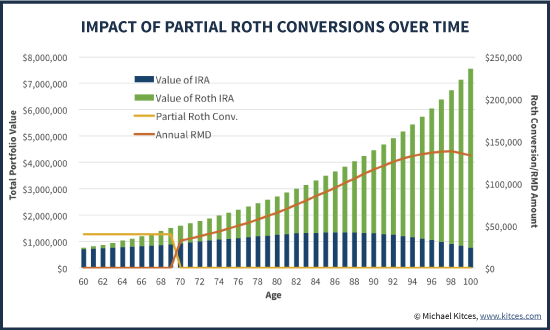

The end result of the strategy is that the couple can convert exactly enough to ensure that their IRA is subject to the lower tax brackets today, but only those lower and more favorable tax rates. Of course, given that there’s only so much room to convert until the higher brackets are reached, this means the bulk of the couple’s IRA may remain in pre-tax form. Yet given a multi-year – or even a multi-decade – time horizon before they need to spend/use all the money, this isn’t necessarily a problem. It simply means the couple will repeat the partial Roth conversion systematically each year in the future as well, continuing to whittle down the size of the pre-tax IRA (and grow the size of the Roth IRA), while ensuring each year that the conversions are modest enough to avoid ever hitting the top tax brackets.

Ultimately, then, the goal of partial Roth conversions is to find a balance, where the converted amount is low enough to avoid top tax rates today, but not so little that the remaining retirement account balance plus compounding growth causes it to be exposed to top tax brackets in the future, either.

Identifying Low Tax Rate Opportunities For Partial Roth Conversions

Clearly, one challenge to the strategy of Roth conversions is that the benefits are highly dependent on what future marginal tax rates turn out to be, in a world where we don’t necessarily know that outcome for certain as of today. Projecting future wealth and known future income streams can be a good starting point for estimating a future marginal tax rate (e.g., what will tax rates be for the retiree who already has Social Security benefits, portfolio interest and dividends, real estate or other passive income sources, and/or Required Minimum Distributions [RMDs]), but clearly some uncertainty remains, not the least because Congress could just outright change the tax laws between now and then (although even higher tax rates in the future is not a guarantee that Roth conversions are a good idea today!).

Nonetheless, we can know what the marginal tax rate will be for this year, and in practice there are many situations where that tax bracket is low enough that we can be virtually certain it is favorable compared to almost any likely future.

For instance, if someone experiences a layoff that leaves them without employment income for most of the year, his/her tax bracket may be just 10% or 15%, a rate that’s hard to beat in any foreseeable future as long as there’s any income tax system. In the extreme, if deductible household expenditures (e.g., property taxes, charitable giving, the deductible portion of advisory fees, etc.) continue while there’s no income for the year, taxable income could even be negative, which means the partial Roth conversion would be tax-free just absorbing the otherwise-unusable deductions (which are permanently lost if not offset against negative income in the same tax year!).

Similarly, a business owner that experiences a significant (pass-through and otherwise deductible) business loss might have an ‘unusually low’ income year where a partial Roth conversion can benefit at the low rate. Alternatively, a household that has an unusually large amount of deductions (e.g., for a significant charitable contribution, or perhaps paying a large outstanding state tax liability balance from the prior year?). And notably, because deductions are applied against ordinary income first and capital gains second, someone with high total income due to capital gains could still be eligible for low tax rates on a partial Roth conversion (although this can still phase out the benefits of 0% long-term capital gains tax rates), and/or have their deductions apply favorably to shelter further partial Roth conversions.

Systematically Repeating Partial Roth Conversions Of An Existing IRA

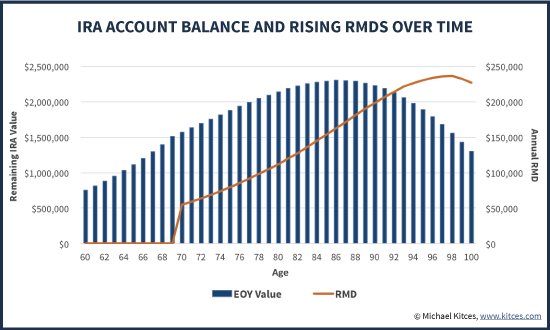

For those transitioning into retirement, the years after wages and employment income end, but before Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) obligations kick in, can also be especially appealing for timing partial Roth conversions. For instance, a retiree in their early 60s might do a partial Roth conversion each year throughout their 60s, whittling down the size of a pre-tax IRA over time, such that by the time RMDs actually begin at age 70 ½, there isn’t much of a pre-tax IRA left!

Example 3. Betsy is a single 60-year-old female who recently retired with a $20,000/year Social Security survivorship payment and a $40,000/year survivorship pension from her deceased husband. Betsy also has a $200,000 brokerage account, and a substantial $700,000 IRA (the combined value of her original IRA, and a spousal rollover from her deceased husband’s 401(k)). In a decade when her RMDs begin, Betsy will face RMDs of upwards of $50,000/year (with an 8% growth rate in the IRA between now and then), propelling her into the 28% tax bracket even after her moderate deductions; by her 80s, the RMDs are projected to be more than $100,000/year, topping out the 28% rate and approaching the 33% bracket!

To manage the exposure, Betsy decides to do a partial Roth conversion of $40,000 each year for the next 10 years, which after her deductions just barely fills up her current 25% tax bracket, but stops short of the 28% tax rate. Repeated each year, this gives Betsy the opportunity to significantly whittle down her overall IRA exposure; in fact at this pace, her pre-tax IRA will still only be about $900,000 by the time her RMDs begin, which will produce RMDs of barely $35,000, allowing her to remain in the 25% tax bracket! In the meantime, Betsy will have accumulated a tax-free Roth IRA projected to have grown over $700,000 by age 70 ½!

The end result – by doing systematic partial Roth conversions for several years in a row, it’s possible to remain in (and fully utilize) the lower tax brackets, while avoiding higher tax rates today, and whittling down pre-tax retirement accounts to the point that RMDs won’t be subject to higher tax rates in the future, either!

Filling The Lower Tax Brackets – Using Roth Recharacterizations To Avoid Losing Them

The key aspect of the systematic partial Roth conversion is that deferring “too much” income – by accumulating and compounding an IRA and never withdrawing or converting it – drives someone into top tax brackets, and there’s no way to go back after the fact and use lower tax brackets that may have been available in prior years. In essence, a low tax bracket available today is “lost” forever if not actually used in the current tax year. Which means for those who are already facing top tax rates, it makes sense to defer or avoid income, but for those eligible for lower tax brackets, it’s an opportunity to harvest income, accelerating future income into today’s lower marginal tax rate.

And notably, since the opportunity to fill low tax brackets is a “use it or lose it” scenario – because taxable events must actually occur in the current tax year to count in those income buckets – December 31st becomes a firm deadline for any annual low-tax-bucket-filling strategies.

Unfortunately, deciding how much income to create before the end of the year can be challenging, because sometimes you don’t know what income (and deductions) will end out being until the very end of the year, leaving little or no time to do the calculations and the ‘last minute’ conversion.

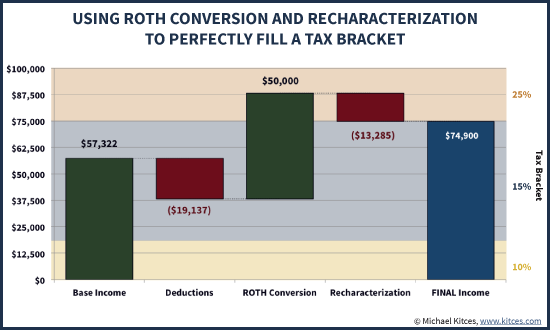

In this regard, the particular strategy of doing Roth conversions with a planned recharacterization becomes appealing. Because the Roth recharacterization rules allow a Roth conversion to be undone in the following tax year (as late as October 15th), those who aren’t certain how much to convert to fill the bottom tax brackets can simply convert more than enough now, and then recharacterize the excess later!

Example 4. Donald and Donna are retired and have approximately $50,000 of current income and $15,000 of deductions, and want to do a Roth conversion to fill their 15% tax bracket (which ends at $74,900 of taxable income). However, their nearly $1,000,000 portfolio in a taxable account holds several mutual funds that could make end-of-year capital gains and dividend distributions, and they’re not certain how much (if any) will be distributed until very late in the year.

To avoid the risk that the distributions will be small enough to allow room for a Roth conversion but come so late in the year there’s no time to do one, Donald and Donna do a partial Roth conversion, now, of $50,000, which would be sufficient to fill their 15% tax bracket even if total distributions from their investments turn out to be $0.

After the close of the tax year, it turns out that Donald and Donna have total income of exactly $57,322 and total deductions of $19,137. Their taxable income is $38,185, which means they could have converted exactly $36,715 of their IRA and still remained within the 15% tax bracket. Accordingly, they recharacterize $13,285 of their $50,000 Roth conversion (plus or minus the pro-rata share of any gains/losses from that $13,285 conversion), which results in a taxable Roth conversion of $50,000 - $13,285 = $36,715, the exact dollar amount they wanted to convert.

The end result of this strategy is that even in situations where there is uncertainty about exactly how much to convert, the precise amount of the desired partial Roth conversion can still be accomplished, by converting more than enough up front, and then recharacterizing the excess afterwards! Or in the extreme, the couple could convert even more investments, across multiple asset classes, into separate accounts, and then recharacterize everything except the account that is up the most, in the exact (original) dollar amount desired to fill the appropriate tax bracket(s)!

Carefully Evaluate True Marginal Tax Rates For Potential Partial Roth IRA Conversions

Of course, the caveat to all of this is that it’s still necessary to determine the ideal tax bracket, or amount of income, to partially convert to a Roth in the first place. Ultimately, this is driven not only by an estimate of the future marginal tax rate when the funds will be withdrawn (or if the IRA will be unused and bequeathed to the next generation, the marginal tax rate of the IRA beneficiaries instead!), but also the marginal tax rate today, including the impact of all the various income-related factors that can drive up marginal tax rates, from the impact of PEP and Pease, to the phase-in of taxable Social Security benefits, to Medicare Part B and Part D premium surcharges, AMT exposure, and more. In other words, just because someone is in the 25% tax bracket doesn’t necessarily mean he/she is really subject to a 25% marginal tax rate, as it could be much worse!

It’s also important to recognize and remember that Roth conversions will themselves impact future tax rates, as the diminishment of a pre-tax IRA reduces future tax exposure! For IRA accounts that are projected to be large – where RMDs can propel the IRA owner into the top tax brackets – a partial Roth conversion is appealing to benefit from lower tax brackets today and avoid the higher ones in the future. But notably, if the entire IRA is converted to a Roth, it eliminates all future tax exposure, which means the future marginal tax rate may become so low that the last IRA dollars weren’t going to be taxable anyway! In other words, the greater the (partial) Roth conversion, the less need there is to convert the remainder!

The bottom line, though, is simply this: the availability of low tax brackets is an opportunity that should be utilized before it is lost, and the partial Roth conversion (or a Roth conversion followed by a partial recharacterization) is a flexible strategy to ensure that those low tax rate buckets never go to waste!

So what do you think? Do you engage in partial Roth conversion strategies systematically with your clients every year? How do you figure out the amount to convert each year?

We used to engage in partial ROTH conversions each year up to the 15% tax bracket. This allowed us to take advantage of the 0% rate on long term cap gains. But now, in the post PPACA era, the decision to make partial ROTH conversions is not as clear.

My wife and I retired early and our income is solely from

mutual fund distributions. Some years, that income could be low enough

to make us eligible for some PPACA subsidies. For those years, I have not figured out if it is more advantageous to do a partial ROTH conversion up

to the 10% or 15% tax brackets and give up the subsidies, or defer the

ROTH conversions.

Any advice on how to go about determining which is the better strategy?

I love reading your blog. Thank you for making it available to me.

“Subsidies”?

Perhaps you should not look for taxpayer handouts in your retirement, and instead pay your fair share-all by yourself?

And, if your income is so low as to at times qualify for subsidies, and you said you retired young?

Perhaps you go back and work (like the rest of us), to both earn more, and save more?

As you may gleam from my reply, it is only natural for other taxpayers to resent people who ask for handouts, because they chose to intentionally retire early and enjoy themselves, and then ask others who do work, to pick your your healthcare tab via a “subsidy” to you.

No, no, the leeches are people who play these tax optimization games and don’t maximize their income tax bill! … Not. “How long is a minute depends on which side of the bathroom door you are on.”

Cedric,

See https://www.kitces.com/blog/how-the-premium-assistance-tax-credit-for-health-insurance-impacts-the-marginal-tax-rate/ for some discussion of how rising income (including from Roth conversions) is adversely impacted when you’re eligible for premium assistance tax credits.

The short answer is that phasing out the premium assistance tax credit is the equivalent of a significant surtax on income, and makes Roth conversions drastically less appealing. :/ So you may find it’s preferable to delay Roth conversions until you switch over to Medicare and the premium assistance tax credits are a moot point.

– Michael

Thank you. Much appreciated.

– c.

We have been implementing this strategy for our early retirees for several years now. Having TaxTools software to fun the various scenarios and figure out how much to convert each year has helped, but I can see the value of just picking an approximate number and recharacterizing later. The number I tried to get when doing this analysis for clients was “total lifetime taxes paid (from this point forward)” for each Roth Conversion strategy. We even tried building our own spreadsheet to do this, but it quickly got too complicated. And, as you pointed out Michael, we have to make a bunch of assumptions anyway, so what is the value of trying to be that exact? Bottom line–it’s a sound strategy that will save on taxes, especially for our clients that are in the “golden decade” of their 60’s and have already retired. And, it’s a strategy that is pretty easy to explain and that our clients understand.

I have implemented this strategy for the last 7 years. When I retired & had enough of golf (or just started playing a little worse than before), I developed a software program that mathematically quantifies the amounts to potentially convert each year prior to RMDs. My program results in a side-by-side comparison of my clients retirement plan against my program’s strategic plan that incorporates partial Roth conversions using the exact assumptions (like rates-of-return, income, expenses, etc). We identify a recommended outlook for potential Roth conversions for the entire planning period (up to 20 years). We identify actual and real benefits that potentially might be realized with respect to monetary net wealth (MNW – what’s yours to keep after all taxes are paid), and tax-savings benefits. In addition, once the optimal amount is identified each year, our various conversion strategies (none of which have been mentioned in this article as well as different from John D. Bledsoe’s strategies mentioned in his book “The Gospel of Roth”) have proven to be very successful. See Invision20.com for more info ….

I have been doing partial Roth conversions for the past 8 years. I wrote an Excel spreadsheet which connects to the Solver optimizer and calculates the optimal amount to convert. The inputs to the optimizer are the Federal and NY State tax rates as well as projected returns for both taxable and non taxable accounts. The program is not perfect. For example the first version failed to account for AMT, But as you stated in your article you always have the option to recharacterize which I did when I found out that due to AMT I was in a much higher tax bracket than projected. Over the past eight years I converted over 1/3 of my IRA to Roth. I plan to continue but also as you mentioned I do not want to totally deplete my IRA as I need the income to offset deductions.

Maybe I am missing something, but how would one end up in the AMT with taxable income (married couple filing jointly) of around $75,000? It would seem that would require a pretty unusual (and therefore one-off) set of circumstances right?

You’d need to have capital gains or something else on top to trigger AMT at $75,000 of gross income (at least for a married couple). But depending on income/wealth, not everyone fills “just” the 15% bracket. Some might fill 25% or 28%, which puts them more squarely in “AMT-land”…

– Michael

Hi Steve, I know you wrote this years ago, however, is there anyway that you could share this excel with me? I would love to use it myself!

To go one step further, Roth conversions do not have to end once a person reaches 70 1/2 and starts their IRA RMD. While they cannot convert the RMD portion to a Roth IRA, they could still convert IRA money above the RMD amount. This is particularly useful if one intends to let the Roth IRA pass to their beneficiaries. A Roth IRA beneficiary is only required to take RMDs based on their life expectancy, a.k.a. stretch IRA, so much of it continues to grow tax free for a long time.

Also, if one were feeling charitable, and if Congress extends the law that allows for taxpayers to donate to charities directly from their IRA RMD, one could lessen the impact of the that the RMD has on their AGI by giving some of the distribution away, i.e. this is an above the line tax deduction. By doing so, this would allow them to convert even more of their IRA to a Roth without going into the higher tax brackets.

First thanks for this review of various strategies and options for conversion of an IRA to a ROTH. However, I have yet to see a discussion on those couples who have taxable ordinary income, after deductions, that put them in the 15% tax bracket (under $74,900). And, in addition they have capital gains that take them up to and over the $74,900 tax bracket. So part of their capital gains would be ‘taxed’ at 0% and part at 15%. When you do the math, any IRA conversion to the top of the 15% bracket would be taxed at the 15% ordinary rate and any equivilent capital gains dollars enjoying the 0% capital gains tax rate would then be taxed at 15% as they get pushed above the $74,900 tax bracket limit for the 0% rate. Therefore, for each $100 in IRA conversion, there is at least $15 in ordinary income tax and another $15 in capital gains tax – making a total of $30 in taxes, or a 30% marginal rate. In the case of someone in this situation, I cannot see why they would do an IRA conversion in those years – since it is cheaper – tax wise – to wait until they are in a higher tax bracket – 25% for instance – where they no longer receive the benefit of the 0% capital gains rate. Am I missing something?

Eddie,

I wrote about the issue of how adding ordinary income that pushes long-term capital gains OUT of the bottom tax brackets can result in a 30% marginal tax rate (15% for the ordinary income in the lower bracket, and 15% for the capital gains pushed OUT of that bracket). See https://www.kitces.com/blog/understanding-the-mechanics-of-the-0-long-term-capital-gains-tax-rate-how-to-harvest-capital-gains-for-a-free-step-up-in-basis/ for further discussion of these mechanics.

Though you have a good point that I may need to delve further into that again specifically in this Roth conversion context! Stay tuned for a future article? 🙂

– Michael

Thanks, your referenced blog was spot on! Not many folks write about this anomaly in the code. Great blogs!

First, great article!

Second, good point raised by Eddie. However, is this not fairly easy to prevent (admittedly, I am an individual investor, and therefore, I only have to do the modeling for one taxpayer)? In other words, is not the “solve for” amount of the Roth conversion simply the amount which takes a married couples filing jointly taxable income above the $74,900 (using current tax brackets) once all other items of income and deduction have been accounted for? If I have this right, it should be fairly easily to model this in an excel spreadsheet and get close enough (with a final true-up/re-characterization after year end) to prevent pushing LT capital gains from the 0% to the 15% tax bracket?

I agree with Eddie. An article that discusses the coordination between Roth Conversions and capital gains and managing marginal rates would be good. Particularly, what to do if you are in the 15% bracket and have capital gains and what do do if you’re in the 25% bracket and have capital gains. Overall, I decision tree/framework would be extremely helpful.

I’m 67 and am waiting on SS until I’m 70 and won’t be taking RMD’s until 2019. So I have a time period where my taxable income is lower than it will be in the future.

I have engaged in systematic Roth conversions since the income cap was lifted in 2010. I could probably write a couple of pages on potential future events that could make my decision a good one or a bad one. But those events (like the marginal tax rate of your children in 30 years??) can’t be known with any certainty. When I’m faced with uncertainty, I think diversification is in order, so the Roth conversions represent tax diversification. One of my other key considerations is that there is a reasonable probability that a surviving spouse could live for an extended time after the death of the first partner which could result in much higher marginal tax rates and Medicare payments.

The manner for doing Roth conversions is similar to the methods you mention above.

– I use a self-developed personal financial plan that allows me to estimate how much I am planning to convert. After running multiple scenarios, I have settled on a plan where I hold constant my Modified AGI over the plan period. In general, I use marginal tax rates but mostly the step-function breakpoints for Medicare payments to establish the MAGI target. I then back into the Roth conversions.

– I have 5 Roth accounts — 4 current year accounts with different asset types, and 1 consolidation account.

– Each January, I stuff in much more than what I will be converting into these accounts. In December, I do a pulse check on the assets. If they are all down, I might throw in more conversions in a new account, and then recharacterize the ones put in earlier in the year.

– After I finalize my taxes, I determine the exact amount of the conversions; prioritize by % increase; move those assets into the consolidation account, and recharacterize the rest. Although I could hold out until October, that would require filing an amended return, and I prefer to get things finalized by April 15.

– This process is tedious, but once you get into a routine, not difficult.

Impressive.

I am new to retirement this year and looking at starting my conversions, you have given me a lot to consider and much I don’t quite understand.

A lot more could be said about the phase-in of taxable Social Security benefits – especially for those who live solely on Social Security and IRA/401(k) distributions. A 7-10 year Roth Conversion strategy in someones sixties could save them an extraordinary amount of taxes through out their retirement because of how SS benefits are treated for taxes (above and beyond what Kitces emphasizes in this article). Unfortunately, the income tiers for SS tax calculations are static and do not adjust with inflation – so this will become an moot point as inflation forces retirees to spend more (Might be a while though). I would love to see a case study on this.

Do you have a general feeling if it’s better to max out the 15% tax bracket with Roth IRA conversions or to realize capital gains to take advantage of the 0% LTCG rate?

I’m sure this is a dumb question, but let me ask …. Since we are talking about taxes for a married couple, is it necessary for the Roth Conversions from deferred income accounts be performed equally for both spouses? Another words, if the married couple are converting $40,000, then does each spouse move $20,000 from their respective traditional IRA’s to the Roth IRA’s?

Pedro,

As a married couple filing jointly, it doesn’t matter whose IRA account the monies come from, they’re on the tax return just the same. So if your goal is to convert $40,000, it doesn’t matter whether it’s all $40k from one person’s IRA, the other’s, a split, etc.

Though in terms of that person’s OWN IRA account, each person still handles RMDs on their own. So if one person is closer to 70 1/2 already and closer to RMDs, it’s probably more desirable to convert his/her account first. 😉

– Michael

A collateral (asset location) strategy is to have as much of the high growth asset classes end up in the Roth and taxable accounts and have the low growth (bonds) end up in the traditional IRA. Then, the IRA never really grows, as the RMD’s remove all the growth. First RMD is about 3.6% – which is above today’s bond yields and right around traditional bond yields. A good way to do this is with in kind conversions of various equities.

What is the timing for Roth conversion? Is it the April 15th (18th for 2017) date to do the conversion as it is for IRA or Roth contributions?

For a Roth conversion to count in a particular tax year, it must actually be done IN that tax year. So for normal calendar-year taxpayers, your deadline is that the conversion itself must be done by December 31st. The extended deadline by April 15th to do a “prior year” contribution does not exist to create a “prior year” Roth conversion; if you convert between January 1st and April 15th, it’s a Roth conversion for that year (the same as a Roth conversion on any other day of that year).

– Michael

Michael,

Most of my retirement clients have a pension, SS and fairly large 401(k) accounts. Sometimes their cash flow projections show them using very little of the qualified money to meet spending goals. Over time, the RMDs are projected to push them into very high tax brackets. Is this a ‘sleeper’ issue that was not foreseen for folks who have 401(k) accounts, a pension, and SS? This can be especially problematic for couples who each have full retirement benefits.

Very good article. A lot of variables that go into this plan, but typically a winner in most scenarios.

An excellent article as I am at the point of possibly needing to reduce my MAGI level for 2017 tax year to the amount below $85,000 to avoid an increase in my Medicare IRMAA Premium for 2019. I work part-time and it is difficult to know precisely what my earned income will end up being for 2017. I am single and over 70 years of age.

In addition to my retirement, earned income, interest and dividend income I will have the following income in 2017:

– a cash payment of approximately $5,000 related to a mandatory sale of stock in a stock reorganization (this will be a long term capital gain);

– a RMD of $2,100;

– a Roth conversion of $6,200.

My rough calculation of my MAGI for 2017 is that it will fall somewhat above the $85,000 level. So, it appears to me that the only variables I can control are to – a. reduce or terminate my pt employment (I don’t feel comfortable doing that) or – b. re-characterize enough of the $6,200 conversion of 2017 to reduce the MAGI to below $85,000.

Am I correct in those assumptions?

Question – Does the re-characterization need to be completed in the time period of the tax return for that year or can it be done in an amended tax return provided the amended return is filed prior to Oct. 15, 2018?

Second question / request for advice. I use Turbo Tax every year, it is convenient and does the job for me. However, unless I am missing something with Turbo Tax, I do not get to see my exact AGI until after I have completed and filed the federal tax return. What are the recommendations for me to be confident of what my AGI is prior to filing my tax returns?

Thanks in advance for any advice / assistance on this.

How does the 5 year rule come into play when one does yearly conversions from a 401K to a Roth IRA? Does it mean that you must wait 5 years after doing the last one in order to touch funds from the first one without adverse consequence? And how does age play into that? in other words, does the 5 year rule expire when you reach a certain age (59 1/2 or something else)?

Thanks

Bob,

This should answer your questions:

https://www.kitces.com/blog/understanding-the-two-5-year-rules-for-roth-ira-contributions-and-conversions/

Mike

https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/ira-faqs-recharacterization-of-ira-contributions says, “Effective January 1, 2018, pursuant to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (Pub. L. No. 115-97), a conversion from a traditional IRA, SEP or SIMPLE to a Roth IRA cannot be recharacterized.”

Does that mean Roth recharacterization rules no longer make it feasible to precisely fill the bottom tax brackets?

It would be much harder to do it precisely. If you can predict your income fairly well, you might be able to get close though. The key now will be convert enough to get close, but not enough to go over.