Executive Summary

As a guaranteed income stream that cannot otherwise be liquidated or reinvested, most retirees don’t think of their Social Security benefits as an asset. Nonetheless, its value actually can be calculated, given known payments and reasonable assumptions regarding interest/growth rates and life expectancy.

And in fact, the payments are significant enough that it would take several hundred thousand dollars just to replicate the average Social Security retirement benefit for an average life expectancy. For many retirees, that would be a material portion of their total net worth, it not the largest asset on their balance sheet!

Yet unlike most other assets, the value of Social Security is uniquely impacted by its assumptions… where unlike traditional assets, the value is actually higher when inflation rises, and is greater when interest rates are low. As a result, viewing Social Security as an asset actually reveals that it is a highly desirable asset for a retiree, uniquely capable of hedging many risks in retirement that traditional portfolios cannot… and making it all the more appealing to preserve the Social Security “asset” for its diversification by delaying benefits as long as possible!

Estimating The Lump Sum Value Of Social Security

Social Security is a guaranteed income stream available at retirement for those who qualify. Of course, any stream of income has an economic value to it; however, because Social Security is available only as a guaranteed income stream, with specified payments based on wages earned and a fixed starting date that can only be adjusted forwards or back by a couple of years, most people think of Social Security separately from the rest of their (other) assets. A portfolio is a portfolio, and guaranteed income is guaranteed income, and never the twain shall meet.

Nonetheless, the availability of Social Security is of material value to most retirees, and decisions about the timing of when and how to use Social Security can impact the needs for drawing on other assets for retirement income. And in point of fact, it’s actually relatively straightforward to estimate what the approximate value of Social Security would be as an asset on the balance sheet.

After all, Social Security’s expected payments have an anticipated time horizon – the retiree’s life expectancy – and as a payment backed by the Federal government, has approximately comparable risk to any other government bond. And once you’ve determined the payment stream, a time horizon, and a growth/discount rate, you can calculate a “present value” of the series of cash flows as though it were a lump sum asset.

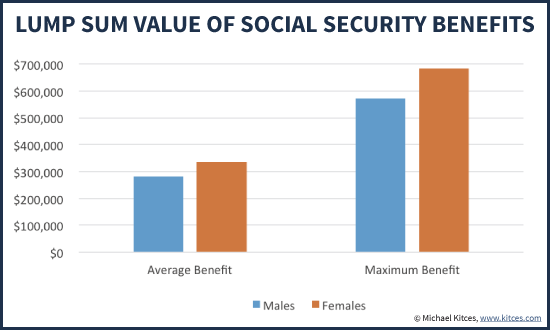

Accordingly, given an average Social Security retirement benefit of $1,294/month (in 2014), a 10-year Treasury rate hovering somewhere around 2% (at the time of this writing), assumed inflation of 3%, and a life expectancy (according to Social Security’s own 2010 Period Life Table) for someone who’s already reached age 66 (full retirement age for today’s retirees) of approximately 17 years for a male and 20 years for a female, the average “lump sum” value of Social Security is about $280,000 for males and $335,000 for females. At a maximum Social Security benefit of $2,642/month (for those who maxxed out the Social Security wage base for 35 years), the value of Social Security amounts to about $572,000 for men and $683,000 for women!

Notably, to the extent that inflation is higher than 3%, the (nominal) value of Social Security is even higher, since its future payments are all inflation adjustment. In addition, since a worker’s Social Security earnings record fuels not only his/her own benefit but also spousal payments, the lump sum value of Social Security can be as much as 50% higher for some members of a couple. Similarly, to the extent that a worker’s benefit also supports a spouse’s survivor benefit, the estimated value would be approximately 15%-30% higher, given that the joint life expectancy of a couple is longer than either males or females individually. And notably, the value of Social Security would tend to be higher for financial planning clients as well, as their affluence would tend to give them greater life expectancy than the average of the whole general population included in the Social Security period life tables.

The Impact Of Delaying Social Security On Its Lump Sum Value

While Social Security’s lump sum value can be calculated based on the full retirement benefit, the reality is that Social Security doesn’t have to be taken at that full retirement age. It can be started early at a reduced value, or delayed later for a greater payment.

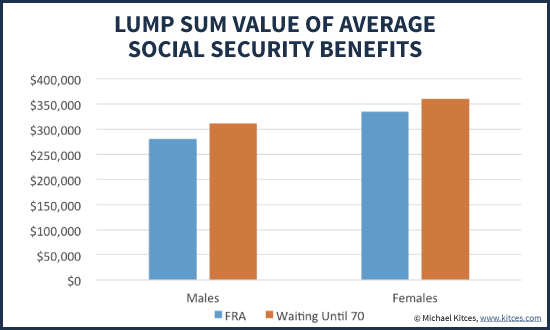

The opportunity to delay is often characterized as a “return” for delaying; after all, for each year that benefits are delayed past full retirement age, there is an 8% “delayed retirement credit” applied to increase benefits that are started later. For someone whose full retirement age was 66, waiting until age 70 results in a 4 x 8% = 32% benefit increase.

However, the caveat of delaying benefits is that while the payments will be higher, fewer are expected to be received, since the waiting retiree will be 4 years older by then and have a shorter life expectancy from that point forward. Thus, while the average benefit of $1,294/month would grow to $1,708/month by waiting until age 70 (and would actually be about $1,922/month in nominal dollars at that time, as four years’ worth of inflation adjustments accumulate as well), the payments would only be expected to last for about 14 years for a male and 16 years for a female at that point. When the value of Social Security is adjusted for the higher payments but shorter time period, and the “time value of money” for waiting four years, the lump sum value is only about $312,000 for males and $360,000 for females, a relatively modest increase of about 11% and 8%, respectively, from the benefits at full retirement age.

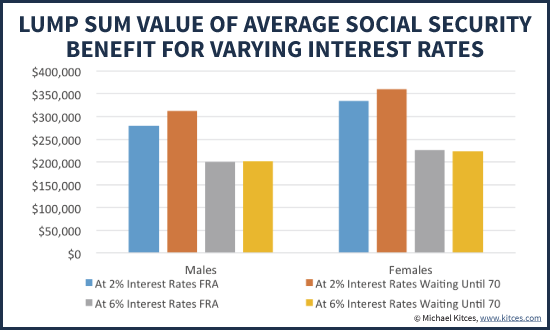

While this does still reflect an increase in the value of Social Security for delaying 4 years, it’s nowhere near a 32% increase in the asset value! And in reality, these differences are actually driven primarily by the fact that interest rates are so low, which creates a “bias” in favor of delaying Social Security (as it implicitly assumes the funds weren’t going to grow very much, anyway). In a more “normal” interest rate environment, where a government bond yields 6% instead, the value of Social Security at full retirement age versus delaying until age 70 is shown below.

As the chart reveals, when interest rate assumptions are higher, the difference between taking benefits at full retirement age versus delaying until age 70 disappears almost entirely; the benefits are lower, and nearly identical. In point of fact, this is not just a coincidence; in reality, the whole point of assigning delayed retirement credits for those who wait on Social Security was not actually to enrich them, but simply to ensure the benefits would be “actuarially equivalent” regardless of whether benefits were taken earlier or later. It is only in today’s unusually low interest rate environment that the system tilts further in favor of delaying (and in turn is tilted further in favor of delaying for those who have benefited the most from improvements in life expectancy over the past several decades).

Coordinating The Value Of Social Security With Other Retirement Assets

Notably, the factors that drive the value of Social Security also have an impact on the other assets in the retirement portfolio. As shown earlier, at higher interest rates, the asset value of Social Security is actually lower (it’s not worth as much because it wouldn’t require as much in assets to produce the same stream of payments at higher growth rates); however, when returns are higher, the value of the rest of the retirement portfolio may be greater! In other words, Social Security provides a unique form of asset to hedge against the rest of the portfolio, because it’s an asset whose value increases as returns decrease!

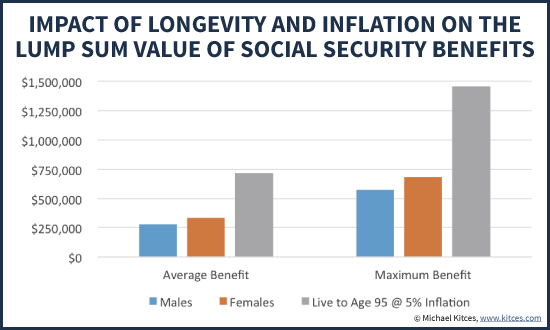

Similarly, while the value of Social Security has been calculated here based on average life expectancy and average inflation assumptions, the reality is that the value of Social Security will increase further for those who live beyond life expectancy, and will rise substantially if inflation turns out to be higher (since the payments are inflation-adjusted). For instance, if you live to age 95 and inflation turns out to be 5% instead of 3%, the value of an “average” Social Security benefit is actually a whopping $717,000 (and the maximum Social Security benefit is worth $1.46M!)!

Accordingly, then, when viewed from the balance sheet perspective, Social Security is not only a highly valuable asset overall, but one with very unique investment characteristics; unlike most other assets, its value rises in low-return environments, and is further enhanced by unexpected inflation. In addition, Social Security’s asset value naturally rises the longer you live, effectively providing a self-renewing asset that cannot be outlived (unlike the other retirement assets on the personal balance sheet!). In other words, one of the primary reasons to delay Social Security and spend other assets first is that the Social Security asset is the one best hedged to the risks that damage most retirements!

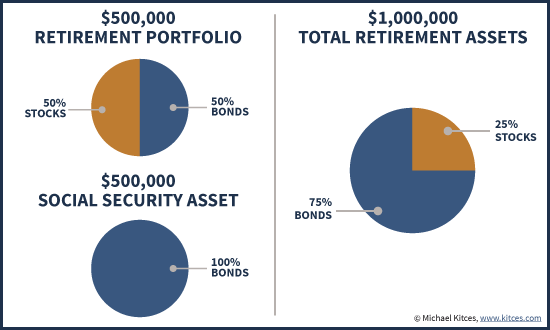

One notable caveat, though, is that the inclusion of Social Security on the personal balance sheet can actually lead to a materially “distorted” asset allocation, given that most would characterize Social Security as the asset-class equivalent of a government bond (or more accurately a TIPS bond given its inflation characteristics). After all, for most households that enter retirement with relatively modest retirement savings, an asset worth about $300,000 (for the average benefit) might be equivalent to the size of their retirement portfolio! A more affluent household that saves $500,000 for retirement – and has higher Social Security benefits also worth about $500,000 – may still find Social Security comprising about 50% of the total retirement assets. Yet if this household has $1,000,000 of total retirement assets, including a “balanced” 50/50 portfolio and a Social Security “bond” asset, then their true asset allocation is not 50/50, but 25/75!

Unfortunately, though, the fact that the Social Security “asset” biases the household balance sheet towards bond holdings is difficult to fix. After all, given that Social Security isn’t actually a liquid asset to be invested/allocated – or even seen as an account balance – getting to a 50/50 total mix would actually require putting 100% of retirement portfolios into equities! While this may be justified from a total household net worth basis, it would clearly be difficult to implement in practice, where clients may fixate on the equity-only portfolio and its volatility, and not necessarily recognize the role that the Social Security “bond” asset is playing to diversify it!

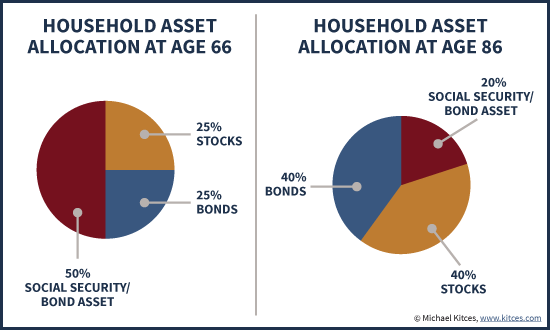

Ironically, though, as most retirees tend to rely on Social Security payments first (at least once they begin) and allow the portfolio to grow to the extent possible, the distortion of the household balance sheet towards a bond-heavy allocation actually resolves itself over time. As the years go by, the remaining value of the Social Security asset depletes (as it self-liquidates with payments), while the retirement portfolio tends to grow (especially in the first half of retirement when withdrawals are still modest); accordingly, the equity allocation of the household balance sheet actually glides higher on its own throughout retirement (as the equities in the portfolio comprise a larger percentage of total wealth) even if the portfolio itself remains 50/50 in stocks and bonds.

The bottom line, though, is simply to recognize that while it may not be a “liquid” asset or one that is naturally valued, Social Security is actually a very material retirement asset for most, and one with very unique investment characteristics that form a natural hedge for the rest of a retiree’s portfolio. Accordingly, while it may be difficult to actually adjust a household’s overall asset allocation around the bond-like Social Security asset, spending and liquidation decisions – including when to tap Social Security versus other portfolio assets – should be done in recognition of the fact that the Social Security asset may actually be better hedged than a traditional portfolio against the risks that endanger a retirement!

So what do you think? Have you ever included the present value of Social Security benefits as an asset on the client’s balance sheet? Would doing so make it easier to have the conversation about when/whether it’s best to delay Social Security benefits? Does this provide you with a different perspective on how to think about the value of Social Security?