Executive Summary

Good diversification is a staple of financial planning advice, though the principle long pre-dates financial planners. From the aphorism “don’t put all your eggs in one basket”, to Talmudic texts from 3,000 years ago directing people to split their wealth evenly between cash, real estate, and business, the virtue of limiting exposure to risk from diversification is an “accepted truth”.

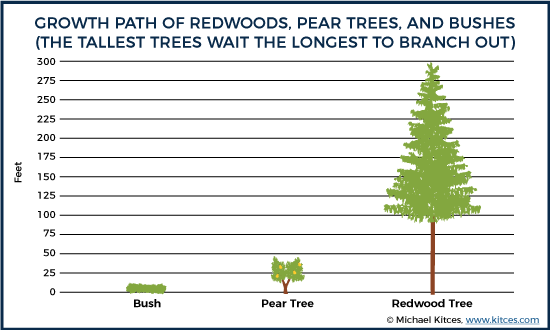

Except the reality is that, when you look to those who achieve the greatest wealth or have the greatest impact, virtually none of them ever diversify… or at least, not throughout most of their years. After all, if Bill Gates had “just” diversified into the S&P 500 after Microsoft IPO’ed, he’d have barely 1/40th of the wealth he does today. In fact, most of those on the list of the richest billionaires are people in their 60s, 70s, or 80s, who have held a concentrated interest in their businesses for nearly their entire lives. Like the redwood tree, they waited a very, very long time before branching out… and as a result, were able to grow the tallest.

Of course, that doesn’t mean that diversification is always bad. Most “trees” are actually short bushes and shrubs, that grow just a few feet tall, but are still able to broaden their shoots and leaves enough to grow healthy. In the investing context, it’s the equivalent of a person who diligently saves and invests in a portfolio for decades, and retires with “comfortable wealth”.

Still, it’s important to recognize that diversification isn’t literally always the winning strategy, and for those who are young and have a long time horizon, arguably not even a necessary one. In fact, the weakest tree is the Bradford Pear – known for growing a V-shaped trunk, effectively diversifying itself from the start… in a manner that virtually ensures the tree will eventually either collapse under its own weight, or succumb to external forces.

For those who have decided they have “enough”, the satisficing strategy of the bush may be just fine. But for those who decidedly want to generate more wealth or have more impact, perhaps the redwood strategy is underrated after all? In fact, the highest-risk losing strategy may actually be the pear tree strategy of trying to have it both ways at once!

Redwoods, Pear Trees, and Bushes

Image source: http://maxpixel.freegreatpicture.com/Forest-Landscape-Trees-California-Sequoia-79761

The tallest trees in the world are Redwood Sequoia trees, with a typical height of more than 300 feet. New redwood sprouts can grow as much as 7.5 feet in a single growing season, although ultimately the oldest ones are estimated to have been around for 1,200+ years. The tallest known redwood, dubbed “Hyperion”, is a whopping 379 feet tall, and is believed to be more than 600 years old. And most mature redwoods extend so high that there aren’t even any branches on the tree for the first 100+ feet up the trunk.

By contrast, bushes have with multiple stems and branches that spread out from the base. And as a result, they tend not to be very tall, with most bushes no more than a few feet high, and even “tall” bushes typically don’t grow more than 10-20 feet high. Though they usually don’t need to be very tall, either, as the breadth of leaves at the base of a bush is more than enough to gather the necessary sunlight for photosynthesis.

Image source: http://maxpixel.freegreatpicture.com/Trees-Nature-Blatter-Bush-Periwinkle-Green-Plant-217546

In point of fact, recent research suggests that bushes tend not to grow as tall precisely because they don’t have to. They engage in a satisficing strategy of being just tall enough and broad enough to get the sunlight they need. It’s only the trees that grow tall, in part because once the tree grows narrow and high, it can only succeed and gain the sunlight it needs by outgrowing the other trees around it. Yet doing so means it’s absolutely essential that the tree establishes strong roots and a solid trunk, or it can’t grow tall enough to survive and thrive for long.

Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3A2014-11-02_14_11_35_Bradford_Pear_during_autumn_along_Hunters_Ridge_Drive_in_Hopewell_Township%2C_New_Jersey.jpg

Accordingly, the oldest and tallest trees are generally the ones that wait the longest and grow the tallest before branching out, while those that branch out early are much shorter. Fruit trees, which tend to have a wide span of branches just 10-20 feet off the ground, typically only live for 35-45 years, and the Bradford Pear tree is well known to be one of the shortest-lived trees (at 15-25 years) because of its tendency to have a V-shaped trunk from its base – which means it’s only a matter of time before it grows to the point that it splits under its own weight, or alternatively is destroyed when a major storm comes through that its fragile branch split cannot withstand.

Of course, ultimately branching out, so a tree can grow the breadth of leaves necessary to gather sunlight, is crucial. Even the giant redwood eventually branches out. Although the most mature redwoods have no branches for the first 100+ feet of the tree trunk! Nonetheless, the point remains that the tallest trees are the ones that tend to wait the longest to branch out, and the earlier and broader a tree (or bush) branches, the less likely it is to grow as high or survive as long.

The Bush Strategy To Saving For Retirement

In the world of investing, most people save and accumulate for retirement like a bush (or at least, that’s what we advise them as financial advisors). Each bit of savings is allocated into a diversified portfolio, which like a bush with a lot of stems and branches, allows us to grow and bulk up over time.

After all, diligently saving “just” about $300/month in a diversified portfolio growing at 8% for 40 years is sufficient to grow a $1,000,000 portfolio (at least before taxes). Someone who is able to max out their entre $18,000/year 401(k) contribution for 40 years can accumulate a whopping $4.6 million in retirement savings.

However, as with the limitations of the bush itself, that’s about “as good as it gets” when saving for retirement like a bush. And most people won’t even be this successful, as the average American doesn’t have enough “excess” income to max out 401(k) contributions, at least not every year for 40 years, when you also have to navigate getting married, buying a house, starting a family, child care, college funding, etc. Not to mention that very few are able to earn enough to maximize their 401(k) contribution limit on top of even basic living expenses in the early career years.

Fortunately, having a $1M+ portfolio is still more than enough for most people to retire and live a comfortable live, and most retirees make due with even less (especially when supplemented by Social Security benefits).

Still, it’s important to recognize the limits of the bush strategy. You’ll likely never meet a Bush saver with more than $5M of net worth, unless he/she had an extraordinarily high income to save in the first place. And you’ll certainly never find someone with $10M who achieved it as a Bush. To do that, you have to be a redwood.

The Redwood Strategy To Building Substantial Wealth

One of the most interesting commonalities of the world’s richest people is that virtually all of them achieved their wealth by not diversifying for most of their lives. From Bill Gates’ shares in Microsoft to Jeff Bezos’ Amazon stock, Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook shares, Larry Page and Sergey Brin’s Google, and the Wal-Mart shares of the Walton family… no one on the Forbes list of billionaires got there by diligently saving into a diversified portfolio. Instead, like the redwood, they stayed concentrated and focused in a single direction for a very long time. And in point of fact, for most of them, their primary wealth asset is still their company stock.

Nor is this phenomenon new. The first person to ever reach a nominal net worth of $1 billion was John D. Rockefeller, which at the time was a mind-number 2% of national GDP… and came almost entirely from the wealth of his company, Standard Oil! Similarly, Andrew Carnegie made his money from the Carnegie Steel Company, Henry Ford from Ford Motor, the Vanderbilt’s family wealth came from the family railroad and shipping business, and the bank that created J.P. Morgan’s wealth still bears his name.

Of course, as noted earlier, most people can accumulate more than enough wealth to satisfy their basic personal needs and retirement goals by simply saving and investing in a diversified manner like a bush, and not pursuing the redwood strategy of holding and compounding the growth of concentrated wealth. Nonetheless, the fact remains that entire orders of wealth magnitude are only effectively available to those who don’t diversify like the bush, and instead stay focused (and concentrated) like the redwood that reaches for the sky.

Plant Lots Of Seeds But Don’t Split Your Trunk By Diversifying Too Early

A crucial caveat of the redwood strategy is recognizing that most redwoods don’t actually make it. Researchers have estimated that seed viability of redwoods may be as low as 3%, and similarly there are estimates that as many as 90% of entrepreneurial startups end out failing. It is perhaps no great surprise – if the redwood strategy were easy, everyone would do it, and then no redwoods would stand out because all the trees would be that tall! But still, that means it’s risky to try to be a redwood. There’s a reason why bushes and shrubs are more viable in so many parts of the world.

Still, as noted earlier, the weakest tree is not the bush or the redwood, but the Bradford Pear – a tree that tries to grow tall like a tree, but branches out too early, inevitably collapsing under its own over-diversified weight. In other words, if you’re going to be a bush, be a bush, and if you’re going to be a redwood, be a redwood. The worst strategy is to try to grow like a redwood, but diversify like a bush… because you end up like a pear tree.

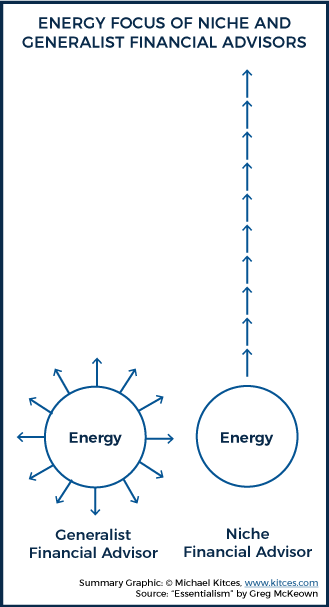

And arguably, a similar effect occurs in the growth of one’s personal career. The point, as made by Greg McKeown in Essentialism, is that focusing your energy in a limited number of directions can compound far greater results than spreading our energies in lots of directions at once. While it may feel “safer” to not put all of one’s eggs in a single basket, the challenge remains spreading one’s resources too thin too early just limits personal success.

Again, the tallest trees are the ones that wait the longest to branch out, as the Bradford Pear that splits its trunk early to “diversify” its opportunities just ends out splitting apart later, or quickly succumbing to external pressures because it lacks the solid core necessary to withstand natural forces.

Again, the tallest trees are the ones that wait the longest to branch out, as the Bradford Pear that splits its trunk early to “diversify” its opportunities just ends out splitting apart later, or quickly succumbing to external pressures because it lacks the solid core necessary to withstand natural forces.

Plant Redwoods When You’re Young, Grow Bushes When You’re Older

The fundamental point is that, while diversification is commonly lauded – for many good reasons – it has trade-offs worth considering. While having “too much” concentration of wealth can leave one exposed to greater risks, it’s also the path to greatest rewards. Diversification may preserve great wealth or impact, but seldom creates it.

Of course, growing the tallest trees also just takes time. It’s no coincidence that most of the world’s wealthiest billionaires are in their 60s, 70s, and 80s. Compounding takes a while.

Accordingly, it is arguably best to pursue Redwood strategies when you’re young. Not only because it allows for the longest time to grow and compound – if it works out well – but also because it allows time for alternatives if the concentrated redwood strategy doesn’t work out. In other words, if you plant a bunch of redwood seeds in your 20s and 30s, and none of them sprout, you still have time to plant some (diversified) bushes during the empty-nest phase in your 40s and 50s.

At the same time, though, what this analogy suggests is that there is such thing as diversifying too soon and too quickly. Whether it’s trying to build multiple income streams instead of focusing on one business, or trying to diversify wealth instead of allowing a closely held business to compound, the risk-minimizing nature of diversification is also a limiter of success, too. For many, that may be an acceptable trade-off – particularly if some level of success or affluence has already been achieved. But maybe it’s not such a bad idea for 20-somethings with a lot of wealth concentrated in company stock and options to just keep holding onto them and hoping it grows much, much bigger. The fact remains that the tallest trees are the ones that grow the highest before they branch out!

Or stated more simply, you can have a good life as a bush, but true wealth comes from being a redwood. Yet trying to split the difference and diversifying too early – acting like a pear tree – may be the strategy most likely to catastrophically fail!

So what do you think? Is the analogy of redwoods, bushes, and pear trees reasonable? Should investors be cautious about not diversifying too early? As advisors do we have a bias towards diversifying towards bushes and discouraging redwood entrepreneurialism? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

I think the “redwood” strategy applies almost exclusively to equity holders in high-growth businesses, especially ones who have significant voting rights and can therefore influence strategy. I have trouble thinking of a situation in which I’d be comfortable suggesting to a client who is investing their retirement savings in financial assets, that it would be smart to delay diversification. Investors are prone to overconfidence and magical thinking. Encouraging them to behave as if they had materially above-average skill in allocating capital will mostly lead to bad results. Maybe they are holding the next Amazon, or maybe it’s just the next Webvan.

Ben,

I think that’s a fair point about limiting scope. Or at least, there’s an additional layer involved when the shareholder can ACTUALLY influence the path of the company (e.g., closely-held business), as opposed to “just” riding along with a closely held position in a publicly traded stock (e.g., average person’s life savings in Amazon is still less than a 0.01% ownership position).

Arguably, that also makes sense, in that a smaller (relative-size) closely held business is also riskier, and therefore should be able to command a higher risk premium than the general market of publicly traded stocks? (Obvious caveat that not all risks are necessarily rewarded, though!)

– Michael

I think the analogy is well suited for financial planning companies, in terms of the importance of working a niche. The idea of being a jack of all trades in finance or a true professional and expert in a limited number of areas. I think the “holistic” financial adviser can turn into the unintended peddler of inadequate rules of thumb. Focus on the niche, until you stand tall above the rest!

I think the analogy is well suited for financial planning companies, in terms of the importance of working a niche. The idea of being a jack of all trades in finance or a true professional and expert in a limited number of areas. I think the “holistic” financial adviser can turn into the unintended peddler of inadequate rules of thumb. Focus on the niche, until you stand tall above the rest!

Mark,

Indeed, I think firms like Hanson McClain (see https://www.kitces.com/blog/scott-hanson-mcclain-retirement-network-podcast-niche-radio-show-money-matters-parthenon-capital/) are a good example of this as well.

Deep niche for a long time. Went broader in their later years. But only AFTER the first billion or two of AUM… and it was the business base they built IN the niche that gave them the resources to go broader…

– Michael

Focusing your investments increases the variability of possible returns. We probably all know individuals who temporarily became multi-millionaires investing in WorldCom or Enron or had their stock options expire worthless. Anyone following a “focus” strategy should have a high tolerance for uncertain outcomes and follow Will Roger’s advice “If it doesn’t go up don’t buy it”

“Diversification is a hedge for ignorance. By being very selective, you increase your chance of picking superior performers.”

William O’Neil “Market Wizards”

The reason for diversifying is less about maximizing returns than it is about minimizing risks.

Think of the Big Winner in a casino crap game. He probably made a high-odds bet (boxcars), won on the first roll and then let it ride. This is a great strategy when it works (like it did for Bill Gates), but the usual outcome is to lose everything you bet.

As always, the right investment strategy is a function of your goals: Some people want to win big or go home. Others see the casino as an entertainment venue, and if they can make their money last” for a few hours, they go happy, even if they leave with little in their pockets.

Fair point, but not everyone wants to be a risk-minimizer. And arguably, some people don’t necessarily need to be (e.g., young person with lots of time and future job/career/business opportunities)?

As advisors, we tend to default to “always” advocating for risk minimization. The goal here was to show at least some perspective on the alternative view?

– Michael

‘risk minimiser’ – if the objective is maximise efficient growth over (say) a 25 year pension accumulation period, then by diversifying away from equities for the first (say) 15 years of that time is creating the risk that pension funds will be insufficient. It’s odd that the superior returns of equity are ignored as soon as someone says ‘portfolio’.

i suspect that in the US, just like here in the UK, there is a very long overdue redefinition of the term risk as it applies to the individual retail investor, and folk should stop using the frame of reference that came from the institutional side.

Risk to a person for their pension is that the investment does not have the right return, producing the right income at the right time, it’s not about standard deviation.

To “flog” perhaps the tree metaphor a bit more: the mature redwood scatters a multitude of seeds, but only a vanishing small number germinate and develop into viable young trees. To place things in a more relevant financial context, I’m reminded of Bessembinder’s recent article describing his comprehensive study of long-term stock returns: ” When stated in terms of lifetime dollar wealth creation, the entire gain in the U.S. stock

market since 1926 is attributable to the best-performing four percent of listed stocks. These

results highlight the important role of positive skewness in the cross-sectional distribution of

stock returns.” The young redwood seed it appears, has an ~ 1/25 chance of seeing daylight through a focused portfolio..

Just so we’re clear, by diversification are we distinguishing between asset allocation across asset classes and diversifying within a single asset class?

I think there are billionaires who early on diversified within an investment class even while they allocated almost all assets to a single class. I believe Warren Buffet pursued that strategy. I don’t think contrarian investor Carl Icahn put all his eggs in one basket early on, so he was diversified. But he did confine his investments to more risky classes.

IMO, the most wealth limiting strategy pursued by many investors is allocating a significant portion off assets into low risk, low return classes early in life. What I’m meaning is that far more wealth in total is foregone by:

a) investing in riskless assets at age 25;

than by

b) diversifying within the equity class of assets.

I would think financial advisors might better be able to sell a diversified portfolio of redwood,

oak, pecan, and cherry trees than a portfolio of just redwoods. Further, I think an advisor might be able to show that investing in that portfolio will better provide for long term needs than investing in onions, blackberries, and daisies.

It sounds as if you are suggesting that younger people try their hand at stock picking which feels like to me a “win big, lose big” idea. IMHO there are too many empirical studies that show the graveyards to be full of stock pickers. Isn’t diversification a more prudent path to wealth creation for young investors as well? As far as your metaphor goes with tree’s I like it. I agree that most people with larger sums of wealth made a bet on a company, but it was THEIR company that they built which was also their income stream. I’m having a hard time reconciling the idea that younger people should try stock picking if that is what you are saying. Thanks in advance for your reply. I love reading your posts and your thought leadership is 2nd to none in my opinion.

Daniel,

I’m not sure I’d advocate for individual stock picking, as most young people also just don’t have the training/education to even be capable.

But it does mean that when they get opportunities to participate in company stock, stock options, etc., that it might be worthwhile to encourage them to invest more and keep it as long as they can?

– Michael

This brings to mind Ashvin Chhabra’s book The Aspirational Investor. He makes a similar suggestion. Divide into three buckets: safety, core, Aspirational.

Concentrating assets [a Warren Buffett investment principle] only works if you “know what you are doing”. And when you are young, it is less likely that you know what you are doing.

As several other people in the comments have touched upon, it is less risky to diversify when young, study and hone your investment skills, and then concentrate your assets later. The pear tree analogy is not very appropo. While the pear tree is locked in forever to its early branching (diversification), people can always change their asset allocation and selection.

Of course if you are in the <1% who "know what you are doing", any diversification is dilutive. Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg made the ultimate concentration bet by each dropping out of Harvard to run their companies.

But did Bill G. and Mark Z really know what they were doing? They didn’t and would never tell you they did. But they succeeded. And many, many other sequoia “attempts” failed.

I think young people should have all equities, but diversify within that class. They have plenty of time to ride out the downturns. Regarding redwoods, the success rate in that area is horrible. How many businesses fail versus those that become an Amazon or Apple? Chances of that are very slim. Diversify within asset classes, and take a flyer on some new companies if you want. You can get wealthy getting into the Facebooks, Apples and Amazons early on, and if they fail, you won’t lose everything.

Many individual businesses fail, yes! But hungry, smart, and good entrepreneurs eventually start successful businesses after several failed attempts. Maybe not billion dollar companies, but they could be worth millions or hundreds of thousands. i.e. One can still make more money than working for an employer by being an entrepreneur. Unless said entrepreneur is not self aware enough to know what they’re good at and what they stink at.

None of the Redwood’s listed in the article “invested” in these companies, they built them. Maybe your article should be read as career advice. Bushes get normal jobs and diversify investments. Sequoia’s take real risk, almost never lose focus and if they make it, may achieve phenomenal growth. The least long lived career is a Pear tree trying to do both – work a job and launch a sequoia, ultimately doing neither particularly well.

Christian,

Fair point. This is a new thought journey to me, and I think it’s reasonable to consider whether/where it should be narrowed.

As you may note, the later section did begin to apply this in business context (finding focus in your career/firm before branching out). I’ll ponder whether that could be expanded upon further. I may need a new analogy (or at least new examples) though… 🙂

– Michael

Christian – I strongly agree with your reframing! THIS is exactly what I was as thinking. I’ve read a lot about concentrating wealth in the past 1-2 years. And the best concentrating bet you can make is on yourself/career. Since you can control your effort. i.e. start a business and invest in it. Obviously start ups come to mind, but I also know some rich people who own family cleaning, construction, and lawn care businesses. Very few people get mega rich working for someone else. Bankers, lawyers, doctors grind it out. But they’re not billionaires. Now…on to creating a career/business plan!

Another aphorism – keep all your eggs in one basket, and watch the basket closely. The best ROI one can achieve is nearly always one’s own business, which makes sense given the risk/reward. In one sense, diversification (financial assets outside of closely held business) is protective. Sufficient capital to weather downturns or to exploit growth opportunities are major risk factors for closely held businesses. Timing of capital allocations is similar, but not the same as diversification. For retail investors, attempting to take concentrated positions in enterprises in which they don’t have a controlling interest adds risk without sufficient rewards.

Cannot be enough discussion on asset allocation. A 1986 study found that asset allocation accounted for 94% of the differences in total returns achieved by institutionally managed pension funds Cash and Allocation is King.

This resonates most in connection with advising entrepreneurs. Especially in the context of how much to invest in their businesses vs. how much to put away (as a hedge) in a diversified portfolio as they grow their businesses. And it’s so idiosyncratic; depending on what kind of business they are in. What the capital requirements are. What kind of exit might be in store, and when.

Great article, a few thoughts come to mind.

• While those outliers did do way better by concentrating their holdings, the probability for this to happen is still very low. How many IPOs outperform the market in the long run?

• I don’t think the right question is if Bill Gates would have invested all his shares in the S&P 500 instead of MSFT. The question is if he would have taken some of his stock and diversified it,(maybe he did, for the past 20 years he for sure did.) how much upside did he give up vs. the downside he would have protected.

Thoughtful article Michael. I do like the analogy regarding the different types of trees and reference to Essentialism. Although I would echo others here as far as the articles application being primarily for business owners and those who can obtain company stock, participate / influence its growth and hold it a long time. However, I’d be interested to know if you have additional thoughts about the application of these principals to single asset class selection for individual investor wealth building over multiple decades? I know this could be a risky question to answer from a compliance perspective so no problem if you prefer not to comment. Thanks!

You make a good point about not likely being able to max out 401k over your whole career. I think moving away from annual contribution limits on retirement accounts to lifetime contribution limits would make more sense. That would allow people to play catch-up better as their earnings increase and they can afford more than the current max while also allowing short term high earners like professional athletes to put lots of money away while they have the extra cash flow during their playing years.

Dude awesome post! Seriously. And redwoods are amazing. We live in Northern Cali and I am often hiking amongst them. Very cool. Could not agree more. Niche is key to early and sustained growth. Then diversify once rich, the problem with stocks is that it’s hard to pick a niche unless you are in it.

For the non stock option employee, with “just” paycheck to paycheck savings, it’s about finding the “right” business(‘) or sector(s). From 1980 to today that would have been technology.

The “next” big thing, that could run 20-30 years, will be “clean tech”. Be it air, electricity, cars, or water. The redwood grows tall because it can, and it needs sustained time, i.e. a business or a sector that can and does grow for an extended period of time.

Easy concepts to articulate, hard businesses and sectors to identify.

Then there is multi-generation life insurance. Insure grandpa instead of your 401k- tax free death benefits anybody?