Executive Summary

While it may be easy to assume that having more money would make a person happier by opening consumption opportunities unavailable to those with less income, experienced advisors can likely identify many examples of high-income individuals who are unhappy with their lives. To provide a more holistic view, researchers have sought to assess whether increased income leads to greater happiness on two dimensions: emotional wellbeing (how an individual feels today) and evaluative wellbeing (how an individual feels about their life overall).

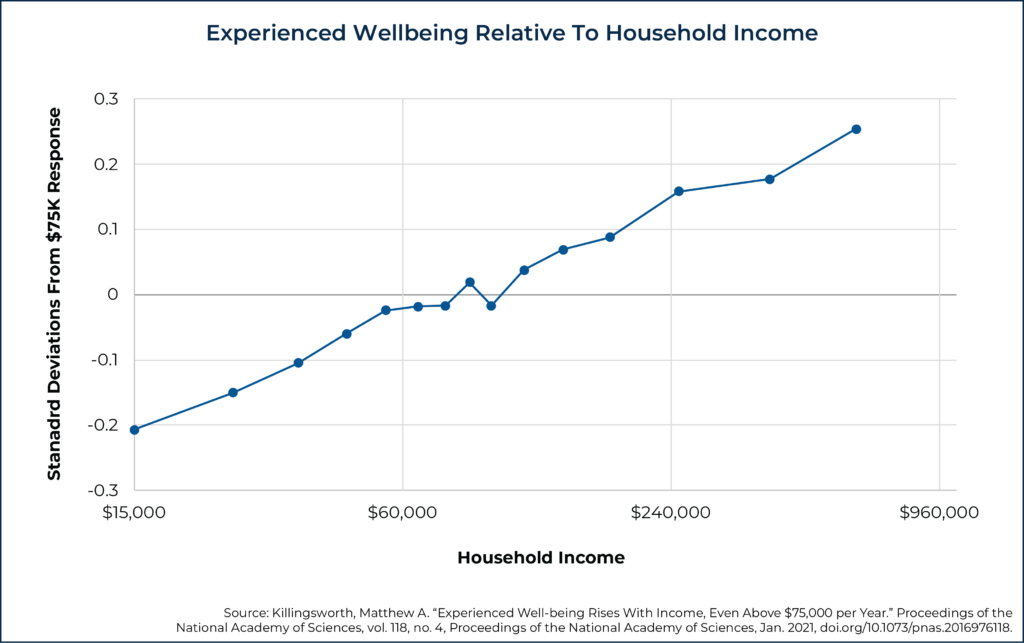

An oft-cited 2010 study by Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton found that while overall life evaluation was positively correlated with income (even at levels exceeding $120,000), emotional wellbeing only increased up to $75,000 of income, plateauing after that point. This suggested that, after a certain point, increased income would not necessarily increase an individual’s day-to-day happiness. However, a 2021 study by Matthew Killingsworth using a more granular measurement scale found that day-to-day wellbeing continues to increase even beyond income levels exceeding $75,000 (while also finding that overall life evaluation increases with higher income as well).

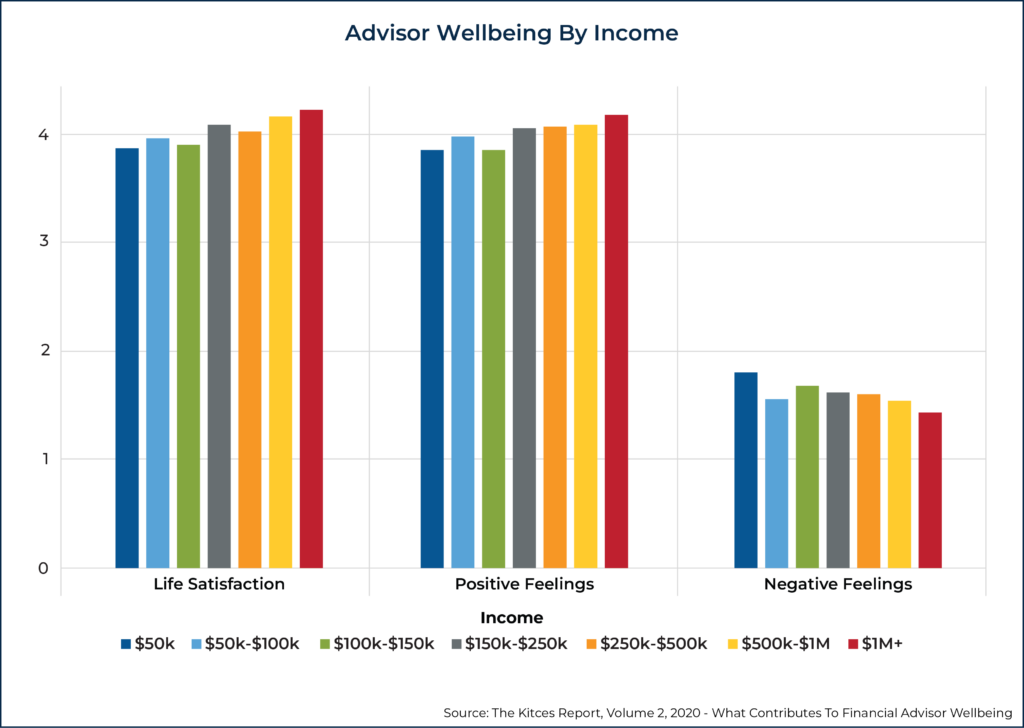

When it comes to financial advisors, in particular, Kitces Research found a similar positive correlation between income and happiness. For instance, our research found that not only is advisor take-home income positively correlated with overall life satisfaction, but also that, similar to Killingsworth’s findings, their income is positively correlated with positive feelings and negatively correlated with negative feelings, even as income exceeds $75,000.

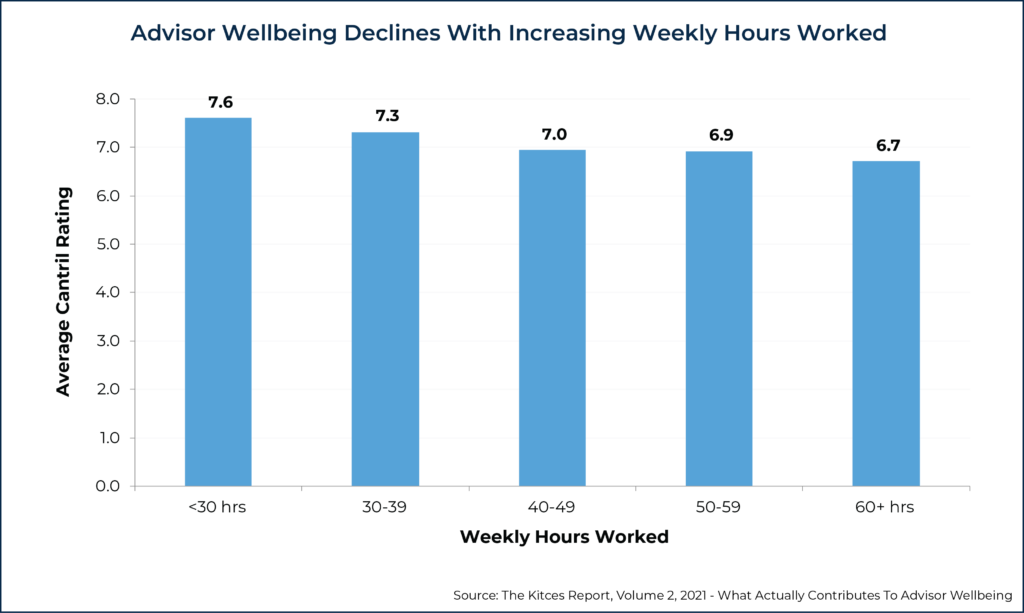

Importantly, there are other factors that can mediate the relationship between income and happiness, which may explain why higher income doesn’t always lead to greater happiness. For instance, Killingsworth found that respondents increasingly reported that they did not have enough time to get things done as their income rose, serving as a small but significantly negative mediator of the association between income and experienced wellbeing. This concept of ‘time poverty’ also appears to apply to financial advisors, as Kitces Research has found that the number of hours an advisor works in a given week is inversely correlated with their wellbeing.

These findings suggest that advisors who choose to pursue increased income in the pursuit of greater experienced happiness may be more successful if they deliberately protect the time they have available for their other responsibilities and interests. A few ways that can help advisors do this include adding staff as their firm reaches certain revenue ‘pain points’ where they have too much work on their plate, and allocating more ‘hard dollars’ paid to outside vendors for marketing services as the firm grows, allowing firm owners to use their time for more valuable and/or enjoyable activities.

Ultimately, the key point is that as an advisor’s income increases, their wellbeing – in terms of both day-to-day happiness and overall life evaluation – can potentially increase as well. But if higher income comes with increased demands on the advisor’s time, particularly if they get to the point where they feel they don’t have time to finish everything they need to get done, the experienced ‘time poverty’ can have a negative effect on the advisor’s wellbeing. In the end, time is the ultimate scarce resource, and it is important for advisors to spend it wisely, particularly as their income increases!

Is more money the key to happiness? Researchers have explored this question for years, as it has significant implications, both on a societal level and for individuals making decisions in their own lives. For instance, if happiness tends to max out at a certain level of income, then working more hours for additional income could be counterproductive for an individual. Further, because happiness can be measured on multiple levels (e.g., happiness in the moment versus overall life satisfaction), research might indicate that additional income has an effect on one level of happiness but not another.

For advisors, such findings would have implications not only for their clients (who might face decisions about working a more stressful job for additional income, or perhaps considering retiring early on a lower income), but also for themselves, as they consider working more hours in the pursuit of additional income.

Why There Might Not Be A ‘Plateau’ In The Relationship Between Income And Happiness

While the relationship between income and happiness will vary across individuals, researchers have sought to explore the question of whether income brings additional happiness only up to a certain level or whether there is a continually increasing level of happiness as income rises. This research has focused on two types of happiness: experienced happiness or emotional wellbeing, which reflects an individual’s feelings at a given moment; and life satisfaction, which indicates how an individual evaluates their life situation as a whole. And even though each individual’s circumstances are different, research on these issues can still provide valuable insight on a societal level and can help advisors consider how their clients (and themselves) are doing on each level.

Previous Happiness Research Suggested A Plateau In Emotional Wellbeing

A 2010 study by Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton sought to explore the relationship between income and happiness using survey data from the Gallup Organization. They looked at the effect of income (and other variables) on two types of happiness: emotional wellbeing (measured by asking whether the individual surveyed felt a range of positive and negative emotions the previous day) and overall life evaluation (measured by asking where respondents would place themselves on a ladder where a score of 0 represented their worst possible life and a score of 10 represented their best life).

The researchers found that overall life evaluation was positively correlated with income and continued to increase as individuals’ incomes exceeded $120,000, so that an individual with $120,000 of income would, on average, be happier with the overall course of their life than someone with $100,000 of income, who would be happier than an individual with $50,000 of income.

Notably, the link between income and happiness was based on a logarithmic increase in income, meaning, for example, that a doubling of income would result in the same increase in overall life evaluation (e.g., an individual would get the same happiness bump moving from $50,000 to $100,000 of income as they would going from $100,000 to $200,000 of income). This makes intuitive sense, as, for example, a $15,000 raise is likely to have a bigger impact on the life of someone making $30,000 (whose income would increase by 50%) than for someone making $250,000 (who would only experience a 6% income boost).

On the other hand, the researchers found that while emotional wellbeing rises on a percentage (logarithm of income) basis up to about $75,000, there is no further progress in day-to-day happiness beyond this level. One possibility for this finding is that an individual’s wellbeing may increase on a daily basis as they are able to meet more of their basic needs (e.g., live in quality housing and meet their food needs), but once their basic needs are met, other non-monetary factors, such as their temperament or life circumstances, could play a more important role than income in determining their emotional wellbeing.

More Recent Research Suggests Experienced Happiness Continues To Rise At Higher Incomes

The ‘$75,000 happiness plateau’ proposed by Kahneman and Deaton has been cited by media outlets for many years and has left many consumers wondering whether striving to earn more than $75,000 would really be worth the effort (though notably, much of the coverage of the study only highlighted the cap on emotional wellbeing, omitting the finding that overall life evaluation increased beyond $75,000 of income). However, a 2021 paper by Matthew Killingsworth sought to revisit the Kahneman/Deaton results using a newer data set.

Like Kahneman and Deaton, Killingsworth found that overall life satisfaction increased with logarithmically increasing income, and this “evaluative wellbeing” (Killingsworth’s metric equivalent to Kahneman & Deaton’s overall life satisfaction) continued to increase as individuals’ income exceeded $500,000. Where Killingsworth’s findings differed, however, was in measuring “experienced wellbeing” (i.e., people’s feelings on a day-to-day basis, roughly equivalent to Kahneman & Deaton’s measure of emotional wellbeing).

Killingsworth found that there is no income plateau for experienced wellbeing, with those making more than $75,000 experiencing (on average) more happiness than those with lower incomes, with no ‘income plateau’ where day-to-day happiness stopped increasing. Like evaluative wellbeing, these gains were assessed on a logarithmic income basis so that a given percentage change in income (rather than a change in dollar terms) led to the same degree of change in happiness.

Why were Killingsworth’s results different than those of Kahneman and Deaton? Killingsworth suggests that the data in his study were collected and measured in a way that provided a more accurate view of the respondents’ feelings at a given moment. Killingsworth used data from Track Your Happiness, a project which asks participants to report how they feel at the moment during random times of the day (whereas the data in Kahneman and Deaton’s study relied on the respondents’ recollection of how they felt the previous day).

Perhaps more importantly, those using Track Your Happiness were able to select from a range of options regarding their emotions (e.g., a continuous response scale with endpoints labeled “Very bad” and “Very good”), while the questions used in the previous study only gave respondents the option to respond "Yes" or "No" to a given measure of experienced wellbeing. The continuous response scale allows for more variation in responses across income levels.

For example, while someone making $50,000 might say they felt “Good” while another respondent making $100,000 says they feel “Very Good” (thereby showing that the higher-income individual was happier at that moment), both individuals would only have responded “Yes” when only given two options (when, in fact, their happiness did vary).

Interestingly, Killingsworth’s research also showed that the more individuals equate money and success, the lower their experienced (day-to-day) wellbeing was on average; there did not appear to be any income level at which equating money and success was associated with greater experienced wellbeing! This shows how personal attitudes can affect happiness (no matter an individual’s income), as well as the importance of setting better-defined goals (e.g., setting an income target of $150,000 rather than just wanting “more” income).

Other Research On Income And Happiness

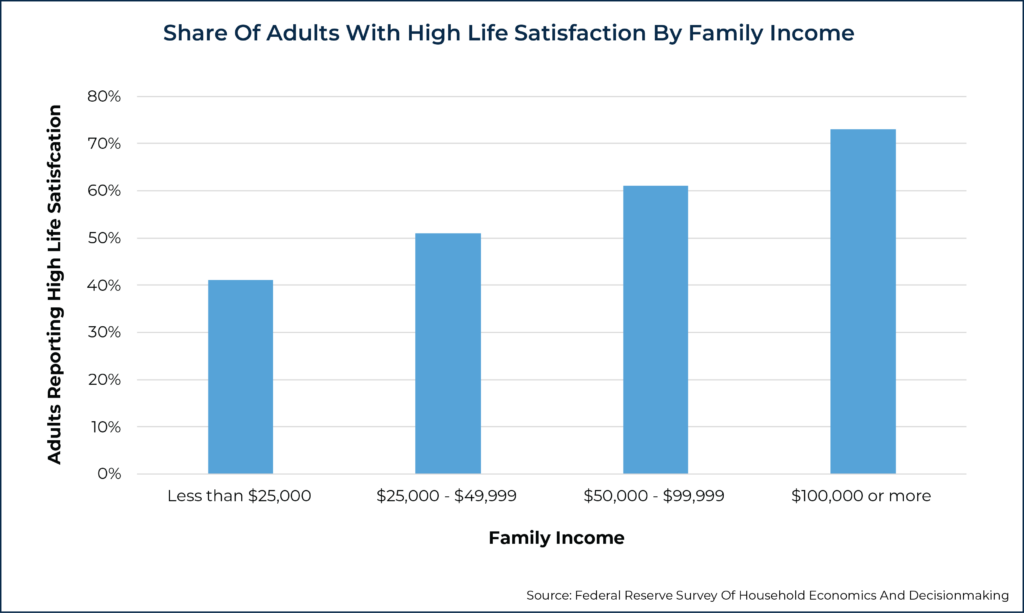

Research into the relationship between income and happiness extends beyond the academic realm as well. For example, the Federal Reserve conducts an annual Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED), which evaluates the economic wellbeing of U.S. households and identifies potential risks to their financial stability. In its 2021 survey, the Fed found that overall life evaluation (measured by asking respondents to rate how satisfied they were with life as a whole on a scale from 0 to 10) was correlated with income, with 41% of those with a family income of less than $25,000 reporting high life satisfaction and 73% of those with $100,000 or more reporting the same (in between, 51% of those with family income between $25,000 and $49,999 reported high life satisfaction and 61% of those with income between $50,000 and $99,999 said the same).

While the previously discussed research provides insight into the American population as a whole, financial advisors might wonder what the research says about advisors specifically. Notably, our own 2020 Kitces Research on “What Actually Contributes To Advisor Wellbeing” found that not only is advisor take-home income positively correlated with overall life satisfaction (as shown in the broader research), but that income was also positively correlated with positive feelings and negatively correlated with negative feelings (which reflect a similar “experienced happiness” as discussed by the authors of the previously cited research).

This means that advisors with higher incomes felt more positive feelings and fewer negative feelings than those with lower incomes, in agreement with Killingsworth’s conclusion that there is no income plateau for experienced happiness for the income range examined.

Overall, the research broadly agrees that income is positively correlated with overall life satisfaction, while more recent research indicates, contrary to previous findings, that day-to-day happiness is also positively correlated to higher income, even at higher income levels.

It is important to note, however, that these findings are all correlations and are not necessarily causal. In fact, there are several other factors that can influence the relationship between income and happiness, which may explain why higher income doesn’t always lead to greater happiness for everyone.

How ‘Time Poverty’ Mediates The Income-Happiness Relationship

While the previously discussed research demonstrates a positive correlation between income and happiness for the population taken as a whole (and also for financial advisors in particular), advisors will likely recognize that this will not necessarily apply to every client. For example, a client with $300,000 of income who is in poor health and going through a divorce is less likely to be happy than one with $100,000 of income, a fulfilling career, and strong relationships. Therefore, it is important to consider the other factors that can affect the relationship between income and happiness.

One of the mediators of the correlation between income and experienced (day-to-day) happiness in Killingsworth’s research was the concept of ‘time poverty’, measured by the question “Do you have too little time to do what you’re currently doing?”. He found that the number of people responding ‘yes’ to this question increased as income rose, serving as a small but significantly negative mediator of the association between income and experienced wellbeing (so that the association between income and experienced wellbeing was significantly steeper when time poverty was held constant).

Nerd Note:

Killingsworth also found that people’s sense of control over their lives accounted for 74% of the association between income and experienced wellbeing, suggesting that higher incomes allow individuals to take greater control of their lives as they might have to worry less about meeting their basic needs. This also helps explain why experienced wellbeing tends to fall for high-income individuals who feel time-impoverished, as their time constraints reduce their ability to control their lives.

While perhaps not surprising, this finding does suggest that if an individual decides to increase their income in the pursuit of greater experienced happiness, they will also want to be aware of whether doing so will affect the time they have available for their other responsibilities and interests. Additionally, recalling that the data show happiness increases as income rises on a logarithmic basis, the same increases in income in absolute terms may result in smaller boosts to happiness as income rises.

Example 1: Linus currently makes $50,000 per year. He is considering a new position that will give him a $5,000 raise (10% of his current income) but will require him to work an additional 5 hours each week.

Linus’ sister Lucy is considering a job change that will pay her $6,000 more per year and that would also require an additional 5 hours of work per week.

Because Lucy currently makes $300,000 per year, the $6,000 raise represents only a 2% pay bump, so, according to Killingsworth’s research, she might be expected to experience less of a happiness boost than Linus will from the 10% raise that comes with his new job.

As the above example shows, improvements in experienced wellbeing from income depend on multiple factors. And Kitces Research shows that these findings apply to financial advisors as well.

How ‘Time Poverty’ Affects Financial Advisors

Our 2021 Kitces Research on “What Actually Contributes To Advisor Wellbeing” explored a variety of factors that contribute to advisor wellbeing (measured as the extent to which advisors experience their “best possible life”). While the positive relationship between advisor take-home income and happiness was previously discussed, it is important to consider other factors at work, as well as the more complicated relationship between advisory firm-owner happiness and firm revenue.

According to Kitces Research, weekly hours worked were inversely correlated with advisor wellbeing, with advisor wellbeing declining steadily as the hours worked by advisors increased, ranging from fewer than 30 hours per week to more than 60 hours per week. And thriving advisors don’t just tend to work fewer hours; they also tend to take more vacation days as well – those with the greatest reported wellbeing took a median of 25 vacation days per year compared to those who reported lower wellbeing who took a median of 15 days off.

Notably, the differences between thriving and struggling advisors were not just seen in the number of hours worked, but also in the allocation of their work hours to different activities. For instance, while thriving advisors spend an average of 24% of their time meeting with clients (likely one of the main reasons they became an advisor in the first place), struggling advisors spend 17% of their time with clients. At the same time, struggling advisors spend 6.3 hours per week on business development (likely not the main reason they got into the business), compared to only 3.8 hours for thriving advisors.

While all advisors have a range of competing needs (from meeting with clients to preparing plans to business development), limiting the hours spent on less-desirable tasks can not only make the workday more enjoyable but also reduce feelings of time poverty, which, as previously mentioned, tends to reduce wellbeing. And while some work on less-desirable tasks is inevitable, there are ways for both newer and more experienced advisors to spend more time on their preferred work activities and free up time for leisure (which, combined, can increase overall wellbeing).

How Advisors Can Mitigate ‘Time Poverty’ And Improve Their Wellbeing As Their Income Grows

As previously discussed, both Killingsworth and Kitces Research show the wellbeing benefits of additional income and the danger of time poverty (i.e., taking on so much work that one feels as though they do not have enough time to get everything done even if the additional work results in higher income!). Importantly, this can affect advisory firm owners at all levels of experience, and Kitces Research has identified revenue thresholds where advisor wellbeing tends to dip, as well as potential ways to promote greater wellbeing at these points.

The Potential Benefits Of Adding Staff As An Advisory Firm Grows

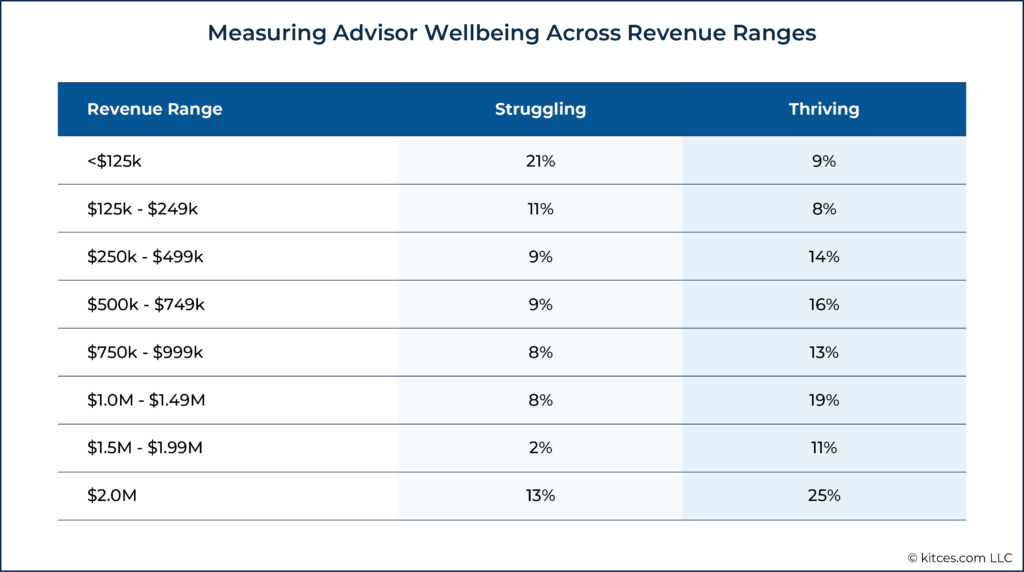

The 2021 Kitces Research on advisor wellbeing found that advisor happiness does not increase linearly with revenue, but rather that there are a few revenue thresholds where advisor wellbeing can stagnate and dip. These typically occur at pain points where the firm has grown large enough that the firm owner has too much work on their plate. But at each level, hiring certain staff members can help alleviate this burden (and mitigate the firm owner’s potential experience of ‘time poverty’).

For instance, once a firm reaches $250,000 in revenue, the workload for the firm owner often becomes heavy enough that they look to make their first hire in the form of an administrative assistant or a client services associate. This can reduce the amount of time the advisor has to spend on more administrative tasks (and the task of finding this employee can be outsourced as well!), allowing them to focus on more enjoyable and/or profitable activities or even reducing their total hours worked (though at the cost of compensation for the new staff member). This is suggested in the table below by the decrease in advisors reporting they are struggling at this revenue range, and the corresponding increase in those reporting they are thriving.

Next, once a firm reaches $750,000 to $1M of revenue (when the advisor is managing 75-100+ client relationships), advisors sometimes see another dip in wellbeing. This can be due not only to the time crunch faced by the lead advisor (as they have to both prepare plans for and meet with all of the firm’s clients) but also to the sheer number of relationships they can balance at once. And like the smaller firm, making another hire at this point – often an associate or service advisor – can again free up the lead advisor’s time for more profitable or interesting activities, which possibly contributes to the boost in the number of thriving advisors as their firms cross the $1M revenue threshold.

Finally, once a firm reaches the $1.5M-$2M revenue range, it has typically grown to the point that the founder is no longer capable of managing client relationships and an increasingly larger firm. As firms enter this revenue level and beyond, founders can choose to make additional strategic hires, whether it is an operations manager (who can help manage the operations of the increasingly complex business), personnel managers (to be in charge of the day-to-day management of the growing staff roster), or another lead advisor to provide further business development support (or perhaps all three as the firm grows!).

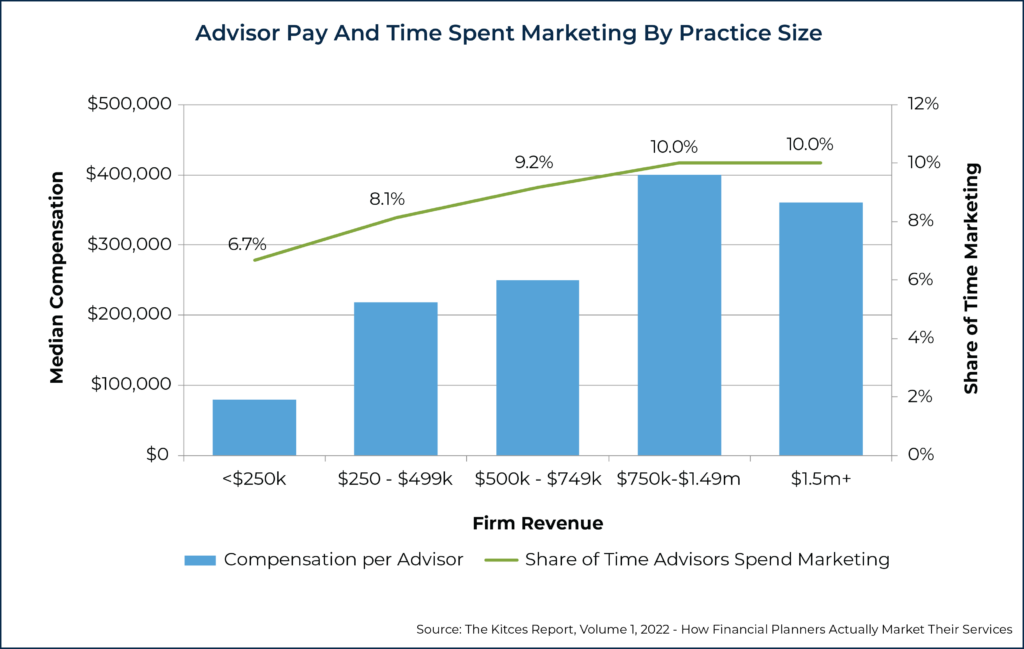

Managing The Time-Money Tradeoff

A related consideration for advisory firm owners is how to balance the value of their time against the costs of outsourcing certain tasks, particularly as the firm grows and the owner’s time becomes more valuable. For instance, when it comes to marketing, firms both have ‘hard-dollar’ costs (money paid to outside vendors for marketing) as well as ‘soft-dollar’ costs (the cost of the advisor’s time). Under this framework, a newer firm owner might choose to spend more time on marketing, as they have fewer clients to serve, while the owner of a more mature firm might spend more hard dollars on marketing in order to maximize their time spent meeting with clients (which the advisor might find more enjoyable as well).

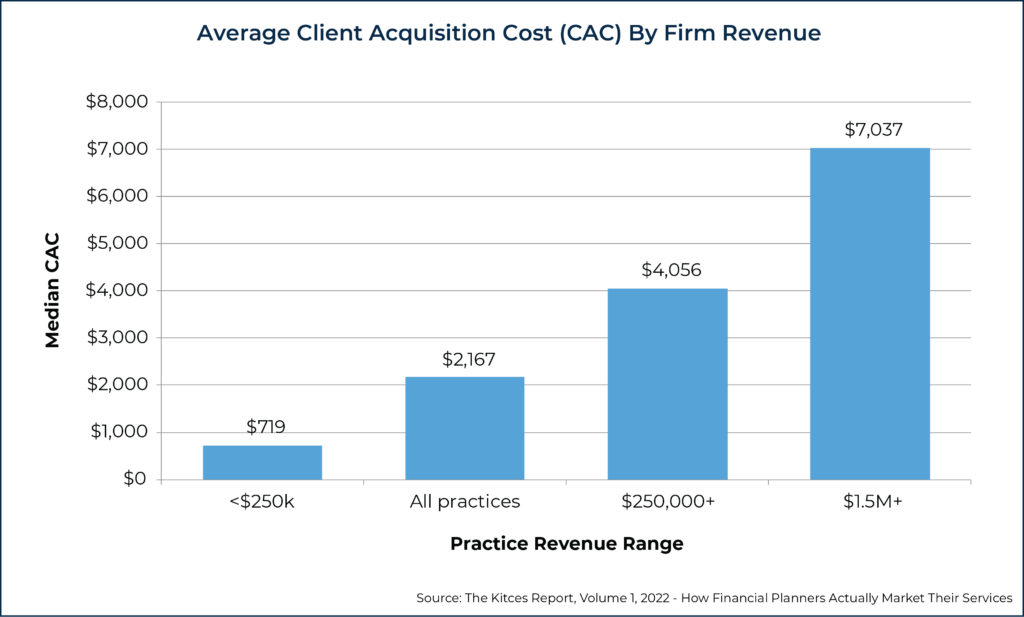

But the 2022 Kitces Research on How Financial Planners Actually Market Their Services found that the largest firms actually tend to spend a smaller percentage of their revenue on hard-dollar marketing costs and a larger percentage of their revenue on soft-dollar marketing expenses compared to smaller firms!

And this mismatch comes at a cost to these larger firms, as their average client acquisition cost ($7,037) is significantly higher than the average of all practices ($2,167). Which suggests that as an advisor’s time becomes more valuable, it can make economic sense to outsource tasks like business development to free up time for more high-value activities (or perhaps additional time away from work to prevent the damage to wellbeing that can occur as a firm reaches higher revenue levels!).

Further, another way a firm owner can generate more time is by determining which of their clients have become unprofitable (or unenjoyable) to serve and then ‘graduating’ those clients to another advisor. In this way, the advisor can focus more of their time working with clients who are profitable and value the advisor’s service, and at the same time free up additional hours for business or personal needs.

Notably, the idea of trading money for time to increase wellbeing has the backup of research. In their book, Happy Money: The Science of Happier Spending, researchers Elizabeth Dunn and Michael Norton found that using money to buy time is one of five key ways to improve happiness. This can apply to one’s personal life (e.g., paying someone to clean your house so you can spend that time on leisure), as well as in one’s workplace (e.g., an advisory firm owner who purchases a software tool that saves them several hours per month that could be used for leisure). Further, advisors can use this insight both for themselves (as they consider time/spending tradeoffs in their business) as well as for clients (to help them make the most of their money)!

Notably, the idea of trading money for time to increase wellbeing has the backup of research. In their book, Happy Money: The Science of Happier Spending, researchers Elizabeth Dunn and Michael Norton found that using money to buy time is one of five key ways to improve happiness. This can apply to one’s personal life (e.g., paying someone to clean your house so you can spend that time on leisure), as well as in one’s workplace (e.g., an advisory firm owner who purchases a software tool that saves them several hours per month that could be used for leisure). Further, advisors can use this insight both for themselves (as they consider time/spending tradeoffs in their business) as well as for clients (to help them make the most of their money)!

Ultimately, the key point is that as an advisor’s income increases, their wellbeing – in terms of both day-to-day happiness as well as overall life evaluation – can have a tendency to increase as well. But if the higher income comes with increased demands on the advisor’s time, particularly if they get to the point where they feel they don’t have time to finish everything they need to get done, the experienced ‘time poverty’ can have a negative effect on the advisor’s wellbeing.

This suggests that by spending more of their ‘hard’ dollars to bring on additional staff, invest in technology tools, and/or outsource tasks such as marketing, advisors can potentially free up their time and boost their happiness. Because in the end, time is the ultimate scarce resource, and it is important for advisors to spend it wisely, particularly as their income increases!