Executive Summary

A topic of increasing discussion amongst financial advisors is whether it’s truly necessary to dress up in order to attract and retain clients, and whether it might instead be better to adopt more casual attire – either because such attire makes it easier to connect with clients, or because some very experienced and successful advisors have adopted such wardrobes, seemingly with no negative impact on their success. But the reality is, just because a more casual style may work for seasoned and successful advisors, does not mean that it will work for all advisors.

In this guest post, Derek Tharp – our Research Associate at Kitces.com, and a Ph.D. candidate in the financial planning program at Kansas State University – explores the concept of “countersignaling” and what the research shows are the implications it may have for the decision to dress down – particularly amongst younger and newer advisors.

In economics, signaling refers to the ways in which we try to convey information to another party under conditions in which credible communication is difficult. For instance, when meeting with a prospective client, financial advisors may need to engage in certain forms of signaling in order to demonstrate their competency (e.g., becoming a CFP professional), since all advisors trying to win over a prospect would have an incentive to claim they are competent, regardless of their true level of knowledge. By contrast, countersignaling is a strategy which refers to ways in which we may try and demonstrate an even higher level of status by not signaling (e.g., a mid-level student may eagerly attempt to answer an easy question in class, while a high-level student may not, as a signal that their knowledge surpasses the point at which they would take pride in answering such a question).

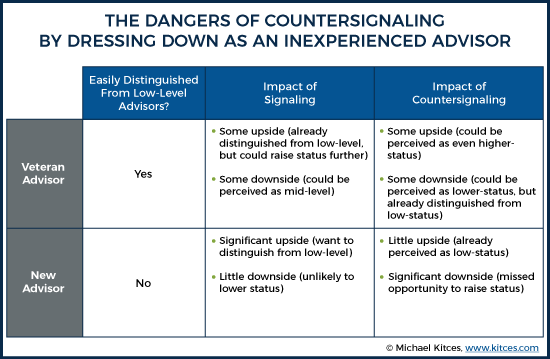

In an attempt to explain such countersignaling behavior, prior research has used game theory to demonstrate why signaling can be an effective strategy for mid-level individuals with regard to some characteristic (to demonstrate they are not low-level, and to hopefully be perceived as high-level), while countersignaling may actually be more effective for high-level individuals (as they are unlikely to be mistaken as low-level, and signaling could actually give the perception they are mid-level). And this dynamic may have direct implications for the decision to dress down as a financial advisor, as it could be the case that dressing down actually increases the status of an experienced and successful advisor, while dressing down might decrease the perceived status of a young and inexperienced advisor.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that it isn’t still wise to consider other factors, such as a particular client niche (and their typical dress/attire), when deciding whether or not to dress down. But given that many people prefer to not dress up, advisors – and particularly those who are young and inexperienced – should be careful not to skip out on opportunities to signal credibility to prospective clients, and be especially cognizant of the fact that just because seasoned advisors can dress down successfully, does not mean that young and inexperienced advisors can, too!

Success And How Advisors Dress

How we dress is an inherently personal topic. What we wear conveys messages about who we are, what we value, and who we hope to become. As a result, talking about dress and “appropriate” clothing can be a touchy subject. But it’s not a topic that financial advisors should shy away from, as our dress can have a real-world impact on our professional success.

One particular consideration is whether advisors really need to dress up in business formal attire to attract and retain clients, or whether it’s OK to “dress down” more often. In fact, some advisors believe it’s better to dress down, and see it as a way to better connect with clients by wearing attire that is more in line with what clients themselves would wear. Others have acknowledged industry shifts more broadly, and that consumers may be becoming more accommodating of less formal clothing. After all, it’s not difficult to find a lot of experienced and successful advisors who regularly dress down, and have clearly still been successful.

Yet, the caveat is that what works for a subset of experienced advisors doesn’t necessarily work for all advisors, and especially not for younger and inexperienced advisors. Often the discussion surrounding advisor dress will treat advisors as some sort of amorphous group, or at least one that is hard to classify beyond the clientele they are targeting. But the reality is, regardless of one’s target clientele, the decision to dress down can have very different implications based on an advisor’s experience and (perceived) level of success. In particular, “countersignaling” (i.e., the strategy of showing off by not showing off) can be a powerful strategy for some, but completely backfire for others!

Signaling Theory And How We Impact Perceptions By How We Dress

In economics, “signaling” refers to the ways in which one party can credibly convey information to another party under conditions of asymmetric information – for instance, how job applicants might signal the quality of their skills to an employer, when the applicants inherently know more about their skills than an employer possibly can, and the applicants (regardless of their true quality) have an incentive to portray themselves in as positive of a light as possible.

Nobel laureate Michael Spence’s seminal article on signaling within the job market first proposed signaling as one way for parties to overcome these problems of information asymmetry. In particular, Spence evaluated the role that education might play as a signaling mechanism in the job market. For example, while it can be hard for an applicant to credibly convey their true intelligence or work ethic when applying for a job, a Finance degree from State University at least indicates that an applicant has a combination of work ethic and intelligence that was capable of generating a particular GPA at a particular caliber of school.

A key aspect of signaling is that, in order to be credible, the signal itself must be costly to send. If the signal were free to send, everyone would send it, and, therefore, it wouldn’t convey any credible message. Additionally, there must be some condition present which otherwise prohibits credible communication, and therefore limits the ability of the party with less information to simply make the assessment effectively on their own. One such example is the inherent conflict of interest that always exists between a buyer and seller of any good or service – where the seller/provider is “always” trying to make everything seem appealing to a prospective buyer/customer/client.

For example, suppose a buyer and seller are discussing the potential sale of a piece of art. In this case, there’s no need to “signal” the current condition of the art, as the seller can simply let the buyer examine the art and determine the condition for themselves. But if the authenticity of a piece of art is an important aspect of its value, then the seller will want to have a credible way to signal the art’s authenticity to the buyer. Since merely stating that a piece of art is authentic is a costless activity (and it is exactly what both a fraudster and a genuine art dealer would claim), genuine sellers may instead pay for an appraisal by an independent and trustworthy third party to credibly signal the authenticity of the art to prospective buyers. Meanwhile, fraudsters won’t make a similar investment, as the cost will not enhance the value of fraudulent art.

(Note: The relevance of signaling within a financial advisory context is immediately apparent here, as we often have nothing tangible to show prospective clients, and must instead try to sell an invisible service.)

Another key aspect of signaling is that the costs of signaling will vary based on the true status of the underlying information that is known by one party yet hard to credibly convey to others (e.g., effectively signaling intelligence will be easier [i.e., less costly] for someone with a higher level of intelligence). This often comes up in the context of hiring decisions, and particularly in the debate over whether college education is primarily a way of building human capital or simply signaling one’s ability to employers.

From the signaling perspective, going to college might still be a valuable investment for students even if they don’t retain any skills or knowledge in the long run, as the opportunity cost of sending the signal to future employers (the time, effort, and money required to acquire a degree) is lower for students who exhibit traits that are attractive to future employers, such as higher intelligence and good work ethic.

In other words, all else equal, a student with lower levels of intelligence or work ethic is going to need to invest more in order to achieve the same degree and GPA as a student with higher levels of intelligence or work ethic. This cost may be a financial cost (e.g., paying more due to re-taking classes, tutoring services, etc.), a time cost (e.g., graduating in 5-years instead of 4, studying more, etc.), or simply a lifestyle cost (e.g., putting forth more effort and experiencing more stress to achieve the same outcome) – but the key point is that the opportunity cost is lower for a student with traits that an employer may find valuable, and therefore individuals with those traits may be more likely to invest in sending that signal.

In a financial advisory context, there’s a high degree of informational asymmetry between financial advisors and prospective clients. Assuming that nearly all financial advisors are at least more knowledgeable than the average consumer, it is then hard for financial advisors to credibly convey the true quality of their knowledge or services to consumers. In other words, it is difficult for a less knowledgeable consumer to differentiate a “merely good” advisor from an exceptionally knowledgeable, skilled, or otherwise more qualified advisor. Additionally, consumers cannot trust an advisor’s assessment of their own knowledge, as both fraudsters and competent advisors would (costlessly) claim to be knowledgeable advisors (or, similarly, claim to be fiduciaries acting in their clients’ best interests).

Of course, certifications and designations are one way that advisors can engage in signaling. A consumer can credibly know that a CFP professional has at least achieved a minimum level of education and competency. But given that consumers in many markets now have 10s if not 100s of CFPs to choose from, such signaling is increasingly just table stakes, and advisors still need to engage in other forms of signaling.

Countersignaling And Enhancing Perceived Status By Not Showing Off

An important concept related to the decision to “dress down” in an advisory context is “countersignaling”. While “signaling” refers to engaging in a costly behavior to credibly convey a message, “countersignaling” refers to avoiding a costly behavior to similarly convey a message in a credible manner, albeit in an even higher-status way.

Feltovich, Harbaugh, and To (2002) developed a model of countersignaling to examine such behavior, which was subsequently supported by their experimental research. Feltovich et al. note that contrary to prior models which implied that the highest status individuals would invest the most in signaling, it’s often those of mid-level status who are most eager to engage in signaling behavior. To support this point, they give examples such as:

- “The nouveau rich flaunt their wealth, but the old rich scorn such gauche displays.”

- “Mediocre students answer a teacher’s easy questions, but the best students are embarrassed to prove their knowledge of trivial points.”

- “Acquaintances show their good intentions by politely ignoring one’s flaws, while close friends show intimacy by teasingly highlighting them.”

Using game theory, they examine why this might be. After laying out different incentives and noting how different participants might act within a “noisy” environment of imperfect information and uncertainty, they find that signaling is often a rational behavior amongst medium quality signalers, while countersignaling is often rational (and possibly even more effective) amongst high-quality signalers.

To get a better understanding of what their model is saying, imagine that we separate financial advisors into three categories: low quality, medium quality, and high quality.

(Note that quality is intentionally vague here, but think of “quality” from a consumer’s perspective, which will likely be an overly simplified, imperfect, and possibly even “wrong” conception of advisor quality, such as an advisor’s personal success in the business.)

Noting that consumers and advisors engage in a “noisy” market with lots of imperfect information and uncertainty, it’s going to be hard for consumers to precisely place advisors in any particular category. Instead, they’ll have to rely on contextual clues available to them to try and determine the quality of an advisor.

Example 1. Assume Advisor A is a CFP certificant, works for a prestigious firm, works out of premium grade office space, and has been in the business for 25 years; Advisor B is also a CFP certificant, runs their own RIA, has three support staff, works out of mid-tier office space, and has been in the business for 10 years; and Advisor C is studying to become a CFP professional, runs their own RIA, works out of a home office, and has been in the business for 3 years.

Assuming all three advisors make a favorable impression on a prospect in an initial meeting, I think it may be reasonable to suspect that a typical consumer might rank the advisors (in terms of quality, from highest to lowest) as follows: Advisor A > Advisor B > Advisor C

(Note: Of course, these may not be accurate representations of advisor success at all. The inexperienced advisor with a home office may have the most business success of the three, but in a noisy and uncertain environment, that’s not the high probability estimate a consumer is likely to make.)

Further, assume that while all three advisors would ideally prefer to be perceived as a highest-tier advisor, each believes that an impartial assessment would place them in the following categories: Advisor A (highest-tier), Advisor B (mid-tier), and Advisor C (low-tier). If this were the case, Feltovich et al.’s theory would suggest that each advisor might be more or less willing to engage in signaling behavior depending on their perceived standing.

Relative to Advisors A and B, Advisor C likely realizes that they have genuine deficiencies that inhibit their ability to signal the highest level of quality. Both advisors have far more experience and a larger client base that presumably can at least sustain a support staff or employment at a prestigious firm. As a result, signaling strategies that attempt to position Advisor C to compete on perceived status are likely to be ineffective. Not only will the relative costs of such strategies be higher, but signaling and losing out to a medium quality advisor results in a worse outcome than just not signaling at all (by wasting the time and cost of trying, instead of focusing on finding clients who won’t use such signals as evaluative criteria in the first place).

Meanwhile, Advisors A and B have different incentives. Unlike Advisor C, who may perceive the gap between their current standing and the highest tier advisor to be too large to overcome, Advisor B has stronger incentives to signal. First, Advisor B wants to distinguish themselves from lowest-tier advisors. Additionally, Advisor B would prefer if their signaling could move them into the highest-tier of advisors. This combination of incentives, both distinguishing oneself from a lower-tier and moving oneself to a higher-tier, is why Feltovich et al. find that signaling is most attractive to mid-level individuals.

By contrast, signaling may not be as attractive for Advisor A, because the contextual clues available to the consumer – some of which are themselves signals of a different sort (long tenure, premium grade office, prestigious firm, etc.) – make it unlikely that Advisor A will be perceived as a lowest-tier advisor. As a result, unlike Advisor B, Advisor A does not need to worry about distinguishing themselves from the bottom tier. Further, because mid-tier advisors have a strong incentive to signal and presumably will signal often, signaling could actually run the risk of lowering the perceived status of the high-tier advisor by making them look like a mid-tier advisor who’s just trying to appear as higher status. And this is where the power of countersignaling comes in. Under the right circumstances, countersignaling demonstrates a level of confidence that may be perceived as even higher status than signaling.

The Important Juxtaposition Of Context And Attire In Countersignaling

When the topic of “dressing down” comes up in a financial advisory context, it is important to acknowledge the broader contextual environment. Of course, dressing down may not be dressing down at all if an advisor is still “dressing up” relative to their broader environment (as has been noted by those who dress down to match the clothing style of a specific client niche). But setting this sort of “dressing down” aside, there is risk in inexperienced advisors seeing experienced advisors successfully countersignal and reaching the wrong conclusions about the importance of attire. Because the contextual environment of an experienced advisor is fundamentally different than an inexperienced one, the impact of dressing down may not be the same.

Example 2. Going back to the prior example of Advisors A, B, and C: Assume that business formal is the standard consumer expectation amongst each advisor's target clientele. Further, assume that all of the advisors know each other and engage regularly at local events and industry conferences. Now suppose that 12-months ago Advisor A decided to go fully business-casual in attire, and has been pleasantly surprised with the results. Advisor A shares with Advisors B and C that not only has it not appeared to hurt their business, but things seem to be getting even better.

In this situation, there is a danger in Advisors B or C concluding that they too would not be negatively impacted if they bucked the norms and expectations of consumers and decided to dress down. Yet countersignaling, given the full context of Advisors B and C’s situations, may not come off as confident and status-raising. Instead, it may just make them look less professional, lowering their perceived status and ability to attract and retain clients.

It is true that seeing someone dress business casual within an environment where most are dressed business professional stands out, and possibly in a good way if pulled off well. But seeing someone dressed business casual in an environment where everyone else dresses business casual (e.g., a mid-tier office complex), just doesn’t have the same effect. Adding in the additional factors that fill out the full contextual evaluation that consumers are likely to make, the reality is that Advisor A has likely built both the social and human capital that might allow them to pull off countersignaling, whereas Advisors B and C have not.

Career Stage Matters In Choosing Proper Attire As A Financial Advisor

Simply put, it may be risky for inexperienced advisors to look towards experienced advisors for guidance on how to dress, and particularly if they are picking up countersignaling behavior that may not apply within their own individual context. While there's certainly a lot that younger advisors can learn from their more experienced colleagues (and it's great that many experienced and successful advisors are willing to help give advice and guidance to younger advisors), it’s crucial to remember that – as with any financial planning advice – it must be appropriate to the individual’s own circumstances.

And the reality is, even most of those experienced and successful advisors themselves rose up through more “traditional” ranks, and achieved a certain level of success before going in a different direction. Dressing down with an existing client base – where many clients already know and trust an advisor – is not necessarily the same as dressing down when growing a practice from scratch. Similarly, growing a practice where you have to meet new clients and get to know them from scratch is different than growing a practice by generating referrals from existing clients – where there is likely a higher degree of social capital coming into the referrals relationship, which can either reduce negative perceptions related to dressing down or enhance the countersignaling effect.

Of course, dress is just one of many factors, and surely there are examples of advisors who have launched and grown successful practices eschewing formal attire at all stages of their career. But it is still worth contemplating what impact, if any, dressing down might have on success. Particularly given that many young advisors (myself included) don’t seem to love formal business attire, it can be easy to engage in some motivated reasoning that leads us to the conclusions that we want to reach – ignoring the real-world psychology from a client’s perspective.

Or viewed another way… if you’ve ever had the frustration of losing a prospect to some slick-but-clueless salesperson, recognize that this is a quintessential example of how hard it really is for a typical prospect to understand who is and isn’t a credible advisor. It may not feel “fair” that consumers often rely on intangibles like how an advisor dresses to select an advisor, but in the face of a difficult decision with few “clues” to go on, any potential signal about the credibility of the advisor matters. So beware of skipping out on the signaling opportunities that are implied in how you dress as an advisor… at least, unless you’re really certain you can pull off a countersignaling strategy successfully! (But remember, the fact that other experienced advisors can do it still doesn’t mean you can, too!)

So what do you think? Can dressing down have different effects based on the experience and perceived status of an advisor? Should inexperienced advisors fight the urge to dress down? Are there other ways advisors can signal or countersignal with their dress? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!