Executive Summary

The tax-free nature of growth on a Roth IRA makes it a highly appealing investment account to hold, and a similarly appealing type of account to inherit. All else being equal, it’s clearly better to be the beneficiary of an account that will never be taxed, than one that will be taxed over time.

However, the caveat to leaving a Roth IRA as an asset to inherit is that doing so implicitly means that the original IRA owner will have paid taxes to get money into the account, either through systematic contributions spanning many years, or possibly through a large Roth conversion (or a series of partial Roth conversions over time). Which means the benefit of inheriting a Roth IRA is actually more nuanced – if the IRA owner pays “too much” in taxes to create the Roth, the beneficiary may have been better off to simply inherit a traditional IRA and pay the taxes themselves instead!

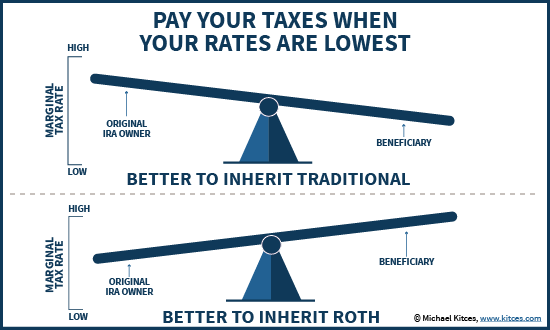

In fact, ultimately the decision of whether to bequest a Roth or traditional IRA should be driven by a comparison of the original IRA owner’s marginal tax rate, and the expected marginal tax rate of the beneficiary in the future. If the beneficiary’s tax rates are higher, it’s clearly beneficial for the current IRA owner to go ahead and convert the IRA, paying the taxes now at current rates, and leaving the (high income) beneficiary a tax-free account. However, if the reality is that the beneficiary’s tax rates are actually lower – perhaps because the original IRA owner’s wealth is being spread across multiple beneficiaries, because the beneficiary simply has less income and assets, or maybe just due to the fact that the beneficiary lives in a different state that has a lower tax rate – then the best thing a (higher-income) IRA owner can do is simply to leave a traditional IRA to the beneficiary and let the beneficiary pay the taxes at his/her own lower tax rates!

Roth Vs. Traditional IRAs – Pay Your Taxes When Your Marginal Tax Rate Will Be Lowest

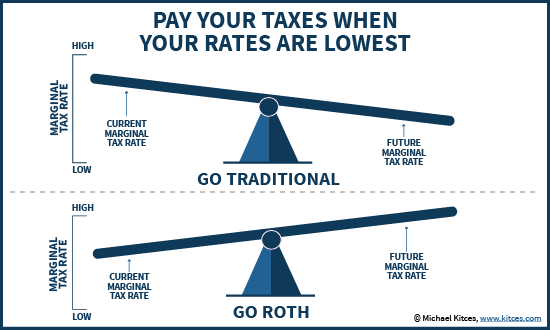

Although there are several factors that determine whether a Roth or traditional IRA will be best, the dominating factor that most drives the outcome is a comparison of an individual’s current versus future marginal tax rates. When tax rates remain the same, final wealth remains the same; when tax rates change, final wealth may be better or worse, depending on the direction of the change. If rates are higher in the future, it’s better to have converted now to a Roth; if rates are lower in the future, it’s better to simply keep the traditional IRA, wait, and pay the taxes in the future when the rates are lower.

For those who are working, the decision about whether to contribute to a traditional or Roth IRA often becomes an evaluation of current marginal tax rates (on top of wages and any other income) versus what that marginal rate will likely be in retirement (when wages are gone, but a pension, Social Security, or other income may be present). Those in their peak earnings years will often be better to contribute to a traditional IRA – taking the current high-tax-rate deduction and withdrawing in the future at lower rates once wages are gone – while those with lower earnings years (perhaps young workers whose income and wealth is still growing, or someone who was unemployed for part of the year) are generally better off contributing to a Roth instead. In some cases, tax rates in retirement may be lower simply because there’s a plan to relocate upon retirement to a state with significantly lower tax rates (e.g., from New York to Florida, or from California to Texas) and the change in state tax rates alone drives the outcome.

For those already in retirement, the decision-making process is similar, although the income factors may be slightly different. For those who retire early – e.g., in their 50s or early 60s – there is often an opportunity for Roth conversions while rates are especially low, before Social Security benefits begin (as the phase-in of taxation on Social Security benefits can dramatically increase the marginal tax rate). On the other hand, even those in their 60s may wish to do significant ongoing Roth conversions, to mitigate the tax impact of higher income in their 70s once Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) begin. Nonetheless, the fundamental point remains the same – to time income from year to year so the movement of money to a Roth occurs when tax rates are lower, and avoid being forced to take the money out when tax rates might have been driven higher in the future.

The Value Of Inheriting An IRA – Owner Tax Rates Vs IRA Beneficiary Marginal Tax Rates

In the case of an IRA that will not be fully used by the original IRA owner and will be bequested to a beneficiary, the decision about whether it’s better to leave the beneficiary a traditional IRA or a Roth IRA actually still follows the same formula – what is the tax rate now (on the current IRA owner if he/she converts), and what will the tax rate be in the future (when the beneficiary will ultimately withdraw the funds).

In other words, in the inherited IRA context, the evaluation of whether tax rates will be higher now or in the future is essentially a measure of whether the beneficiary’s marginal tax rate is going to be higher or lower than the original IRA owner. If the beneficiary’s tax rate will be higher than the current IRA owner, it’s better to convert to a Roth now. If the beneficiary’s tax rate is lower, though, it’s better to simply leave the beneficiary a traditional IRA and let him/her liquidate it at the beneficiary’s own lower tax rate!

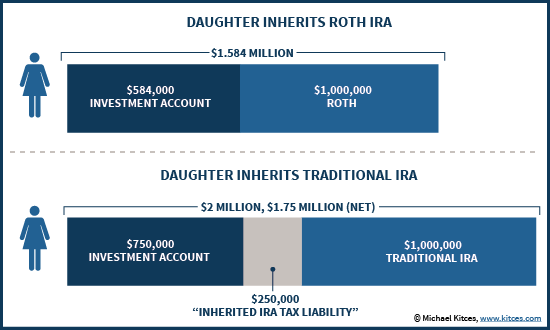

Example. A parent has a total of $2M of assets, including a $1M IRA and a $1M investment account. Due to Social Security benefits and an ongoing pension, the (individual) parent is already in the 28% tax bracket, but hardly spends any of the assets as the Social Security and pension benefits alone are sufficient to cover expenses. The parent decides “it would be great to leave a tax-free Roth to my daughter” and converts the $1M IRA, resulting in the first $100,000 (approximately) being taxed at 28%, the next $220,000 being taxed at 33%, and the remaining $680,000 taxed at 39.6% as the large conversion fills up all the tax brackets. In addition, the parent lives in Colorado, and faces an additional 4.63% state tax rate. This results in a total tax bill of over $416,000 (a marginal tax rate of 41.6% across the blended tax brackets), which means the child will inherit a $1M Roth IRA and $584,000 in a brokerage account (net of the $416,000 in taxes).

However, the 28-year-old daughter herself is a schoolteacher in Texas earning a modest income, putting her in the 25% tax bracket, and Texas has no state income taxes. As a result, if the daughter simply inherited the $1M IRA and the $1M investment account, the IRA would be taxed at an average rate of only 25% (stretched out over time, given that RMDs for a 28-year-old start out at less than 2% of the account balance). Thus, by simply inheriting the traditional IRA and not the Roth, the daughter will ultimately only face approximately $250,000 of taxes on the IRA, instead of losing $416,000 to taxes by having the parent convert it - a total of $2M gross (or $1.75M net) with the traditional IRA versus only $1.58M with the Roth!

Notably, in situations where a beneficiary inherits a traditional IRA and not a Roth, the beneficiary will not only face taxes on the traditional IRA itself, but will also face taxes on the future growth. However – as indicated above – this isn’t necessarily problematic, because the beneficiary will also have more money available to pay those taxes anyway! In the above example, the $166,000 difference in taxes provides a significant amount of “excess” inheritance dollars (which itself can grow over time as well) to cover future tax liabilities of the inherited IRA! Thus, while inheriting the traditional IRA does mean future growth of the IRA account will also be taxable, the daughter has another $166,000 of assets in the brokerage account (plus future growth on those tax savings!) to cover the taxes on the future IRA growth!

Factors To Consider In Evaluating Owner Vs Beneficiary Marginal Tax Rates

While evaluating the marginal tax rate of an IRA owner now is relatively straightforward – simply look at what income is already coming in, and determine the marginal tax rate for additional income beyond that point – there are a number of additional issues to consider when looking to the tax rates the beneficiary may face, including:

- State of residence of the beneficiary and its state tax rate (especially if different than the IRA owner’s state, as the difference in state tax rates alone can be as much as a 10%+ change in tax rates!)

- Employment income of the beneficiary (assuming he/she is of working age), along with any income generated by passive investment(s) of the beneficiary

- Increase in potential income due to other inherited assets (e.g., inheriting a taxable account that generates some passive income boosts the tax base and marginal tax rate of subsequent IRA income)

- Dissipation of assets and RMDs across multiple beneficiaries (e.g., a $2,000,000 IRA for an individual has rather sizable RMDs, but leaving a series of four $500,000 IRAs to four beneficiaries, each of whom stretches the account based on their own life expectancy, can dramatically reduce the magnitude and impact of RMDs)

In the case of multiple beneficiaries, an IRA owner may have to balance the needs of beneficiaries with very different tax situations – though converting to a Roth IRA when at least some beneficiaries will be in lower tax brackets still results in less overall family wealth. On the other hand, it’s also notable that if the IRA owner has charitable intent as well, it may be even more appealing to simply leave the IRA to a charity and use other (taxable account) assets to satisfy beneficiary bequests, especially if both the IRA owner and the beneficiaries are in a high tax bracket.

If the beneficiary of the IRA is going to be a trust, it may be especially appealing to go ahead and do the conversion to a Roth, as while trusts can qualify as “see-through” beneficiaries eligible to stretch the IRA, trusts that accumulate the IRA distributions inside the trust face the unfavorable trust tax brackets, with the 39.6% rate kicking in at just $12,150. On the other hand, if IRA distributions to the trust will subsequently be distributed through to the underlying beneficiaries, the trust will receive a DNI deduction and the income will flow through to the beneficiaries and their own individual tax returns, which means it may still be appealing to leave the trust a traditional IRA if the underlying beneficiaries have low tax rates.

Of course, a key caveat to all of this is the assumption that the beneficiary will actually stretch the (traditional) IRA, and not simply liquidate the IRA quickly upon inheriting it – which could drive the beneficiary all the way up to the top tax bracket! On the other hand, if the beneficiary is going to rapidly liquidate the account, then the beneficiary will not get much tax-free-growth-benefit from inheriting a Roth IRA either!

Notably, there have been proposals from the White House and Congress to do away with the IRA stretch rules and require (most) beneficiaries to use the 5-year rule. If this happens, future IRA beneficiaries may be unable to avoid the rapid acceleration of liquidating an IRA, driving up their tax rate upon liquidation if there is a sizable account. Though notably, a forced liquidation over 5 years would also again limit the tax-free-growth benefit from inheriting a Roth IRA, either, and really just reduce the analysis once again to whether the beneficiary of a traditional IRA (liquidating under the 5-year rule) will have a lower average tax rate than doing a Roth conversion for the original IRA owner beforehand.

Other Factors That Impact Inheriting A Roth Vs Traditional IRA

Beyond the considerations of tax rate differences between IRA owners and beneficiaries, it is notable that there are some other factors that can provide a slight tailwind benefit for converting to a Roth, all else being equal, including:

- Avoiding Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) during the life of the IRA owner. While an inherited IRA is subject to RMDs for the beneficiary, regardless of whether it is a traditional or Roth IRA, the original IRA owner faces RMDs for a traditional IRA and not a Roth. Thus, to the extent that the original IRA owner is anticipated to live materially beyond age 70 ½ when RMDs begin, there is a slight benefit to having a Roth, as it simply allows more tax-preferenced dollars to remain in the account. (However, the impact of avoiding RMDs is actually relatively minor until the IRA owner reaches an advanced age!)

- To the extent that the Roth conversion can be paid with “outside” dollars from a taxable account, it is slightly more efficient in the long run to bequest a Roth IRA than a traditional IRA plus a “side account” to pay the future taxes. This is due to the simple fact that the traditional IRA, by virtue of its account type, grows efficiently and tax-deferred, while the side account is taxable and grows less efficiently due to the ongoing drag of taxation on interest, dividends, and capital gains.

- Estates exposed to a state estate tax may benefit by doing a Roth conversion while the IRA owner is still alive, as paying the income tax liability for the IRA effectively reduces the size of the estate itself and potential estate tax exposure. Notably, this is not necessary for those subject to Federal estate taxes, due to the Income in Respect of a Decedent (IRD) deduction under IRC section 691(c), but it is beneficial at the state level since states generally do not allow a state IRD deduction.

Of course, not all of these “other” factors will apply in all situations, and in most cases these factors are still trumped by a material difference in tax rates between the IRA owner and subsequent beneficiaries. Nonetheless, these factors can provide a slight but material tailwind in favor of converting to a Roth, at least (or especially) if the IRA owner can convert systematically over time without necessarily converting so much in any one year that the current tax bracket is driven up too far.

The bottom line, though, is simply this – while there may be intuitive appeal to inheriting (or bequesting) a Roth IRA, if doing so comes at a cost of paying higher tax rates now (as the IRA owner) than the beneficiaries would have paid by simply inheriting a traditional IRA (along with other assets to cover the future taxes), then trying to leave a Roth IRA to beneficiaries can actually be a losing proposition and destructive for family wealth. In the end, the decision about whether to bequest a Roth or traditional IRA should be made by looking at who can ultimately extract the IRA dollars at the lowest possible tax rate for the family… the IRA owner, or the beneficiary!

You are right Michael. It is a bad things for people to inherit money. Fortunately, I am a masochist, I like the pain of inheriting money and having to pay taxes. So all your readers can put me down as the beneficiary, I will bear the burden for them. Joseph Alotta, SS# 309 52 1129.

This is the first world-iest of first world problems.

Mike,

Continuing our Roth discussion from a few months back, if you run the numbers Roth will almost always still be superior even with a reduced future tax rate if the bene’s stretch period isn’t jeopardized by a potential 5 year rule, particularly if the bene is a grandchild. Having said that, remember, conversion can be done piecemeal, over an extended period of time and at a guaranteed federal rate of no higher than the AMT rate of 28% through recharacterization. Roth will almost always win out over time.

You’re weekly reading is the best,

Thanks…

Mike Rubin

On my father in law’s passing, I was tasked with managing my mother in law’s money. The first thing I looked at was her marginal rate, 15% with room for conversions before hitting 25%. Each year, I convert (some) and then at tax time recharacterize to nail the taxable income right at the 15/25 line. After 10 years of this process, more than half her account is Roth. Her daughters will both have retirement income that puts then at either 15%, or 25%+. For the 15%er, The RMD won’t risk pushing her to 25% even if there’s a need to take a larger withdrawal than the RMD. For the 25%er (my wife), we are semi-retired, and at the edge of the line where more income would mean deferring real estate losses that have been carried forward for nearly 20 years. In other words, a phantom 37% bracket similar to the phantom brackets created by Social Security taxation.

In your examples, I agree 100% that a wholesale conversion pushing one from a 28% marginal rate to the 39.6% bracket isn’t wise. Any advisor recommending such things should go back to school.

As you mention, the big wild card is the elimination of the stretch IRA. That potentially changes your, and my, analysis of the conversion.

Last, Derek & dude, there are many financial issues that affect the 1%, but this one impacts anyone who will leave money to a beneficiary. Someone in the 10% bracket with $100K in her IRA can convert her way to the 28% bracket. And her adult beneficiary would be worse off by thousands of dollars that can put food on the table. This might provide $4000/year in RMDs to help with the budget. Not a 1% issue, but an issue that can hit anyone.

Excellent explanation, as expected from this author. I am in a position similar to JoeTaxpayer’s mother in law, and am well past 70. Fortunately, the combined income of me and my wife lets us stay in the 15% bracket, unless we need a large withdrawal from an IRA for unforeseen expenses.

So I continue to convert a bit of my IRA each year to a Roth, of which my daughter is the beneficiary, taking care to stay within the 15% bracket. Since my daughter makes a generous salary in a state with a high income tax, she pretty clearly will be paying a much higher tax rate. You need to run the numbers, but this strategy can work well if well planned. Small rub: That Roth conversion raises our AGI, and this exposes more of our Social Security to taxation, but the hit is small.

Oleditor,

Thanks for sharing.

Frankly, if your daughter’s tax rate is high enough – especially with a difference in state tax rates on top – you may even find that it’s worthwhile to do those partial conversions straight through the 25% tax bracket as well.

Either way, though, you’re implementing this in the exact manner being suggested in the article – by converting as much as/as long as your rates remain LOWER than the beneficiary’s. That’s the time it DOES pay to convert to a Roth. Pay your taxes when your rates are lowest!

– MIchael

Given that she probably has 40-50 years to live, I think it highly likely that taxes will generally go up by the time she is using the money, putting her in an even higher tax bracket than she is in now. We never know. I’m only worried that Congress will undermine the advantages of the Roth account later, however, just as it reversed the longstanding principle that Social Security would not be taxed, as it is often considered to be a return of the taxes the worker paid over a long working lifetime. I paid Social Security taxes continuously for more than half a century, and that perfidy still galls me.

Paid Taxes only to be Taxed on the passive income of what your tax income earned in later years.. However only if you exceed a certain life style threshold. Reagan did this? hmmmm Thought he was a fiscal conservative..

But if the beneficiary of the ROTH IRA continues to work, they now have tax free income that can allow the beneficiary to contribute more to a 401k type retirement plan. Or perhaps they qualify to fund their own ROTH IRA and now can afford to do so.

Tax free income is good!

If the beneficiary is in a lower tax bracket, the beneficiary would have had EVEN MORE MONEY to contribute by inheriting a pre-tax retirement account and the assets to pay the tax liability!

Tax free income is not good when it gives you LESS tax-free wealth to spend!

– Michael

The thing is it is not up to the beneficiary what type of money they inherit. While the deceased may know the tax situation of the beneficiary before dying that situation can change.

It is up to the beneficiary to make the best of their inheritance no matter how it is given.

Michael I would add one item for consideration. Qualified Roth distributions do not affect the calculations for taxing Social Security benefits. It’s another benefit to consider in the evaluation of the net effect of Roth IRAs. For many in the neighborhood of the ‘tax torpedo’ it becomes the most important consideration and can significantly change the outcome of any benefit calculation for Roth IRAs

Doesn’t the time value of money come into effect also? If I have $1,000,000 put into and ordinary IRA vs a Roth where I pay the taxes up front (assume a 30% tax rate), I have $700,000 in the Roth. Also, assume I am making 6% on those numbers each year. Aren’t I better off with the regular IRA of $1,000,000 making 6% as opposed to a Roth where taxes are paid up front leaving less money for the 6% investment generation? I’ve always believed that the longer one can defer a tax payment, the better.

The present value of the 30% tax bill on the $1,000,000 IRA discounted at that 6% is going to be the same $300,000 you paid to create the Roth now.

It’s actually the accounting for the time value of money that makes the scenarios equal. The present value of the tax bill at a 6% growth/discount rate will ALWAYS be the exact same $300,000 as long as tax rates don’t change.

– Michael