Executive Summary

With years of ongoing Federal budget deficits and a large and growing national debt, there is a common perception that "at some point" tax burdens must rise to address the issue. While the timing is not certain, the belief that higher tax rates may be inevitable has become a strong driver for many advisors and clients to do whatever they can to manage that future tax exposure. And one of the most popular strategies: take the tax exposure off the table altogether, by contributing to Roth accounts and doing Roth conversions, with the goal of paying taxes now when rates are lower and not in the future when they may be higher.

A closer look at paths to tax reform that can address Federal deficits though, reveal that while tax burdens in the aggregate may be higher in the future, marginal tax rates will not necessarily be higher. In fact, most tax reform proposals, from the bipartisan Simpson-Bowles to the recent proposals from Representative Camp, actually pair together a widening of the tax base and an elimination of many deductions with a lowering of the tax brackets! In addition, proposals to shore up Social Security and Medicare often involve simply raising the associated payroll taxes that currently fund them... tax increases that would result in a higher tax burden on workers, but no increase in the taxation of future IRA withdrawals. And the US remains one of the only countries that does not have a Value-Added Tax (VAT), which could also increase the national tax burden without raising marginal tax rates.

In the end, the simple reality is that there are many paths to higher tax burdens in the future that don't necessarily involve higher marginal tax rates on IRA withdrawals. Which means ultimately, advisors should be very cautious about doing Roth conversions - especially conversions at rates that are 33% or higher - and the best possible thing to do with a pre-tax IRA may simply be to continue to hold it, and wait for tax burdens to increase... because when paired with a compression of tax brackets that leads to lower marginal tax rates, not converting to a Roth could actually be one of the best long-run tax savings strategies around!

Roth Conversions And Marginal Tax Rates

When evaluating a prospective Roth conversion (or contribution to a Roth, versus a traditional account), the basic principle for maximizing long-term wealth is relatively straightforward: you should pay your taxes when the rate will be lowest. If your tax rates are higher now and will be lower in the future, keep the pre-tax account and wait and withdraw at those lower future rates. If your tax rates are lower now and will be higher down the road, convert/contribute to the Roth and pay the tax bill now at the more favorable rates.

The caveat to applying this approach, though, is that it’s crucial to understand what tax rates are being compared in the first place. Because a Roth conversion (or a future traditional IRA distribution) happens at the margin – on top of whatever income and deductions the person already has or is projected to have – it’s crucial to look at the true marginal tax rate, now and in the future. And that means more than just looking at an individual’s tax bracket, as phaseouts of tax credits and deductions based on income can cause marginal tax rates far higher than just the tax bracket alone.

At the same time, it’s also important to recognize that a marginal tax rate is just that – a tax rate, at the margin, on the last dollar of income. It does not necessarily speak to a person’s total tax liability, or the overall share of their income being consumed by taxes each year. That's measured by the effective tax rate.

Example. A married couple that earns $350,000 of ordinary income faces a marginal Federal tax rate as high as 39.8% (including a 33% tax bracket, a 2% impact for the phaseout of personal exemptions, a 1% impact for the phaseout of itemized deductions, and a 3.8% Medicare surtax on net investment income). However, their actual tax liability due would be only $85,231 (assuming 2 personal exemptions and $15,000 of itemized deductions, both partially phased out), which on a $350,000 income is equivalent to a 24.4% effective tax rate. In other words, while the couple may be adding income at the margin at almost 40%, their overall tax liability on the income already earned is not nearly that high. And if their (itemized) deductions were greater, their tax burden would be reduced and the effective tax rate would have been even lower for the couple, despite their marginal rate still being pegged at almost 40%!

Impact Of Tax Reform On Marginal Tax Rates

The reason this distinction between marginal and effective rates is so important is not merely that it’s crucial to use marginal (and not effective) tax rates to properly do the analysis in the first place. It’s that with a growing buzz for “tax reform” and resolving the ongoing Federal deficits, many clients (and their advisors) are increasingly concerned about the “risk” that tax legislation cause tax rates to be higher in the future. Yet here, again, it’s crucial to make the distinction regarding the impact of tax reform on marginal versus effective tax rates.

At a broad level, there are three fundamental levers that tax reform can adjust, if the goal is to generate more total taxes in the future:

- Expand the tax base by taxing more types of income/taxpayers/etc

- Keep marginal tax rates but reduce deductions

- Increase marginal tax rates

Notably, the first option may change the individual’s effective tax rate indirectly by potentially including more income in the formula for taxes in the first place, but it doesn’t change the marginal tax rate at all. In other words, taking more types of income or making more people subject to the income tax system in the first place can generate more taxes in total, without necessarily increasing their tax rates.

In the second option, the individual’s effective tax rates will rise, but there still isn’t necessarily any impact on the marginal tax rate, as the whole point of eliminating deductions is that it raises the tax burden on existing income, not the rate on the next new dollars income. For instance, if in the prior example we changed the law to limit deductions and it reduced the couple’s available deductions by $10,000, their tax liability would rise to $88,531 and their effective tax rate would be 25.3%, but their marginal tax rate would still be the same! Higher effective rates and a greater tax liability don't necessarily mean higher marginal tax rates.

Ultimately, it is only the third option – to outright increase marginal tax rates, such as by increasing the tax brackets – that actually results in a true increase in future marginal tax rates.

These distinctions are crucial, because the reality of tax reform is that it most often relies on the first and second options to increase taxes, and not necessarily the third. For instance, in the Tax Reform Act of 1986, a significant number of tax preferences and deductions were eliminated, the types of income being taxed were expanded (by eliminating a lot of real estate and other “tax shelters”), and the tax base was so widened that the top marginal tax rate fell from 50% in 1986 to only 28% by 1988 (and because the lower marginal rates were offset by fewer deductions and a wider tax base, individual income taxes as a percentage of GDP remained relatively flat at 7.7% in 1986 and 7.8% in 1988).

And notably, this 1986-style tax reform – where the tax base is widened and/or deductions are eliminated to the point that we don’t need to raise marginal tax rates and in fact can lower them – is the same approach that has been advocated in recent years as well. For instance, the bi-partisan Simpson-Bowles proposal from President Obama’s Deficit Commission suggested reform that would eliminate most tax deductions, expand ordinary income treatment to capital gains and dividends, but reduce the tax brackets down to a simple three-bracket system with rates of 9%, 15%, and 24% (with a top rate possibly as high as 27% if some deductions are kept), resulting in a dramatic decrease in marginal tax rates for most taxpayers. Similarly, the more recent proposal from Republican Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp would also limit most itemized deductions, and reduce down to three tax brackets (10%, 25%, and a top 35% rate that applies for married couples over $450,000 of income), which would reduce marginal tax rates by less than Simpson-Bowles but still to a material extent.

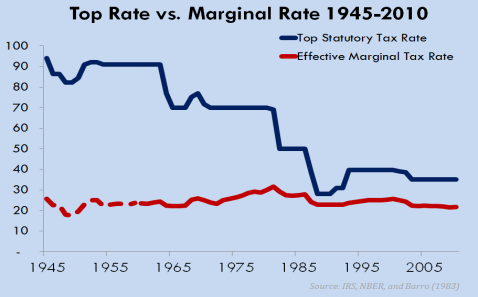

In addition, to the extent that tax reform even does touch the marginal tax rates and increase them, it doesn’t necessarily impact everyone. While it is often noted that the top tax bracket was as high as 94% in the aftermath of World War II, the reality is that tax rate hardly applied to anyone or any income, due both to the incredibly high bracket threshold (it would have taken almost $2.5M in today’s dollars to have been subject to that rate) and also because the structure of deductions and exemptions were very different back then (something we ultimately sought to stamp out by creating the Alternative Minimum Tax 20 years later). For instance, the chart below (based on data from the National Bureau of Economic Research and the Journal of Business) shows the top marginal tax bracket going back to World War II, along with the average marginal rate that was actually paid when weighted by the distribution of AGI; as the chart reveals, while the top marginal rate has varied significantly, the income-weighted typical marginal rate has actually been quite stable for most taxpayers.

Other Non-Income-Tax Remedies For Federal Deficits

As both the history of tax reform and the recent proposals show, the assumption that the total tax burden and effective tax rates “must” rise in the future still doesn't necessarily mean that marginal tax rates will be higher in the future. In fact, almost 70 years of tax reform since World War II has persistently shown that our path to higher taxation typically involves widening the tax base and constraining deductions and even lowering the top marginal rates in the process – an approach that is being signaled by most recent tax reform proposals as well.

In addition, the potential for tax reform that results in higher effective but lower marginal tax rates also ignores all the other ways that additional tax revenue can be generated in the future without adjusting the income tax system! For instance, we are one of the few developed nations that does not have some form of Value-Added Tax {VAT} or other national sales/consumption tax (a VAT is similar to a sales tax, but is applied to manufacturers when the product is made, rather than at the cash register when it is sold). If a VAT were to be introduced in the US in the future, the total tax burden that applies to consumers would rise, but (marginal) income tax rates would not; in fact, the introduction of a VAT could even be paired with reform to our corporate or individual income tax system that lowers income tax rates in exchange for the introduction of a VAT. The end result – once again, a greater future tax burden in total doesn’t necessarily mean higher income tax rates on IRAs.

Similarly, the reality is that some of the greatest drivers to our projected future deficits are attributable to Social Security and Medicare, which at this point are primarily funded via payroll taxes that apply to wages but not to IRA distributions. Accordingly, we could “solve” our Social Security shortfall by increasing the payroll tax by 2.72% of taxable wages (effectively taking the Social Security tax rate from 12.4% to approximately 15.1%) and similarly resolve the Medicare shortfall by levying another 1.11% tax on taxable payroll; while these tax increases would have a significant economic impact, and would result in a higher tax burden for some, they would again not lead to higher income tax rates on future IRA withdrawals (as those taxes apply only to employment income).

Dangers Of Converting To A Roth To Avoid Higher Taxes In The Future

As discussed earlier, the fundamental benefit of a Roth conversion (or contribution) is the opportunity to pay taxes now – presuming rates are lower – rather than deferring the tax liability to the future when rates may be higher. In light of this dynamic, it is quite logical to convert/contribute now to avoid tax rates that may be higher in the future due to changes in tax law… except the reality is that marginal tax rates really might not be higher in the future even if tax burdens increase.

In fact, most current scenarios and proposals - whether it’s the implementation of a VAT, raising Social Security and Medicare taxes, or simply implementing tax reform that pairs together a widening of the tax base and a reduction in tax preferences and deductions without raising tax brackets - are actually paths to lower marginal tax rates in the future, even with a higher total tax burden. And if such a scenario were to happen, individuals could actually find that doing Roth conversions and contributions today may actually turn out to have been wealth destructive. Instead, with reform proposals that could lead to higher tax burdens but lower marginal taxes, it may well be that the best possible outcome could be leaving money in tax-deferred accounts, making new contributions to those accounts, and simply waiting and taking the distributions in the future when marginal tax rates are lower!

Realistically, it’s worth noting that tax reform doesn’t seem very probable in the immediate future. Representative Camp’s proposal was essentially marked “dead on arrival” in Congress as soon as it was put forth, and the Simpson-Bowles plan has seen little movement since the report was released in late 2010. At this point, there may be no progress on tax reform until after the next Presidential election, when we see whether one party or another takes the White House and enough of Congress to push through their version of reform (notably, both parties largely agree on the general structure of reform; the primary debate is simply whether the net result should be revenue-neutral, or a revenue raiser).

Nonetheless, it seems likely that at some point, tax reform will come, and whether in the reform itself or as a part of changes to Social Security, Medicare, and/or the introduction of a VAT, there is a strong likelihood that it will involve a greater future tax burden. But it’s crucial to remember that a higher future tax burden does not necessarily mean higher marginal tax rates in the future… and for those who do seek out conversions, at the least be very cautious about doing Roth conversions in the upper 33%+ tax brackets when most tax reform proposals today have a top rate no higher than 27%! But in the end, the best course of action for most IRA accounts may actually be to wait for the tax “increases” to happen, and do the withdrawals or Roth conversions then, when the marginal rate may be lower!

Michael, you raise a good point, but what about RMDs and higher Medicare premiums? If a Roth conversion now would lower Medicare premiums, even if the actual income taxes paid on the conversion now would be higher than on the RMDs later, how does that factor into the analysis?

Elaine,

I’ve written separately about income-related adjustments to Medicare Part B and Part D premiums. See http://www.kitces.com/blog/income-thresholds-for-medicare-part-b-and-part-d-premiums-an-indirect-marginal-tax/

The answer is it’s basically the equivalent of a roughly 1% increase in your marginal tax rate. Which means it’s worth doing something to avoid if you’re right at the margin, but overall not much of an inhibitor to conversions if you’re otherwise saving a much larger tax spread in the future.

That being said, in practice a lot of the best Roth conversion strategies are about harvesting small Roth conversions in lower tax brackets (e.g., 25% and below), in which case you may never even hit the first AGI threshold for Medicare premium adjustments anyway!

– Michael

As usual, your reasoning makes sense, at least for the example you used. If you have someone, though, who is in the 15% bracket now but who will be in the 25% bracket (assuming rates stay the same) when his RMDs kick in, isn’t it pretty clear that Roth conversions up to the top of the 15% bracket are a good idea?

Bill, that’s what I generally advise – conversions to fill up the 10% bracket for sure, the 15% bracket too in most cases. State taxes towards the top of the 15% Fed bracket make it not quite a slam dunk.

Even high income taxpayers occasionally have low income years to do some of this.

Bill,

Yes absolutely. To the extent Roth conversions can be harvested at lower rates now to avoid higher rates in the future, it’s a win.

The point is just that higher rates because you genuinely have higher income in the future (e.g., because you’re allowing an IRA to compound) is different than saying “Oh Congress is going to raise taxes in the future so we’ll all be higher no matter what” which as I show here, isn’t necessarily coherent logic!

– Michael

Mike,

I’m always concerned with the next generation of wealth misusing an inherited IRA and recognizing large chunks of income accidentally. If a client has no intention of spending the asset down to zero, in my opinion, more wealth is preserved by converting. Hopefully, the next generation of people inheriting the money make sound choices, but in practice how often do we see that? I guess it depends on what people are doing with money (stating the obvious I know)

Best,

Ken

You are correct. The value of an inherited Roth is very powerful. Most of our clients do not need or want RMD’s this leaves the next generation in a far greater place.

Ken,

If they’re not going to make “sound choices” and they’re going to blow through the money, then there’s no tax deferral or compounding growth either way?

In point of fact, I could probably make a case that giving beneficiaries “tax-free Roth” is actually MORE of an incentive for them to liquidate and spend irresponsibly, since withdrawals have no consequences. An IRA that will trigger income taxes at least POTENTIALLY makes them think twice about blowing through the money quickly! (Not that I actually advocate this as a reason to leave IRAs vs Roth IRAs, but just extending the logic you put forth here.)

But again, the bottom line is that I still don’t see why you’d deliberately leave the generation LESS after-tax wealth by converting at higher parental rates if the kids were going to be in lower brackets, and AT WORST they “might be irresponsible” and push their brackets up?

– Michael

Michael,

I’m not speaking about the initial owner, who is making sound choices by doing the analysis and leveraging whatever tax advantages they have available. I’m referencing my generation (29), and I’m convinced that they will access the money as soon as they get it regardless of the tax wrapper. For the record I wasn’t referencing the example you gave where the client is already in the highest bracket, rather I was just speaking to some of the dangerous behavioral tendencies we all see in practice.

Ken

Given the unknowns, why not just stick with some tax diversification?

Pat,

Stock markets are unknown, but that doesn’t mean I go long stocks and short stocks at the same time… “just in case”. Yet having IRA (which wins when rates go down) and Roth IRA (which wins when rates go up) is remarkably similar… you cancel the two out and ensure you’ll never have a net gain on tax brackets?

– Michael

It seems to me that have some of each (i.e., traditional/Roth IRAs) will allow for some flexibility in managing taxes, especially if future expenses are not clear. For example, you may be able to withdraw from the traditional IRA up to the 15% Federal rate and then take the rest of what you need in that year from the Roth IRA.

I am usually aligned with your thinking, but must disagree here. Why wouldn’t one convert and recharacterize to the AMT BE point (28%) after the fact. For affluent clients who will not need IRA liquidity, passing this to G2 or G3 is a no-brainer. If the 5 year rule does come to pass, it’s still greatly beneficial for G1 to have a Roth bucket. If the 5 year rule never happens, it’s a tax free annuity for heirs. As for concern about frivolous beneficiaries, just use a trust which also adds asset protection.

Mike,

So you are certain, for a fact, that no human on the earth will ever inherit an IRA and be in a tax bracket lower than 28%?

Certainly, if my clients are leaving a Roth to their children who are doctors and lawyers, convert up to the 28% bracket. Heck, we’ve had clients convert several hundred thousand dollars THROUGH the AMT 28% bracket all the way until they were going to pop back to the 39.6% regular bracket (see http://www.kitces.com/blog/evaluating-exposure-to-the-alternative-minimum-tax-and-strategies-to-reduce-the-amt-bite/ ).

But that’s only specifically because we had a clear reason to believe the heirs will be in a higher tax bracket in the future. Not as a ‘default’ recommendation that risks blowing up 13% of the value of the IRA if they convert at 28% and leave the account to heirs who turn out to be at no more than 15%!

– Michael

Mike,

If you run the numbers, even with beneficiaries in lower marginal tax rates, Roth will still prevail. Remember, I stated for affluent families where G1 will not need their IRAs this is a no-brainer. Happy to share our Proprietary analysis with you assuming 28% conversion rate and 20% beneficiary marginal tax rate. Just e-mail me best address.

Mike

Michael S. Rubin

Managing Director, Director of Client Tax Services

Bessemer Trust

100 Woodbridge Center Drive

Woodbridge, NJ 07095-1191

t: (732) 694-5768 | f: (212) 408-9665 | e: [email protected]

http://www.bessemer.com

Mike,

Would welcome your email. You can see my contact details at http://www.kitces.com/contact

Mike,

It’s worth noting that I have written that there ARE other factors that drive the outcome of a Roth conversion beyond just the tax rates. See http://www.kitces.com/blog/roth-vs-traditional-ira-the-four-factors-that-determine-which-is-best/

The caveat is just that the tax rates are the overwhelming dominating factor. Most of the others win “all else being equal” but a change in tax rates of just a few percent can be enough to swing the balance the other way. Which can be as simple as G1 in California bequeathing money to G2 in Texas (where the state tax rate differential alone causes the Roth to “lose”).

– Michael

Hi Mike,

While your case has merit, I have a couple of things to point out.

First, even if someone pays 40% tax to convert, it could be worth it if they are in a situation where estate tax kicks in. Suppose a client converts a $1,000,000 IRA and pays $400,000 in income taxes from a taxable account. If the person were in the world of having to pay estate taxes on that money, wouldn’t that effectively reduce the net tax rate from 40% to somewhere closer to 20% since half of the $400,000 would have gone to pay for estate taxes if it were not used to pay for the taxes on the conversion? If the beneficiaries of the Roth are in the 25% marginal tax bracket, then it should be a tax favorable situation to convert.

Second, in your example, you say, “earns $350,000 of ordinary income” and “3.8% Medicare surtax on net investment income.” After reading your paper on Planning for the New 3.8% Medicare Tax on Investment Income, I thought that there would be no NIIT if all of the income was ordinary. Isn’t that true?

Thanks for another point of view.

Jim

Jim,

You’re forgetting the IRD deduction, which provides an INCOME tax deduction to beneficiaries based on the estate taxes caused by the pre-tax IRA. It makes this transaction a wash. You can pay the income taxes first to reduce your estate tax, or pay the estate taxes first and take the IRD to reduce your income taxes, but it comes out the same. That’s literally the point of the IRD deduction; to equalize the two.

Notably, IRD is only at the Federal estate tax level, though. At the state level, your strategy absolutely works. With the caveat that if you boost INCOME tax rates too much, you may find it was better to “just” pay a state estate tax that caps at 16% in most states!

– Michael

Hi Michael,

Excellent point. The feds should clean up the tax code to make this easier to figure out. The always seems to be a caveat. Thank you for your reply and explanation.

With the IRD deduction, you then have to determine if the beneficiaries (potentially kids or grandkids) will itemize their taxes or not, right? Then, you have to keep track of the deduction amount until it is used up. I would assume that you wouldn’t have to use all of the IRD deduction in one tax year, kind of like capital loss carry-forward.

It seems like that could be quite a mess.

Jim

Jim,

Yes, the IRD deduction is contingent on the kids itemizing in the first place (although the dollar amounts involved are often large enough that the IRD deduction alone makes it more-than-worthwhile to itemize). The deduction is claimed as the distributions are taken, so yes if the beneficiaries stretch the IRD deduction too will ‘stretch’ along with it.

– Michael

Michael, you didn’t address the likelihood of a surviving spouse being bumped to a higher marginal tax bracket by virtue of filing status changing from married-filing-jointly to single.

Very good point here and helpful to me as I think through my own Roth conversion strategy. One important technical point, the red line in your graph above should be labelled “Effective average rate” rather than “Effective marginal rate.” It is also worth noting that senior citizens face many implicit marginal tax rates not reflected in the blue line in your graph. The blue line just captures the statutory bracket rates, but there are additional implicit marginal taxes due to the way Social Security is taxed, Medicare income related pricing, and senior citizen income-tested property tax exemptions, just to name a few.

Economist,

Indeed, I’ve written extensively about the other marginal tax rate adjustments that can impact retirees. It was too much to fit in here. The basic principles of Roth conversions are still the same, but yes there are many more, including:

– Social Security taxation as a marginal tax bracket increase: http://www.kitces.com/blog/the-taxation-of-social-security-benefits-as-a-marginal-tax-rate-increase/

– Phaseout of premium assistance tax credits: http://www.kitces.com/blog/how-the-premium-assistance-tax-credit-for-health-insurance-impacts-the-marginal-tax-rate/

– Income-related adjustments to Medicare premiums: http://www.kitces.com/blog/income-thresholds-for-medicare-part-b-and-part-d-premiums-an-indirect-marginal-tax/

– Phaseout of the AMT exemption: http://www.kitces.com/blog/evaluating-exposure-to-the-alternative-minimum-tax-and-strategies-to-reduce-the-amt-bite/

– IRA withdrawals indirectly triggering 3.8% Medicare surtax: http://www.kitces.com/blog/how-ira-withdrawals-in-the-crossover-zone-can-trigger-the-3-8-medicare-surtax-on-net-investment-income/

For a broad (though not “all-inclusive”) chart of factors impacting Marginal Tax Rates with the associated thresholds, see http://www.kitces.com/marginal-tax-rates-chart-for-2014/

Respectfully,

– Michael

Thanks for the very helpful links. Your MRT threshold chart is a very nice and particularly succinct presentation. One additional consideration not mentioned in the links above (which is very much a YMMV issue, since the exact formulation depends on state and local laws, which vary all over the map) is that qualification for senior citizen property tax breaks may be conditioned in some way on AGI. Many retirees in locations with high home values and correspondingly high property taxes pay more in property tax than in income tax, sometimes far more, so this can be a major consideration. Of course, once again this consideration requires a very highly individualized analysis, since there may be a prospect on the horizon of downsizing one’s home and/or a need/desire to relocate to another state near one’s children, where property values/taxes may or may not be lower or applicable senior citizen property tax laws may differ.

It hits me that we as advisors must know the marginal and effective rates of out clients in their Three Phases of Taxation –

– While Working

– Initial Retirement – Before RMD

– Retirement After RMD

Along with what it does to the taxation of their Social Security receipts (a relatively minor factor) and Medicare premiums (still a relatively minor factor ?).

We keep running into this when counseling clients concerning taking a lump sum vs a rollover to their IRA.

Michael,

what are your thoughts on the impact of a conversion on non-tax-deductible

IRA contributions made between conversion and retirement. If one can’t deduct IRA contributions, and has a large Trad IRA, there is almost no reason to make more IRA contribution (no

deduction, so might as well just put it into a taxable account, and any indirect Roth contributions would be taxed on a trad-to-roth ratio). If one doesn’t have a large Trad IRA, contributions can be made to a Roth (indirectly), and that money will grow tax-free. How would you analyze this scenario?

Academics have modeled this, tax rates would have to rise by politically infeasible levels to cancel out the IRA/401k/etc benefits for typical income folks. Few of the raging arguments about Roth vs non-Roth seem to grasp money goes in at highest marginal rate, but comes out at much lower effective rates. Seems to be little realization much of the value of qualified tax accounts is their income averaging aspect. As I recall, their original 1970s intent was to permit higher income professionals to defer taxes, or allow tax leveling.

Stevie,

Given that a Roth vs traditional decision has flexibility, the proper analysis is marginal now vs marginal later. Effective rates are not part of the picture, because they’re formed by a base of income items that will be there REGARDLESS of the To-Roth-Or-Not decision (i.e., you can’t change Social Security payments, pensions, passive portfolio income from taxable accounts, etc.).

Marginal now vs marginal future. Recognizing that tax bracket alone is a terrible estimate of marginal tax rate (now or in the future). See https://www.kitces.com/blog/how-to-evaluate-your-clients-current-and-future-marginal-tax-rate/

– Michael

You say the following:

“If your tax rates are higher now and will be lower in the future, keep

the pre-tax account and wait and withdraw at those lower future rates.

If your tax rates are lower now and will be higher down the road,

convert/contribute to the Roth and pay the tax bill now at the more

favorable rates. I was just wondering about one thing.”

If the latter applies and you say it makes sense to convert, then what about the effect of present value of money? To what extent does paying the taxes now make sense? What if, upon commencing retirement someone paid all taxes converting all pre tax assets into a Roth vehicle and eventually lived 25 to 30 years in retirement. Isn’t it preferable to pay those taxes over a longer period, having use of those funds devoted to taxes that were expended 25 to 30 years ago.