Executive Summary

There are numerous factors that every advisor must consider when objectively assessing a client’s risk tolerance. And if the concept of risk wasn’t already complex enough (as it considers a multitude of facets, including tolerance, capacity, composure, perception, and literacy), the variety of available tools to measure risk tolerance – from written questionnaires to various FinTech software tools and simply having the advisor-client “risk conversation” – often results in inconsistent (or even contradictory) results (especially given that clients vary in their own risk literacy to navigate such assessments in the first place).

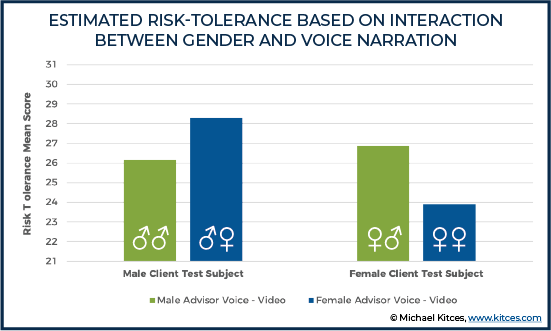

In addition, recent research reveals that the modality of the risk tolerance assessment process can itself influence the results. For instance, one study found that when advisors verbally discuss risk tolerance with clients of the opposite sex, the client’s self-reported risk tolerance tends to be higher than if the client would have responded to an advisor of the same sex. This implicit gender-bias behavior is thought to be driven by subconscious psychobiological tendencies of the client, possibly influenced by a desire to appeal to a person of the opposite sex (even if not otherwise attracted to or interested in them).

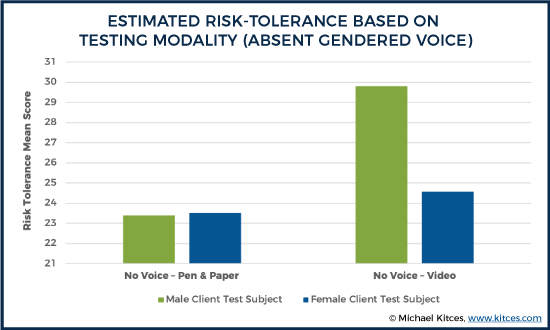

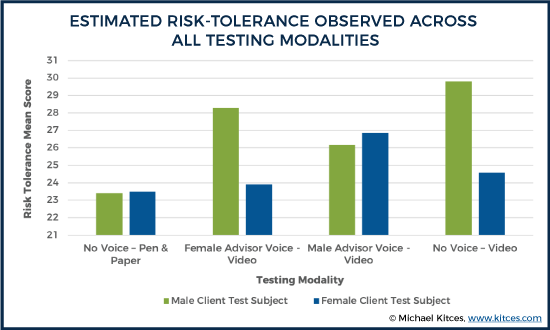

In turn, alternatives to the conversational approach to risk tolerance – such as using pen-and-paper written questionnaires, or FinTech-based software tools for assessment – also appear to have an influence on the results. For instance, while scores for men and women were equal in a pen-and-paper assessment, men scored significantly higher than women in a technology-based video assessment that included the exact same questionnaire as the pen-and-paper test. And although it might be tempting to conclude that the pen-and-paper assessment is better for eliminating the gender gap between men and women, studies have shown that an inherent difference in risk does indeed exist between the sexes, where men generally report higher risk scores than do women. Given that this gender difference was preserved in the technology-based assessment suggests that perhaps gender-neutral technology-based assessments may have the edge over pen-and-paper assessments in most accurately assessing clients’ risk tolerance levels.

On the other hand, it’s also important to recognize that not all technology tools are similar for assessing risk tolerance. In practice, risk tolerance software can be best leveraged by understanding the methods used to measure risk tolerance and also by knowing how risk literate clients are, as certain assessment modalities may resonate more for clients depending on their risk literacy levels. For instance, clients who are highly risk-literate may relate better to econometric measuring technology, such as the software platform provided by Riskalyze. Other less risk-literate clients may relate better to FinaMetrica, another software platform that relies more on psychometric criteria than economically complex quantitative risk trade-offs.

Despite the advisor gender bias observed in risk tolerance studies between men and women and the appeal of gender-neutral technology risk measurement tools that are readily available, conversations with clients should not be eschewed altogether. Instead, they may be effectively used after a (software-based) risk tolerance assessment has been administered, and perhaps by a team of male and female advisors, not only to review the assessment with the client and help them understand the results, but also to supplement the process with a human element involved in helping clients improve their overall risk literacy. Because technology tools are still no match for a person-to-person connection for an advisor to gather the subtle nuances about their clients that software programs are simply unable to detect.

Ultimately, the key point is that there are many factors affecting how clients perceive their relationship with risk, and at least some of these are subconscious influences on human behavior. And as technology-based assessment tools may minimize a client’s bias that can arise in response to their advisor’s gender (while leaving the inherent gender gap that exists between men and women intact), connecting through conversations in person (after the technology-based assessment is administered!) is still the best way to grow relationships and develop trust with clients.

Risk essentially embodies the parable about the blind men and the elephant, in which a group of blind men, who have never encountered an elephant before, each touch different areas on the elephant’s body, yet are unable to discern what an elephant actually is, based on the single part they each have touched. Similarly, risk has many facets, including tolerance (aversion), capacity, perception, composure, and literacy, that are each seemingly discrete but that make up a larger, complex whole.

Risk also has varied measurement concerns – from the type of test (psychometric tests versus econometric tests, and single-item measures versus scales) to the reliability and validity (or lack thereof) of the test one has chosen. Moreover, given that advisors must still address the “elephant in the room”, as the SEC and FINRA both instruct investment advisers and brokers to collect relevant information on their clients (such as giving a risk tolerance assessment) and then use the results of that assessment to create a risk-appropriate portfolio for clients, it is important to get a handle on risk and consider its many facets.

Furthermore, as much as financial advisors and financial researchers try to create and use better tools and practices to address some of the aforementioned concerns – there are still more issues to consider, like how subconscious behaviors in taking risk tolerance assessments themselves, and differences in gender, impact risk tolerance scores and interpretations of them.

Advisor Gender Can Skew Risk Tolerance Assessment Via Verbal Client Conversations

As advisors know, risk is a difficult concept to untangle when working with clients. Which lends itself to a more conversational approach to assess with clients, where advisors have conversations with clients to better understand how the client feels about risk (and in some cases, to help the clients better understand their own risk preferences). Often, these conversations are also beneficial in helping the advisor evaluate the riskiness of the client’s own goals as well. Yet, even with these benefits, it is still important to know that there are lurking caveats.

The “narrator effect” is one such caveat that can skew a client’s self-reported risk tolerance. The narrator effect is commonly found in marketing research, and is simply the (sometimes) subtle authoritative influence that comes through voice (i.e., imagine the impact of a narrator’s voice in a commercial). For example, as is seen in marketing and advertising, female voices are customarily used to sell products geared for women, and male voices are often used for promoting products to men.

So what does the narrator effect have to do with risk tolerance assessments? A lot, as it turns out. In fact, a research study by Dr. John Grable and Dr. Sonya Lutter (née Britt) showed that when advisors discuss risk tolerance with clients, the sound of the advisor’s voice, and more importantly the gender implied by the advisor’s voice, influenced how the client responded. And, again, this is especially important, as many advisors do conduct verbal conversations with clients to gauge their risk tolerance levels.

Specifically, in the experiments conducted by Grable and Lutter, participants were given the same risk tolerance test (the Grable & Lytton Risk Tolerance Scale) and were randomly assigned to one of four conditions:

- participants received a paper-pencil risk tolerance test (control group with no video);

- participants watched a video with a female narrating the risk tolerance test;

- participants watched a video with a male narrating the risk tolerance test; or

- participants watched a video with no narration.

The results showed that when participants heard the voice of an advisor of the opposite sex, the participant reported higher-than-average risk tolerance for their gender. In other words, women reported higher risk tolerance in response to a male asking the assessment questions, and vice versa for men responding to a female (vs. male) questioner. In addition, women’s scores increased more dramatically in response to the male voice, when compared to the men’s scores in response to the female voice (relative to hearing the voice of their own gender).

The key point from this experiment is that, for both men and women, the gender of the advisor’s voice asking risk tolerance questions can dramatically impact a person’s reported comfort with risk in their portfolio.

Gender Matters Because Of Subconscious Biases

So, what is driving this behavior, where the gender of the advisor actually influences the client’s responses to a risk tolerance questionnaire? We do not know for sure, but there is some research to look to.

For instance, the mixed-gender issue could partially be explained by biological factors. Research by Jones, Feinberg, DeBruine, Little and Vukovic (2010) propose the idea that humans are subconsciously biased to respond to messages that are delivered by different voices, influenced by a subconscious desire to appear more attractive to the opposite sex. And while it might seem dubious that our perceived risk tolerance is as impressionable to change as it is, simply from the sound of a person’s voice, research has been done identifying an evolutionary basis for many of the psychological phenomena that advisors see clients display in financial planning relationships.

That being said, this biological framework does not suggest that, in opposite-sex client-advisor relationships, advisors or clients would knowingly or actively try to appear more attractive to each other. Yet, being that many behaviors are subconscious and susceptible to influence by one’s sex and gender identity, we may not always understand or be fully aware of the biological forces that affect our decisions – and that they may be impacting the way we perceive our own risk tolerance under different circumstances.

The Modality Of A Risk Tolerance Assessment Can Remove Gender Bias – Which Is Not Necessarily A Good Thing

Because undue gender influences that arise during advisor-client conversations can unintentionally skew a client’s self-perceived risk tolerance, advisors might seek to find more objective methods to discover a client’s attitudes about risk. Fortunately, the work conducted by Grable and Lutter (indirectly) found out that testing modalities actually can eliminate gender bias – as the control group used in their study, in which members were given only a pen-and-paper test, showed that cross-gender bias (male voices for female clients and female voices for male clients) was eliminated. In other words, male and female test subjects indicated virtually identical risk tolerance scores when taking the assessment, without any gender-biased “narrator effect” to influence their responses!

However, while it might seem like a good thing that gender bias appears to have been removed through the pen-and-paper testing modality, it is important to note that this test modality essentially removes the gender gap that should be there. This expected “gender gap”, surprisingly absent from the pen-and-paper test results, is a well-documented finding across numerous risk assessments.

For example, research studies using the Grable and Lytton risk tolerance scale have found a consistent difference between the risk tolerance reported by males and females. This inherent gender gap is also seen in numerous studies using the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances, the most useful ‘big data’ set used in financial planning, which show that women tend to have a lower financial risk tolerance compared to that of men.

Another example of gendered risk tolerance observed by financial planners is found in research by Hallahan, Faff, and McKenzie (2004) using the Finametrica dataset, where female investors scored significantly lower than male investors in terms of tolerance for financial risk. This finding held true even when controlling for other relevant demographic factors (e.g., marital status, income, etc.).

The key point here is that there is a consistent and well-documented gender gap in risk tolerance – regardless of why it exists, or whether it’s good or bad – and that this gap is expected to be observed (and should be reflected) in a study that employs valid risk tolerance assessment methodologies.

Importantly, though, because the anticipated gender gap does not exist with the pen-and-paper testing modality, it implies that this test result is actually somehow ‘abnormal’, and that the testing modality once again really does matter (voice vs. pen-and-paper, and now no voice/technology vs. pen-and-paper) in potentially impacting the way a client responds in unique ways, depending on the client’s gender.

Technology Best Assesses Risk Tolerance Without Gender Influence, Leaving The Expected Gender Gap Intact

The good news in all of this is that there is a third option: Technology. Technology can potentially provide a means of risk tolerance assessment without any risk of gender bias that might result from conversations between an advisor and client, and at the same time has been shown to retain the inherent gender gap we expect to see (and that we tend to actually see in all studies) between men and women. In other words, it may offer the most objective approach to gathering risk tolerance information.

For instance, as seen in Grable & Lutter’s work, men using technology for risk tolerance assessment – a video, but without any (potentially-gender-biased) voice narration – reported much higher levels of risk tolerance than women, and even surpassed the results found when compared to all other testing modalities. (Potentially because, as other research has documented, men tend to be more responsive to visual (versus verbal) communication).

Conversely, women, using the technology-based assessment with no narrator voice reported a much smaller increase in risk tolerance relative to pen and paper, compared to the large difference in risk tolerance score observed in men.

Still, though, the tech-only approach must be evaluated with a careful eye, because it may tend to potentially tilt clients (especially men!) towards more aggressive portfolios; however, it does appear to do so in the most neutral manner without advisor gender impacting the results, and at the same time it preserves the previously researched and expected inherent gender bias.

How Advisors Can Use Technology To Assess Risk Tolerance Objectively and More Consistently (But Shouldn’t Eschew The Conversation Entirely)

So what can be done with all of this information? There are a few considerations that advisors and their firm may wish to consider.

Technology Improves The Results, But The Best Tech Tool Depends On Client Risk Literacy

Recognizing how a firm’s use of risk tolerance software impacts clients is a good first step, but is most effectively done with an understanding of clients’ risk literacy levels as well. Risk literacy is essentially the ability to understand the technical aspects of risk, and to use that understanding to make informed decisions. And this is important, because clients with different levels of risk literacy will benefit from different styles of discussion around risk. As while clients with high risk literacy levels may be more receptive to a discussion oriented around technical details and complex economic trade-offs (that they have the risk literacy to properly evaluate), a client with lower risk literacy may relate better to a discussion that focuses more on behaviors and goal setting.

For instance, Riskalyze is an econometric measurement tool involving more quantitative analysis than behavioral assessment and might best be used with clients with high risk literacy. If clients do not have high risk literacy, it may still be feasible to use econometric methods to assess their risk tolerance, but clients can be confused by the assessment instructions and may need some guidance during the assessment. Follow-up conversations pertaining to the client’s responses can also be important for the client to understand the results and benefit from the assessment.

On the other hand, Finametrica is a psychometric measurement tool and focuses more on personality and behavioral traits of clients. This assessment appears to more accurately account for real-world risk-taking behavior, and while this type of assessment technology can be suitable for clients regardless of risk literacy levels, it still never hurts to discuss the results before moving forward and actually developing a portfolio.

What is more, simply knowing that different tools address different aspects of risk, it may be worthwhile to use more than one assessment modality. The Grable and Lytton risk tolerance scale is a psychometric measure (downloadable here) that advisory firms using Riskalyze, or other econometric measurement tools, may want to incorporate.

Using Technology-Based Risk Tolerance Assessments To Standardize And Avoid Unwitting Conversational Advisor Biases

Another step to develop a more objective and consistent process is to consider creating a firm-wide risk tolerance assessment approach that standardizes the use of risk tolerance technology with clients, along with a set of guidelines on how to discuss assessment results with clients. Using technology removes the advisor-gender voice bias concerns and generally makes it much easier for firms to standardize the risk tolerance assessment process across the firm. Which can further reduce the risk of advisors unintentionally introducing their own preferences or biases in a purely conversational approach – and according to some research is a prevalent (and serious) problem.

For instance, research conducted by Grable and Hubble found that advisors using the conversational approach can tend to measure risk tolerance inconsistently – given one single client, different advisors generated significantly different portfolio designs for that client, “ranging from a risky 85% in stocks to a timid 100% in bonds. They also suggested wildly divergent holdings for clients who had identical circumstances but slightly different risk scores.”

These findings are further supported by another study, conducted by Michael Roszkowski, John Grable, and Justin Hall, suggesting that advisors were generally unable to subjectively determine a client’s risk tolerance, and were in fact no better than non-professionals at guessing a client’s risk tolerance based on a conversation about their risk preferences.

And not only do advisors (without the appropriate tools) have a hard time objectively measuring a client’s risk tolerance, they might also (subconsciously) be subject to their own overconfidence bias that can interfere with results. Research conducted by Markus Glaser, Thomas Langer, and Martin Weber found that financial professionals, like non-professionals, can fall prey to this. For example, an advisor might believe that some of the risk tolerance tools used by their firm can provide inaccurate results; because of this, they may not trust the scores, and may instead disregard some (if not all) of the results, substituting their own experience and knowledge to build a portfolio for a client. Even though the client’s own risk tolerance didn’t merit such a portfolio in the first place.

Another caveat is highlighted in research published by Dr. Stephen Diacon, which suggests that financial professionals tend to have a higher risk tolerance than the average client, and that financial advisors tend to be less loss averse when compared to clients.

Taken together, these examples emphasize the importance of using technology tools to remove the various biases that financial advisors can be prone to (simply for being human), and to provide an objective, and standardized assessment of clients’ risk tolerance.

For advisory firms that still want to build primarily on a conversational approach, another alternative is to deliberately ensure that advisor teams have a combination of male and female advisors, to potentially reduce the advisor-gender voice bias. Working in advisor teams has become a very popular way to service clients, and including both a male and a female advisor in a team (and ensuring they both participate in the conversation) just might help clients answer more truthfully in line with their actual risk perspective. (Although research has not been done to confirm that having a male and a female in the room would counteract the potential subconscious biases, it probably wouldn’t hurt!)

Wrapping Up Technology Assessments With Follow-Up Conversations

As great as it is, it’s important to recognize that technology alone won’t reveal all the nuances of a client’s attitudes and beliefs about risk. And having follow-up discussions to talk through the scenarios introduced by technology tools can actually help clients further process their understanding of risk.

Accordingly, it’s still good to have conversations that supplement the technology-driven risk tolerance questionnaire process. Not to mention that talking with clients can develop their risk literacy and broach other aspects of risk, such as composure (how stable a client’s perceptions are of the risks in the marketplace) and capacity (how much risk a client can actually afford to take).

So, talk with clients …but only after they have taken the (technology-based) risk tolerance assessment first!

Ultimately, the bottom line is that there are many factors affecting how clients perceive their relationship with risk, and at least some of these are subconscious influences on human behavior. Gender bias, for example, is one such factor – research by Grable and Lutter shows that male and female clients both perceive their risk tolerance to be higher when responding to assessments given to them by advisors of the opposite sex, in comparison to how they respond to assessments conducted by advisors of the same sex.

Yet the fact is that gender gaps really do exist – there are real differences between men and women that go beyond physiological traits – even without the gender of the advisor’s voice amplifying the effect. Whether the gender differences seen in risk assessment results emanate from biological factors or social influences is unclear; the important point, though, is that there are gender differences, and the optimal risk tolerance assessment approach should be able to properly identify them.

Accordingly, it’s important to recognize how testing modalities influence the way clients perceive their risk tolerance. As while the conversational approach introduces a gender bias from the advisor’s voice, pen-and-paper risk assessments have been shown to avoid the gender bias potentially introduced by an advisor in conversation (but at the cost of also eliminating the gender gap differences between men and women that should be there), which in turn are restored with computer-based risk tolerance software.

Importantly, though, actual conversations with clients should still be conducted, because technology alone can’t capture all of the nuances of a client’s attitudes toward risk, and it certainly can’t replace the value of connecting with clients on a human level to develop strong relationships built on empathy and trust

Throughout my career of 30 years, I’ve only used “risk tolerance” as one aspect of what might influence both my recommendations and my approach in “handling” my client. What I have found more compelling is to put risk into the larger context of need. What does you money have to do for you in order to meet your goals or needs. I’ve become dismayed by the regulatory fixation upon defining emotion and yet never once referencing financial need. I’ve just left a broker dealer and moved my practice to an Active Portfolio Managed approach using ETF’s. We are conducting a series of taped KYC conversations between the PM, the client and I, in which the PM asks the Regulatory questions and I contribute the return requirements imputed in the plan. This more holistic approach to risk has led to better “risk” conversations and a fuller understanding of how the accounts should be managed and ultimately invested. As your article points out emotions are fickle and notably influenced by gender, process, form and context.

I’m still holding out for the risk assessment tool that crunches 10 years’ worth of actual, aggregated financial transactions to generate a risk profile of each household.

No more asking clients “what would you do” kind of questions: this tech would be able to determine what households *actually did* with their cash flow (how much in fixed expenses have you targeted in your household?), debts (how much leverage are you actually comfortable holding over a period of time?), and investments (how much of your income have you been willing to set aside for the long term?) over a decade.

I won’t hold my breath, though, because I’ve been waiting for this technology for the last 10 years…

While not exactly what you’re referring to, Dr. Daniel Crosby and Brinker Capital are developing a more simulation based risk tolerance assessment tool (vs. the traditional questionnaire) that I think would provide much of what you’re referring to. Even more impressive, once the scenario has been run by the client it will be able to proactively alert advisers of clients who may be at risk for irrational responses based off real market conditions and the client’s cataloged specific behavioral responses. Check it out: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lWk71M7hTEI. Given the lack of any real volatility in the last 10 years, the simulation may provide more informative data anyway…

“lack of any real volatility in the last 10 years?”

June 2010: Flash crash

September 2011 to June 2012: European sovereign debt crisis

October 2013: Government shutdown concerns

August 2015: China’s economic slowdown fears

February to June 2016: Brexit announcement and vote

January 2018: Government shutdown concerns (again!)

February 2018: Bond market selloff fears

December 2018: Federal Reserve political independence concerns

That’s at least eight periods of heightened volatility in domestic and global stock markets, not including the residual volatility immediately after the Great Recession of 2008-2009.

So again, I want to go get actual transactions from investor accounts during those periods. Did investment purchases stop anytime? If so, when, and when did they resume, if at all? Did some investors never change their investment patterns? Did some investors sell equities and buy bonds & cash equivalents? Did other investors increase the volume and/or frequency of their buying?

And on the household level, did some households pay off short- and long-term debts? Did other households add to their debt levels? How thin did some households run their monthly income vs expense ratio? Did some move more discretionary income into investment accounts? Did other reduce funds directed to investment accounts and instead accumulate cash?

This is the evidence I think many behavioral economists would find extremely useful and insightful, but I’m afraid none of the transaction data providers are willing to hand over such data without some soft of exorbitant price (or rather, ransom) attached to it.

VERY INTERESTING STUDY OF GENDER VOICE BIAS ALONG WITH TECHNOLOGY vs PEN & PAPER. CERTAINLY WE HAVE TO TAKE INTO ACCOUNT THE CLIENT’S KNOWLEDGE OF RISK AS WELL AS THEIR EMOTIONAL REACTION TO RISK SCENARIOS ALONG WITH THEIR TIME HORIZON FOR THE LIQUIDITY OF THE FUNDS. MOST CLIENTS ARE NOT AWARE THAT A LOSS OF 20% WILL REQUIRE A 25% GAIN TO GET EVEN. A 25% LOSS REQUIRES 33% TO GET BACK TO EVEN. THESE CONCEPTS ARE IMPORTANT DISCUSSIONS TO SHARE WITH CLIENTS. FEW WANT EXPOSURE TO 2008 MARKET DOWNSIDE.