Executive Summary

For prospective and current retirees who are concerned that "unexpected" or extreme longevity may lead them to run out of money, there are few strategies more effective than the decision to delay Social Security benefits. The tradeoff - where payments are not received now, in exchange for higher payments in the future - is similar to buying an income annuity, or investing in a bond ladder that will begin liquidating in the future... except that the implicit "pricing" of the decision to delay Social Security is far better than any commercial annuity or bond yields available today.

The caveat to the approach, however, is that Social Security dependent benefits may also be available for those in their 60s who still have young children in the home - an increasingly common situation, between couples who start a family later and the rising divorce rate that has also led to a greater frequency of second marriages with young children. And the availability of dependent's benefits can significant diminish the benefit of delaying Social Security; while delaying does increase the individual's own benefits in the future, along with potential survivor benefits, waiting may also permanently forfeit children's benefits that won't be available down the road (as the children may be too old by the time the retiree reaches age 70).

In light of this situation, planning for Social Security benefits with "young" children in the home (those under age 18) needs to be done more carefully. In some situations, the children may be so close to 18 that it's still worthwhile to delay. In other scenarios, the opportunity to file-and-suspend at age 66 - starting both spousal benefits and activating dependent benefits as well - may be the best way to go. But in many situations, the potential dependent and spouse's benefits are so large - even with the "maximum family benefit" limitations - that the best strategy, even in the long run, is to start benefits as early as possible (especially if the Earnings Test will not apply!).

(Michael's Note: Some Social Security claiming strategies discussed in this article have been materially impacted by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, which has eliminated most forms of the File-and-Suspend strategy. See "Congress Is Killing The File-And-Suspend And Restricted Application Social Security Strategies" for further details.)

Social Security Dependent Benefits For Children And The Maximum Family Benefit

When someone is eligible for individual retirement benefits under Social Security, it is also possible for his/her dependent child (including biological children, [legally] adopted children, and even stepchildren) to receive payments as well. To be eligible, the child must be unmarried and under the age of 18 (if still in high school, the child is eligible until graduate or two months after turning age 19, whichever comes first). Children over age 18 are also eligible if they are disabled, with no upper age limit, as long as the disability started before the age of 22. The dependent child benefit is equal to 50% of the unreduced benefit the parent would receive at full retirement age (i.e., their Primary Insurance Amount or PIA), which means even if the parent starts early (reducing their own benefit) the child’s benefit remains the same.

Notably, a spouse who is under age 62 is also eligible for a spousal benefit under these rules, as long as the spouse is a parent caring for a qualifying child who is under the age of 16. Given this age threshold, it’s notable that the young spouse’s parent benefit will end earlier – by age 16 – than the dependent child’s own benefits, which lasts until 18.

If there are multiple children, each child is eligible for a dependent child benefit – in addition to a potential spousal benefit – but the total benefits paid under one person’s earnings record are limited to a maximum family benefit that varies from 150% to 180% of the PIA. To the extent that total family benefits – including the retiree and dependent children, as well as any spousal benefits paid based on the retiree’s worker record – exceed this maximum, the share of benefits for the spouse and dependent children (also known as "auxiliary benefits") will each be reduced proportionately until brought down to the family maximum threshold.

Example. James is eligible for a $2,000/month Social Security benefit at full retirement age. In addition, he has two young children and a younger spouse who would each be eligible for benefits (of $1,000/month each). James’ maximum family benefit under the 2014 formula would be approximately $3,478, of which his own benefit takes up $2,000/month. As a result, the remaining $3,478 - $2,000 = $1,478/month will be divided evenly amongst his two children and spouse, for auxiliary benefits of (only) $492/month. If one of the children turns 18, such that she is no longer eligible, the $1,478 will then be reallocated evenly amongst the two remaining beneficiaries (assuming both are still eligible) and their benefits will be adjusted up from $492/month to $739/month.

To be eligible for dependent child benefits, the worker-now-retiree must actually apply for his/her own benefits as well (similar to the rules for activating spousal benefits, including the young-spouse-as-parent rule). A version of the dependent child benefit also applies for young children of a deceased parent, in the form of a child’s survivor benefit.

How A Child’s Dependent Benefits Impacts Social Security Timing Decisions

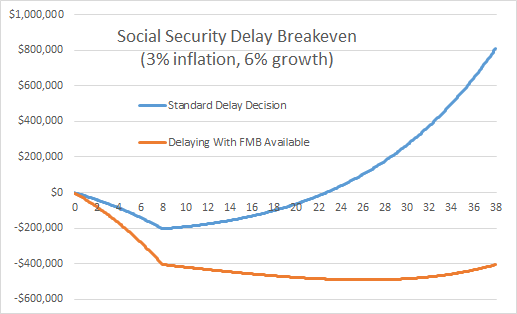

In the “normal” context of deciding when to start Social Security benefits, there is a straightforward trade-off – the individual chooses not to receive benefits now, and in exchange receives higher benefits in the future. Thus, for instance, a retiree eligible for $2,000/month at full retirement age, could choose to take $2,000/month now, or wait a year and forfeit $24,000 of benefits not received in exchange for an extra $160/month (with an 8% delayed retirement credit) starting next year and going every year thereafter. Once adjusting for an inflation rate on the extra $160/month (thanks to cost-of-living adjustments) and a reasonable growth/discount rate on the $24,000, we can determine the “breakeven” period of how long the retiree must live for the trade-off to be worthwhile. The end point – it takes upwards of 15 years just to break even, but the Social Security delay decision can produce an internal rate of return (and especially a risk-adjusted return) superior to available investment alternatives for those who live materially beyond that point. In fact, delaying Social Security is often appealing because the situations in which it works best – unexpected longevity, high inflation, and poor market returns – are the exact scenarios that portfolio-based retirement plans tend to struggle, which means delaying Social Security is an incredibly effective retirement income hedging technique.

However, the situation shifts when there are dependent benefits (or a young-spouse-as-parent) benefit involved. For instance, if we continue the earlier example, assuming James is eligible for a $2,000/month retirement benefit at full retirement age, but has just turned age 62 and is considering whether to take a $1,500/month benefit now (starting 4 years early) or wait until full retirement age to get $2,000/month (or even delay all the way to age 70 and get $2,640/month). In the “standard” scenario, we could weigh this trade-off – James gets $1,500/month now, versus waiting as much as 8 years for a $2,640 / $1,500 = 76% cumulative benefit increase.

Yet if James has 10-year-old twins and a much-younger wife, and the family will be eligible for several auxiliary benefits for the next 8 years, including a spousal benefit and two dependent child’s benefits. As a result, the decision to delay means James gives up not only his $1,500/month early benefit but also $1,478/month of auxiliary benefits for the next 8 years (notably, available auxiliary benefits under the family maximum benefit are always calculated based on James' full PIA, even if his benefits are reduced because he starts early), in exchange for increasing his age-70-and-beyond benefit to $2,640/month. This represents a dramatically higher “cost” to James for considering whether to delay, as the family benefits will be permanently lost (as by the time James turns 70, the children will be 18 and no longer eligible for dependent benefits at all!).

In fact, at the chart above shows, delaying the maximum family benefit digs such a hole and forfeits so much opportunity for portfolio growth (either by failing to invest the family benefits payments that weren’t received, or by being forced to liquidate other investment assets that will no longer be able to grow because there were no family benefits payments to cover spending needs), that the decision to delay never catches up. By the time payments begin, the foregone growth on benefits is so large the gap just compounds wider and wider over time! So while the breakeven period at 6% growth (and 3% inflation) for a standard benefit delay decision is about 22 years (which would be age 84 for someone currently age 62 evaluating the decision), the breakeven period when giving up family benefits is never!

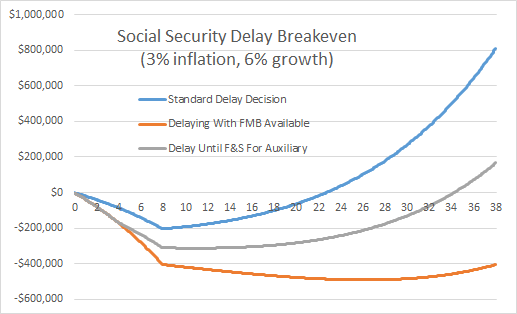

However, one planning opportunity for those considering family benefits is to file-and-suspend, which not only activates spousal benefits but also dependent child benefits. Accordingly, James could actually plan to delay just 4 years, then file-and-suspend at age 66 to activate the spousal and two dependent benefits, and then wait another 4 years for his own benefit at age 70. As the chart below shows, the impact of waiting 4 years is significant, but the “damage” is somewhat mitigated and there is at least some breakeven point (which a much-younger spouse might reach given the potential for survivor benefits!).

Strategies To Maximize Social Security Dependent Benefits For The Family

As the chart above shows, the potential of giving up significant family benefits can turn what may otherwise be an appealing decision to delay Social Security benefits as a hedge against longevity instead an adverse scenario where there is no breakeven to even recover by delaying benefits, or at least a situation where the breakeven is much further out than is typical.

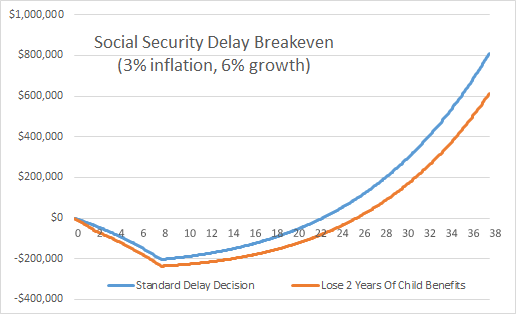

Of course, the example above illustrates the absolute extreme – multiple family members that drive the foregone benefits all the way up to the maximum family benefit, who would have received benefits for exactly the full 8 year waiting period, resulting in the maximum possible “loss” by waiting. However, if the situation is that the age 62 retiree “merely” has one 16-year-old child whose benefits will be lost for just 2 years (from age 62 to 64) while waiting to age 70, the impact is diminished but can still be material and push the breakeven period out several years and require significant expectations of longevity to be worthwhile, as shown below.

While the impact of “just” losing 2 years of benefits for a 16-year-old child can be significant, the impact of losing even partial family benefits ramps up further as children are even younger. For instance, if the child in the above scenario was age 14, the impact would be even more severe, as delaying would forfeit not only 4 years of a child’s benefit, but also 2 years of a spouse’s benefit until the child would have been age 16 (assuming there is a spouse).

On the other hand, it’s worth remembering (as mentioned earlier) that in the situation where there is a much younger spouse, it may still be worthwhile to delay at least a limited time period for family benefits. The reason is that a younger spouse will be eligible for a survivor benefit in the future – which is increased by delaying – and if the couple has a big age gap, the higher benefits as long as the primary earner is alive plus the surviving spouse starting her survivor benefits at age 60 (at some point in the future) will have a very long time window to be able to reach the admittedly long breakeven period. In other words, even a 30+ year breakeven period may be appealing when involves increasing survivor benefits for a spouse who is only 50-something (or even younger) now and really could live and draw on benefits more than 30 years. (Though notably, this in turn is less important if the spouse would have her own retirement benefits from her own earnings record, diminishing how much extra dollars a survivor benefit really provides over what she would get already.)

For those who are already well into their 60s, the most appealing path to coordinating family benefits may be to file-and-suspend at their full retirement age, and/or weigh whether it’s worth waiting until full retirement age just to get the opportunity to file-and-suspend and then further delay to age 70 to increase personal retirement benefits (and future survivor benefits). In this situation, the retiree would still be starting some benefits a little early – at age 66 – but not as early as possible at age 62 (when file-and-suspend isn’t permitted).

Of course, the most important caveat to those considering whether to start benefits early to tap family benefits is the Social Security Earnings Test, where wages or self-employment income above the $15,480/year threshold can not only reduce the worker’s own benefits if started early (the Earnings Test no longer applies at full retirement age), but if the children (or spouse) are working and earning income over the threshold they can reduce their share of the family benefits as well. Obviously, it’s not necessarily helpful to claim Social Security early to generate individual and family benefits if some/most/all of them will be lost due to the Earnings Test anyway. (Again, as with file-and-suspend, this means it might be worthwhile to start “early” at full retirement age, but not “very early” at age 62).

Nonetheless, for those who don’t face the Social Security Earnings Test, the opportunity for dependent child benefits – and potentially a spousal benefit for to support the care for an under-age-16 child – can significantly change what may otherwise be an appealing decision to delay Social Security benefits as a longevity hedge. While the trade-off can be appealing based on an individual’s own retirement (and survivor) benefit, the additional “cost” to delay in the form of forgoing both individual benefits and family benefits can become too high a hurdle for delaying to be worthwhile. To say the least, this means anyone who has under-age-18 children (or dependent adult children who were disabled before age 22) should consider much more carefully whether it’s really a good idea to delay benefits or not, as there may be far more dollars at stake!