Executive Summary

There is a fundamental difference between hiring an advisor and hiring a salesperson. As while both have essential roles in the economy – sometimes we want the advice of a nutritionist about our red meat intake, and other times we simply want the butcher to sell us the best cut of meat – regulation has long recognized the importance of “truth in advertising” when it comes to those respective roles. Simply put, it’s important for advisors to communicate that they’re advisors and for salespeople to communicate that they’re salespeople (and not advisors), lest the consumer receive conflicted advice from a salesperson who isn’t actually trying to advise but simply wants to sell their product. Thus why nutritionists are subject to different rules than butchers, why doctors are regulated in a distinct manner from the drug industry, and why investment advisers are regulated in a different manner than brokers.

In fact, the entire genesis of the Investment Advisers Act – that forms the foundation for the fiduciary regulation of investment advice – was a stated intention by Congress to separate the “bona fide investment counselor” from the “tipsters and touts” looking to sell brokerage products under the guise of advice. Which, notably, didn’t mean limiting broker-dealers from engaging in the sales activities of brokering and dealing – which are foundational to the operation of the stock market and the function of capital formation in public markets – but instead was about separating the activities of advisors and brokers, by applying separate registration requirements for investment advisers, and higher (fiduciary) standards of conduct for those who registered as such.

To maintain this distinction, Congress also included in the Advisers Act under Section 208(c) a requirement that it wasn’t even permissible to use the “investment counselor” title, or to “represent as an investment counsel”, without actually being principally in the business of providing such advice services (and subject to the fiduciary standard that would apply to such advice). In other words, advisors weren’t permitted to advertise that they were advisors unless they agreed to be regulated as (fiduciary) advisors.

Yet in the 80 years since, the titles used to convey advice services have changed substantially, from what was once a relatively ubiquitous title of “investment counselor” to the more modern versions “financial advisor” or “financial consultant” or “wealth manager”. Notably, though, Section 208(c) of the Advisers Act regulates not just the title of “investment counselor”, but also the function of providing “investment counsel” services… which is just as relevant today as it was 80 years ago. Even though, in practice, the SEC does not regulate “financial advisor” titles today the way it regulated “investment counselor” decades ago.

At the same time, the growth of financial planning as a distinct profession alongside investment advice has created new regulatory challenges. In 2005, the SEC recognized this by declaring, similar to Section 208(c) for investment counsel, that those who either hold out as a “financial planner”, offer financial planning services, or deliver a financial plan to the client, cannot operate as brokers and must be regulated as fiduciary investment advisers. Yet when the 2005 rule was subsequently vacated by the Courts – for reasons unrelated to the regulation of financial planners – the SEC stated in a 2007 Proposed Rule that it would ‘soon’ revisit the regulation of financial planning. But 14 years later, the 2007 Proposed Rule is still just proposed.

Accordingly, this week XY Planning Network is filing a series of two Petitions for Rulemaking to the SEC, to take up again the 2007 Proposed Rule and its consideration of whether financial planning titles and services should automatically trigger fiduciary investment adviser registration, and to modernize Section 208(c) of the Advisers Act and better define in today’s environment what constitutes “investment counsel” services that would necessitate not just registration as an investment adviser but a requirement to principally be in the business of advice in order to market one’s services as such.

Because in the end, there remains an essential role for both advice and sales, and consumers should have the choice about whether to engage a salesperson to implement a desired purchase, or an advisor to help them select the right purchase to implement in the first place. But regulation of advice and sales begins with a fundamental truth-in-advertising obligation that advisors and salespeople advertise as such, so the end client understands the nature of the relationship that they are engaging to begin with. And so as the offering of financial advice services evolves, along with the marketing and other titles used to convey such services… it’s time for regulation to evolve with the times as well!

The Origins Of The Business Of Financial Advice And Investment Counsel

For as long as there have been financial services firms selling stocks and bonds to the public, such firms have been in a position to recommend certain such investment securities to their customers, in the hopes of gaining their interest and attention and ultimately their dollars to close the sale.

In fact, it was only in the aftermath of World War I that, alongside an explosion in the issuance of stocks and bonds that individual investors (and not just institutional investors) could purchase – creating an overwhelming number of investment choices and a need for guidance about which ones to invest in – that a new type of service began to emerge, where a subset of professionals began to be hired not just from the brokerage firms and banks that were the primary sellers of stocks and bonds of the day, but hired directly by their clients to receive counsel about which stock and bond investments they should buy.

What was unique about this new crop of “investment counselors” was that they were specifically not paid to effect the sale of a stock or a bond (e.g., to earn a trading commission), and were often not even affiliated with the banks and brokerage firms of the day, instead operating independently and receiving fee compensation for their advice and counsel itself, forming a distinct new type of business model and a substantively different service for consumers… accompanied by the different expectations that emerge for those who are hired to give good counsel and not merely to sell a product.

The challenge, however, was that the banks and brokerage firms touting their stocks and bonds for sale also realized that it was very effective to position their stock and bond sales tips as ‘financial advice’, and began to appropriate the investment counsel title and marketing for themselves. The issue became so problematic in the two decades that followed World War I that in 1935, attached to (otherwise unrelated) new legislation to regulate public utility holding companies, the SEC was also directed in Section 30 of the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 to “make a study of the functions and activities of investment trusts and investment companies” (to understand the influence such pooled investment vehicles may be exerting in the marketplace, including on utility companies).

What resulted was a 1939 study that highlighted how entwined the business of investment counsel had become with the business or bank and brokerage securities sales, recognizing that “the availability of such [an advice] service to investors created an additional incentive to a purchaser… to patronize particular brokers or investment bankers with the resultant increase in their brokerage or securities business,” and acknowledging “the problem [for consumers] of distinguishing between bona fide investment counselors and the ‘tipster’ organizations [selling investment products]”.

In fact, testimony to Congress at the time by the “Investment Counsel Association of America” (ICAA, known today as the Investment Advisers Association), which was formed in 1937 to give an advocacy voice to investment counselors, highlighted how:

"…a great many people held themselves out, as I understand it, as being investment counsel, when actually they had none of those qualifications and…had the entire range from the fellow without competence and without conscience at one end of the scale, to the capable, well-trained, utterly unbiased man or firm, trying to render a purely professional service, at the other end."

And similarly that:

“Some of these organizations using the descriptive title of investment counsel were in reality dealers or brokers offering to give advice free in anticipation of sales and brokerage commission on transactions executed upon such free advice…”

In other words, similar to the debates of today, investment counsels providing fee-only advice services were expressing frustration more than 80 years ago that brokerage firms were similarly representing that they, too, offered “advice” to their customers, even though, in the end, they were merely giving that advice as a means to earn a commission on the subsequent sale!

In response, ICAA advocated that “investment counsel organizations could not completely perform their basic function – furnishing to clients on a personal basis competent, unbiased, and continuous advice regarding the sound management of their investments – unless all conflicts of interest between the investment counsel and the client were removed” (an 84-year-old predecessor to the modern “Fee-Only” approach to objective financial advice!), and it was ICAA that lobbied for a new regulatory framework that would hold them – as investment counselors – to a higher standard given the professional role they played (and distinguishing them from salespeople acting as “tipsters” in the process).

And Congress agreed. What followed a year later was the establishment of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, which the House Committee report outright stated was established “to protect the public from the frauds and misrepresentations of unscrupulous tipsters and touts and to safeguard the honest investment advisers against the stigma of the activities of these individuals…” and took “especial care… in the drafting of the bill to respect [the personalized advice] relationship between investment advisers and their clients” under a fiduciary standard.

Notably, that fiduciary standard itself was left unstated in the original law of the Advisers Act, but confirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1963 decision of the case of SEC v Capital Gains Research Bureau (1963) recognized the “delicate fiduciary nature of an investment advisory relationship”. In that case, the Court went on to state that “the adviser’s fiduciary relationship to his clients requires that his advice be disinterested” because of the “relationship of trust and confidence… between the advisor and the advised”.

Notably, though, when Congress first recognized – more than 80 years ago – that banks and brokerage firms were creeping into the business of providing investment counsel and financial advice in order to sell more of their investment products, the conclusion was not to implement a uniform fiduciary standard for investment counselors and broker-dealers. Instead, the decision was to separate sales from advice, leaving the existing structure of broker-dealers (and their existing standards of conduct) intact, and creating a new category of firm (with a new, higher fiduciary standard of conduct consistent with the nature of the advice relationship of trust and confidence) that we know today as the Registered Investment Adviser (RIA), preserving for consumers the choice of whether they wanted to engage a brokerage salesperson for the purchase of an investment product, or an investment adviser to receive counsel and advice.

Holding Out And Title Regulation In The Investment Advisers Act Of 1940

The distinction between – and separation of – sales from advice was so foundational to the emergence of investment counsel as a distinct profession from brokerage sales, that when the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 was implemented, Congress took several steps to ensure that the activities were separated.

The first was declaring under Section 202(a)(11) of the Investment Advisers Act that investment adviser registration (and the attendant RIA standards of conduct) will be required for “Any person who, for compensation, engages in the business of advising others… as to the advisability of investing in, purchasing, or selling securities”, unless a specific exemption applies.

In turn, to acknowledge that there were other industry participants who may be involved in aspects of a client’s financial matters, Section 202(a)(11)(B) created an exemption that “any lawyer, accountant, engineer, or teacher whose performance of such [advice] services is solely incidental to the practice of his profession” will not need to register as an investment adviser.

Similarly, Section 202(a)(11)(C) of the Investment Advisers Act declared that “any broker or dealer whose performance of such services is solely incidental to the conduct of his business as a broker or dealer and who receives no special compensation therefor” would also be exempted from investment adviser registration. In this context, though, Congress recognized that when it comes to broker-dealers in particular, one of the key determinants was not just whether the broker may have given the advice or not, but whether the compensation the broker received was “special compensation” for advice (as distinct from the commission compensation the broker might receive simply for effecting the sale of a stock or bond). In other words, in order to avoid investment adviser registration and its fiduciary obligations, the broker would need to give only “solely incidental” advice, and their subsequent compensation must only be for their brokerage transactions and not [special] compensation for that otherwise-incidental advice.

Furthermore, to prevent brokerage firms from marketing themselves as offering investment counsel, only to later claim that they weren’t acting as such (to avoid the fiduciary accountability that would otherwise apply), Congress enacted Section 208 of the Investment Advisers Act as well, which explicitly states that “it shall be unlawful for any person registered [as an investment adviser] to represent that he is an investment counsel or to use the name ‘investment counsel’ as descriptive of his business unless: 1) his or its principal business consists of acting as investment advisers; and 2) a substantial part of his or its business consists of rendering investment supervisory services” (where “investment supervisory services” is subsequently defined as “the giving of continuous advice as to the investment of funds on the basis of the individual needs of each client”). Furthermore, Congress also stated in Section 208(d) that it was not permissible to try to indirectly work around such limitations on how investment counsel services are represented to the public if they would not be permitted directly in the first place.

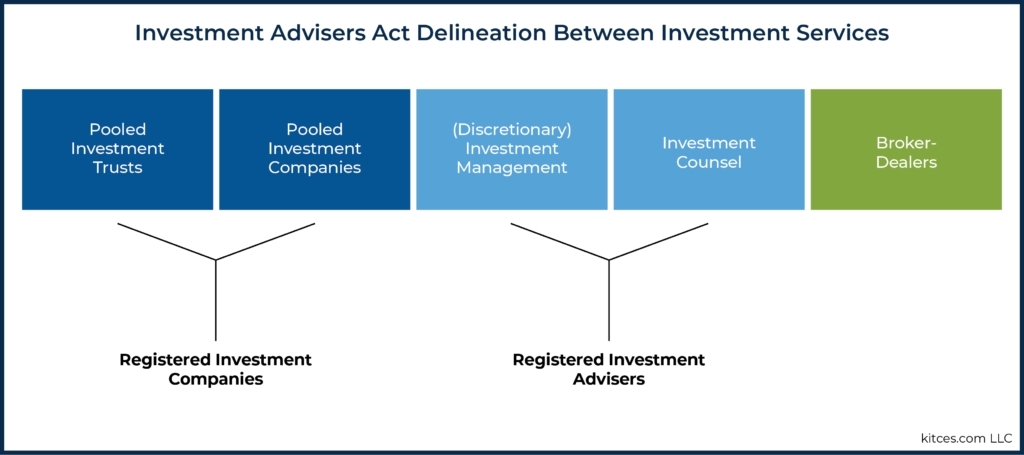

The end result of the Congressional framework in the Investment Advisers Act was that:

1) If someone held out as being in the business of financial advice for compensation, they had to become registered as an investment adviser and be subjected to its associated (fiduciary) standard of care

2) A brokerage firm could only avoid investment adviser registration if its advice was “solely incidental” and it did not receive compensation for any advice it did provide

3) If a firm was dually registered as a broker-dealer and an investment adviser, it still couldn’t market that it provides “investment counsel” advice services unless its principal business was acting as an investment adviser (which is important because if advice was its principal business, it would be impossible for such firms to later claim that their advice was “solely incidental” at the time of implementation)

As again, a key purpose of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 in the first place was to create a clear separation between the “tipsters and touts” of brokerage firms and “bona fide investment counsel” of the investment adviser. Which at its very core was centered on how firms marketed and held their services out to the public in the first place, with a regulatory framework that forced them to declare whether their primary or principal business was providing brokerage services (with only incidental advice), or providing investment counsel (as fiduciary advisors with no conflicted brokerage services).

The Evolution Of Industry And Language: From Investment Counsel(or) To Financial Advis(or)

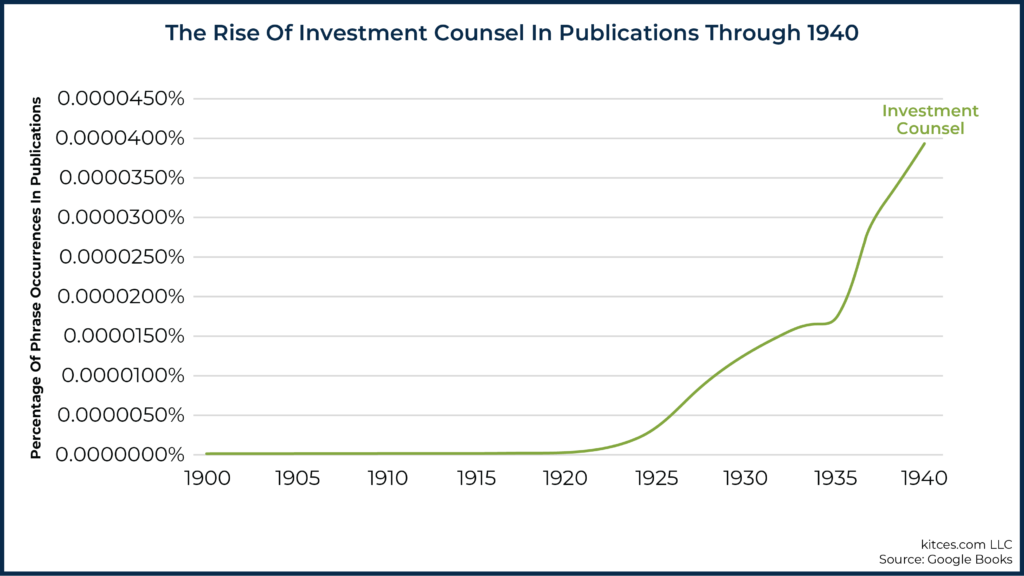

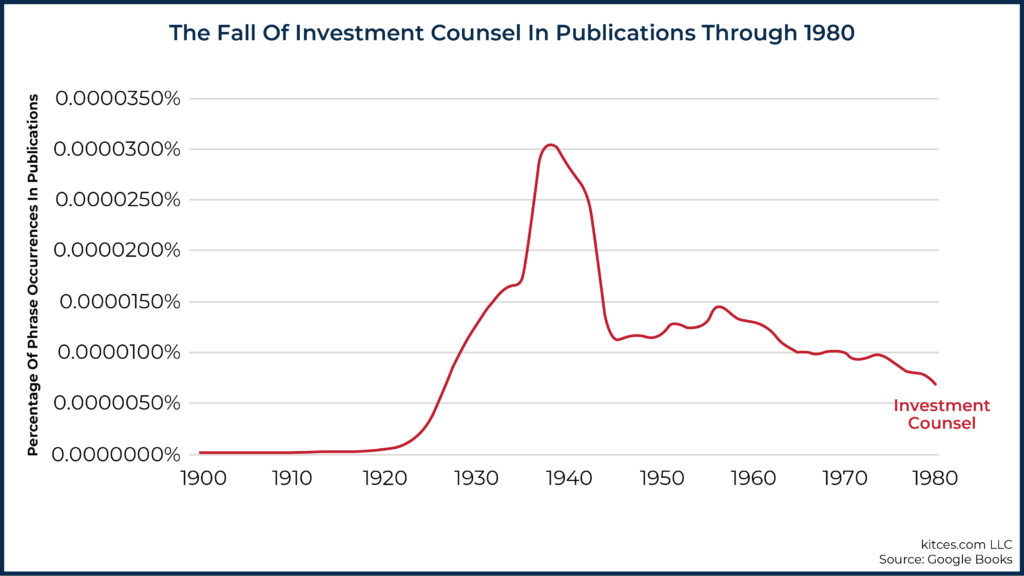

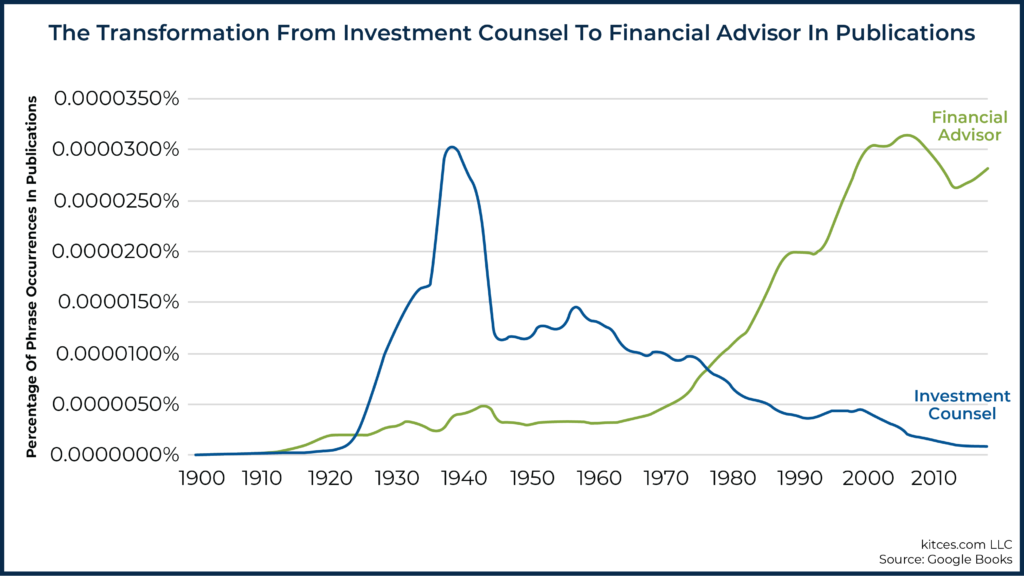

The Investment Advisers Act of 1940 was successful at reining in the then-problematic and blurred lines between broker-dealers and investment counsel firms. After the “investment counsel” title experienced a significant run-up in the 1930s – as it was the rising popularity of the term, used by more than “just” those in the bona fide investment counsel business, that necessitated the Advisers Act legislation in the first place – the use of the label fell precipitously, and ground even lower still in the decades that followed, as “investment counsel” was narrowed into the distinct and specialized professional service that the Investment Advisers Act was intended to create (and those providing brokerage services were forced to retreat from the now-regulated term under Section 208(c)).

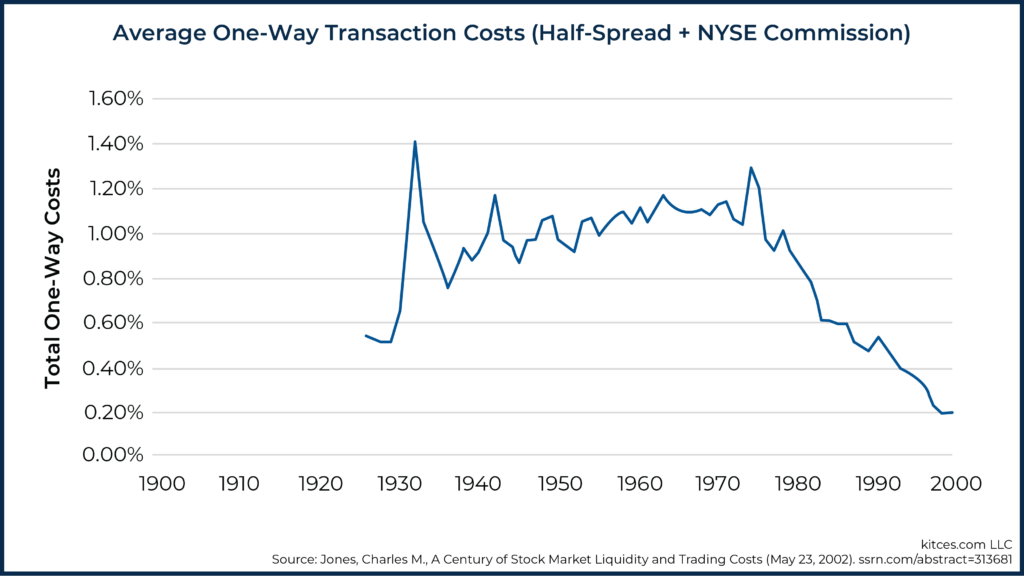

However, after several decades of stability and clearer delineation between brokerage and investment counsel services, the industry began to shift. In particular, in 1975, the Securities and Exchange Commission de-regulated fixed trading commissions in what was known as “May Day” and allowed brokerage firms to set their own rates on trades and compete with each other on price. In the decade that followed, there was a veritable explosion of “discount” brokerage firms, including today’s industry stalwarts like Schwab and Ameritrade, that aimed to use emerging new technologies (personal and mainframe computers!) to disintermediate human stockbrokers. And the technology won, as research by Charles Jones has shown stock trading commissions fell by nearly 90% in the 20 years following May Day.

The consequence of this shift is that brokerage firms had to reinvent themselves and their business model… which they did by shifting from stock and bond trading to the mutual fund business, facilitated by Rule 12b-1 created under Investment Company Act Release No 11414 which for the first time made it possible for brokerage firms to receive ongoing fees (reformulating the upfront trading commission into a levelized distribution and marketing fee of up to 0.75%, plus a shareholder servicing fee of 0.25%) to provide ongoing services to brokerage customers that did not involve the ongoing purchase and sale of securities (as mutual funds, once sold, are typically held for an extended period of time and not traded nearly as frequently as stocks and bonds).

Of course, getting paid ongoing distribution and marketing and shareholder servicing fees for increasingly technology-driven brokerage processes meant the stockbroker also had to reinvent their value proposition as well (or else customers would eventually question why they were still paying their broker an ongoing fee for a mutual fund sale that had occurred long ago)… leading brokers to go into the business of providing more upfront and ongoing financial advice to earn the ongoing 12b-1 fee… and the use of the term “financial advisor” suddenly exploded.

Notably, the industry had to adopt a new term and business card title besides “investment counsel”, because that title was regulated under Section 208 of the Investment Advisers Act. And in practice, "financial advisor" (and its alternatively spelled predecessor “financial adviser”) had already been ‘generic’ terms used in the industry for some time, and conveyed the desired value proposition to consumers in a self-descriptive manner. Despite the fact that such brokers still relied on the solely incidental exemption to avoid actually registering as being in the business of financial advice (business card title notwithstanding!).

The end result was that “financial advisor” quickly became the outright dominant term to describe the registered representative of a broker-dealer, as “investment counsel” fell by the wayside altogether. To the point that even the organization that championed the original legislation to protect the business of “investment counsel” – the Investment Counsel Association of America (ICAA) – in 2005 renamed itself to the Investment Adviser Association (IAA) to recognize the shift in industry language and terms away from Investment Counsel.

The Rise Of Financial Planning As A(nother) Distinct Emergent Profession

While shifting industry dynamics, value propositions, and the evolution of common use language itself have all helped to drive a transition from “investment counsel” to “financial advisor” as the dominant term over the past 80 years, it’s not the only significant shift in titles, marketed services, and value propositions in the advice business. Mirroring this rise over the past 50 years, in particular, has been the rise of the Financial Planner as well.

According to The History of Financial Planning by Denby Brandon and Oliver Welch, Loren Dunton first established the initial organization to institute (higher) standards for those who wanted to offer financial planning in 1969, and it was originally called the Society For Financial Counseling Ethics (later shorted to simply the “Society for Financial Counseling”), leveraging the then-popular “counseling” label beyond just investment counsel to describe the new broader financial counsel (advice) service.

The Society for Financial Counseling was in turn paired with a new membership association, called the International Association of Financial Counselors (IAFC), and an educational institution called the International College for Financial Counseling (which minted the first Certified Financial Planner certificants a few years later in 1973). It wasn’t until later in the 1970s that the International Association of Financial Counselors membership association became the International Association of Financial Planners (IAFP) instead (subsequently merged into the Financial Planning Association in 2000), and the educational institution was renamed from the International College for Financial Counseling into the College for Financial Planning (which still operates today) instead.

However, while financial planning made an early language shift from the “counsel”-dominant wording of the 1960s and prior to the “planning”-centric label of today, the emergence of financial planning since a fateful meeting at a Chicago airport hotel in 1969, and the rise of the associated CFP marks from the CFP Board, represents more than just a shift in the use of advisor titles and language (from counsel to advice). It also represents the emergence of a new scope of services – providing a “comprehensive” financial plan, following the CFP Board’s 7-step process, that goes beyond “just” the investment portfolio to the client’s more holistic and integrated financial picture.

Accordingly, in the decades that followed its origin, standalone financial planning software emerged as a tool that financial advisors could purchase to create and deliver financial plans to clients, major financial services firms began to sell “financial plans”, by the year 2000 the newly formed Financial Planning Association had 28,000 members, and there were more than 36,000 CFP certificants (which meant approximately 1 in 10 of all financial advisors had CFP certification).

In fact, the growth of financial planning as a distinct new discipline that complemented – and went beyond – traditional “investment counsel” grew so swiftly that by 1987 the SEC had worked with NASAA to issue IA Release 1092, which formally acknowledged the rise of financial planning, the breadth of financial planning services that were “principally advisory in nature”, and that receiving compensation for implementing financial plan recommendations – whether in the form of an advisory fee, some other fee, or commissions – would still be deemed compensation for advice that would trigger investment adviser registration.

Furthermore, IA Release 1092 went on to explicitly state that if a financial planner tried to give “generic non-specific investment advice” in their financial plan, and then subsequently implemented those recommendations in their capacity as a registered representative of a broker-dealer (or an agent of an insurance company), that person would “not be able to assert that he was not ‘in the business’ of giving investment advice” (i.e., a double-negative that meant delivering a financial plan and subsequently implementing that plan as a broker would still necessitate investment adviser registration, as the SEC noted that Section 208(d) of the Advisers Act “makes it illegal for someone to do indirectly under the Advisers Act what cannot be done directly” in the first place).

In 2005, the SEC issued its rule that “Certain Broker-Dealers Deemed Not To Be Investment Advisers” permitting brokerage firms to charge for fee-based brokerage accounts without registering as investment advisers, and in that rule outright recognized that “financial planners today belong to a distinct profession, and financial planning is a separate discipline from, for example, portfolio management… [and that] this development has occurred only relatively recently, over approximately the last 25 years – well after the enactment of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940”, stating that “the advisory services provided by financial planning… may extend beyond what Congress, in 1940, reasonably could have understood broker-dealers to have provided as an advisory service ancillary to their brokerage business”, and concluding that any broker-dealer cannot be engaged in “solely incidental” advice if it either: 1) holds out to the public as a financial planner or as providing financial planning services; 2) delivers to its customer a financial plan; or 3) represents to the customer that the advice is provided as part of a financial plan or financial planning services.

In other words, with its 2005 rule, the SEC effectively updated Section 208(c), which originally applied an RIA fiduciary duty to anyone who holds out as being investment counsel or providing investment counsel services, to recognize that holding out as a financial planner or providing financial planning services should and would similarly trigger investment adviser registration (and attach the RIA fiduciary obligation to that comprehensive financial planning advice).

The Repeal Of The 2005 Rule And The (Indefinitely Proposed) 2007 Rule

On March 30th of 2007, the DC Circuit Court of Appeals vacated the 2005 Broker-Dealer Exemption rule in the case of FPA vs SEC, on the grounds that the SEC exceeded its own authority in granting a new exemption under the Investment Advisers Act to allow broker-dealers to receive fee-based compensation in brokerage accounts without registering as (fiduciary) investment advisers… because, again, the ’40 Act stipulates that broker-dealers can only be exempt from RIA registration if their advice is solely incidental and they receive “no special compensation” (and the Court recognized that a broker’s compensation for a fee-based brokerage account would amount to such ‘special compensation’).

Unfortunately, though, when the 2005 rule was vacated – nearly two years after its enactment – it left an instant void in the then-current regulatory landscape, as large brokerage firms had already been in the midst of implementing the 2005 rule as originally written, and were suddenly uncertain what to do with their existing fee-based brokerage accounts when the court vacated the rule.

In response, the SEC quickly released a Proposed Rule (IA-2652) in mid-2007 to provide interim interpretive guidance, clarifying in what situations broker-dealers that had implemented fee-based brokerage accounts either would or would not now need to register as investment advisers because their fee-based brokerage services were no longer solely incidental (and finding, consistent with the FPA vs SEC ruling, that most such accounts would have to be advisory accounts, triggering an explosion in dually registered brokers in 2007-2008, and continued in the years since).

In its 2007 Proposed Rule, though, the SEC stated that it was not re-proposing the vacated Financial Planning section of the 2005 rule (which deemed that holding out as a financial planner or providing financial planning services, delivering a financial plan to the customer, or representing to the customer that the advice was part of a financial plan, would all trigger RIA registration and a fiduciary obligation), and instead intended to re-consider those issues in light of the then-pending RAND Study, which had been commissioned to evaluate the current landscape of consumer confusion between broker-dealers and investment advisers and the different standards of conduct that applied to each, and was expected to be delivered later that year (by the end of 2007).

In turn, the RAND Study delivered at the end of 2007 did in fact highlight substantial ongoing investor confusion about the difference between broker-dealers and investment advisers, driven by the ubiquitous use of the term “financial advisor” across both types of firms (which was the most commonly reported title, regardless of the type of services actually provided), and noting that “91% of [investors surveyed] reported that they thought that, if stockbrokers and financial planners offer the same type of investment advisory services, the same investor-protection rules should apply to both”, despite finding in practice that 79% of those holding out as registered representatives were offering financial planning services (while not registered as investment advisers, and claiming such financial planning advice was still solely incidental to be eligible for the lower standard applicable to broker-dealers).

Regulation Best Interest Reinterprets "Solely Incidental" And Holding Out Titles Yet Again

In the summer of 2019, the SEC issued its long-awaited “Regulation Best Interest” to update (and lift) the standards of conduct that apply to broker-dealers when they make investment recommendations to clients, in acknowledgment of the ongoing confusion with the investing public about the differences in services and associated standards of conduct for broker-dealers and investment advisers.

At its core, Regulation Best Interest (Reg BI) explicitly chose not to unify the standards for investment advisers and broker-dealers as it was authorized to do under Dodd-Frank Section 913(g), instead keeping separate the services (and conduct standards) of broker-dealers and investment advisers, and creating the new standardized Form CRS for both broker-dealers and investment advisers to provide to their customers/clients to explain their services and standards.

In its final rule, the SEC noted that it was declining to implement a provision from the original Reg BI proposal that would have enacted a broad restriction on the use of the term “adviser” or “advisor” (so-called “Titling Restrictions”), citing its own historical precedent that “in adopting the fee-based brokerage rule in 2005, we declined to place any limitations on how a broker-dealer may hold itself out or the titles it may employ”. Instead, the SEC chose to limit the ability of standalone broker-dealers to refer to themselves as “advisors” as a violation of their Disclosure Obligation (as an incorrect description of the capacity in which they are serving), but preserved the use of such title by dual-registrants. Which was problematic, as a dual-registrant marketing as a “financial advisor” would ostensibly create an expectation from that consumer that everything they receive would be “advice”, yet in practice, the SEC declared that “a dual-registrant is an investment adviser solely with respect to accounts for which a dual-registrant provides advice and receives compensation…” In other words, the SEC declared that dual-registrants could market an entire financial advice relationship, but not have to be fiduciaries for all of the subsequent implementation of that financial advice (if it occurred with commission-based products in non-advisory accounts).

In turn, Reg BI also included a new “Commission Interpretation Regarding the Solely Incidental Prong of the Broker-Dealer Exclusion from the Definition of Investment Adviser”, presented not as a Rule unto itself but an interpretation associated with the new Reg BI Rule, which substantively redefined "Solely Incidental" to mean any advice that is delivered “in connection with and reasonably related” the firm’s brokerage services.

The end result of this reinterpretation of Solely Incidental, and the associated narrowing of the scope during which even a dual-registrant is acting as an investment adviser (only with respect to a particular account and not with respect to the entire relationship with the client, even if a comprehensive financial plan has already been provided), was a substantive reversal of the entire foundation of Solely Incidental from being an exemption from what would otherwise be a requirement for any broker-dealer to register as an investment adviser when providing advice, to an exemption that avoids a broker-dealer ever needing to register as an investment adviser as long as it continues to also provide brokerage services!

For instance, imagine two identical “financial advisors”, who provide their clients with a comprehensive financial plan, and then help them implement the subsequent portfolio recommendations that financial plan entails. The first advisor operates as a registered investment adviser, and constructs an independent portfolio that meets the fiduciary standard of care, for which she receives a 1% AUM fee through her RIA. The second advisor operates as a broker, and implements the financial plan recommendation by constructing a portfolio of mutual funds using his company’s proprietary C-share mutual funds, earning the same total compensation in the form of a 1% C-share trail for the same asset allocation pursuant to the same advice process but using his own company’s (higher cost and conflicted) proprietary shares (for which the compensation to the broker may be the same, but the broker-dealer as asset manufacturer and distributor earns a greater profit from the end client through their conflicted broker).

Under Reg BI, because the broker delivered the financial plan “in connection with” the sale of his company’s mutual funds through their brokerage platform, that broker becomes “eligible” for the lower non-fiduciary standard of care under Reg BI because he chose to implement the plan in a more conflicted manner (using his company’s proprietary products)! Which is the antithesis of the founding principle of the Investment Advisers Act – to separate sales from advice – and the Solely Incidental exemption in the first place!

In other words, the current structure of Reg BI allows two “financial advisors” to engage in the same marketing of financial planning services, provide the same financial plan, recommend the same asset allocation recommendations, but implement with different (and in one case, more conflicted and higher cost) products.

And rather than recognizing that the delivery of advice and a comprehensive financial plan should elevate the standard of care on the recommendation of a proprietary product (because of the advice relationship of trust and confidence that has been created), instead the fact that a proprietary product would be sold at the end of the advice process allows the broker to ‘opt into’ a lower non-RIA non-fiduciary standard of care, at the exact moment that a fiduciary standard of care is most intended and necessary to protect the investor from conflicted advice!

Filing A Formal SEC Petition For Rulemaking On Financial Planner Title Regulation

Despite the central role that the Solely Incidental exemption has taken in the modern regulation of financial advice, due to the ongoing convergence of the broker-dealer and investment adviser channels and the rise of dual-registrants, as technology continues to automate or provide self-directed tools directly to consumers for traditional brokerage services and activities, and stockbrokers and registered representatives transition into higher value (and more advice-centric) services, the SEC has declined to engage in a formal rulemaking process on the Solely Incidental exemption that engages consumers and the full range of industry stakeholders.

Instead, the 2007 Proposed Rule for re-defining the Solely Incidental exemption remains in “Proposed” form, with the SEC having failed to take action to gather the necessary industry and consumer input to complete the rulemaking process and finalize the rule for 14 years, despite having originally committed to revisiting the issue within months with the then-pending RAND Report (which did, in fact, affirm the need for more substantive rulemaking). Furthermore, while Reg BI further modified the Solely Incidental exemption, it did so in the form of “interpretive guidance” that was also not subject to the full rulemaking process, despite its significant scope and impact in re-drawing the lines between broker-dealers and investment advisers. Combined together, the SEC has engaged in an ongoing 14-year series of modifications to the Solely Incidental exemption in a manner that is arguably outside its scope and authority as granted by Congress and permitted under the Administrative Procedures Act.

Perhaps even more concerning, though, is that the SEC’s non-Final-rulemaking actions over this 14-year period belie both the plain-text and dictionary definition of the “Solely Incidental” rule as written (as the word “incidental” does not mean “anything in connection with or reasonably related to”!), and ignore the SEC’s own long-established precedents with respect to the role of financial planning in particular in both IA Release 1092 and its 2005 Broker-Dealer Exemption. For which the SEC has not only reversed its position – having previously stated that holding out as a financial planner or providing financial planning services would not be solely incidental, and that implementing brokerage or insurance products pursuant to a financial plan would not be solely incidental, and now not only permitting both but in Reg BI outright denying it had previously placed limitations on financial planning titles and services – which again may be operating outside its authority and permitted rulemaking scope by reversing its own established precedents without providing any analysis of the industry or economic impact nor any justification for the change in policy.

In addition, the SEC’s ongoing reinterpretations of Solely Incidental also appear to be in conflict with the still extant Section 208(c), which not only restricts the use of the name “investment counsel” (which is arguably a moot point as the term is no longer in common use), but also restrict someone from “represent[ing] that he is an investment counsel” (i.e., claim that investment counsel services are being provided) unless their principal business consists of acting as an investment adviser, and those investment counsel services are a “substantial” part of their business. In other words, under Section 208(c), it would not be permitted to simply have an RIA registration in addition to being dually registered as a broker-dealer, as a substantial part of the dual-registrant’s business would have to actually be providing such advice services (an issue that Reg BI failed to reckon with altogether). And while “investment counsel” as a title is no longer still in general use, the service of investment counsel as described in the SEC’s own original 1939 study on Investment Counsel as providing individualized/personalized advice to individual clients about their investments is still widely implemented today. It is simply called “financial advice” or “financial consulting” or “wealth management”. But it is also not incorporated into the SEC’s Reg BI, nor any of its other current rules and regulations.

Furthermore, the continued growth of financial planning as a service unto itself arguably creates even more urgency for a rule. In 2005 when the SEC first issued its Broker-Dealer Exemption rule recognizing financial planning as a distinct profession whose scope of services unequivocally go beyond being “solely incidental” to brokerage services, there were approximately 49,000 CFP certificants, and Cerulli Associates estimated a total of 339,000 financial advisors (which meant nearly 1-in-7 financial advisors was holding out as a CFP professional providing such services). Today, the total number of CFP certificants is up to more than 90,000, and Cerulli estimates the total number of financial advisors has fallen to just barely over 300,000, which means almost 1-in-3 financial advisors holds out as a CFP professional. And despite a stagnant or slightly declining total headcount of financial advisors, the CFP Board continues to add nearly 5,000 new CFP certificants per year, continuing to compound the problem of financial advisors – including a wide swath of brokers and dual-registrants – holding out as comprehensive financial planners and providing such services, while continuing to rely on the Solely Incidental exemption to avoid fiduciary accountability for the financial planning advice they are providing.

As a result, XY Planning Network is hereby formally submitting a series of two Petitions to the SEC to take up the issues of both the Solely Incidental exception for broker-dealers providing financial planning services, and the broader use of "financial advisor", "financial planner", and similar titles by broker-dealers that imply their customers will receive advice services without actually being regulated as advisors (either at all, or not with respect to the full scope of the advisor-client relationship in the case of dual-registrants).

Accordingly, XYPN’s two Petitions to the SEC invite the Commission to re-evaluate financial planning titles, the holding out of financial planning services, the (advice) standards that would and should attach to those, and clarify how the Solely Incidental exemption and Section 208(c) should apply to brokers (including and especially dual-registrants) providing financial planning and financial advice services, by:

1) Formally completing the Rulemaking process of the 2007 Proposed Rule, to address both the concern that financial planning services themselves are so comprehensive that they cannot be solely incidental, and that the marketing of financial planning – whether by title or by function – creates an expectation that the consumer will receive advice services, requiring both investment adviser registration and the fiduciary duty that would apply, to the entire client relationship

2) Issuing rules to provide a modernized interpretation of Section 208(c), as while the statute itself stipulates “investment counsel” as a regulated title – which can only be changed by regulators – it also explicitly includes representing oneself as providing “investment counsel” services, which remains entirely relevant today, as investment counsel has become “financial advice” but is not being regulated as such under 208(c)

3) Clarify how a firm, and particularly its individual financial advisors, can rely on opposing exemptions for two opposing capacities with the same client by having “two primary businesses”, where the broker-dealer relies on the Solely Incidental exemption to implement as a broker and not an advisor, but the dual-registrant holds out as providing financial advice (“investment counsel”) under Section 208(c) as being in the principal business of financial advice. As by the definition of the word, there can be only one “primary” service, and an advice service must either be primarily in the business of advice (in which case all of advisor’s advice is regulated thereof), or it’s primarily in the brokerage business (and then it cannot hold out as providing advice/counsel services under Section 208(c)), but cannot be both a principal advice business and an incidental advice service at the same time.

Notably, our two Petitions for Rulemaking are not intended or expected to revisit the rulemaking process for Regulation Best Interest itself as it pertains to broker-dealers engaging in brokerage services. As the delivery of brokerage services themselves are outside the scope of financial advice, and we believe that Reg BI reasonably addresses the conduct of brokers acting in such a brokerage capacity, as long as such brokers are not providing financial advice or financial planning services, nor marketing and holding out to the public as providing such advice services or using advice titles that would imply and create an expectation of receiving such advice services, and are simply operating as brokers.

Instead, the intended scope of the rulemaking process for which we are petitioning would (re-)clarify the dividing line of when advice is delivered (subject to the standards of the Investment Advisers Act) and when brokerage services are delivered (subject to Regulation Best Interest), consistent with the original and still-current framework of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, where the SEC already has full authority to promulgate rules and modernize regulations and their enforcement.

Because again, the founding principle of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 was to assert a bright-line separation between sales and advice, as the emergent profession of investment counsel began to deliver a new level of advice to consumers, triggering an encroachment of brokerage firms into the advice business in order to sell more products, and a recognition by Congress that it’s crucial to separate the services of advice and brokerage sales (and then apply the appropriate standard to each).

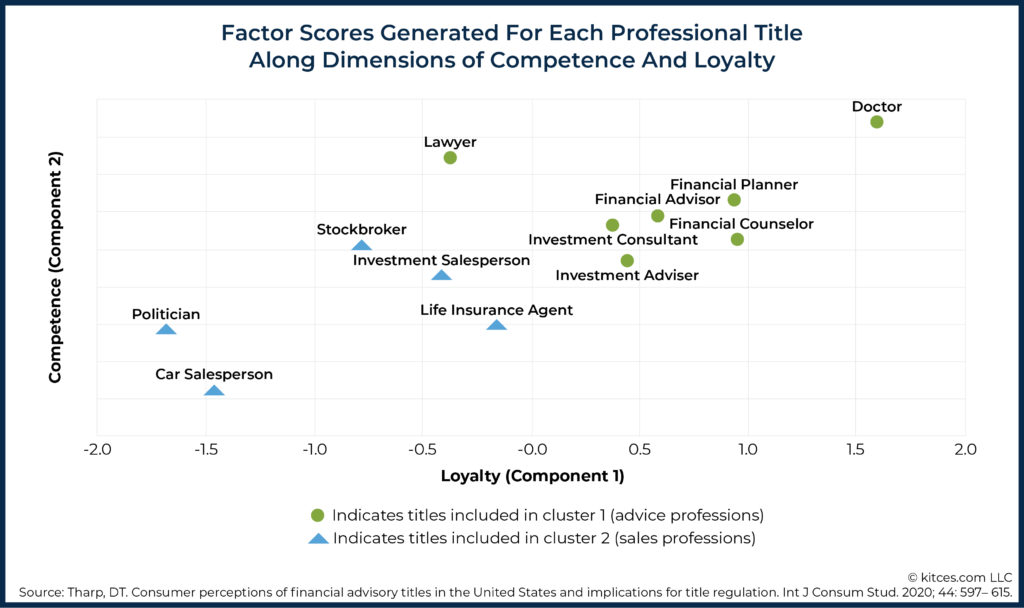

In the modern era, the lines have once again become blurred, as technology continues to drive a convergence of brokerage and investment adviser businesses, leading to consumer confusion that the RAND study evidenced in 2007, and a more recent Consumer Federation of America study revealed by analyzing 25 major brokerage firms and insurance companies and finding all of them were positioning what are legally salespeople not in the business of advice as being “financial advisors” and similar titles. And the stakes are high, as recent International Journal of Consumer Studies research by Dr. Derek Tharp on “Consumer Perceptions of Financial Advisory Titles” reveals that investors do in fact place significant weight on titles in making a determination of the service-providers expected competence (the Fiduciary Duty of Care) and Loyalty (the Fiduciary Duty of Loyalty), with “Financial Planner” and “Financial Advisor” forming an “advice cluster” of titles with substantively different expectations than Life Insurance Agent, Stockbroker, and as sales titles.

Or stated even more simply, as Congress recognized 81 years ago, words and titles matter, and help consumers to understand the scope of services that will be provided. In fact, “Truth In Advertising” and an obligation to avoid misleading advertising – including the use of titles and holding out – has been at the core of the Investment Advisers Act (and why Rule 208 on how an investment adviser represents themselves was included from the very start).

But as the financial services industry grows and evolves, from investment counsel to financial advice, and with the rise of the distinct but overlapping profession of financial planning, it’s time to update the rules for the modern era, eliminate the loophole that allows a broker and advisor to market the same financial planning services, deliver the same financial planning recommendation, receive the same amount of financial compensation for that planning advice, but be eligible to opt into a lower standard of care by choosing a more conflicted implementation model, and re-assert the bright dividing line between (brokerage) sales and (financial) advice.

Which can both preserve and create a clearer choice for consumers about which type of financial services relationship – sales versus advice – they would prefer to engage, once the titles and marketing they see make it clear which service they would be choosing.

Respectfully,

- Michael Kitces

Co-Founder, XY Planning Network

Where are the petitions so the public can read them for themselves?

They’ve been filed with the SEC, but it takes the SEC a few days for the SEC to post them publicly to their website. We’ll include links for them as soon as they’re publicly available!

– Michael

I’d probably even want to go as far as to limit the terms people can use into the ones that have legal definitions so we can eliminate “wealth management” being seen in relationship to “financial planning” as facial quality tissue is in relationship to toilet paper. And maybe even have people holding out as “financial advisors” to pick a lane into either “investment advisors” or “financial planners”.

Are any organizations publicly in support of this petition to the SEC? Or is it just XYPN founders and Focus Financial?

XYPN Founders (Michael Kitces et al.) —

https://www.xyplanningnetwork.com/team/

Focus Financial has no relationship to this at all. It’s been submitted by XY Planning Network.

You’ll see a number of additional organizations voicing support in the weeks to come. Since the petitions were literally filed the morning this article was published, and it takes the SEC several days to publish Petitions on its site, other organizations have literally not even HAD the opportunity to review and support yet. 😉

– Michael

What’s the old adage? The best thing about knocking your head against the wall, is that it feels so good when you stop.

The “butcher vs. nutritionist” analogy is a great one! At least the consumer has a basic understanding of what they’re about to be sold.

Many of the problems (conflicts of interest) in our industry could be solved with a few “simple” rule changes:

– Eliminate dual registrants. A firm may only be Broker-Dealer or an Investment Adviser: NOT BOTH.

– Individuals may only serve in one capacity. As a registered rep of a broker-dealer or as an investment adviser representative: NOT BOTH.

– The only titles permitted are “Registered Representative”, “Investment Adviser Representative”, or “Financial Planner” (in which case, you must be an “Investment Adviser Representative” AND hold a degree in financial planning or have a certification/designation such as CFP, ChFC, AWMA, PFS, etc.).

– Investment Adviser firms may not receive any form of third-party compensation (other than customary benefits provided through their custodial relationship, which are designed to assist in servicing clients): No revenue sharing of any type. The IA may only be compensated by the advisory fees paid to them by clients.

I’m not going to hold my breath waiting for ANY of the above to EVER happen…

Michael,

As a CFP, fee-only, “Financial Advisor” I completely support and thank you for your against-all-odds efforts to resolve this important issue. I think, though, that the only possible solution would be to do it by exclusion i.e. legally prohibit registered representatives and insurance agents from RIA/IAR registration. Trying to do it by inclusion is impossible given the professional field overlap and comprehensive nature Financial Advice/Planning/Counseling/Coaching entails. Would it be fair for CPAs, EAs, JDs, CFAs, RR, Mortgage brokers, Insurance Agents, etc. to object to anyone not having any of those designation or licenses from calling themselves (Comprehensive) Financial Planners?

Go get’em and best of luck

In Australia in 2016 the terms Financial Planner & Financial Adviser were enshrined in law.

The terms cannot be used without meeting the criteria to be qualified.

https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/f42b59d88b5077de9357227fd7460375de8e61caa736a053d0eddd4d5377db01.jpg

What is the distinction between promoting sales techniques nearly every day on the Nerd’s Eye blog and the “salespeople” called out in this article? Isn’t managed money essentially sales at this point anyway? What’s a label if it all means the same thing anyway?

AJ,

Yes it is true that advice is ‘sold’. Any service-provider still has to persuade a client to pay their for their services and expertise.

Nonetheless, the difference is that Advice is selling a service that’s paid by the client, while Brokerage is selling a product that’s paid by the manufacturer.

That’s not a distinction I’m just making up. It’s WHY brokers and advisors had different regulatory standards (suitability versus fiduciary) and different regulatory exams (Series 6/7 vs Series 65) in the first place.

– Michael

Guess we’ll have to agree to disagree on that point 🙂 Thoughts on the attached?

https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/d555d621c4a92d51dab11556406c4da6665e44b7c471a46804168affa953a266.png

Part of giving advice is recommending products. That’s still different than selling the products.

You CAN’T get most drugs unless they’re prescribed by a doctor. But the doctor isn’t employed by the drug manufacturer, and isn’t compensated by the drug manufacturer. Prescriptions for drugs are not acting as a salesperson for the drug company, even if the patient still ends out purchasing the drug. The same is true for advice and financial services products.

Thus why we wrote more than 5 years ago that a fiduciary rule would likely be the BEST thing that could happen for annuity sales in the long run (talking about the likely rise of fee-based annuities long before any companies besides Jefferson National were making them widely available to RIAs): https://www.kitces.com/blog/why-dol-fiduciary-wont-kill-annuities-it-will-make-them-stronger/

– Michael

Feels like you’re writing the wrong people in these petitions. But it would be good to actually see them…why not upload it here?

The SEC will be posting them directly (as they do with all Petitions – they’re public documents) at https://www.sec.gov/rules/petitions.htm

I’m told it often takes them a few days to process, though. So they’re just not quite up there yet (at least as of this message).

– Michael

It seems unethical to put out press releases and try to rack up PR points without releasing it to the public. I imagine it makes some wonder if this info is already released to some insiders. Just release it already…what are you waiting for?

AJ,

These were literally submitted to a PUBLIC Petition system in the first place. The entire process is public. The press coverage went out AFTER the petitions were submitted to the SEC so that they would be available via the SEC for anyone who wanted to view them.

The SEC typically posts Petitions within a day or two of when they are submitted. Another Petition that was submitted to the SEC the same time as XYPN’s has already been made public on the SEC’s website. The SEC seems to have been a bit slower in posting the XYPN petitions, but we don’t control the SEC’s internal processes, beyond following the processes they stipulate for submitting a public petition.

Nonetheless, the point remains that the entire process is public, and the petitions were submitted to a public system. The reality is that if the SEC acts on the Petitions, the rulemaking process will likely be underway for the next 18-36 months. It’s unfortunate the SEC has taken a few more business days than usual to post the Petitions that were submitted to them, but we’re not even 1% of the way into the process of rulemaking yet. 😉

– Michael

In the UK financial planning is a service unto itself, a distinct profession. We have a financial planning movement, which is neither advice nor sales. Planning creates the expectation that we are primarily in the planning business. Advising creates the expectation that you are primarily in the advising business. Selling creates the expectation that you are primarily in the selling business. We do not agree that planning creates the expectation that we are in the advice business, or that planning is principally advisory in nature. Generic non-specific investment advice can be a standalone service, we refer to it as generic advice and financial education. More often than not the holistic and integrated financial picture for the client has little to do with investment portfolios, and far more to do with creating assets through ways of working. We sell plans, not products. We are independent, hired by the client, and receive fee compensation by the plan. The fee is not contingent on implementation of the plan, nor is it related to the amount of wealth held in financial assets. Our fees are the same, whether wealth is property, financial, physical, private pension, state pension, or business. We call it non-intermediating financial planning.