For many financial advisors, helping affluent clients with charitable planning strategies is a common objective, particularly those who have more than enough to satisfy their own retirement and family goals and also wish to make substantial charitable contributions that will help others in need. Which in recent years has become even more flexible, as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act increased the percentage-of-AGI limit on cash contributions from 50% to 60%, and the CARES Act (as extended by the Coronavirus Stimulus Act) further increased the limit from 60% to 100%(!) of AGI, making it possible for the most charitable inclined clients to fully offset their income and reduce their tax bill to zero! Yet as it turns out, reducing one’s tax bill all the way to nothing actually produces tax savings at the lowest tax brackets… such that in the end, the new 100%-of-AGI charitable giving limit actually is not such a great deal after all!

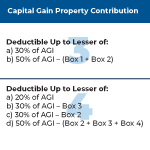

Taxpayers who itemize deductions on their Federal income tax return can generally deduct contributions made to qualifying charitable organizations up to some percentage of their Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), traditionally ranging from 20% to 50% of AGI, and is dictated by such factors as the nature of the asset donated (e.g., cash gifts vs Capital Gain property) and the type of charitable organization receiving the gift (e.g., “50% Limit Organizations”, which include churches, educational institutions, hospitals, government entities, and public charities; and “Other Charitable Organizations” which include any charity not considered a 50% Limit Organization).

As a result, charitable contributions can be categorized into four primary groups: 1) cash contributions to 50% Limit Organizations, 2) cash contributions to Other Charitable Organizations, 3) Capital Gain property contributions to 50% Limit Organizations, and 4) Capital Gain property contributions to Other Charitable Organizations. And when contributions in a given year overlap between multiple categories, there is a specific order of operations to be employed, which first prioritizes cash over Capital Gain property contributions, and then 50% Limit Organizations over Other Charitable Organizations.

With the CARES Act of 2020, though, a new 100%-of-AGI limit on deductions for category 1 – certain “qualified” cash contributions to charities – was implemented (and extended through 2021 with the passage of the Consolidated Appropriations Act) to provide some additional incentives for charitable giving in the face of the financial impact that COVID-19 has had on Americans. Which means that taxpayers can technically offset all of their taxable income with charitable contribution deductions, resulting in a tax bill of $0!

Still, though, the fact that one can take charitable contribution deductions up to 100% of their income doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a good deal to actually do so. Because it is often simply be better for a taxpayer who normally finds themselves in a higher ordinary income tax bracket to go ahead and actually pay taxes on a portion of their gross income at lower tax rates (and not offset it with a charitable deduction), thereby preserving their charitable giving (or at least their charitable deduction) for future years when their rates may be higher again. And by spreading charitable contributions out over multiple tax years (and leveraging the five-year carryforward allowances for unused charitable contribution deductions), they can effectively offset income in years when they would be subject to higher tax rates, thereby producing a greater total tax benefit.

Ultimately, the key point is that while the new CARES Act (now extended by the Coronavirus Stimulus legislation) makes it possible to claim Qualified Contribution deductions (with 100%-of-AGI limits) and zero out one’s tax bill, in practice it is rarely a good idea to do so. As while there is a small group of ultra-high-income individuals who can occasionally still benefit from using the increased deduction limits they provide, in most cases, high income donors are better served to stretch out or carry over a portion of their charitable giving (and charitable deductions) across multiple high income years instead. Though for financial advisors who have clients who won’t necessarily benefit from the provision, simply being able to explain why the better option would be not to take potential deductions as soon as possible can be a valuable service, in and of itself!

Welcome back to the 212th episode of the Financial Advisor Success Podcast!

Welcome back to the 212th episode of the Financial Advisor Success Podcast!