In 2014, the Affordable Care Act (also known as “Obamacare”) established state health insurance programs with the intent to make health insurance accessible to all individuals and families – including the self-employed – without needing to obtain coverage through a (larger) group employer. For those with lower income who may not be able to afford coverage from the state marketplaces, the Affordable Care Act also established the Premium Tax Credit (PTC; also known as the Premium Assistance Tax Credit, or PATC), a fully refundable Federal income tax credit meant to subsidize the cost of insurance premiums for individuals who purchase insurance through the Health Insurance Marketplaces. The PTC provides support by effectively capping health insurance premiums (for the second-lowest-cost Silver health plan available in their state) to a certain percentage of the individual’s household income, calculated on a sliding scale for those earning up to 400% of the Federal Poverty Level (which amounts to $104,800 for a family of 4). Though because of the unique control that self-employed individuals have over the income and expenses of their businesses, they have a unique opportunity to make business decisions that can also help maximize their ability to receive Premium Tax Credits.

In this guest post, Vinicius Hiratuka, founder of Elevated Retirement Financial Services, examines planning strategies that self-employed individuals can use to manage their reportable income levels in order to qualify for the Premium Tax Credit, and maximize the amount of the PTC they receive.

Maintaining income levels within the allowed threshold to qualify for the PTC in the first place - between 100% and 400% of the Federal Poverty Limit (FPL) - is crucial because as little as a single dollar of income over the 400% FPL will result in the complete loss of the PTC.

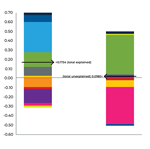

Maximizing the PTC (once meeting the FPL-qualifying threshold) is largely influenced by managing above-the-line tax deductions (that affect the calculation of an individual’s AGI used to determine the PTC in the first place). As such, self-employed individuals often have greater flexibility to employ tax-savings strategies through business expense and retirement contribution planning, such as accelerating business expenses (e.g., at the end of the year) to reduce income and contributing to Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) and/or tax-deferred retirement accounts, which can be used to increase above-the-line deductions, and thus reduce their income for purposes of calculating the PTC itself, thereby increasing the amount of the PTC benefit being received.

However, financial advisors should assess if and how their planning strategy will affect both their self-employed clients’ PTC benefit and also their Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction. For example, while a Solo 401(k) contribution may decrease income (which both improves the PTC and reduces the Federal tax liability), the reduced income may also make the QBI deduction lower. As a result, making contributions to a Traditional IRA account instead of a Solo 401(k) could be even more beneficial, as the result would still reduce MAGI to increase the PTC, but would not reduce the QBI deduction for the self-employed individual (as IRA contributions are considered personal and, technically, not business-related contributions).

Ultimately, financial advisors can help clients by simply clarifying what health insurance options and potential Premium Tax Credit assistance is available to them. This can help the client understand how the PTC benefits their tax situation, and at the same time alleviate the fears that many clients who are considering self-employment have about the high cost of health insurance for self-employed business owners. Advisors can also add value for their clients by walking them through detailed tax projections that illustrate how the PTC (and other deductions and credits) play into their overall tax liability. Not only does this provide potential opportunities to strengthen the relationship with clients’ tax professionals, but at the end of the day, the collaborative efforts will ensure that the client has a more holistically prepared financial plan, and health insurance they can afford to keep!

Welcome back to the 190th episode of Financial Advisor Success Podcast!

Welcome back to the 190th episode of Financial Advisor Success Podcast!