It’s a long-standing principle of the tax code that expenses incurred for the production of income or management of assets (e.g., an investment advisory fee) is a cost that can be applied against the income produced – in other words, deducted as a pre-tax expense. Unfortunately, though, under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, the entire category of “miscellaneous itemized deductions subject to the 2%-of-AGI floor” was repealed… which included the deduction for investment advisory fees, making them no longer able to be paid directly on a pre-tax basis.

However, the ability to pay for the cost of an advisor on a pre-tax basis is still preserved in situations where the fee can be paid directly from a tax-preferenced account or product. As a result, advisory fees deducted directly from an IRA are still pre-tax, and commissions subtracted directly from the net asset value of a mutual fund (or the cash value of an annuity) are still pre-tax as well. The caveat, of course, is that registered investment advisers charging fees cannot receive commissions from mutual funds or annuities in the first place, making it effectively impossible to charge clients on a pre-tax basis.

When it comes to annuities in particular, the fundamental challenge is that even though there’s a cash value from which advisory fees could be paid – roughly akin to deducting advisory fees directly from an IRA – annuities have historically been subject to a peculiar wrinkle in the tax code: any amount received from an annuity that isn’t received as an annuity (i.e., as annuitized income payable at regular intervals for life or a period certain) will be treated as a withdrawal, and taxable to the extent that there are any gains in the annuity contract. Which includes not only traditional distributions from an annuity to the owner, but any amount paid by an annuity on behalf of its owner… effectively rendering advisory fees from an annuity to not only fail to be a pre-tax payment, but even worse to actually trigger tax consequences as a taxable distribution. Even though, again, the same advisor could receive a 1%/year commission trail from the annuity for the same net compensation without triggering a taxable event.

The key distinction is that while the IRS deems a 1% per year advisory fee that’s paid from the cash value of an annuity to be a taxable distribution to the annuity owner (who then ostensibly pays his or her advisor), any trailing commission paid to the broker who sold the annuity is instead deemed to be an expense paid by the annuity company (and deducted from the value of the annuity), and therefore is not technically a taxable distribution.

This standard treatment could be undergoing a significant shift, however, after a coalition of insurers banded together to submit a series of Private Letter Ruling (PLR) requests, asking the IRS to change its position and consider advisory fees on so-called “fee-based” annuities to be treated like any other retirement account or internal mutual fund expense ratio (i.e., as expenses paid by the account itself, rather than as a distribution to or on behalf of the owner). And, given that these contracts are specifically designed to be fee-based (and therefore RIA-supported), the IRS acquiesced and ruled that, since the payment on ongoing fees for advice are “integral to the operation of the contract,” those fees should be considered to be an expense of the annuity itself, which are authorized by the owner, withdrawn by the annuity company, and paid directly to the (registered investment) adviser.

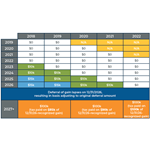

It’s important to note that these are “only” private letter rulings, not an actual change in the tax code, and include several key stipulations that, if not followed, could make it difficult for other annuity carriers to receive similar treatment. Specifically, the PLRs stipulate that in order to receive the favorable tax treatment, annuity advisory fees can’t exceed 1.5% per year, must be paid by the annuity carrier to the RIA, should only pertain to the advice on that particular annuity, and must be explicitly authorized by the owner.

Still, while the new ruling is a major breakthrough for the annuity industry’s attempts to create more RIA-friendly annuity solutions, it remains to be seen whether fee-based annuities will gain wider adoption with advisory firms. As the reality is that there are still numerous operational and technical issues that must be addressed, including facilitating graduated advisory fee schedules (that also don’t exceed the 1.5% per year cap), integrating annuity sub-accounts into existing RIA portfolio model management tools, the ability to open new accounts at scale (for existing RIAs with a sizable base of existing clients), and being able to coordinate various distributions (leveraging an annuity’s available living benefit guarantees) amid a much more complex asset mix that includes non-annuities the advisor manages as well.

The key point, however, is that the recent PLRs from the IRS are at least a step in the right direction, bring important parity and tax law consistency between advisory fees for tax-qualified retirement accounts and advisory fees for non-qualified annuities, and provide another potential tool that advisors can use to better serve their clients… particularly in unique situations where a client specifically needs an annuity, or wants to replace an existing annuity. From a systems and practical perspective, though, there are numerous challenges that still must be addressed, particularly for larger advisory firms operating at scale, before fee-based annuities gain wider acceptance among RIAs.

Welcome back to the 139th episode of Financial Advisor Success Podcast!

Welcome back to the 139th episode of Financial Advisor Success Podcast!

Welcome back to the 138th episode of Financial Advisor Success Podcast!

Welcome back to the 138th episode of Financial Advisor Success Podcast!