With the number of different financial advisor business models and firm types that are in existence, prospective financial advisors have a lot of options when it comes to finding "real" financial planning jobs - the kind that don't have sales requirements, and are really focused on (learning to give) financial advice. And the reality is that not all financial advisory firms are equally great to work for. But the good news is that the best financial advisor companies to work for do share a number of common traits, that can make them easier to identify.

In this week’s #OfficeHours with @MichaelKitces, my Tuesday 1PM EST broadcast via Periscope, we talk how to find the best financial advisor companies to work for, and why those companies tend to be larger companies with recurring revenue and a healthy growth rate.

Perhaps not surprisingly, if you want to find the best financial advisor companies to work for that won't just make you a salesperson working on commission, the first secret is... to find companies that don't work primarily on commission. It sounds intuitively obvious – if you don’t want to work on commission, don’t go to a company that pays its advisors on commission – but the real reason this matters is more nuanced. Because the fundamental challenge for any financial advisor who is paid on commission is that, no matter how successful you were last year, when you wake up on January 1st, your income is zero (or close to zero with some small commission trails). Which is crucially important, because it means commission-based advisors can’t afford to reinvest into staff and create entry-level very many financial planning jobs. As a result, these firms tend to only hire salespeople who can go get more clients (and perhaps some administrative staff), but not real financial planning positions focused on financial advice itself.

The next criteria for finding the best companies to work for is that a company should be growing. At a minimum, you want a firm that is growing at 10% a year. Ideally, one that is growing at 15% to 25% a year. And the reason why is because the simple math of growth means a firm growing at 15% per year will double its size in about 5 years with compounding. Which means twice as much revenue, twice as many clients, and since advisors can only serve so many clients at a time, twice as many clients means twice as many financial advisor jobs in the coming years. And with the creation of many new jobs will also come new opportunities to grow in your own career path as a financial advisor.

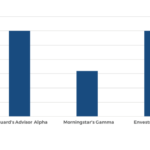

Which leads us to the third and final factor that helps to determine which are the top financial planning firms to work for. Simply put: the best companies to work for are the biggest ones (ideally, a firm with at least $3 billion of assets under management or about $25 million of revenue, all the way up to mega-national firms like Vanguard's Personal Advisor Services and Schwab's Intelligent Advisory and Portfolio Consulting groups). This is actually a very controversial view, but the industry benchmarking data shows that the biggest firms are the ones adding the most new revenue, the most new clients, and consequently are the most likely to be hiring financial planners (and with recurring revenue, those jobs are likely to be focused on really providing financial planning advice).

The bottom line, though, is just simple to recognize to recognize that the best financial advisor companies to work for have three key traits: a recurring revenue business model, a healthy growth rate, and some size and scale to have a deep bench of new opportunities. The caveat to this is that because these firms tend to pay the best and have the best career prospects, they are also the most competitive. Which means if you want a job at one of the best firms to work for as a financial advisor, you better bring your A-game!

Welcome back to the fortieth episode of the Financial Advisor Success podcast!

Welcome back to the fortieth episode of the Financial Advisor Success podcast!