Even as the total number of financial advisors is in decline since 2000, the number of CFP certificants has been on the rise, driven by both the rising demand from consumers for financial planning advice, and a need and desire for financial advisors to differentiate themselves by providing financial planning services.

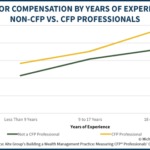

And according to a recent study by Aite Group, it turns out that getting the CFP marks really are good for business, with the average solo CFP certificant generating 40% more revenue, the average experienced solo CFP certificant generating 80% more revenue, and financial advisor teams generating 44% more revenue when they include at least 1 CFP professional. In turn, this results in the average CFP professional generating 14% to 33% more income than non-CFP advisors, even after controlling for years of experience.

Notably, though, the study also finds that while CFP certification is associated with higher income, it’s not necessarily because advisors get new clients simply by showing off their CFP marks. Instead, the positive impact derives primarily from enhanced credibility, improved technical expertise and knowledge (which also leads to better self-confidence as an advisor), and greater client satisfaction with the advisor’s (more comprehensive financial planning) services.

And given that some of the fastest-growing channels for CFP certification are now employee advisor roles at either independent RIAs or “online” brokerage/investment firms with retail advisors (i.e., Schwab, Fidelity, and TD Ameritrade, and now Vanguard), it appears that obtaining the CFP marks are increasingly becoming a key step to climbing the employee ladder as a financial advisor as well.

To say the least, though, with the potential for a 14% to 33% increase in lifetime earnings, at this point the CFP marks continue to more-than-sufficiently-justify the $3,000 - $10,000 required investment into a CFP educational program to obtain the certification!