Executive Summary

Among the several different types of retirement plans that are available to self-employed workers, solo 401(k) plans can offer the most flexibility and the ability to contribute the highest amount of tax-advantaged savings. But alongside those advantages, there are some specific rules and regulations that are unique to solo 401(k) plans, which can add to the complexity of setting up and maintaining a plan. And for advisors who serve self-employed clients, managing a solo 401(k) plan is often a different process than managing other types of investments.

However, the advantages of solo 401(k) plans – which include higher contribution limits for individuals with moderate incomes as well as the ability to make Roth contributions to the plan (plus additional nondeductible contributions which can be converted into even more Roth dollars) – mean they can often be worth the added complexity, particularly for individuals who want to save a high percentage of their income and/or build tax-free Roth savings. They can also permit participants to take loans from the plan, creating a source of emergency funds without the need to make a (potentially taxable) distribution.

Setting up and maintaining a solo 401(k) plan involves creating plan paperwork (including a written plan document and adoption agreement), keeping records of contributions and withdrawals, and for plans with more than $250,000 in assets, filing Form 5500-EZ annually with the IRS. Business owners typically outsource some or all of these tasks, and they can do so in one of two ways: by choosing a pre-approved, ‘off-the-shelf’ plan with a broker-dealer firm (who then serves as custodian for plan assets), or by hiring a third-party plan provider to create a ‘self-directed’ plan, which can invest in a wider range of assets.

Although both types of solo 401(k) plans come with particular benefits, there are also tradeoffs to each approach. Off-the-shelf plans can be easier to administer, since the broker-dealer handles most of the plan paperwork and holds the plan assets often for little to no cost. However, off-the-shelf plans also tend to offer fewer options; for example, TD Ameritrade’s merger with Charles Schwab resulted in the elimination of Roth features from their off-the-shelf solo 401(k) plan.

Self-directed plans, meanwhile, offer more ability to tailor a plan’s features to an individual’s needs. These features can include the ability to make Roth or nondeductible contributions, to take loans from plan assets, and to invest in non-traditional assets such as real estate, crypto assets, and precious metals – many of which are not allowed by most off-the-shelf solo 401(k) plans. But self-directed plans can be complex to manage, with the possibility of assets being held in multiple locations (as well as the responsibility of the plan participant to avoid investing in prohibited assets or making prohibited transactions), and costs that typically include startup fees of several hundred dollars, along with additional fees for ongoing maintenance.

The key point is that advisors can offer a valuable service by guiding their self-employed clients to the right solo 401(k) plan option, and by filling in the gaps between whatever services the plan provider performs and what the client is responsible for (such as opening accounts, keeping track of contributions and distributions, or preparing Form 5500-EZ). Ultimately, with the potential for added wealth that solo 401(k) plans can create, making the process of managing the plan a little easier for clients is a great opportunity to provide value that the client can see from year to year.

One of the many decisions that self-employed business owners are responsible for is choosing a retirement plan to contribute to. Several types of plans exist for self-employed workers to save for retirement in a tax-advantaged way, including SEP and SIMPLE plans. But among the various options, solo 401(k) plans – also known as individual 401(k), I-401(k), and solo(k) plans – offer some of the most versatile and powerful options for self-employed workers to build retirement savings.

The solo 401(k) plan, in its current form, came into being in 2001 when the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act made it possible for self-employed individuals to make separate contributions to a 401(k) plan both as an employee and as an employer. This change greatly increased the amount of tax-advantaged savings a self-employed worker could contribute to a solo 401(k) plan on an annual basis compared with the other types of plans available, such as SEP IRA and SIMPLE IRA plans.

Later enhancements, like the Pension Protection Act of 2006 (which allowed for direct Roth conversions from 401(k) plans) and IRS Notice 2014-54 (which allowed individuals to split pre-tax and after-tax funds when making Roth conversions from 401(k) plans), further increased the value and appeal of solo 401(k) plans. Unlike other types of self-employed retirement plans, solo 401(k) plan participants were now able to take advantage of advanced tax planning options like the Mega-Backdoor-Roth strategy (discussed below) to maximize their tax-advantaged savings each year.

However, because of some of the requirements for solo 401(k) plan owners (also known as ‘participants’) – such as increased paperwork and tax filing requirements, as well as a multi-step calculation to determine how much can be contributed to the plan – solo 401(k) plans have acquired a reputation of being somewhat onerous to maintain, meaning that they tend to be underutilized by self-employed workers despite their many potential advantages.

For financial advisors, then, helping self-employed clients navigate the process of managing a solo 401(k) plan offers a way to unlock its value and potentially create significant amounts of tax-advantaged wealth for retirement.

How Solo 401(k) Plans Work

Anyone who is self-employed and has no employees other than themselves (with the exception of the business owner’s spouse as the only other employee) can open and contribute to a solo 401(k) plan. Conceptually, solo 401(k) plans work the same as a 401(k) plan for a larger company: The ‘employer’ and ‘employee’ are both allowed to make contributions on the employee’s behalf. But because a self-employed person is both the employer and employee in a solo 401(k) plan, there is effectively one annual contribution with two different layers, one each for the ‘employee’ and ‘employer’ portion, as follows:

- For the employee’s portion, the individual can contribute up to 100% of their compensation up to an annual limit ($20,500 for 2022 and $22,500 for 2023); and

- As the employer, the individual can also contribute up to 25% of their compensation.

The combined limit of the two types of contribution, along with any other qualified employer retirement plans the individual participates in, is the lesser of 100% of compensation or $61,000 in 2022 ($66,000 in 2023), plus additional catch-up contributions of $6,500 in 2022 ($7,500 in 2023) for individuals over age 50. (For the rest of this article, 2022 contribution limits will be used for simplicity’s sake.)

The IRS defines compensation for the purposes of calculating a solo 401(k) plan’s contribution limit as “net earnings from self-employment”, which is a self-employed individual’s net Schedule C income (or alternatively, their W2 wages as owner-employee of an S corporation) minus one-half of their self-employment tax. Determining net compensation requires a three-step calculation:

- Calculate the earnings subject to self-employment tax (net Schedule C income or S corporation wages multiplied by 0.9235).

- Multiply the result of Step 1 by 1/2 of the self-employment tax rate (0.153 ÷ 2 = 0.0765). If the individual's earnings subject to self-employment tax are more than the Social Security wage base ($147,000 in 2022), multiply the first $147,000 by 0.0765 and the remainder by 0.0145, then add the two amounts together.

- Subtract the result of Step 2 from the individual's net Schedule C income or S corporation wages.

The steps for calculating the maximum contribution to a solo 401(k) plan are laid out in the "Deduction Worksheet for the Self-Employed" in IRS Publication 560.

For the employee part of the contribution, the individual can contribute up to 100% of their net compensation (the amount calculated in Step 3 above) or $20,500, whichever is less.

Figuring the employer’s allowed contribution amount requires one additional calculation: the plan’s maximum contribution rate (25%) must be reduced to account for the contribution itself, which is done by dividing the rate (as a percentage) by one plus itself. In effect, then, even though the ‘maximum’ employer contribution rate is 25%, the real maximum rate is 25% ÷ (100% + 25%) = 20%.

Finally, the employer portion of the contribution is also limited to the lesser of (1) the maximum allowed contribution as calculated above; (2) the difference between maximum combined limit ($61,000 for 2022) and the amount of the employee contribution; or (3) 50% of the difference between net compensation and the employee contribution.

Example 1: Larry Little is the owner and sole employee of Little Larry’s Locksmithing. Larry earns $100,000 per year in net income from his business, and he establishes a solo 401(k) plan in his business’ name to save for retirement.

To determine how much Larry can contribute to his solo 401(k) plan this year, it’s first necessary to calculate his compensation, i.e., his net earnings from self-employment. Following the three-step calculation above,

- Larry's earnings subject to self-employment tax are $100,00 × 0.9235 = $92,350

- One-half of the self-employment tax equals $92,350 × 0.0765 = $7,065

- Net compensation equals Larry's net schedule C income minus one-half of the self-employment tax, or $100,000 – $7,065 = $92,935.

Now it’s possible to calculate the separate employer and employee contribution limits for Larry’s solo 401(k) plan, which combined will give the maximum amount that he can contribute to his plan overall.

Employee contribution: The lesser of $20,500 or 100% of compensation (which is $92,935, as calculated above). $20,500 is the smaller number, so that is the maximum employee contribution.

Employer contribution: Up to 25% of compensation, adjusted for the contribution itself. The maximum allowed employer contribution is 0.25 ÷ (1 + 0.25) × $92,935 = $18,587.

The difference between the maximum combined limit and the amount of the employee contribution is $61,000 – $20,500 = $40,500

50% of the difference between net compensation and the employee contribution is 0.5 × ($92,935 - $20,500) = $36,217.50

The maximum employee contribution is the lesser of these three totals, which is $18,587.

Total contribution: The lesser of $61,000 or the sum of the employee and employer contributions ($20,500 + $18,587 = $39,087). $39,087 is the smaller number, so that is Larry’s maximum allowed total contribution.

As with other types of 401(k) plans, the employer portion of a solo 401(k) plan contribution is always pre-tax – that is, it is excluded from the participant’s gross income. However, the employee portion can be directed into either a pre-tax (traditional) account or a Roth account. The employee contribution can be either entirely pre-tax or entirely Roth, or a combination of both, as long as the total combined pre-tax and Roth employee contributions don’t exceed the employee contribution limit of $20,500 or 100% of compensation, whichever is smaller.

In addition to the ‘standard’ employee and employer contributions, there is a third layer of contribution possible for solo 401(k) plans: nondeductible employee contributions. Unlike traditional and Roth contributions, nondeductible contributions have both a pre-tax and an after-tax component: While the contribution itself is included in the participant’s gross income and can be withdrawn tax-free, any subsequent growth on the account is tax-deferred and is taxed upon withdrawal.

Why would someone want to make nondeductible contributions to a solo 401(k) plan? First, nondeductible contributions aren’t subject to the $20,500 limit for pre-tax and Roth employee contributions; rather, they can be made all the way up to the limit for all combined contributions, i.e., the lesser of 100% of compensation or $61,000. Which means that participants can use nondeductible contributions to max out their total contributions when they would otherwise be limited by the standard employee and employer contribution limits.

Example 2: Larry, from Example 1 above, wants to maximize his solo 401(k) plan contributions with after-tax funds.

Larry has already made a contribution of $20,500 (as employee) + $18,587 (as employer) = $39,087.

Because he can contribute up to a total of $61,000, Larry makes a nondeductible contribution of $61,000 – $39,087 = $21,913.

A second upshot of making nondeductible contributions to a solo 401(k) plan is that participants can convert the after-tax portion of the contribution into a Roth account while rolling any pre-tax dollars into a traditional account – i.e., the “Mega Backdoor Roth” strategy that the IRS has allowed since 2014. In effect, then, nondeductible contributions allow participants to make an additional Roth contribution on top of what is normally allowed using just the ‘standard’ employee contribution.

Example 3: Imagine that Larry, from the examples above, wants to make the maximum contribution to his solo 401(k) plan entirely in the form of Roth contributions.

Larry can first make the maximum standard employee contribution of $20,500, electing to contribute those funds to a designated Roth account.

Then, Larry can make the remainder of his maximum combined contribution, or $61,000 – $20,500 = $40,500, in the form of a nondeductible employee contribution.

Finally, Larry can convert the after-tax funds into a Roth account by rolling them into his designated Roth account. He has now effectively made a $61,000 Roth contribution to his solo 401(k).

Note: While Larry could also simply make $61,000 in after-tax contributions and then convert the entire contribution into a Roth account rather than making both an after-tax and a standard Roth contribution. However, if the value of the after-tax account grows at all in between the contribution and the conversion, that growth (which would be treated as pre-tax) would be split off into the pre-tax portion of the account. If part of the contribution were instead made directly into the Roth account, then any growth of those funds would simply retain their tax-free Roth treatment, reducing the potential for growth of contributed after-tax funds from being re-categorized as pre-tax funds prior to conversion.

Advantages Of Solo 401(k) Plans

Solo 401(k) plans have several features that make them stand out from other types of self-employed retirement plans, like Simplified Employee Pension (SEP) plans or SIMPLE IRAs.

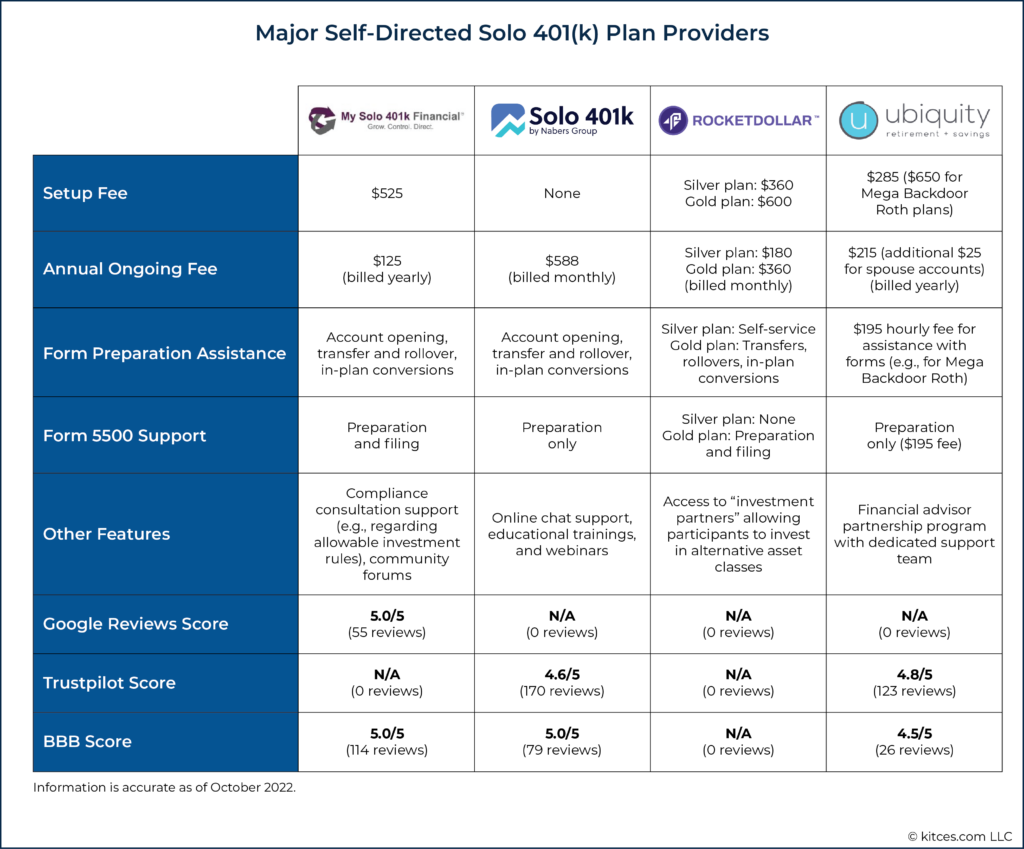

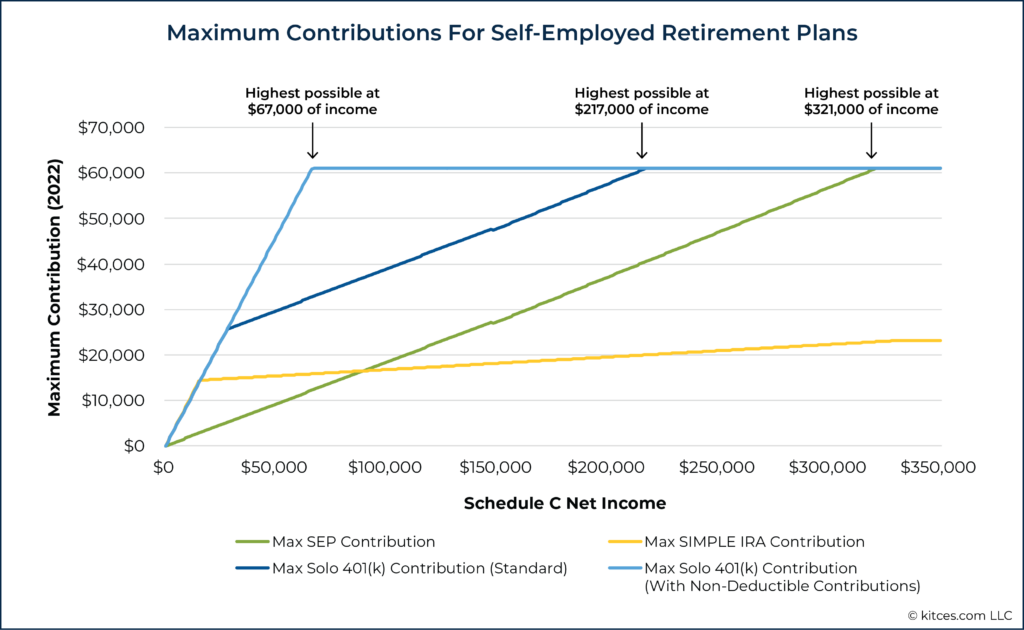

First is the ability to contribute a higher percentage of one’s income to the plan. While all workers, regardless of the type of employer retirement plan, are generally limited to a total of $61,000 (in 2022) in combined employee and employer contributions; the amount of income an individual must earn to be able to reach that maximum contribution limit changes based on the type of plan.

For example, SEP contributions are capped at 20% of the participant’s net self-employment income. This is effectively the same as the employer portion of the solo 401(k) plan contribution, but the additional employee portion allowed by the solo 401(k) plan – which can be 100% of compensation up to $20,500 – means that solo 401(k) plan participants can contribute a much higher percentage of their income if they don’t earn enough to max out the employee portion alone.

Specifically, in order to contribute the maximum of $61,000 to their plan, a SEP participant must earn $321,000 in self-employment income – whereas a solo 401(k) plan participant need only earn $217,000 to contribute that amount using standard employee and employer contributions, or just $67,000 when using nondeductible contributions, as shown below.

SIMPLE IRAs work similarly to solo 401(k) plans in that they also have an employee and employer component to the contribution, but both SIMPLE IRA portions have lower limits than those of solo 401(k) plans. For SIMPLE IRAs, the employee portion is limited to $14,000 in 2022 (versus $20,500 for solo 401(k) plans), while the employer contribution is capped at 3% of net self-employment income (versus 20% for solo 401(k) plans). For SIMPLE IRAs, the contribution limits lag behind solo 401(k) plans at incomes above $14,000 and behind SEPs at above $90,000.

One of the best use cases for a solo 401(k) plan, then, is for an individual who wants to save at a (potentially much) higher rate than a SEP or SIMPLE IRA would allow for their income level.

Another advantage of solo 401(k) plans is the ability to include a designated Roth account feature, allowing the plan participant to make both pre-tax and Roth contributions (keeping each type of contribution separate within the plan). As described above, solo 401(k) plan participants can allocate part (or all) of the employee portion of their contribution to a Roth account (the employee portion must remain pre-tax, no matter what). The upshot is that – like employees of larger companies whose 401(k) plans include a Roth option – solo 401(k) plan owners can make up to $20,500 in designated Roth contributions, with no income limits.

Other retirement plans for self-employed workers (like SEPs and SIMPLE plans) don’t allow Roth account features, and contributions made to a separate standard Roth IRA are capped at $6,000 per year (and are subject to a phaseout for higher income levels). In contrast, solo 401(k) plan participants can make standard employee contributions of up to $20,500 to a designated Roth account (as illustrated above); while by using nondeductible contributions in combination with the Mega-Backdoor Roth strategy, they can effectively contribute up to $61,000 to Roth per year. In other words, solo 401(k) plans are the only option for self-employed individuals who are set on making Roth contributions at higher levels (and potentially much higher levels) than a Roth IRA would allow.

Nerd Note:

The ability to maximize Roth contributions with a solo 401(k) plan might be particularly useful for individuals who want to avoid the adverse effects of pre-tax retirement savings on the Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction for business owners. Because the amount of QBI on which the deduction is based is reduced by the amount of any pre-tax contributions to the business’ retirement plan, the deduction for a self-employed taxpayer – generally calculated as 20% of QBI – is reduced any time they make a pre-tax contribution to a SEP, SIMPLE, or solo 401(k) plan. This effectively reduces the tax-deductibility of ‘pre-tax’ contributions while the QBI rules are in effect through 2025, meaning that plans that offer Roth contribution options – such as solo 401(k) plans – may offer more tax benefits than those that only allow pre-tax contributions.

The Unique Challenges Of Setting Up And Managing Solo 401(k) Plans

While solo 401(k) plans can offer higher contribution potential and increased flexibility to make Roth or after-tax contributions, the flip side is that they can also come with greater administrative complexity to implement and maintain than other types of retirement plans.

This is because, in the eyes of the IRS, solo 401(k) plans are the exact same type of entity as the ‘standard’ 401(k) plans offered by larger employers. And although they are exempt from the nondiscrimination testing that plans with multiple participants are subjected to, solo 401(k) plans are still required to follow IRS rules regarding the establishment and administration of qualified retirement plans as summarized in IRS Publication 560. These requirements include:

- The adoption of a written plan document;

- Filing Form 5500-EZ when plan assets exceed $250,000; and

- Meeting the required deadlines for establishing and contributing to the plan.

It’s worth going into more detail on the above to better understand the requirements for solo 401(k) plan owners and what elements of the plan they must either manage themselves or outsource to a third party.

Nerd Note:

Although solo 401(k) plans are subject to most of the IRS regulations regarding qualified plans, they are not subject to the requirements for employer retirement plans under ERISA – meaning that planners who advise clients on solo 401(k) plans do not need to decide whether to act as a 3(21) or 3(38) fiduciary as they would when advising on 401(k) plans for businesses with more employees; they can simply advise the business owner as they would on their other personal investments.

However, if the business were to ever hire additional employees (other than the owner’s spouse), the solo 401(k) plan would convert to a multi-employee 401(k) plan and the ERISA requirements would kick in. It’s crucial for advisors to understand the intentions of their business owner clients – in particular, whether (or when) they intend to hire employees – before setting up the solo 401(k) plan to plan for the impact of hiring employees on the business’s retirement plan.

The Written Plan Document

In a nutshell, the plan document for a solo 401(k) plan (and for bigger employers’ 401(k) plans, for that matter) is a broadly written description of the plan’s provisions, including who is eligible to participate; how the plan handles contributions, distributions, and loans; and rules for vesting and forfeiture of participants’ assets.

The main purpose of the plan document is to ensure that the plan complies with IRS and/or ERISA rules wherever applicable. Plan documents tend to be written by solo 401(k) plan providers in generic legal boilerplate so as to apply to as many different individual plans as possible; however, they often aren’t that useful at communicating practical information about the plan itself. Much of the language used in the plan document is broad and nonspecific, so determining how the plan actually works in practice can be difficult to determine from the plan document alone. For example, a plan document might state that the plan “may allow” participants to make Roth contributions or take out loans from the plan (because the IRS says that qualified plans may allow these features), when in reality the plan itself may not actually allow Roth contributions or participant loans. So when setting up a new solo 401(k) plan or reviewing an existing plan, the plan document itself won’t necessarily be the most useful source for finding out the plan’s specific features.

The place where those features can be found is typically in the plan’s Adoption Agreement, a shorter form that typically accompanies the plan document. Numerous key features of the plan are outlined in the Adoption Agreement, including:

- The plan’s effective date;

- Age and service time requirements for participants (though obviously self-employed individuals aren’t likely to place any restrictions on their eligibility to participate in their own retirement plan);

- Types of contributions allowed (e.g., employer and employee contributions; and Roth and/or nondeductible deferrals for employees);

- Allowability of participant loans from the plan.

Form 5500-EZ

All solo 401(k) plans with assets over $250,000 as of the end of the plan year are required to file Form 5500-EZ with the IRS and Department of Labor by the last day of the seventh month of each plan year (usually July 31). The form includes basic information about the employer and plan administrator (who are usually the same person in a solo 401(k) plan), plan assets at the beginning and end of the year, and contributions and rollovers received during the year. The form can be filed electronically online via DOL’s EFAST2 system.

Although filing Form 5500-EZ is a relatively simple process, it is common to find business owners who have forgotten to file by the deadline. This can be a costly mistake: The IRS imposes a steep penalty of $250 for each day after the deadline that the form is filed, up to a maximum of $150,000. However, the IRS does offer some relief from this penalty for solo 401(k) plan owners, allowing those who have filed late to pay a flat fee of $500 per delinquent form (up to a maximum of $1,500 total).

Still, this is a hefty price to pay compared to the amount of time it takes to prepare and file Form 5500-EZ, so for advisors with clients who own solo 401(k) plans near or above the $250,000 filing threshold, sending out a reminder for those clients to prepare and file the form in late spring or early summer could be a valuable nudge.

Plan Establishment And Contribution Deadlines

Solo 401(k) plans must be established by December 31 of the first plan year for which they are effective. For example, in order to make contributions to a solo 401(k) plan for 2022, the plan must be established by December 31, 2022.

The contributions themselves, however, don’t need to be made until the individual tax filing deadline of April 15, or October 15 with a six-month extension.

The Two Approaches To Setting Up And Managing A Solo 401(k) Plan

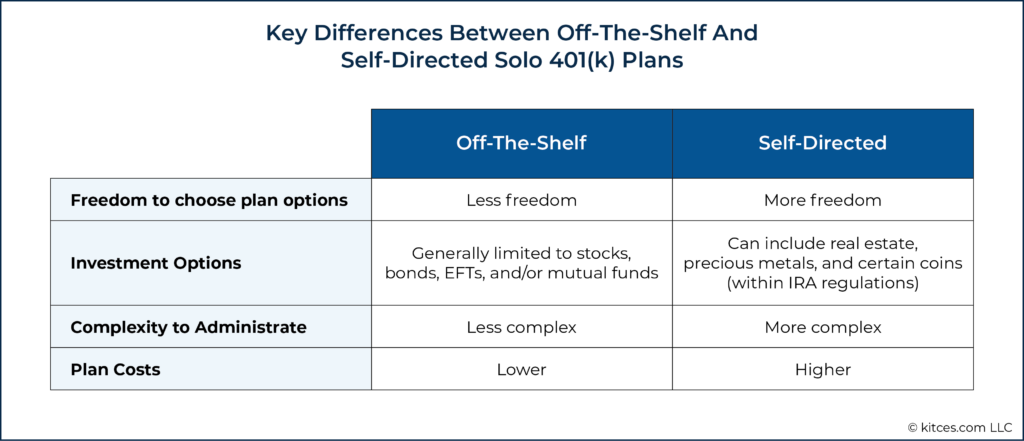

Solo 401(k) plan participants usually don’t write their own plan documents – they rely on third parties to draft template documents to ensure they comply with applicable laws and regulations. Generally, there are two ways that participants go about obtaining and adopting plan documents: They use a pre-written set of documents provided by a financial institution (which could be called the ‘off-the-shelf’ approach), or they hire a third-party provider to write the documents to their specifications (i.e., the ‘self-directed’ approach). Understanding the mechanics and potential benefits and drawbacks of each approach can help individuals better select a plan that meets their needs.

The ‘Off-The-Shelf’ Approach

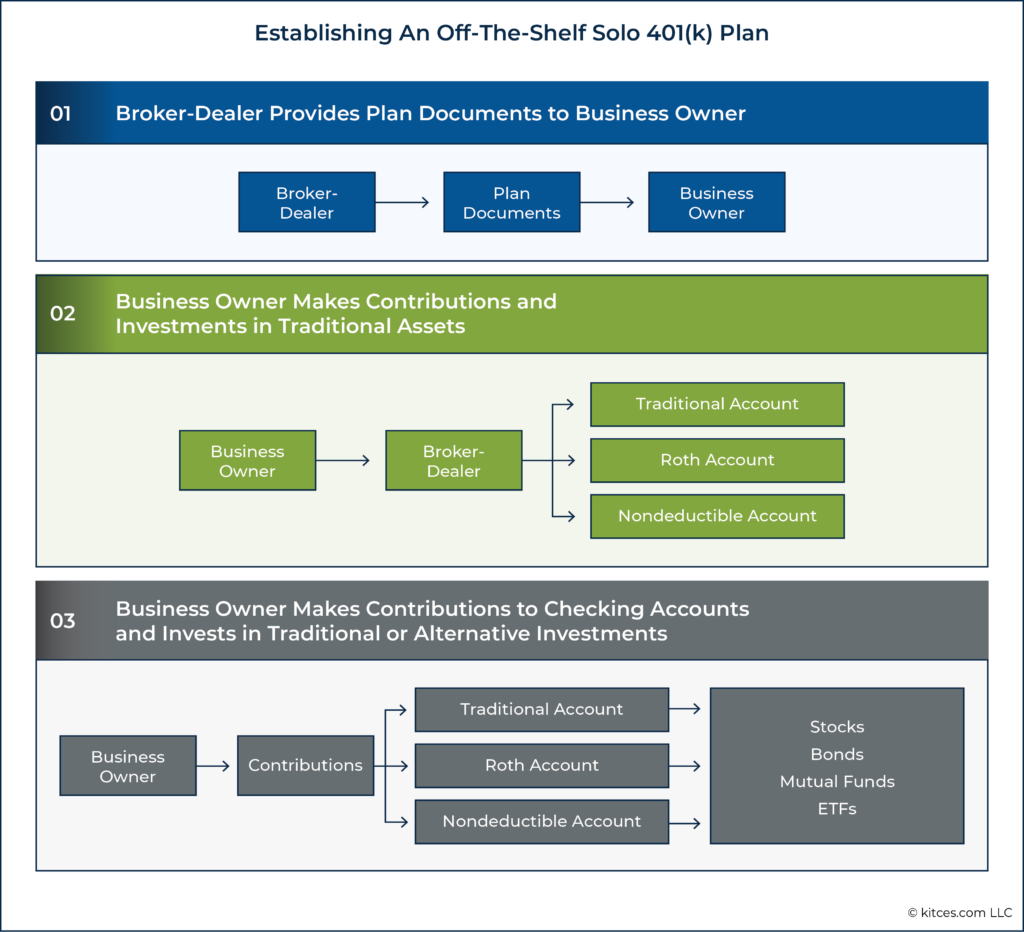

With the off-the-shelf approach, the individual goes to a financial institution (such as a broker-dealer), which provides a pre-written and IRS-approved solo 401(k) plan document along with an adoption agreement. The business owner fills these forms out and signs them to establish the plan. The individual signs another form naming the financial institution as the custodian of the plan (more on this later), then opens an account at the institution, funds their contributions, and invests the assets.

Off-The-Shelf Solo 401(k) Plans

If someone wanted a solo 401(k) plan that required little more effort than going to the grocery store and picking a box of cereal off the shelf, this is the type of plan they would choose. It has the convenience of working with a single vendor who handles all of the plan's design decisions, saving the individual some of the mental load that comes with more customized plans.

Also, because the financial institutions providing the plans are generally earning revenue from them in other ways – e.g., by the client investing in the company’s mutual funds, or by earning income from trading commissions, payment for order flow, or the spread on cash deposits from the client’s account – there tend to be few direct costs to the business owner for setting up and administering these types of plans.

However, the benefits of convenience and low (direct) fees that off-the-shelf plans offer can come with a downside in the form of an inability for participants to customize their plans for their own needs. Financial institutions streamline their plan administration capabilities as much as possible to be able to offer them at scale, and so they tend to be fairly rigid about the features of the plans that they offer. As a result, some institutions don’t allow options such as Roth or after-tax contributions that business owners may want to have in their solo 401(k) plans.

Nerd Note:

A timely example of the rigidity of off-the-shelf solo 401(k) plans comes from the ongoing integration of TD Ameritrade into Charles Schwab following Schwab’s 2020 acquisition of TD Ameritrade. While TD Ameritrade’s off-the-shelf solo 401(k) plan included the option to make Roth contributions, Schwab’s does not – and in December 2021, Schwab began notifying advisors on the TD Ameritrade custodial platform that they would be removing the Roth option in 2022, forcing plan participants and advisors to decide whether to stay in their current plans without the Roth option or seek out alternatives.

For advisors on the TD Ameritrade platform who are affected by Schwab’s decision, the ‘Self-Directed Approach’, discussed below, might be of interest since it offers a way to custody assets with TD Ameritrade (and eventually Schwab) but continues to offer a Roth solo 401(k) option.

With the off-the-shelf approach, the business owner (or often in practice, the advisor they work with) generally handles the administrative aspects of maintaining their solo 401(k) plan. The custodian may provide tax forms like 1099-Rs for plan distributions and rollovers, but the participant is responsible for other actions like determining the amount of their contribution and filing Form 5500-EZ (for plans with assets over $250,000).

The key takeaway from the off-the-shelf approach is that it can provide some upfront convenience and cost savings when setting up the plan – however, the participant is generally stuck with whatever boilerplate options the financial institution decides to provide, and on an ongoing basis, the participant is on the hook for most administrative tasks required to maintain the plan and stay compliant with IRS regulations.

The ‘Self-Directed’ Approach

Instead of opting for the less flexible off-the-shelf approach, a self-employed individual may want to create a more customized set of solo 401(k) plan documents with features tailored specifically to that individual’s desires. In addition to having more flexibility than an off-the-shelf plan on options like Roth features, after-tax contributions, and plan loans, this approach may also allow an individual to use their solo 401(k) plan to invest in alternative assets that many off-the-shelf providers don’t allow, like real estate, hard assets (e.g., gold and silver), and cryptocurrency.

Most significantly, however, a self-directed solo 401(k) plan gives the business owner the most control over how their plan is managed over time, since it isn’t at the discretion of an off-the-shelf provider that can change aspects of the plan at their own whims.

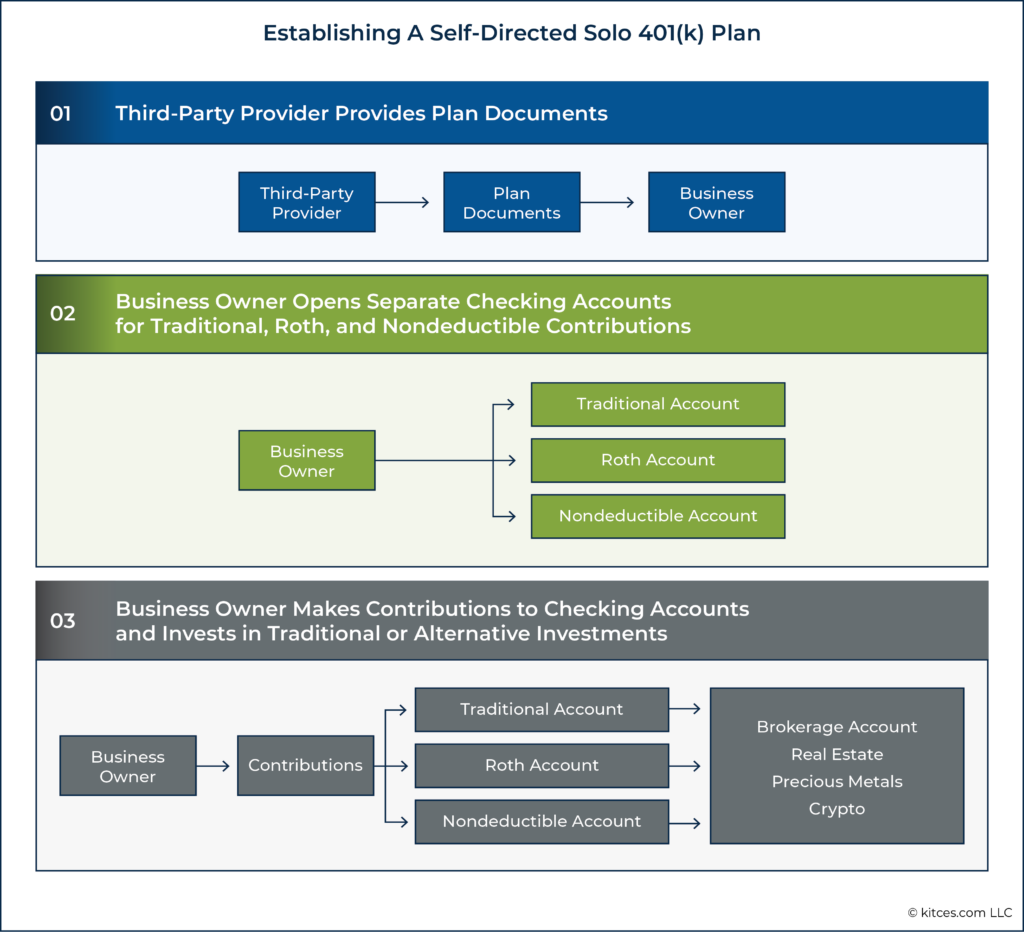

When implementing a self-directed solo 401(k) plan, an individual would typically hire a third-party self-directed solo 401(k) plan provider, who would handle the creation of the plan document and adoption agreement. The provider may also take on additional duties for the ongoing management of the plan, like keeping records of contributions and withdrawals, preparing and filing Form 5500-EZ annually (when plan assets exceed $250,000), and facilitating transactions like Roth conversions and rollovers. However, there is no single defined set of duties for a solo 401(k) plan provider, so it’s important to understand which duties are the responsibility of the provider and which are the responsibility of the business owner.

Compared to the off-the-shelf approach, which tends to be centered around the financial institution that provides the plan documents and takes custody of the plan assets, the self-directed approach is often more decentralized. Individuals can open checking accounts in the name of the plan (or more accurately, in the name of a trust on behalf of the plan), which are then used to fund brokerage accounts for traditional investments, purchases of real estate or alternative investments, or crypto exchange accounts for crypto assets. Rather than relying on a single custodian for plan assets, the business owner can choose where to hold and invest their funds.

Notably, when a business owner chooses a self-directed 401(k) plan, they are responsible for keeping traditional, Roth, and after-tax assets separate from each other. This typically involves opening separate accounts for each type, and not commingling funds for purchases of assets such as real estate.

Self-Directed Solo 401(k) Plans

The upshot here is that, even for individuals who aren’t planning to invest in any alternative assets, a self-directed solo 401(k) plan might be attractive because it can allow the participant to hold their plan’s investments at the traditional broker-dealer of their choice (like Schwab or Fidelity), with more flexibility of plan features than using one of those broker-dealers' off-the-shelf plans.

For example, even though Schwab’s off-the-shelf 401(k) plan doesn’t allow Roth contributions, a solo 401(k) plan owner can establish a self-directed solo 401(k) plan that does allow Roth contributions, then open a Schwab trust brokerage account in the plan’s name to invest the plan’s funds in (with instructions for the custodian to treat the accounts as tax-free, which is done when filling out the account opening paperwork, so they do not report any dividends, interest, or capital gains generated in the account to the IRS). The only difference between this approach and an off-the-shelf plan is that, with the off-the-shelf plan, Schwab would provide the plan documents and provide (limited) administrative support and recordkeeping, while with the self-directed plan, Schwab would provide only the trust account(s), and the business owner would need to handle the rest on their own (or hire a third party to do so).

Because there is more flexibility in how the assets in a self-directed solo 401(k) plan are invested, participants must also take care not to run afoul of the prohibited transaction rules stated in IRC Section 4975, which forbid plan assets from being used in a way that benefits the plan’s owner (or their spouse or relatives). This means that, for example, a solo 401(k) plan owner can’t purchase a house using their plan’s funds and then move into it themselves, nor can they rent it out to themselves or their family. Such transactions are subject to a penalty tax of 15% of the amount involved (although unlike the similar rules for prohibited transactions within an IRA, engaging in a prohibited transaction within a solo 401(k) plan doesn’t cause the entire account to lose its tax-deferred status).

Additionally, self-directed solo 401(k) plans cannot invest in life insurance contracts, nor can they invest in “collectibles” as defined by IRC Section 408(m), which include artwork, antiques, wine, and other physical property, save for certain coins and precious metals if they are held by a bank or other approved trustee. Purchasing these assets with plan funds is treated as a distribution from the plan, and is subject to any accompanying taxes and penalties.

Because of the addition of a third party to the mix, the possibility of holding investments in multiple locations rather than a single custodian, and the need to be aware of the rules for prohibited transactions and disallowed assets, self-directed solo 401(k) plans naturally come with more complexity than off-the-shelf plans.

The self-directed approach may involve more costs than off-the-shelf plans as well: Plan providers often charge several hundred dollars for the initial plan setup and annual plan maintenance fees (which can generally be deducted as business expenses on Schedule C or Form 1120S).

There is an additional cost in time and hassle, however, since compared to an off-the-shelf plan – where a broker-dealer handles the administration of the plan as well as providing the investment accounts, and also serves as a single point of contact for customer support service – a self-directed solo 401(k) plan may have multiple points of contact that require more time to track down the right source of information for a question. And when more than one of those contacts need to coordinate with each other to provide an answer, the time cost increases even more.

When choosing between an off-the-shelf solo 401(k) plan and a self-directed plan, then, the biggest issues to consider (in order of importance) are:

- Which types of option(s) are needed (e.g., Roth or after-tax contributions, allowance of participant loans, ability to choose investment options);

- How much simplicity or complexity is desired (e.g., is it more important to have a single point of contact for all things relating to the plan, or is adding a third-party administrator acceptable?); and

- What fees and other costs are involved (e.g., if multiple options fit the needs for a plan based on options #1 and #2, which will do so for the lowest total cost?).

Choosing A Solo 401(k) Plan Provider

After deciding whether to use an off-the-shelf or self-directed solo 401(k) plan, the next step is choosing a plan provider.

Most major broker-dealers offer an off-the-shelf solo 401(k) plan option, including those broker-dealers who serve as custodians for many financial advisors. In that light, what might seem simplest would be to use the off-the-shelf plan offered by the custodian where the advisor’s other clients are already located.

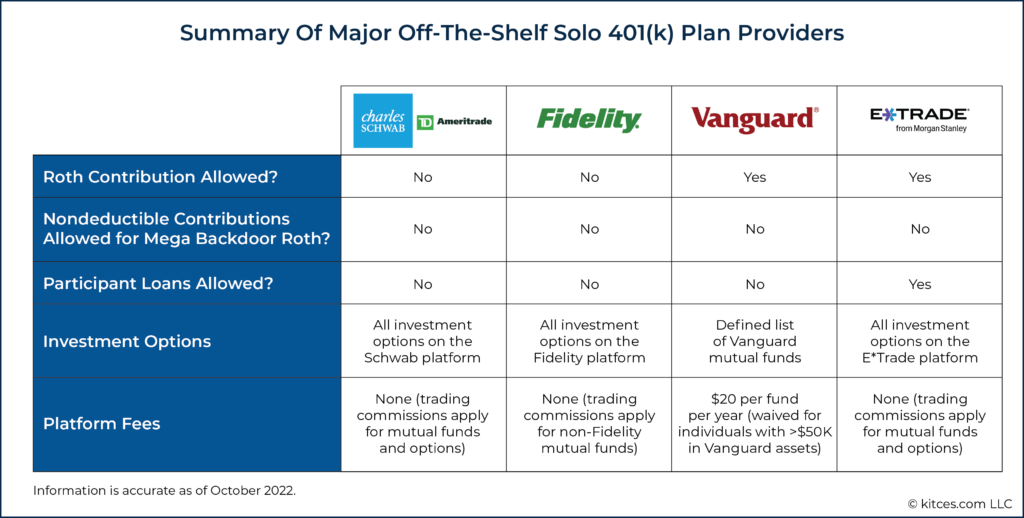

However, the plan's features offered by the biggest broker-dealers might leave a lot to be desired. None of the ‘Big Three’ of Charles Schwab, TD Ameritrade (which merged its off-the-shelf solo 401(k) plan with Schwab’s earlier in 2022 in preparation for the two companies’ merger), or Fidelity offers the option to make Roth contributions, nondeductible contributions, or the ability for participants to take out loans.

Among other options, Vanguard does offer the ability to make Roth contributions, but they do not allow nondeductible contributions or participant loans. Additionally, while other off-the-shelf providers generally allow solo 401(k) plan participants to invest in anything that would normally be available on that broker-dealer’s platform (e.g., individual stocks, bonds, and options, as well as ETFs and mutual funds from any provider available on the platform), the investment options in the Vanguard plan are restricted to only a pre-selected list of Vanguard mutual funds. Which may seem fine for a solo 401(k) plan participant who only wants to invest in Vanguard mutual funds anyway, except there is also a $20 per year fee for each Vanguard mutual fund held in a Vanguard solo 401(k) plan (for accounts under $50,000) – which means that, ironically, it could be less expensive to use any of the providers other than Vanguard to invest in Vanguard mutual funds in a solo 401(k) plan.

Among the major off-the-shelf solo 401(k) plan providers, E*Trade appears to offer the most flexibility in plan options, being alone in offering the ability to make both Roth contributions and participant loans, and allowing participants to invest in any investment available on the E*Trade platform. Like the other providers, however, nondeductible contributions are not allowed in E*Trade solo 401(k) plans.

It’s also worth noting that, like TD Ameritrade, E*Trade has been acquired in recent years (merging with Morgan Stanley in 2020), and although there have been no announced plans to change any of the solo 401(k) options in light of the merger, the fact remains that the features of E*Trade’s off-the-shelf plan are subject to the preferences of its new corporate parent, and that a change wouldn’t be unheard of in light of the TD Ameritrade/Schwab situation.

Self-directed solo 401(k) plans, by definition, offer more flexibility than off-the-shelf options, meaning that they all offer the ability to make Roth and nondeductible contributions, allow participant loans, and let the participant invest in anything allowed by the IRS, including real estate, cryptocurrency, and precious metals.

The basic services of major self-directed plan providers generally include a set of initial plan documents pre-approved by the IRS, as well as any required updates or restatements of the plan (which are required to happen every 6 years by IRS regulations). They also usually provide paperwork and support for events like loans from the plan, distributions and rollovers, and plan splitting pursuant to a Qualified Domestic Relations Order (QDRO).

Choosing a self-directed plan provider, then, tends to come down to three main factors:

- The amount of support they offer in terms of assisting with paperwork, transactions, and tax filing;

- The quality and responsiveness of customer service; and

- The fees they charge.

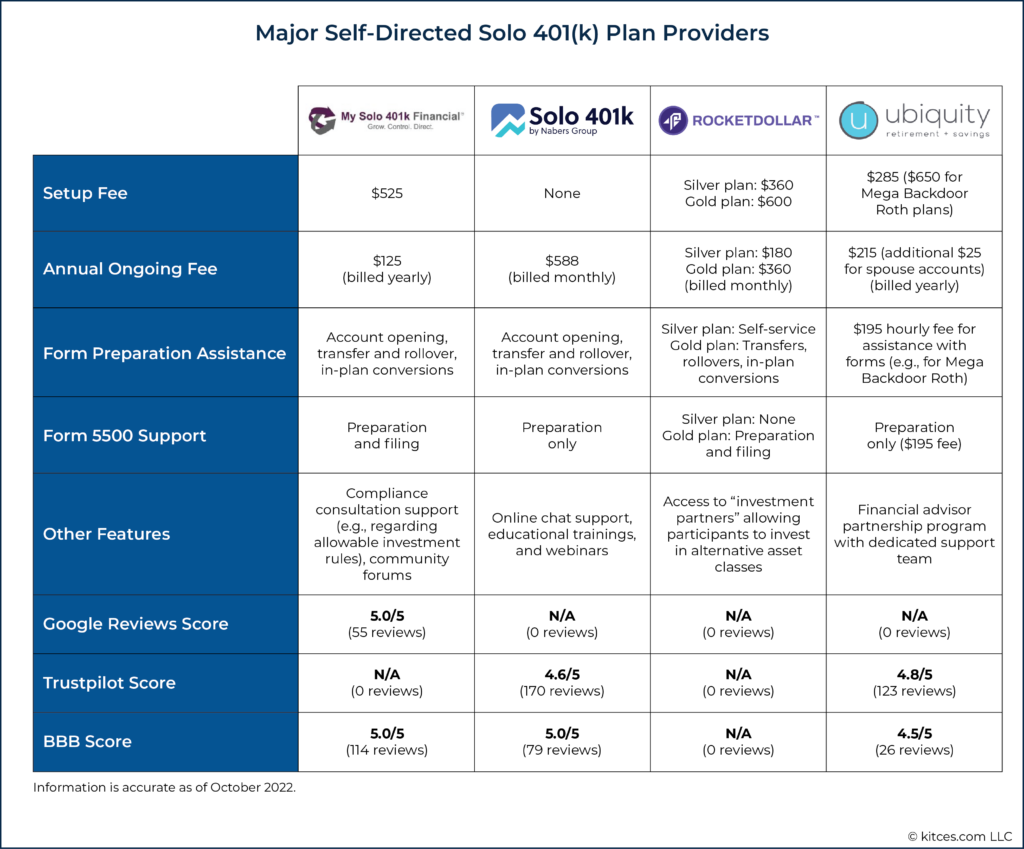

MySolo401k and Nabers Group are the two most experienced firms in the self-directed solo 401(K) space, with both dating to the early days of solo 401(k) plans in the late 2000s. Both are set up to provide full-service guidance through the process of establishing a plan, opening investment accounts, making contributions and rollovers, and reporting taxes. Rocket Dollar and Ubiquity are newer to the industry and more geared towards self-service, meaning individuals are more on their own in terms of opening accounts and filling out transaction paperwork (although Rocket Dollar does offer a “Gold”-tier plan with more full-service support, while Ubiquity charges a $195 hourly fee for support on account and tax paperwork).

Fees vary broadly across the options, although generally, providers with higher initial setup fees charge less on an ongoing basis. So while, for example, an individual enrolling in a Nabers Group plan would pay nothing upfront to set up (compared to other options whose startup fees range from $285-$650), they would pay more per year on an ongoing basis at $588 versus the other options that charge $125-$360 per year – which being an ongoing rate rather than a one-time setup fee, could make it significantly more expensive over the life of the plan.

Below is a summary of some of the major self-directed solo 401(k) plan providers and the features that they offer:

The key consideration as a financial advisor, then, is how involved the client (and the advisor themselves) desires to be in the process of setting up, funding, and administering the solo 401(k) plan. If the advisor is able to support the client on things like preparing account, transfer, and rollover forms as well as other administrative items like calculating and tracking contributions and knowing when and how to file Form 5500-EZ, there may not be as much need to enroll with one of the more expensive full-service options. In this sense, providing this support as an advisor represents a substantial value-add for the client, since it might save the client hundreds of dollars per year over multiple years (and possibly decades) on the more expensive solo 401(k) plan providers.

Although solo 401(k) plans can be somewhat more complex to manage than other types of investments, the value they provide in the flexibility of features and the ability to build up tax-advantaged savings can make them more than worth the effort required to set up and manage.

This combination – high value and high complexity – is the type of situation where financial advisors can thrive. Helping self-employed clients navigate the broad landscape and potential pitfalls of establishing and managing a solo 401(k) plan, delivering plans to those clients with the features they need, and working to maximize the plan’s benefits each year, is the perfect example of the type of value that clients can see on an ongoing basis.

I don’t believe I saw this addressed, andI apologized if I missed it. I recently came across a business owner who is 50/50 partners with his brother. They have no other employees. After doing some digging, I believe that in a circumstance like this, where there are multiple owners and no other employees, the business owners can establish their own individual/solo 401(k)s. I would love to confirm whether or not there are any issues with this. Has anyone come across any good articles that address multiple owner businesses and establishing solo 401(k)s?

In a situation like this, the business establishes a 401k and both brothers are eligible to participate in it. It is not technically a “solo 401k”, but the flexibility afforded to solo 401ks (including the ability to make Mega-Backdoor Roth contributions by converting After-Tax contributions to Roth) will functionally be in effect. Since there are no “Non-Highly Compensated Employees” by the IRS’ definition, the plan will automatically pass all relevant non-discrimination tests that would typically hamper an owner’s ability to contribute.

The key is to work with a competent TPA to draft the plan document appropriately to include all the language that allows for your desired plan design features – such as After-Tax contributions, in-plan Roth conversions, loans, etc. The TPA shouldn’t care who you use as a custodian either, if they’re just in the business of TPA work. I’ve found a local TPA that I utilize for solo 401k plans.

How to handle this case: a client has two separate sources of income, one with an employer w a established 401k plan where contributions are maxed out (20k), and another separate LLC business w a SEP IRA. Assuming separate LLC income of $250, $60k (24% of adj income) potential SEP contribution, does the employer 401k contribution net against the $60k SEP max contribution making the max allowable pre tax contribution into SEP $40k?

Hi Brian – when a person has multiple employers, their elective deferrals (i.e., employee contributions) net against each other across all plans, but their annual addition limit (the total amount they can contribute) is a per plan limit.

So the amount that a person contributes as elective deferrals to one employer’s plan does NOT reduce the amount they can contribute, in total, to a different plan. In the case you described, the individual could contribute the full maximum amount to their SEP while still maxing out their elective deferrals in their other employer’s 401(k) plan.

Ben, I have a praise and a criticism for you. First the praise.

I really (Really!) liked the extra effort you put into providing specifics about who were the major plan custodians for solo 401(k)’s, along with their advantages and drawbacks. This information will save me a lot of time on those occasions when I am asked about this topic.

Now the criticism.

I very seldom encounter a Kitces.com article that has the tax facts incorrect. But your “Larry Example 1” is such a case. When calculating the maximum Employee contribution to the solo 401(k), the Employer contribution must be calculated first (not second as in your Larry example). Then the Employee’s Compensation is correctly calculated as their Net Profit (or loss) from Schedule C, minus 1/2 of their Self-Employment tax, minus the Employer contribution to the solo 401(k). It is the “circularity” of the calculation for the maximum Employer contribution that necessitates the “trick” with the fractions.

Anyone interested in this tax calculation should consult a good taxation reference book. The IRS has also posted a worked-out example on their https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/self-employed-individuals-calculating-your-own-retirement-plan-contribution-and-deduction webpage.

You are correct. However, this would only be relevant if the combined employer and employee contributions exceeded the individual’s net compensation. As long as you are checking to make sure you haven’t violated this contribution limit, you will be ok.

Ben had already noted earlier that total plan contributions can’t exceed net compensation. My guess is, he simply skipped the step of comparing total employer/employee contributions against net compensation in Larry Example 1 because he had already mentioned this limit.

@artprunier:disqus thank you for the praise and for your check of my work!

However, I don’t think the calculation works quite how you’ve described it. The employer contribution does require reducing net compensation by the amount of the contribution itself, hence the adjustment of the contribution rate (0.25 / (1+0.25) = 0.2).

However, the employee contribution doesn’t require any such adjustment. In fact, it is the employer contribution that depends on the amount of the employee contribution: The employer deduction is limited to the lesser of (1) net compensation times the adjusted contribution rate; (2) the maximum combined contribution limit ($61,000 in 2022) minus the amount of the employee contribution; or (3) 50% of the difference between net compensation and the employee contribution.

This is laid out in IRS Publication 560, in the section titled “Deduction Worksheet for the Self-Employed”.

I left some of the details of the above calculation out of the original example above, but I’ve added them in for clarification.

Hi Ben,

I thought this was a very informative article and is helpful to have so much information on solo 401ks in one place. I was wondering if you would be able to expand on the plan establishment deadline. I’ve read other articles that state if you establish the plan by 12/31 you can make employee and employer contributions for that year. But if you wait to establish it after 12/31 (and before tax filing deadline) you can only contribute the employer portion of contributions. I would appreciate any clarity you can provide.

Thank you,

Jennie

Hello,

Thank you for the thoughtful article.

Isnt the calculation of the employer contribution for a solo 401k for an S Corp far more simpler? The example 1 above mentions S Corp and makes it more complicated.

Isn’t it correct? S Corp gives W2 wages to the owner/employee, say $100K.

As an employee, he contributes 20,500 to his solo 401k

As an employer, the S Corp contributes 25% of W2 wages (100K), 25,000 to his solo 401k

Ref: https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/one-participant-401k-plans

Example: Ben, age 51, earned $50,000 in W-2 wages from his S Corporation in 2020. He deferred $19,500 in regular elective deferrals plus $6,500 in catch-up contributions to the 401(k) plan. His business contributed 25% of his compensation to the plan, $12,500. Total contributions to the plan for 2020 were $38,500. This is the maximum that can be contributed to the plan for Ben for 2019.

Did I misunderstand? Please help clarify.

Thank you

Vinay

Great Article. I have a Solo 40lk with North Western Mutual and they are not telling me that they do not have a plan document. That I have to hire a TPA for that and they only do financial advising. I am confused because I would have thought they would have had to set up the plan in order to do the investing.

Very informative – thank you! MySolo401k set up my original plan a few years ago, but now they’re billing me for an annual fee although they don’t provide any services to me. They state the following: “In order to have and continue to have an IRS approved solo 401k an IRS approved plan provider like My Solo 401k Financial provider is required.” Is this true? Can I not continue my role as the plan administrator and avoid these costs? I’ve done extensive reading on IRS.gov and haven’t found this requirement.

thanks!

excellent Thank you so much!

Thanks so much for this article. I’m on my third read and it’s the furthest I’ve gotten with anything so far in understanding the ins and outs. I do have a question about this part, though, and I’d be grateful for your insight:

“Larry could also simply make $61,000 in after-tax contributions and then convert the entire contribution into a Roth account rather than making both an after-tax and a standard Roth contribution. However, if the value of the [nondeductible?] after-tax account grows at all in between the contribution and the conversion, that growth (which would be treated as pre-tax) would be split off into the pre-tax portion of the account. [[If part of the contribution were instead made directly into the Roth account, then any growth of those funds would simply retain their tax-free Roth treatment, reducing the potential for growth of contributed after-tax funds from being re-categorized as pre-tax funds prior to conversion.]]

The part in double brackets is what’s not getting through to me; why does splitting the contributions prevent growth on the nondeductible portion between the contribution and the conversion (and therefore needing to be recategorized)? Why is it that we don’t want the splitting off and recategorization to occur? And, perhaps, does “If part of the contribution” refer to the $20,500 employee contribution, or some other number?

Thanks for reading—wish I could explain my confusion better, but I guess the whole thing just isn’t clicking ‘:)